John Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy goes out laughing at a world done in not with slimy abominations or bad paperbacks, but a collective shrug at reality.

I can’t recommend you watch In The Mouth Of Madness. I’m about to spend over a thousand words on why it’s great in ways I used to take for granted, including its condemnation of that very same sin, taking things for granted. I’ll probably award it a rare five out of five by the time I get to the bottom. But I still don’t think I would actively, personally suggest you stream it right now.

Because it scared the shit out of me.

I first watched In The Mouth Of Madness during an early teenage mania. I’m not sure which Carpenter movie did it— late-night glimpses of Halloween on AMC were already a formative trauma — but I had finally discovered him and I was insatiable. I tore through every DVD I could reserve from the library and every VHS tape I could scrounge from yard sales.

Somewhere in between Memoirs of an Invisible Man and They Live, I found In The Mouth Of Madness.

It was okay. I was then, as I am now, a Sam Neill acolyte. Seeing him work with Carpenter again after Memoirs, as a chain-smoking investigator no less, was the easiest possible sell. But it didn’t have the visceral chills of Halloween, or the Swiss-watch construction of The Thing, or even the pop-fizz satisfaction of Big Trouble in Little China. My squishy USC-aspiring brain recognized only the aspects of Basic Carpentry most easily translated into film school trivia.

I was missing the forest for how many trees him and Gary Kibbe could fit in the anamorphic frame.

I also had not seen Prince of Darkness — my county library system still doesn’t have a copy — but I count that as a retrospective grace.

I would’ve thought that it okay, too, if maybe better by an inch. That inch accounts for its contact-high Thing paranoia and the preternatural stillness that haunts so much of his earlier hits. But the devil sludge and the quantum physics and the zombie bums. It would’ve been all too…odd.

Had I known In The Mouth Of Madness was the end of an unofficial trilogy in Carpenter’s work, a trilogy I’d never seen the middle of, I might’ve watched it differently.

Watching it now, with near-intimate knowledge of the other two installments in the “Apocalypse Trilogy” and a slightly less squishy brain, Madness gnawed on deeper nerves than anything else in John Carpenter’s entire filmography.

The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In The Mouth Of Madness make a lumpy trilogy only because the first one is roundly considered one of the greatest horror films ever made. However, I’d argue that lumpiness, and what makes The Thing the thing, is inherent to the apocalyptic course charted among the three. They share a broad subject matter — the ooey, gooey End with a capital E — but each also runs with the last movie’s torch until it burns too dim to fight the encroaching darkness.

In The Thing, the anxious souls of U.S. Outpost 31 fight the unknown with logic. An autopsy. The hopeless computer calculation that you’ve recently seen on Twitter. A crude blood test. The ending may not be rainbows and cold beers, but the plan works — they figure out how the alien operates and give it no option but to die. Even if it’s alive in one of the survivors, it’ll still be immobilized until global warming picks up the pace.

In Prince of Darkness, the brave band of aspiring quantum physicists boil down the antichrist to points on a curve. It even starts talking in ones and zeros. Logic works, until it doesn’t. Until the unholy liquid moves in ways it shouldn’t and takes them over, one by one. Until a man dissolves in a pile of writhing insects before their very eyes. Until they start receiving transmissions from the future as repeating nightmares.

They win in the moment — the unknown stays that way — but the closing seconds assure that they didn’t stop the apocalypse so much as change its shape.

The opening credits of In The Mouth Of Madness show the sausage being made.

No blood, but plenty of gore; horror novels being printed by the pallet. Carpenter wanted Metallica’s “Enter Sandman.” We’re better off with the consolation prize, a split-difference with synth from Carpenter and a downright dirty riff from Kinks guitarist Dave Davies. It doesn’t even sound like it belongs to the rest of the score, but the whiplash works. The music gets enough blood pumping so you shiver when it drains in the first scene.

By the end of those credits, logic has already lost.

John Trent is a raving lunatic. He’s not all the way gone — he does feel bad about kicking an orderly in the balls — but he can see certainly see it from his padded cell. “I’m not insane!” he shouts, rallying the other patients in reverse-Spartacus solidarity as each pleads that they, too, are not insane. It forces the staff to bring out the heavy guns, an ice cream truck cover of “We’ve Only Just Begun.”

If nothing else, Trent still has taste: “Not The Carpenters, too.”

Then a shadow crosses his room, catches his eye, and calls up something lucid. Anger, pure and simple. “This is a rotten way to end it.” The shadow corrects him as calmly as the Germanic thunder of Jurgen Prochnow allows, “This is not the ending. You haven’t read it yet.”

H.P. Lovecraft was no stranger to the convenient elasticity of time.

More than a few of his stories are told in at least partial flashback or cautionary flash-forward. “The Dunwich Horror,” for instance, opens with a pastoral description of its setting and only off-handedly mentions how the townsfolk eventually bury the events to come:

“In our sensible age – since the Dunwich horror of 1928 was hushed up by those who had the town’s and the world’s welfare at heart – people shun it without knowing exactly why.”

There’s no discussing Madness without Lovecraft. It’s often considered the best adaptation of his work despite not actually adapting any of his work.

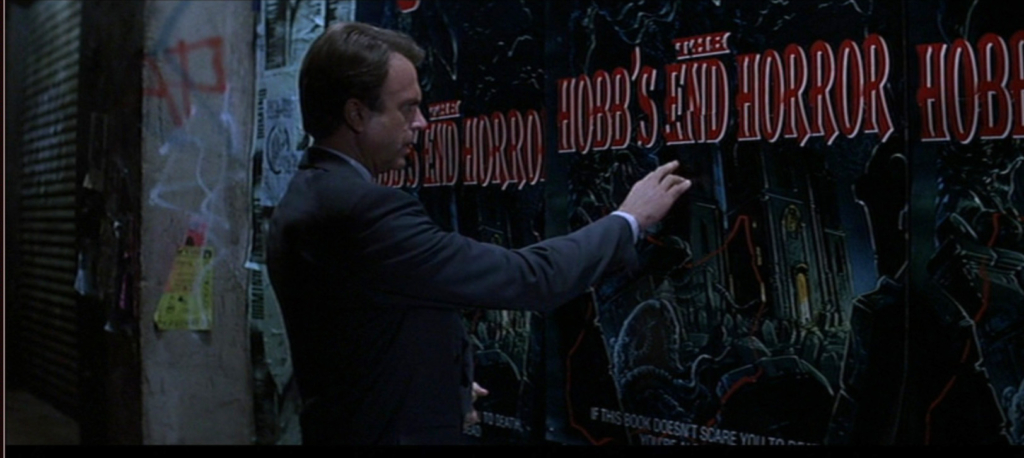

All of the fictional novels of the Stephen King-analogue Sutter Cane are familiar mutations. “The Hobb’s End Horror” is a portmanteau of the aforementioned “Dunwich” and a location from the work of writer Nigel Kneale, whose most famous character Carpenter had already borrowed as a penname for Prince of Darkness. There are tentacles and teeth and terror beyond imagination, sure.

But what In The Mouth Of Madness conjures best is the Lovecraftian sense of reality in quiet decay.

When we finally flash back to a non-institutionalized John Trent, he’s sharp, sly, and snappily dressed. He’s the perfect Lovecraftian protagonist — the best insurance investigator in the business, tasked with determining exactly what is and is not real. His philosophy is practical to the point of apocalypse, coolly punctuated with the bounce of a cigarette on his lip: “Anybody’s capable of anything…the sooner we’re off this planet, the better.”

Not far from Carpenter’s own no-nonsense, no-nothing sensibilities.

Soon as he’s tasked with tracking down the hottest horror author on the planet and the manuscript to his latest thermonuclear hit, Trent smells fraud. It’s a game, must be. Find him, “Win a Sutter Cane lunchbox.”

Trent assumes everybody’s a fraud one way or another. Styles, the editor sent to keep an eye on him. Harglow, the desperate publisher. Even the locals of Hobb’s End, like the kindly B&B owner Mrs. Pickman. Even when it all starts tilting off any natural axis, he writes it off as special effects for an exceptionally dedicated publicity stunt. As Trent scoffs at another layer of reality peeling back like a harshly turned page, Cane stops the investigator in his tracks: “Even now you’re trying to rationalize.”

In The Mouth Of Madness is weirder by volume than Prince of Darkness.

Moments of abrupt horror, be they fleeting or cyclical, pile up pretty quick. A few scrape at the edges of an $8 million budget; somebody crab-walking with an upside down head is unsettling until they crab-walk into the light. They bothered me on first watch, kitchen-sink creepiness with only a decent batting average. The jumps did me better then.

Now the jumps aren’t so bad. It’s the weird things that get me. Trent watches his framework of reality fall apart, one jigsaw piece at a time. What makes The Thing as satisfying as it is, at least in part, is how no line, no shot, no design choice is wasted. It all adds up in the end. That’s what squishy-brained film students should be studying.

But you can’t add-up Lovecraft. His monsters are written as unimaginable hulks from a vast, violent Somewhere Else. The sum is insanity. Each oddity is another notch closer to a complete dissolution of reality. Ignore at your own peril, as I once did.

Cane’s books are starting to have an effect on people.

Before Trent even takes the case, an ax-wielding madman tries to carve him up in broad daylight. An ax-wielding madman, it turns out, was Cane’s agent until very recently. Despite providing the framework — a psychiatrist played by the great John Glover mentions, “Things must be getting pretty bad out there,” on the way to Trent’s cell — the violent spell of Cane’s writing on the larger world is left in the background to provide terrible scale.

There are riots on TV when bookstores can’t keep his latest best-seller in stock. We hear passages from Cane’s work, which Trent decries to the bitter end: “God’s not supposed to be a hack horror writer.”

That’s the line that made me squirm, the same way I do when I mistake my coat on a chair for a diminutive home invader.

How many times have you seen this time, this month, this very day compared to The Stand? How many high school classmates interrupted their pyramid schemes to mention how much it all feels like a zombie movie? Now how often have you heard a coworker assess the situation as “overblown” just because they’ve never seen something like this before? How many times have you seen serious, steadfast news stories shared on Facebook just to smear the entire media as somehow dishonest in their ever-maddening dash to keep us informed?

In The Mouth Of Madness doesn’t place any blame on hack horror writers or airplane-fodder fiction.

Even Trent comes around to their dubious charms. But as soon as somebody forgets that it’s make-believe, that’s when we slip another inch toward the end. Fans rioting out of voracious entitlement. Bloody axes inspired by the latest paperbacks. Intelligent folks choosing fictional panic over studied precaution. The complete collapse of any and all logic.

What eats at the reasonable soul of John Trent is the dawning possibility that he’s only ever been a character on a page, created by a careless god to face an annihilation guaranteed long before his smoking addiction was worked in on the second draft. Is it too late? Was it ever early enough?

It almost makes you want to buy the fictional panic. There’s a poisonous comfort in knowing there’s nothing left to do but wait. In believing it.

As Cane lays plain, “When people begin to lose the ability to know the difference between fantasy and reality, the old ones can begin their journey back.”

If they’re already on the way, I hope they took the scenic route.

Follow Us!