“King Cohen” explores the enduring legacy of renegade filmmaker and relentless rule breaker Larry Cohen — part madman, part genius, wholly authentic.

A few weeks ago, I filmed in a public park without a permit, and I’ve never felt more alive. Granted, it was just a page of dialogue on a secluded trail in the middle of a weekday with two actors unarmed and unbloodied. But there’s still a school-skipping electricity to it. Or at least that faint tingle when you wandered out of study hall and hid behind the vending machines until a teacher passed by and told you to stop doing that.

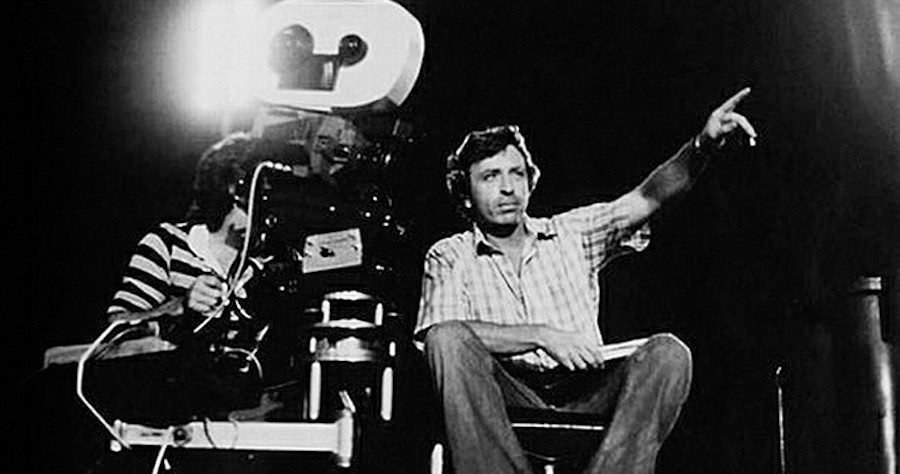

It may not earn the same adrenaline as improvising a fist-fight on an active baggage claim carousel, inciting a riot in the middle of a police parade, or driving a cab down an unsuspecting New York City sidewalk. But it all belongs to the same rebellious, inventive, and frequently illegal magic of independent filmmaking.

The only difference is that Larry Cohen’s brand of magic is now easily confused with acts of domestic terrorism.

Just about every documentary about films and filmmakers nudges the viewer in the ribs and reminds in its own way that They Just Don’t Make ‘Em Like They Used To.

Right now on Shudder, you can watch a charmingly exhaustive account of the making of Fright Night that’s almost forty-five minutes longer than Fright Night itself.

King Cohen nudges with the best of them.

You can’t talk about a filmmaker famous for improvising a fist-fight on an active baggage claim carousel, inciting a riot in the middle of a police parade, or driving a cab down an unsuspecting New York City sidewalk without acknowledging that they not only Don’t Make Them Like They Used To And You Would Rot In Jail If You Made Them Like That Today.

But then it kindly retracts its elbow and wonders, with a star-studded line-up equally wistful and worried, if anyone but Larry Cohen ever made them like that at all. If anyone remembers Larry Cohen in the first place.

Thankfully and tragically, that’s been debunked by the outpouring of appreciation surrounding his death earlier this year.

King Cohen, released only eight months earlier, isn’t so sure.

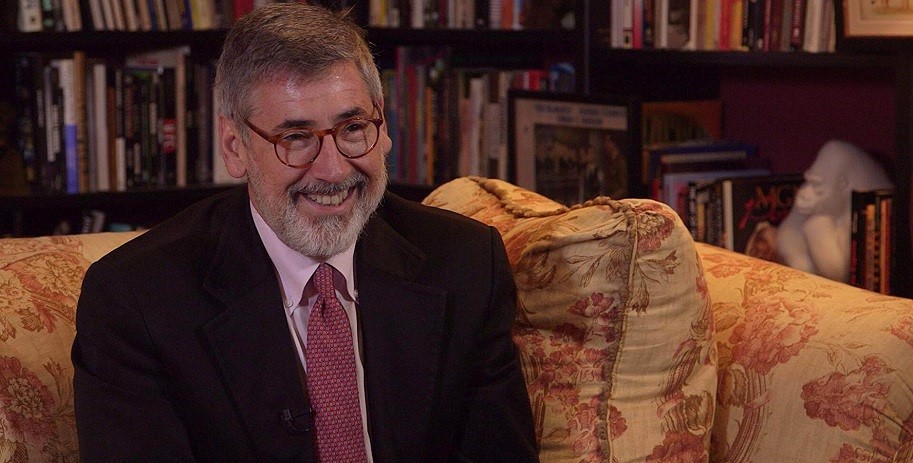

He wrote, produced, and directed genre gold with mutant babies and killer yogurt for chump change, but never had the schlock-showman immortality of Roger Corman. His anti-authoritarian streak dripped off every frame of his filmography. But he didn’t quite get the shit-kicking street cred of John Carpenter. Writer and filmmaker F.X. Feeney says it best:

“Larry Cohen is so much the invisible man…it’s entirely possible to have seen a lot of his work without knowing you’ve seen his work.”

Of course, a feature-length documentary dedicated to that work gives Cohen welcome shape, with a beginning, a middle, and what we now know as the end. He broke into the monochrome coal mines of live network TV at age 17 (that’s 1-7), cranked out scripts for every procedural your grandfather loved, and then invented several more. Remember the guy in the iron-everything from The Big Lebowski who created the TV Western Branded and wrote the “bulk of the series”? Well Larry Cohen created the real Branded, but he didn’t stick around to write almost any of the series.

Cohen was the pre-eminent Idea Man and couldn’t justify wasting years of his life on one show when he had another dozen simmering daily.

But Larry Cohen The Writer was running out of patience for bad-faith creatives and plain-bad filmmakers ruining his work.

So he became Larry Cohen The Director and eventually Larry Cohen The Producer to defend himself.

This was his Golden Age, from the early ‘70s to the early ‘90s, that defined the deceptive B-plus genius of the Larry Cohen Picture to unwary drive-in audiences everywhere. But directing takes a toll. One of his last turns behind the camera was on 1996’s Original Gangstas in the gang capital of the United States during a triple-digit heatwave.

So Cohen returned to his legal pad in the early aughts and hashed out the kind of maddeningly simple thrillers you’d swear you’ve thought of before, but only because he thought of them first like Phone Booth and Cellular.

It’s hard to pull off a two-act career making movies, let alone three, especially for someone with a vocal distaste for coloring inside anyone else’s lines.

He cringes at the term “Blaxploitation” because from his row of the grindhouse all movies are exploitation. It’s a criticism, but not a condemnation; just more switchblade honesty from one-time Borscht Belt wannabe who knows when to stick, move, and let the legend lie.

Talking about his first big hit, 1973’s Black Caesar, Cohen recounts diving out of a moving cab to convince Fred Williamson that it was a piece of cake. His story is cut short when Fred Williamson, now 80 but not aging so much as inching toward the Platonic ideal of Fred Williamson, interrupts to set the record straight: “That’s a Larry myth.”

Larry sells it with self-deprecation — after the alleged dive, he convinced his star it was painless before finding a quiet place to bruise — and the effect is the same no matter who you believe:

Somehow, Larry Cohen pulled it off.

Even for a documentary with King in the title, not much time is spent in myth-making. The opening anecdote from J.J. Abrams is no more fantastical than Cohen remembering a teenager giving him directions twenty-odd years ago. John Landis, Hollywoodland’s mythmaker-in-chief, remembers production halting on Trading Places because a maniac was rattling off machine gun fire from the top of the Chrysler Building down the street.

It certainly sounds like a legend, but it’s not. Larry Cohen hired a bunch of licensed window washers to hang off their buckets and shoot blanks at an imaginary Claymation dragon for Q: The Winged Serpent. There’s little fiction stranger than truth when it comes to Cohen, and that irresistible guerilla lunacy is as much a smokescreen as his shrug at exploitation.

Stealing footage from public places will always be a staple of independent film, but it’s not what made Larry Cohen Larry Cohen.

Joe Dante credits his “raw, visceral, realistic style.” Landis, his “attack.” Plenty of praise is reserved for the method to his madness.

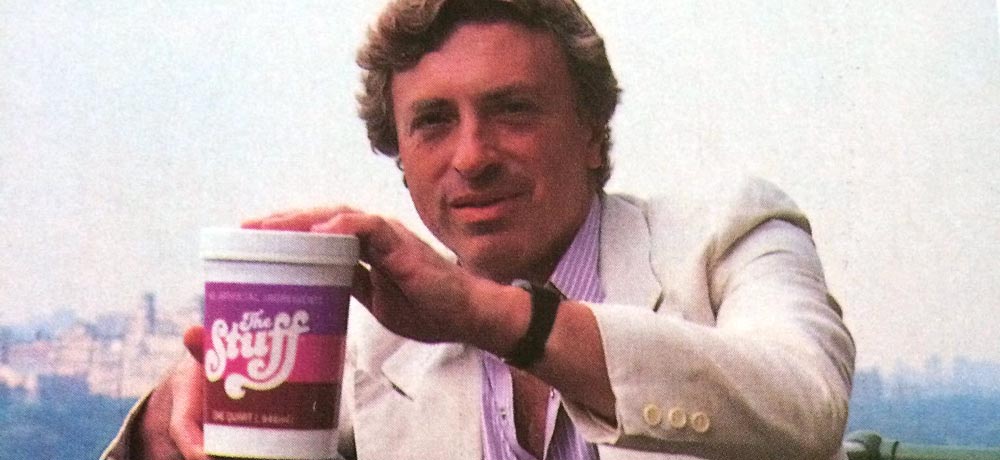

In The Stuff, he cloaked a searing takedown of consumerism in a creamy special effects splatter fest. In It’s Alive, he indicted what we now know as Big Pharma with a mutant killer baby. In God Told Me To, he explored Judeo-Christian faith by way of a police procedural that ultimately wonders if we’re all the spawn of a hermaphroditic alien lifeform. All personal, pointed subtext hiding behind a poster that’d catch eyes in every local video store.

He made movies his own, but he also made them with people movies had left behind.

For his offbeat directorial debut, Bone, he knew he needed a good cameraman and he knew he couldn’t afford one. Until he had the idea to hire the literal old guard, crew members north of sixty that grew up with the industry and aged out of it. They still wanted to work. Cohen gave it to them.

Yaphet Kotto may be overselling it by calling him, “the white Martin Luther King for movies,” but Cohen did make movies like Black Caesar and Hell Up In Harlem because it was important to him that “a few black actors got a job for a change.” When the legendary composer Bernard Herrmann died mid-collaboration, Cohen organized and paid for his funeral, a gesture that still visibly touches Martin Scorsese.

The word “maverick” is tossed around more than enough.

Cohen certainly broke the rules and improvised his own. But what makes him one-of-a-kind is how completely he defined the independent spirit and still does today. He took eye-rolling concepts, played them straight, and managed to say something between the gunfire and goop. He kept an eye on inclusion and the actors not getting nearly as much work as they should. He made movies that never would’ve survived the studio system.

Larry Cohen made movies that no one else could, on the budget of a gas station Take-A-Penny dish, and that’s what independent filmmaking is all about.

Several of the talking heads echo the same summary: “There’s really nobody like him.” They may be right. But for every independent filmmaker stealing scenes at the secluded end of the nearest public park, it’s never too late to learn from the King.

Follow Us!