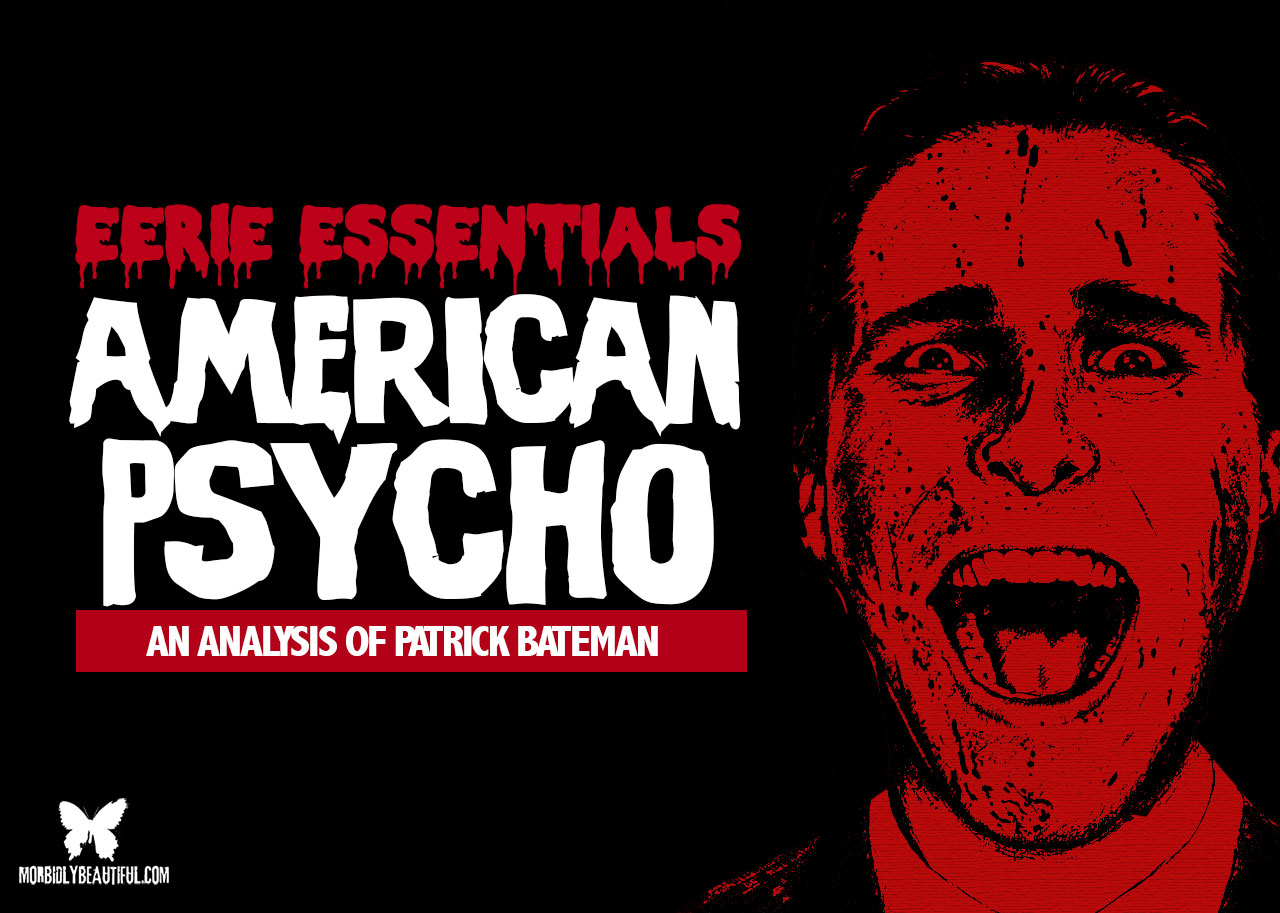

We celebrate 20 years of Mary Harron’s film adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel “American Psycho” and dissect the character of Patrick Bateman.

On today’s episode of the Patty Winters Show, American Psycho (2000) celebrates two decades of delightful decadence. So, put off returning those overdue videotapes, scooping up Broadway tickets for Les Misérables and making reservations at Crayons — you know Dorsia won’t seat you — and celebrate the 20th anniversary of American Psycho as Morbidly Beautiful deconstructs a cinematic sociopath: Patrick Bateman.

My Name Is Patrick Bateman

There are gods and there are kings — and Patrick Bateman is pretty sure he is both. Serial killers, sociopaths and psychopaths in modern horror films are often prosaic and relatively interchangeable with every other mindless killing machine (as can be seen with popular movie monsters like Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees and Leatherface).

However, Patrick Bateman is not a common man, or a common monster. Bateman is sui generis (in a class by himself); a complex creature housing juxtaposed social and serial killer personas.

“When Bateman kills, it is not with the zeal of a villain from a slasher movie,” the late film critic Roger Ebert says. “It is with the thoroughness of a hobbyist.”

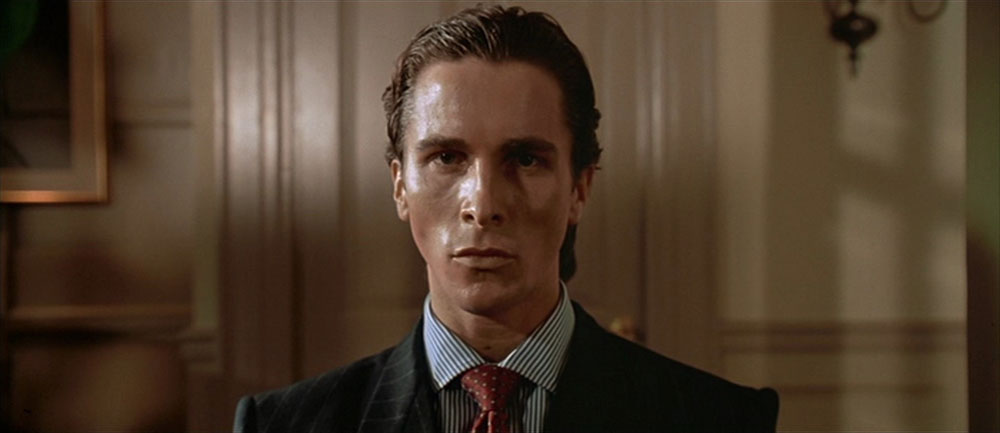

In 2000, filmmaker Mary Harron and screenwriter Guinevere Turner adapted Ellis’ novel American Psycho (1991) for the Silver Screen. Harron and Turner’s Bateman (Christian Bale) is, on one hand, alluring. He is a shrewd businessman — a yuppie by all accounts — who is a product of the caste system.

Patrick commands a six-figure income, dresses in the finest tailor-made clothing, and basks in a lifestyle desirable to many. But on the other side of the cliché coin, Bateman is deplorable. His erratic behavior swings like a pendulum from sadomasochistic sex with prostitutes to butchering work colleagues. Further, Bateman torments homeless people and total strangers unfortunate enough to cross paths with him.

Bateman’s two personas are often indistinguishable from the outside looking in, and they come and go depending on the circumstances of his day-to-day activities. It is utterly fascinating how his combination of nihilism, materialism, apathy and insecurity culminate into one of modern cinema’s most gregarious outsiders.

I Guess I’m A Pretty Sick Guy

Patrick Bateman’s unquenchable thirst for blood swells to homicidal heights thanks to his nihilistic outlook on life. A clear sociopath, he understands the difference between right and wrong, but he lacks a moral code that keeps him from indulging in his murderous impulses. Of course, that assumes Bateman is actually the serial killer he appears to be. Harron cleverly crafts the film in such a way that the validity of Bateman’s reality is purposely equivocal.

“All I wanted was it [film] to be ambiguous in the way that the book was,” Harron explains in an interview with Charlie Rose.

If Bateman is truly the monster he appears to — brutally killing a homeless bum, model, and Paul Allen (Jared Leto) — there’s no question regarding his lack of morality. But what if Bateman’s transgressive acts of murder are simply all in his head, without any presence in the real world?

Regardless, nihilism still fuels this would-be serial killer’s identity. His pervasive fantasies of slaying both strangers and those who stand in his way are heinous at best. And even if Bateman is simply hallucinating or desiring slaughter, he is still entrenched in morally objectionable activities — most notably, his proclivity for prostitutes.

In the infamous sequence where Bateman picks up Christie (Cara Seymour), and solicits an escort named Sabrina (Krista Sutton) like he was simply ordering Chinese food, Patrick instructs his two dates around in a most unsavory fashion. “Christie, get down on your knees so Sabrina can see your asshole,” Bateman commands. “Sabrina don’t just stare at it, eat it!”

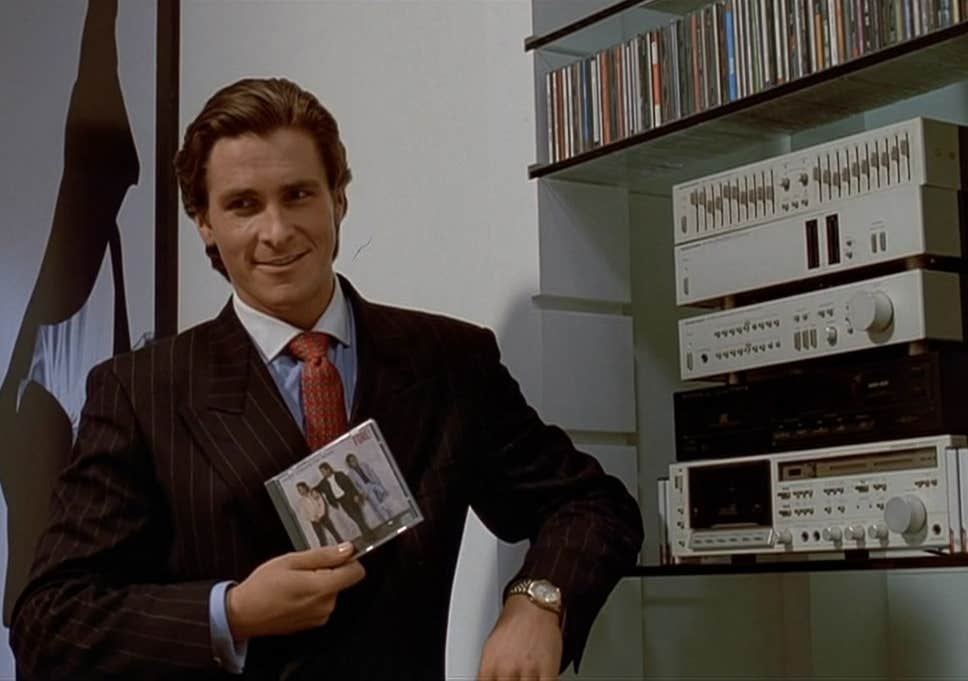

The scene is an appalling and disturbing segment, which begins with Pat critiquing the merits of Phil Collins’ music, continues with the threesome, and ends when he seriously injures both women off screen.

Patrick also has a severe detachment from reality, which further supports his nihilistic viewpoint. During an early scene, in which audiences are invited into Bateman’s apartment, Pat goes through his ritualistic morning routine. During the sequence, he explains in no uncertain terms the inner workings of his mind.

“There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me — only an entity, something illusory,” Bateman says. “And though I can hold my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours, and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable, I simply am not there.”

Patrick may indeed be a killer. But unlike other cinematic baddies, there is another side to the film’s unorthodox protagonist/antagonist.

The Mud Soup and Charcoal Arugula Are Outrageous

Bateman goes out of his way to have the very best in life, so he can be accepted by his wealthy friends and peers. During a limo ride with his girlfriend Evelyn, she questions why he doesn’t quit his job. He responds, “Because I want to fit in.” It’s jarring to witness both the serial killer and the social butterfly Bateman vacillates between. It’s equally perplexing to discover Patrick, despite his homicidal tendencies, wants to be an active and accepted member of society.

Only the best will do for Patrick when it comes to the material things in life. His apartment is in the heart of Harron’s New York City. He resides at the illustrious American Gardens Building on West 81st Street, which is a pristine example of luxury living in Manhattan. A Toshiba 30-inch television, which is state-of-the-art technology for the late 1980s, serves as a centerpiece for his home. The David Onica artwork adorning his white walls and the Valentino Couture suits, Oliver Peoples glasses and Armani ties residing in his closets all speak to the young yuppie’s material obsessions.

During an interview recorded for the DVD commentary, writer and critic Nathan Lee discusses the attraction of Patrick Bateman, despite him being a serial killer.

“Patrick Bateman is a very specific person… he’s also a kind of everyman,” Lee explains. “And although we don’t all certainly live in the lifestyle he does, what he represents and what he is living in, is really kind of a common cultural aspiration – to have that kind of money, to live that sort of glamourous life.”

So, despite Bateman being a butcher, he is also surprisingly a cool guy possessing vast riches and status. It is this side of Pat that many fans gravitate toward and ultimately aspire to be like.

I Have To Return Some Videotapes

While Pat relishes fitting in, he has a hard time caring about anything or anyone. This stark juxtaposition is difficult to fathom, but exists in the complex character narrating American Psycho. Near the film’s conclusion, Patrick decides to break up with his supposed fiancé Evelyn as she continues pushing the issue of marriage. By the end of their quarrel, Evelyn labels Bateman inhuman.

“No, I’m in touch with humanity,” Patrick retorts. “Evelyn, I’m sorry…you’re not terribly important to me.”

Earlier in the movie, as Bateman torments a homeless man named Al (Reg E. Cathey), Pat’s indifference to the destitute rises to the surface. He initially tries to counsel the bum, who lives in a desolate alley, but quickly loses interest in helping the man.

“You’ve got a negative attitude, that’s what’s stopping you. You’ve got to get your act together. I’ll help you,” Bateman says before suddenly shifting gears. “Al, I’m sorry. It’s just that I don’t have anything in common with you.”

Bateman then proceeds to tell Al what a loser he is before stabbing him to death. And then, in the most distasteful of displays, Patrick stomps Al’s little dog — the animal’s bones crush and crunch under the monster’s heels like fragile peanut shells.

In a less lethal example of apathetic behavior, Patrick is having an affair with Evelyn’s best friend Courtney Rawlinson (Samantha Mathis). Courtney is married to Luis Carruthers (Matt Ross), but Bateman doesn’t care in the least. He’s also completely indifferent to the fact he believes his best friend Timothy Bryce (Justin Theroux) is having an affair with Evelyn. It is this sort of sordid behavior which makes Patrick so unlikeable, but so utterly intriguing.

Actor Christian Bale, who gives a virtuoso performance in the movie, discusses Bateman.

“I like nothing about him,” Bale says. “He’s certainly somebody that I wouldn’t want to be at a table with, and eating, but I’d certainly want to eavesdrop on his conversation.”

We Should Have Gone To Dorsia

Peer pressure is yet another contributing constituent to Patrick Bateman’s riveting identity. Along with his desire to fit in with others, Bateman often allows his friends to dictate his social behavior. In fact, it can also be argued peer pressure helps to quell Pat’s basest cravings. During one of the film’s earliest scenes, Bateman joins Evelyn, Bryce, Courtney, Luis, Vanden (Catherine Black) and Stash (Park Bench) for dinner at a fancy restaurant. Patrick is uncomfortable beforehand as he reveals in the film’s narration.

“I’m on the verge of tears by the time we arrive at espace, since I’m positive we won’t have a decent table,” Bateman worries. “But we do. The relief washes over me in an awesome wave.”

The evening passes, as the friends enjoy their time together. But immediately after, Patrick looks to satisfy his inner serial killer. Bateman comes across an attractive, nameless woman after visiting an ATM. He flirts with her, and she seems agog, as the pair walks away together. The next morning finds Pat arguing with a laundry attendant over bleaching some blood-stained evidence: Cerruti bedsheets he and the nameless woman shared the night before.

And later, after a seemingly friendly exchange with his work colleagues over new business cards, Bateman takes to the streets of New York in search of more blood. No longer under the influence of his so-called friends, he murders the aforementioned homeless bum and offs the man’s beloved dog.

The most glaring evidence of the influence of peer pressure on Bateman comes at Evelyn’s Christmas party. Patrick socializes with those in attendance, and even good-naturedly sports a pair of reindeer antlers on his head, courtesy of his girlfriend. But following the festivities, Bateman finally makes his move on rival co-worker Paul Allen. Pat invites his workmate to his apartment and bludgeons Allen to death with an axe.

This Confession Has Meant Nothing

Patrick’s peculiar combination of attributes results in one of the cinema’s most compelling and unpredictable sociopaths of all time. Just don’t call him a psychopath.

According to Dr. Kelly McAleer (Psy.D): “Compared to the psychopath, the sociopath will not be able to move through society committing callous crimes as easily, as they can form attachments and often have ‘normal temperaments.’”

And in a study for Psychology Today, Dr. Seth Meyers (Psy.D) asks:

“Are sociopaths bad people? It’s easy to utter a full-throated ‘Yes!’ for so many reasons, but the reality is that sociopaths don’t necessarily have malicious feelings toward others. The problem is that they have very little true feeling at all for others, which allows them to treat others as objects.”

As this analysis of Patrick Bateman’s complicated and compelling character ends, remember the words of author Bret Easton Ellis:

“This is not an exit.”

…

Follow Us!