Bob Clark’s “Black Christmas” is a rightfully beloved and thought provoking piece of horror cinema that is still extremely relevant to the women of today.

It’s always easy to write off horror movies as solely for entertainment fun. There are certainly ones that are simply there for the sake of entertainment, but to reduce them all to just that would be a disservice to the genre as a whole. Horror movies have often echoed the issues of the times that they were made. Looking back, some of horror’s greats have created films that speak to the social and political climates of era in which they were created. The creators’ anxieties, fears, hopes, and observations are thus embedded into the film.

Romero gave us Night of the Living Dead, Craven gave us The People Under the Stairs, Hooper gave us The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and so on and so forth.

Some horror films are subtle in their messages and themes, while others are overt in what they’re trying to say. One could sit and list many horror classics that are beloved and respected that have deep meanings that deserve to be uncovered and analyzed. In fact, the subtext and analysis of these films makes them all the more dear to the viewers. These films can give comfort in times of great strife and upset — bringing about catharsis, and making the viewer feel spiritually cleansed and at ease.

In 1974, Bob Clark gave us a little film about a group of sorority sisters being terrorized by an unknown assailant during the Christmas season.

Black Christmas is a creepy and sly look at the terror involved in being a young woman, and it still rings true today for many, many viewers.

The film mainly follows heroine Jessica “Jess” Bradford, played expertly by Olivia Hussey, a woman that is ahead of her time. Even in today’s society, she would still be considered radical for her thoughts, actions, and attitudes toward traditional gender roles that are unfairly imposed on women. In addition to Jess, the piece is peopled with more vibrant characters who refuse to stick to the stereotypes of the time. This includes Margot Kidder’s brash and foul-mouthed Barb, who refuses to be the acceptable demure and simpering portrait of a socially acceptable woman.

The framework of Black Christmas is based on society’s grave oversights when it comes to the safety and well-being of women.

Even though Black Christmas was made in the 70’s, the issues that the film presents still persist.

The young women in the film continually alert the police that there is something dangerously wrong going on. Clare goes missing, and little is done in respect to her disappearance. In the midst of Clare’s mysterious absence, another girl who was walking home from school disappears as well. The sorority sisters receive continuous vulgar and threatening phone calls that are constantly disregarded and brushed off.

It’s nothing new for the police to shrug off the concerns of women only for there to be deadly results. Most of the film features Jess’s fraught pleading with the police to be taken seriously. She is aware that there is something desperately wrong, and so are her sorority sisters and those associated with them. But there is very little outside help to be found for the young women. John Saxon’s Lieutenant Fuller is the only person on the police force who takes the girls’ plight seriously. But alas, one believing party can only do so much when irrevocable damage has already been done.

There have been numerous times that women will notify police in the hours, days, weeks, and even months before they are brutally murdered by a man — whether that man be a boyfriend, an ex, an old friend or acquaintance, or stalker.

The way the police are dismissive of the sorority girls parallels an extremely real problem that is still an issue in this present day.

For example, in October of 2018, Melvin Rowland murdered Lauren McCluskey. McCluskey was a 21 year old student at the University of Utah. Rowland, 37, was McCluskey’s ex and a convicted sex offender who had done time in jail. Earlier in the month, McCluskey had broken up with Rowland after learning that he was lying about his age as well as his past as a convicted sex offender. McCluskey called police six times in the ten days before her murder. Rowland was seen stalking around the university campus, hoping to catch McCluskey and confront her. Rowland went on to fatally shoot McCluskey in the head in a campus dorm while she was with friends.

Lauren McCluskey is not the only woman that has suffered a similar fate.

33 year old Laura Stuart warned police about her ex 18 times leading up to her brutal murder. Three days before Stuart was murdered, she informed police that her ex was threatening to “finish her.” Stuart’s ex, Jason Cooper, stabbed and kicked Stuart after attacking her on the street. Stuart succumbed to her injuries in the hospital two days after her run in with Cooper.

Shana Grice, 19, filed a report against her ex for physically assaulting her, only to have her report dismissed after she had failed to disclose she had been in a relationship with the man who had assaulted her. The police fined her for her “false report.” Months later, the ex, Michael Lane, had stolen a key and broken into Grice’s apartment. The police responded by simply ordering that Lane stay away from Grice. One short month later, Grice was found with her throat slit and her assailant had attempted to burn her body. Unsurprisingly, Lane quickly became the police’s chief suspect.

Banaz Mahmod, a 20 year old woman, went to the police on five different occasions before her father and uncle orchestrated her rape and murder. Mahmod’s family had forced her to marry an older abusive man when she was only 10 years old. The family was aware of her treatment and did nothing to stop it. Years later, Mahmod left her husband and fell in love with another man. Mahmod’s father and uncle felt that her actions had dishonored the family, and she soon learned about their machinations, prompting her to go to the police. Mahmod was dismissed every time she sought the police’s help. Her murder was typified as an honor killing.

McCluskey, Stuart, Grice, and Mahmod are just a few notable examples of how police have failed women in real life situations that mimic the elements found in Black Christmas.

Cursory Google searches can find more women who have suffered fates that are similar. Dismissing the concerns of women often leads to dead women. It’s a simple mistake that is made time and time again, yet there seems to be no action to combat this. How many more lives have to be lost due to police negligence for law enforcement and the public in general to notice?

Black Christmas is discussing this issue and has been facilitating discussion surrounding it since 1974. Viewers who claim that Black Christmas doesn’t facilitate such necessary discussion are being purposefully obtuse for the sake of derision.

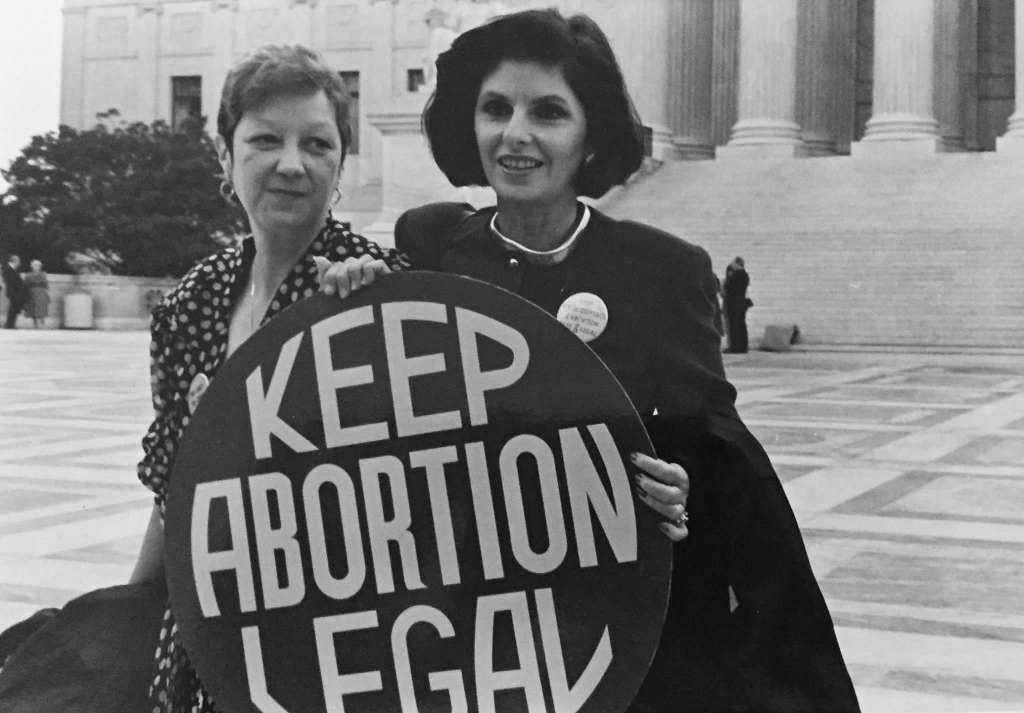

Jessica spends much of the movie in terror, worried for the well-being of her sorority sisters despite having her own personal problems to deal with. Early on in the story, we learn that Jess is pregnant and plans to get an abortion.

The film came out only a year after the historic case of Roe v. Wade took place in the United States.

Jess tells her boyfriend Peter, a pianist, that she plans to end her pregnancy. It is made clear that this is an issue that Jess has deliberated with gravity, and her mind is made up. Instead of supporting Jess and empathizing with her situation and point of view, Peter becomes verbally abusive toward her. He insinuates that Jess is selfish and that he should have a say in her termination of the pregnancy. He tells her that she will change her mind and that they will be married.

Peter doesn’t offer marriage as a solution, he demands it. He attempts to change Jess’s mind multiple times, each time becoming more forceful with her. He intends to bully Jess into motherhood and marriage, something that she isn’t ready for. In the face of Peter’s petulant rage Jess is a stalwart beacon of calm reasoning. She doesn’t give into his browbeating. She doesn’t give into his own selfishness that he fails to see. The language he uses when talking to Jess about the situation reveal that Peter is a controlling person at heart and seeks to make Jessica submissive to him and his desires.

As the film goes, on viewers begin to realize that this might have less to do with the idea of Jessica aborting his baby and more about his desires to control her. He doesn’t take her point of view into consideration, even though she willingly tells him how she feels about her pregnancy and her reasoning. Peter is belligerent and filled with rage because Jess refuses to bend to his will. At one point he throws a tantrum and wrecks a baby grand piano in the process, all stemming from his own anger at Jess and how she will not obey his whims.

Jess’s quiet firmness and rationality provides an interesting and powerful foil to Peter’s rash and domineering character. Jess seeks to untether herself from him and his expectations of her, and it drives him mad. For a character that has the accusation of selfishness hurled at her, Jess is quite selfless.

Some of Black Christmas’s most tender and altruistic moments are those between Jess and her sorority sisters as they struggle to find a solution to the chaos surrounding them.

She readily provides her friends with comfort and puts her own issues on the metaphorical backburner. Clark refuses to paint Jess in a negative light just because she is exercising her right to choose to end her pregnancy. Jess’s bonds with Barb and Phyl are beautifully delineated, though she is portrayed very differently from them. The sisters have diverse and vibrant personalities. And while they all differ, they are bound by their deep love and respect for one another.

Sisterhood isn’t presented in a facile way in Black Christmas. It is deep and it is abiding. The girls care for and truly look out for one another.

Connections between women are on full display and depicted as being beneficial and essential. In the face of devastating circumstances, these connections are the strongest presented.

When Jess is informed that the calls they have been receiving are coming from inside of the house and for her to vacate the premises immediately, she refuses to leave. She instead arms herself, prepared to fight for her sisters. At the time she is unaware that Barb and Phyl have already met bitter fates, but they are her main priority in the moment. Jess is willing to throw herself into danger, against an unknown assailant. It’s a heroic act from a woman who has been denigrated as selfish for much of the film.

While Jess provides a foil to Peter, it can be said that Peter himself parallels Billy, the mysterious killer.

Both are motivated by pure toxicity that is directed toward women.

Thus, the film sets up Peter as a red herring of sorts. The audience is already quite sure that Peter is not the killer at hand because it would be far too obvious. But due to Peter’s intense anger, Lieutenant Fuller suspects he may be the culprit they are looking for. They serve as a meditation on toxic masculinity and men whose rage is primarily centered on women. Both operate on a sense of male entitlement to the women around them.

Peter feels like he is entitled to Jessica and to make her decisions for her. Billy feels entitled to take the lives of young women that he comes across. Women are merely disposable or something to possess in their worlds. Neither afford women any ounce of autonomy or dignity with their actions. Even in one of Billy’s vile phone calls that Jess answers, he echoes Peter’s sentiments involving Jess and her choice to end her pregnancy — further proving that the two are mirrors of one another and connected in an analytical sense.

Billy is the main villain at hand, but that doesn’t make Peter any less of a villain in his own right due to his abusive actions toward Jess.

Clark’s decision to keep Billy’s identity in the film shrouded in mystery lends to the idea that he could be any man who kills women just because he can, just because he has the power and enjoys doing so.

Clark had a backstory mapped out for Billy, but the deliberate exclusion of it in the film speaks volumes. It doesn’t matter what Billy’s past was like. What matters is that he is now senselessly killing women and that he is a monster for doing it. His monstrous acts are the focus, not his past. The exclusion of Billy’s backstory also allows Clark to keep the focus on the sorority sisters and tell their stories as opposed to dwelling on the killer.

Billy might be the killer, but this is not Billy’s film. This film belongs to Jess, Barb, Phyl, and the other sisters. It allows Clark the time to build upon their characters and give them the rich texture that they deserve instead of building up the killer and making the victims paper thin caricatures. The viewers care about these young ladies, and that makes their peril all the more chilling to watch.

Clark carefully endears us to Jess and lets us become involved in her struggle. We fall in love with Barb and her unapologetically brash nature. We come to adore quiet and steadfast Phyl. We wish that we had a mentor in our lives like the lovably audacious Mrs. Mac. We want Clare’s death to come to light and justice to be served. Clark refuses to give Billy the narrative and instead gives it to the women. For the 98 minute runtime, these girls become our friends and our sisters, and that makes the film so much more affecting.

Black Christmas has always been a film criticizing inaction and toxicity.

It’s impossible to ignore how unsubtle this film is in its beliefs, and it’s wholly disingenuous to willfully pretend that the messages the movie has simply do not exist. It’s outright ignorant to claim that there aren’t blatantly feminist undertones in this woefully underseen and misaligned horror flick.

Black Christmas has never simply been a film made to just solely entertain. It’s always been a loudly radical film. You just might not have been paying attention.

3 Comments

3 Records