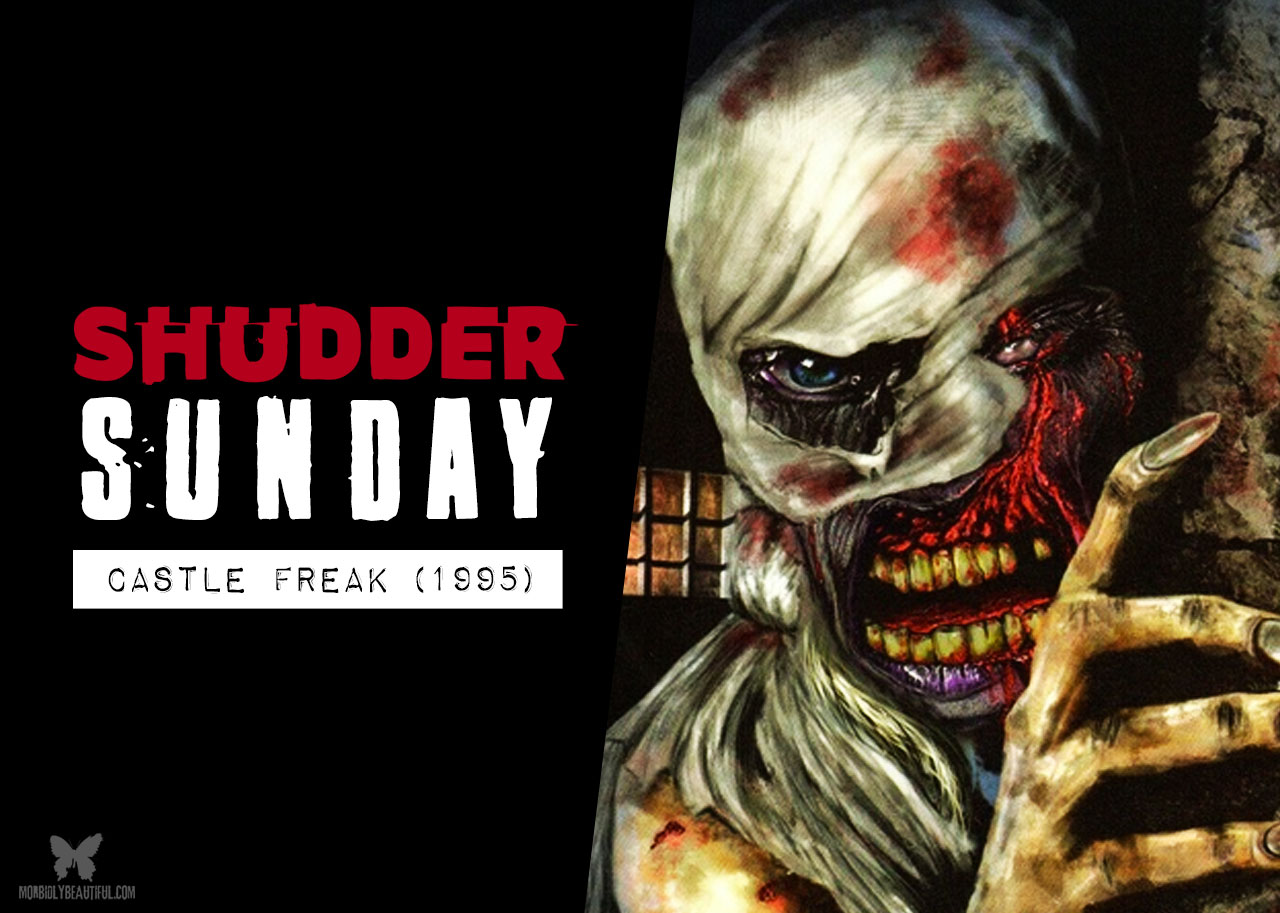

The loosest of Stuart Gordon’s Lovecraft adaptations is also the hardest to watch, as much for the nasty things in the basement as the nasty things in us.

Like most masters of horror, Stuart Gordon was one of the last suspects you’d pick out of a lineup. He looked and sounded like a high school art teacher just happy to be there. Considering all the younger filmmakers now sharing stories of Gordon’s encouragement, he acted like one, too.

By his own admission, the first movie that scared him was Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. “I had nightmares for about three years after I saw that movie,” he chuckled in an interview with Fangoria.

Re-Animator, his now-legendary entré to the genre, was borne out of as much practicality as passion. Once some of his Organic Theater company bailed for Hollywood, he decided to make a movie showing off the actors who stuck around, and horror was the easiest sell.

His sudden absence is all the stranger on the eve of a Lovecraft renaissance.

Richard Stanley is planning a trilogy of his works off the indie momentum of Color Out of Space. Jordan Peele is executive producing a TV adaptation of “Lovecraft Country,” Matt Ruff’s novel that transplants the author’s unknowable monsters and latent racism to the American south. One theatrical release this year was retroactively turned into a Lovecraft movie through the magic of post-production.

Without Stuart Gordon’s five trips to that dark well where things slither and swallow minds whole, how would we remember H.P. Lovecraft today?

This Shudder Sunday is now the second in a row about his work, the last about John Carpenter’s most honest homage. So it’s not like the father of cosmic horror was hurting for fans.

Gordon, though, celebrated him by doing the unthinkable: making his anti-humanism achingly human.

To say Castle Freak is based on Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” is like saying Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Psycho are accounts of the same true story. It’s true in most courts, but an oversimplification that does a disservice to all the text involved.

It’s just as accurate, if not more so, to claim Castle Freak is based on a poster that was hanging in the office of Full Moon founder Charles Band when Stuart Gordon was developing Space Truckers. The art showed a chained-up creature halfway between man and monster getting whipped in a dungeon. Band famously answered: “Well, that’s a castle and there’s a freak.”

If Gordon could make a feature-length film including those key ingredients for under $500,000, Band didn’t care what he did with it. So with complete control of the project, Gordon enlisted his Re-Animator and From Beyond cowriter Dennis Paoli and found the closest Lovecraftian source material.

“The Outsider” is about a lonely soul trapped in a castle that’s never known natural light.

They one day decide to escape, climbing the stairs in the tallest tower until they crumble and scaling the rest of the way. Once free in what seems to be another world, they seek out the nearest sign of life and find a grand party in a far less cruel castle. As soon as they arrive, something horrifying sends the assembly screaming for the doors.

Then they see it: “a compound of all that is unclean, uncanny, unwelcome, abnormal, and detestable.” Lovecraft goes on, but you get the point. The abomination that scared everyone away is hideous beyond human comprehension, and the lonely soul is looking in a mirror.

It’s a knife-twist of an ending, turning “The Outsider” into the rare Lovecraft story told from the perspective of the Horrible Other.

Castle Freak takes the mirror and the monster’s reflection and hides them in a broken home drama.

Jeffrey Combs and Barbara Crampton return from Re-Animator and From Beyond to close out their Gordon-Lovecraft trilogy with the quietest, cruelest roles of the bunch.

John Reilly is an on-the-wagon alcoholic who crashed his car while driving drunk, killing his five-year-old son and blinding his older daughter, Rebecca. Susan Reilly can barely stand to carry her husband’s last name, let alone sleep next to him.

Castle Freak finds them forced to play nice in front of Rebecca after John unexpectedly inherits a castle in Italy from a somehow-related Duchess.

The titular freak chained up in the basement eventually complicates things, but the marital rift is what gives the movie its pulse.

On Mick Garris’s Post Mortem podcast, Combs lamented that Re-Animator scored him few job offers that weren’t just Herbert West knock-offs. By 1995, Crampton was more known for her soap opera work than the goopier stuff.

Against all odds, the movie that started as a two-word concept on the producer’s wall is their finest hour.

Neither part is as flashy as their flip-flopped roles of Mad-Doctor and Doomed-Subject in Re-Animator and From Beyond, but they’re immediately, painfully human. There’s a flashback to the fateful accident that broke the Reilly family, but if you happened to miss it while making popcorn, you’d still feel everything you need to feel.

Castle Freak has a reputation. It’s not an easy watch.

That’s usually attributed to the late-game brutality, like when the freak bites off a woman’s nipple, among other parts of her anatomy. No question, that’s tough to sit through. But what sets this movie apart from the rest of its unofficial trilogy, and most cult classics in general, is the deafening lack of a punchline.

The monster is a monster. You can’t cheer at the violence and you certainly can’t laugh at it either. Nobody cracks wise. Most argue, saying only the kind of things that can’t be unsaid, let alone forgotten.

“So what’s left? You just punishing me?”

“Yes, because God didn’t. He just let you walk away without a scratch.”

It’s not the kind of dialogue you see on t-shirts at conventions, but the bruise is souvenir enough.

But what of the titular freak?

He does have a name, but giving too much away about him would rob the movie of some mystique. All we need to know, to truly understand him, is provided before the opening credits.

He lives in a windowless cell, chained to a wall. He eats only scraps of bread and sausage left almost out of reach by an elderly caretaker who whips him before each meal. The only sound he makes is one of the most unnerving in horror cinema, the agonizing wail of child through the tortured vocal cords of a man. That last part may be subjective, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

To his credit, Jonathon Fuller didn’t need any more noises to make the freak a living, breathing soul.

In no time at all, the latex scar-tissue of John Vulich fits Fuller like a second skin. There’s no seam between prosthetic and performance, even in Gordon’s cruelest close-ups. His missing-cheek grin inspired many a rental when Castle Freak went direct-to-video, but his laundry list of deformities are never leered at. He may be the monster lurking around in the dark, but Stuart Gordon didn’t direct a sideshow.

Instead, the freak is an uncomfortable reflection.

He does see himself in a mirror, like in the source material, but that happens early and he’s too primal to expound on the psychological fallout of such a revelation. Understandably, he breaks the mirror and runs away. It’s not his own reflection that gives him such profound menace, but John’s.

The first night in his mysteriously inherited castle, John tries to charm his estranged wife into bed by calling her Sleeping Beauty. As soon as she rejects his advances, he reminds her how long he’s been sober, like she might offer intimate pity.

To him, the trip is a fairy tale reconciliation. The more he realizes he inherited a very different kind of castle, the more he loses control. The more he loses control, the closer the freak gets to his family. John hangs around a little too long in the wine cellar. The freak sneaks into Rebecca’s room and gets close enough that she knows someone’s there, even if she can’t see them.

It all builds to Castle Freak’s most notorious scene, when the freak mauls a prostitute.

I can’t argue it’s not viscerally grotesque. But I can say, in context, it’s bone-deep disturbing.

John finally loses his grip and goes out for a drink. He’s once again the careless id that irrevocably fractured his family. A prostitute takes a shine to him and he invites her back to his wine cellar. There, John puts on the moves. Sloppily and, in the end, embarrassingly. The freak watches him and, after John goes to bed, chains the prostitute in his cell.

Everything he does is a gory, misunderstood pantomime of what John did earlier. He doesn’t know why he’s doing it. She’s clearly in pain. But he doesn’t stop.

In a way that Gordon’s other Lovecraft works aren’t, Castle Freak is a character study.

The Reilly family is stuck in a fairy tale castle on a hill with the monster that ruined their lives. When a newly sober John is arrested for the prostitute’s murder, Susan and Rebecca are left to fend for themselves against the writhing naked shape in the dark. When the freak runs into the hallway behind them, for a moment it looks like some earlier evolution of man.

To the Reillys and the little hairs on the back of our neck, it is.

Stuart Gordon never took horror for granted, even in a movie based on two words and a poster. It’s a powerful testament to his filmography and his spirit that everybody involved turned in some of the best work of their careers, even in a movie about a castle and a freak called Castle Freak.

Follow Us!