This month, we all celebrate the wonderful moms in our life. So our writers thought it was a great time to explore themes of motherhood in horror.

Each month, our staff picks a cinematic theme and recommends our favorite horror films related to that theme. Last month, we celebrated the season of change by bringing you our 13 favorite transformative horror films. This month, we continue celebrating the undeniable impact and influence of the moms in our life — and the joys and challenges of being a mom — by exploring the complex themes of motherhood in some of our favorite horror films.

Important Note: We dive deep to explore the rich and multi-layered themes of our favorite genre films. As a result, spoilers abound. Please proceed with caution. We suggest watching each of these films, if you haven’t already, before diving into these reviews, unless you are unbothered by potential plot spoilers.

1. GOODNIGHT MOMMY (2014)

Recommended by Megan Hopkin

It wouldn’t be fair to delve into a list discussing the morbid world of motherhood without mentioning a jewel in the crown of 2014 international horror releases; Goodnight Mommy. Heralding from Austria, directed lovingly by Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala, the deceptively titled Goodnight Mommy steers far from being a tender celebration of motherhood. In fact, the metaphorical veering from the street of Benign Mother Loving would be so great, that you launch directly off the cliff of Moderate Momma Liking – into the sea of Fuck You Mom. In case my metaphorical mother geography is too difficult to follow – Goodnight Mommy does not end with a relaxing bubble bath for Mommy painstakingly drawn by her children (sorry for the spoiler).

To summarize: a pair of twins, Elias and Lukas, becomes increasingly suspicious of their mother following her return from cosmetic surgery. Heavily bandaged, her face is completely obscured, which sparks initial discomfort for the children – yet the real worries derive from the mother’s treatment of Elias. Refusing to interact with Lukas at all, she focuses her attention entirely upon Elias – oftentimes lashing out at him for his behavior.

Alongside this, Mommy’s apparent aversion to sunlight within the home and her insistence on the boys staying within the house to play despite the warm weather inspire Elias and Lukas to question their mother’s identity. Has she been replaced with an imposter? Or is it much more sinister than that?

The film ripples with paranoia, with every shot of ‘Mommy’ painfully laden with a sinister sense of otherness. Oh, and on the note of pain – this film’s use of practical effects offers up several teeth-gritting scenes which look excruciating. Not to ruin anything, but I now involuntarily wince at the super glue tube at the bottom of the messy drawer.

Where Goodnight Mommy thrives is through cinematography. Each scene is painstakingly shot in a way that captures youthful joy and excitement, as well as childhood fear.

The palpable sense of fear deriving from questioning just what lays beneath Mommy’s bandages encourages the viewer’s mind to contort frightening images as it might have in their youth.

Although the aforementioned practical effects utilized within this flick are done well and offer up scares in themselves, the true root of the uncomfortable viewing in Goodnight Mommy comes from Elias and Lukas. The boys’ inability to fully communicate their grievances to their mother, and thereby relying on their wondering imaginations for answers, infect the viewer alike. Mommy is transformed into a monster through fancy alone.

Indeed, the gap between parent and child is heightened through an inability to actively communicate difficult emotions. Using a small set to stage the events of the film, relying heavily upon the grounds of the house and the inside of the family house itself, the concept of emotional distance can be more effectively explored. Despite the characters being boxed in together, the emotional disconnect between mother and child is made all the more palpable.

Goodnight Mommy sparks an interesting debate as to what makes ‘Mommy’, mommy. The young boys’ suspicions surrounding their mother’s authenticity are sparked largely through her surgical bandages – the result of cosmetic surgery. This is highly symbolic, as the physical change in Mommy links to the emotional change in her. I also suggest that there is significance in the surgery being cosmetic – this was a surgery that was not ‘necessary’. Instead, it is an act of individuality that grants the mother pleasure that extends outside of those given from family life.

This act of individuality ultimately changes her in the eyes of her sons, who only see her as ‘Mommy’. The onslaught of tension that occurs between the sons and Mommy may be symbolic of the tumultuous inner struggle of mothers, struggling to meld their new maternal identity with their original, independent identity.

The film also offers an insight into the self-destructive role that grief may play within motherhood. Mothers are often seen as the head of the household, offering emotional stability for the rest of the familial unit. The emotional sacrifice that comes with this is rarely seen. Yet is viscerally explored within this film, as sorrow is thoroughly weaponized by the climax of the flick. Grief becomes the basis of which motherhood is irreversibly tainted.

In conclusion, Goodnight Mommy ponders what makes a mother in a way that is gritty, painful, and unsettling in equal measures. One has no choice but to ponder as the credits sluggishly roll – was Mommy really the true antagonist of the movie? Or was it the boys, with their conceptions of motherhood, who were the wrongdoers all along?

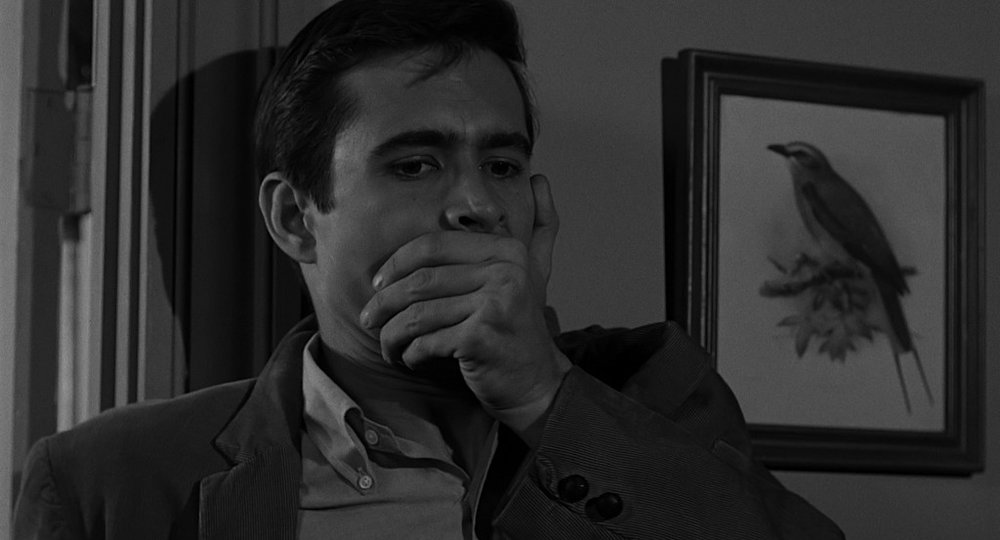

2. PSYCHO (1960)

Recommended by Todd Reed

Domineering mothers in movies is a classic trope. Over the years and across genres, we’ve seen it over and over again. But it has probably never been done quite as well as Alfred Hitchcock did it in the 1960 classic Psycho.

For the sake of this article, I’m only going to focus on the original. Norman Bates’ relationship with his mother has been thoroughly examined in both the series Bates Motel and also in the made-for-TV movie Psycho IV: The Beginning. It would be easy to fall down that rabbit hole and to also include Vera Miles’ domineering mother, Lila Crane, intent on revenge in Psycho II. But that may be an article for another day.

In Psycho, Hitchcock doesn’t show us the mother and son relationship. Instead, he shows us the horrible aftermath of Norman’s relationship with his mother. Initially, the viewer is led to believe that Norman lives in the house above the hotel with his mother. She is controlling, critical, and castrates any attempt Norman makes to seek a normal relationship. Norman capitulates to all of this, and after the death of Marion Crane, we start to believe that he is covering for his mother.

When it is finally revealed that Norman‘s mother has long been dead and it is Norman himself bringing his mother to life, we realize the depth of the damage that she had inflicted upon him.

Despite the horrible things Norman does in the movie, in the end, we realize that it is not Norman who is the monster (he wouldn’t harm a fly), but it was his mother whose behavior shattered a young boy’s psyche and turned him into someone completely broken. Hitchcock paints a horrifying picture of just how devastating the mother-child relationship can be when the mother is intent on raising her child to be dependent on her.

3. MAMA (2013)

Recommended by Jamie Lynn Alvey

Andy Muschietti is now widely known for bringing Stephen King’s horror epic It to the big screen. But years before that, he burst onto the scene in 2013 with a humble ghost story called Mama. Mama is a full-length adaptation of Muschietti’s chilling short by the same name. Narratively, Mama harkens back to an earlier era in cinematic horror and owes a great deal to the sweeping tradition of gothic horror. Muschietti doles out chills as well as truly touching moments in the equal and effective measure in his debut film.

Mama can be called a film about two mother figures. The central plot follows Annabel and her partner Lucas after Lucas’s nieces are found after years of living in the woods. Many years prior to the plot, Lucas’s twin brother killed his wife. He planned on killing their daughters, Victoria and Lilly, and himself in the woods before the ghost Mama intervened and saved the girls. The whole time the girls were cared for by Mama.

Annabel and Lucas eventually take guardianship of Victoria and Lilly after a minor custody battle with the girls’ maternal great aunt. They have an agreement with Dr. Dreyfuss, a psychologist who is studying the sisters, to move into a home provided by the institution he works at so he can continue his studies. Not long after the move, Lucas is injured by Mama and falls into a coma, leaving Annabel to care for Victoria and Lilly.

When the audience first meets Annabel, she is taking a pregnancy test. She sees that the result is negative and rejoices. Together Lucas and Annabel live a bohemian lifestyle, her being a bassist and him being an artist. They’re the last couple you could picture caring for children. After Victoria and Lilly are rescued, she finds herself to be extremely conflicted about having what can be considered a ready-made family.

A friend of Annabel’s urges her to leave Lucas. But like life, love is complicated. Annabel’s not the sort to leave him holding the bag. After Lucas’s accident, she’s left alone with the girls and her life becomes even more chaotic. You have a pair of kids who long for Mama, the only mother they’ve really known, and a woman who never asked to be thrust into a motherly role.

A jealous ghost doesn’t necessarily need to be in the equation to complicate matters; Victoria, Lilly, and Annabel experience growing pains and difficulties before coming together as a cohesive and loving unit. All the while, Annabel remains firm in her identity. Her edges aren’t sanded down just because she’s bonded with her pseudo nieces. Amid the supernatural disturbances and the trials that come with caring for children with past trauma comes genuine sweetness. Annabel grows into a mother figure in her own right and on her own terms. This may not be the ideal situation for her, but she is taking initiative and finding what works for her in it.

Mama, our most overt maternal force in the film, is the ghost of a former mental health facility patient named Edith Brennan. Mama has her own tragic backstory that involves having her child taken from her in the asylum, eventually resulting in her killing a nun and escaping with the child. When cornered, Mama jumps off a cliff with the baby and kills them both. Ever since Mama has wandered the woods searching for her lost child.

Victoria and Lilly have filled the void caused by the loss of her child. And when her mothering role is encroached upon by Annabel, she feels threatened and becomes more desperate to get the girls back.

There is an interesting dynamic created by juxtaposing an overprotective ghost mother with a resistant punk rocker who is slowly making a found family with her partner’s nieces. The film stresses an important factor in being a mother or a guardian: one does not need to be related to the children in question to love them and care for them.

Undoubtedly, Jessica Chastain shines as Annabel. The film marks her first foray into the horror genre, though as we know now it would not be her last. Chastain brings a richness to Annabel that makes her a character easy to identify with. After all, are we all not trying to deal with the various curve balls life throws at us?

Javier Botet brings real heart and horror to the role of Mama. It would be a crime not to mention how well he embodies the misshapen and twisted pain of the character in his performance. Botet has become a staple in modern horror and deservedly so, breathing life into the ghosts of Crimson Peak and Eddie’s leper in It: Chapter One.

Game of Thrones fans will surely recognize Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as Lucas and his twin brother Jeffery. And while he does play a significant part in the film, his character and performance take a respectful backseat to the sheer forces of Chastain’s Annabel and Botet’s Mama.

For a first film, Mama is a beautifully delineated effort that manages to stick with the viewer in many bittersweet ways.

4. INSIDE (2007)

Recommended by Jamie Marino

Not until recently have I questioned Inside. I’ve never stopped loving it. But I got to thinking about the different kinds of “motherhood” Inside addresses.

There are two movies that can still cause me to have anxiety attacks: Martyrs and Inside. At first glance, Inside is a deceptively simple movie. Sarah (played by Alysson Paradis), a young wife and expectant mother, is widowed by a tragic car accident. Although she chooses to carry the baby to full term, all life has clearly been drained from her heart. She goes through the empty motions of the ultrasound alone, stuck in a seemingly forever-grey world, and her expressions are a complete holocaust of mourning and sadness.

Her closest friends and family attempt to take both physical and emotional care of her as best they could, but she is not interested in life of any kind, including the baby she is soon going to give birth to. And so we arrive at our first thought-provoking examination of an aspect of motherhood: a possible talking point about whether or not it is “right” and “moral” to have a child not only out of wedlock but without a father.

It is a unique and incendiary question to ask since the film makes no effort to intentionally lead the viewer in any particular direction. The startling part is the fact that after losing her husband, she loses interest in her baby as well. I tried to empathize, but I stumbled all over my thoughts. I think if it were me, I would be thankful that I (and the baby) remained unharmed. I would love and appreciate life even more. In my opinion, it takes neither a village nor two parents to raise a wonderful child.

Then the Big Bad (Béatrice Dalle) enters the picture, throws you on a rollercoaster without safety bars, and shreds your seatbelt.

On Christmas Eve, Sarah is spending the night in solitude. Her apartment is flooded with hazy, warm, and cozy homespun colors which somehow make the extreme violence to come even more distressing. A strange woman in black knocks on Sarah’s door and asks to use the phone. The woman has made no effort at all to resemble a comforting and friendly presence, so Sarah immediately denies her access. The woman then indicates that she knows a lot about Sarah, including the car accident and her indifference towards the child growing inside her. The woman in black thinks she deserves the child more and plans on collecting. Then the rollercoaster drops vertically at an unbelievable speed.

The woman gains access inside Sarah’s home, and for the next ninety-odd minutes the two women tear each other to pieces in a cat – and – mouse explosion of stabbed faces, flare gun mutilations, brain impalements, multiple crotch impalements, throat impalements, squishy bellybutton stabbing, and a gorgeous and very realistic aerosol spray burning. At one point in the movie, while traumatically injured, a victim screams for her mommy. This scene made me feel very uneasy, watching someone in so much pain instinctually resort to the very basic primeval need for mommy.

Questions flow into my mind when the movie ends. Was Sarah defending herself, her baby, or both? When she was fiercely fighting for her life, was she concerned for her child too? Or did she finally develop a mothering instinct and loving heart? Did the woman in black have a more righteous and authentic love for the child? We can really go “out there” and ask if the woman in black did indeed deserve the baby more. You’ll enjoy chewing on those questions after the twist. Yes (sigh) there’s a twist. But it has a purpose beyond simply showing off narrative cleverness.

Once Inside gets going, it never lets up. The film’s championship high school track team pace and unpredictability make it an exceptionally suspenseful and exciting experience. I felt a pinching vulnerability in my lungs while watching it. I was at the mercy of the filmmakers and had no idea where the blood was going to come from next.

WARNING: I have been told that this movie can dramatically upset pregnant women.

5. HEREDITARY (2018)

Recommended by Vicki Woods

In a perfect world, mothers are supposed to love, nurture and protect us. In maternal horror films, the mother in question fails to protect their children. Hereditary hits all the levels of motherhood gone wrong. From the very beginning, you can feel the awkwardness in the Graham household. The feeling of heavy, dark, and angry energy follows every character. It’s like their lifeforce is slowly bleeding out of their bodies. This is a grim and troubled family.

The film begins with a funeral for Ellen, Annie Graham’s (Toni Collette) mother. Annie gives the most depressing eulogy for her late mother that I’ve ever heard. There is no love lost there and the audience begins to wonder, “why”? The story unfolds slowly and carefully; the “why” when revealed, is horrific.

In Hereditary, motherhood and grief are the primary themes of the film, all the way to the incredibly creepy and disturbing finale.

Annie is lost. She obviously had a horrible childhood and through her art of tiny dioramas, we learn how her mind has come to be in a morbid place.

Annie experienced deep loss early on, with the suicide of her mentally ill brother and a father who starved himself to death; leaving her alone with a mother who has an agenda of her own. We don’t know the details of that agenda until further into the movie.

But as the audience figures it out, we realize everything bad that happens was orchestrated by Annie’s dead mother. The patriarchal mother, the one they are supposed to trust, literally eradicates their chance to be happy. Annie never learned how to be a loving mother; she never had that with her own and has no one to turn to for help.

Annie’s damaged childhood, and evil influences, leave her withdrawn and prone to sleepwalking. Unbeknownst to her, Grandmother Ellen had placed a demonic spirit named Paimon into her granddaughter Charlie (Milly Shapiro) and now needs to move it permanently into grandson Peter’s (Alex Wolff) body. In one of her sleepwalking episodes, Annie wakes to find she has covered her children in paint thinner and has a lit match in her hand.

Oddly enough, this was probably the most loving thing could have done for her children, as she would have protected them from the demon that her mother set free. Subconsciously she must have known that her primary role in life was to give birth to a boy that will eventually host the demon.

The horrible chain of events started years ago by Grandma, including the brutal death of daughter Charlie, leaves the family grief-stricken and beyond help. Having a strong positive maternal bond in the family could have helped them all. But from there, it spirals downhill, deeply out of control.

The first time I saw the film at The Overlook Film Festival, writer/director Ari Aster shared that “The film’s primary aim is to upset audiences at a very deep level.” That it does.

6. XX (2017)

Recommended by Tavera del Toro

XX looks at a female perspective from the lens of family, motherhood, and the supernatural. The film is not a perfect movie, but there are places that touched home and leave behind a great-lasting fear in your mind.

The film XX is significant because it focuses on the horror viewpoint of women (XX, the sex chromosomes of a female).

It features four stories directed by women, with the subjects varying from the supernatural to the darkly comedic. But three of the stories center on moms and the apprehension they endure.

The first segment, The Box, directed by Jovanka Vuckovic, is the eeriest of the anthology. It’s truly frightening, as it includes an underlining subtext of the mother not being the classic mom. She is the breadwinner, and her husband is the homemaker. Because of this, she feels excluded. She feels guilty when a nameless horror befalls her family. And it will torment her eternally, even though she was at no fault.

The Birthday Party, directed by Annie Clark, is the least serious of the narratives. But even that story illustrates how others struggle to cope and shelter their offspring from the grim realities of life. It revolves around the frantic mother, who runs through hoops for a birthday party for her daughter. And it finishes with a sinister laugh.

Don’t Fall, by Roxanne Benjamin, was the aberration of the stories. It felt out of place with the others, because it lacked the motherhood connection. Brisk and to the point, it felt a bit like an incomplete story.

My prime choice is the finale, Her Only Living Son, directed by Karyn Kusama. This is a tribute to a specific iconic horror film (I won’t divulge the name). The short introduces us to a mother troubled by her sole child’s behavior. He is in high school, and she becomes even further confused when others in their lives overlook or aid him in his evil activities. The segment concludes with a quick and bloody end — and a suggestion on what happened to the original film’s characters. The unfortunate ending brings to rest one of horror’s enduring mysteries (the original film’s sequel, notwithstanding).

Although the anthology leaves you seeking more, I fell in love with the segment fillers/shorts produced by Sofia Carrillo. They are creepy yet majestic and leave the viewer haunted. With a Victorian gothic flair and unnerving quality, you can’t help but feel enchanted by them.

But I highly recommend you watch the film for yourself and experience the world through a mother’s eyes.

7. SILENT HILL (2006)

Recommended by Richard Tanner

I’m going to get a little deep with you guys… I’m a mama’s boy. Sadly, I also had to deal with the death of my mother at an early age. So, please forgive me if I get a little too biased here.

I’ve always been partial to women leads in horror movies. But I always thought it was because they were vulnerable — until I saw Silent Hill. That movie took the ideals of feminism and shattered them. No longer was it about competing with men. Instead, it was like, “How did men ever believe they were on the same level?”

Silent Hill came out in 2006 as an adaptation of the popular video game… I might add, the scariest video game I had ever played. The story followed a woman, Radha Mitchell, searching for her daughter in a foggy hellscape that I still see in my dreams. Despite the fact that I was screaming in the theaters at the slightest twitch of a creature, here was this woman diving headfirst into all that I feared… for love.

It wasn’t stupidity or bad writing. This was the strongest character I had ever seen written. She broke the rules of horror films and was still a hero.

Every character in this film was a strong mother-like character. From the cop, Laurie Holden, who wanted to protect the innocents at any cost (even burning for that belief), to a cult leader who ruled her congregation with an iron fist.

Hell, I’d suggest that the weakest character to come out of the movie was the biggest name, Sean Bean. Bean played the dad that was always one step behind and in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I think the idea of “a mother being God in the eyes of a child” is something we can all relate to. And anything that threatens that is true fear.

We may not all have children, but we have all had a mother. And nothing can stop that.

8. DEAD ALIVE (1992)

Recommended by Alli Hartley

Amidst the sentient intestines, the monstrous babies, and the buckets of blood, it’s very easy to forget that the true evil in Dead Alive (aka Braindead) started long before the Sumatran Rat Monkey. Peter Jackson’s low-budget cult classic, known as one of the goriest movies of all time, is at its heart a struggle for a man to break free of his domineering mother.

Of course, that struggle is harder when you’re stuck inside her.

When Lionel Cosgrove (Timothy Balme) meets the beautiful and vivacious Paquita (Diana Penalver), his mother Vera (Elizabeth Moody) jealously follows the couple on their date to the local zoo. While there, Vera is bitten by an unholy abomination, the Sumatran Rat Monkey. Vera’s bite festers and her body begins to rot from the inside. Lionel struggles to keep up appearances, but Vera dies, only to come back as a zombie. She attacks the attending nurse, who becomes a zombie as well.

Lionel struggles to keep his mother sedated. But through a series of misadventures, Vera attacks and turns several others. Lionel keeps them all in his basement and cares for them as best he can. But Lionel’s greedy uncle arrives and soon finds the zombies. Mistaking them for regular corpses and mistaking Lionel for a necrophiliac, Uncle Les blackmails Lionel into handing over the house and Lionel’s inheritance. It isn’t long before Les invites all his friends over to the house to celebrate.

Will the zombies attack the partygoers? Will Lionel ever see Paquita again? And what does dear old mother think about all this?

In a movie that features a son literally cutting his way out of his mother’s stomach, you know mommy issues are rampant. Even after she’s gone, even after her ear falls off and her eyes ooze milky white, Lionel still plays the dutiful son.

For Lionel, years of manipulation and abuse have worn him to be less than a person. By the end of the film, it’s clear there’s truly nothing like a mother’s love.

9. THE OTHERS (2001)

Recommended by Josh Ludwick

My nomination for mother of the year goes to Grace Stewart. Now you must be wondering two things. First, who the hell is Grace Stewart? Secondly, why does she deserve mother of the year?

The answer to the first question is easy. Grace is the mother of Nicolas and Anne. She is also the wife of Charles. It was also the fictional name of Nicole Kidman’s character in the 2001 thriller The Others.

Her nomination for mother of the year comes from her ability to care for her children. She was willing to do this at all costs.

While waiting for her husband Charles to return from WWII, Grace and her children lived in a mansion in Jersey, France. The children were given food and plenty of books. Nicolas and Anne received their own nanny and even had someone to clean the house and keep the grounds.

Mrs. Stewart made sure the children were never exposed to light. Both Nicolas and Anne suffered from a rare condition that makes them allergic to sunlight. To avoid exposing them, she had all the windows covered with dark drapes. Grace would also prep the rooms before her children would enter to make sure no light would be there or get in.

At one point, Grace thinks someone has entered the house, so she brandishes a shotgun in an effort to protect the family. It is all in vain because she finds nothing. As the noises continue, so does the paranoia. But Grace cannot keep the children from feeling unsafe.

Of course, the title of mother of the year is bull. The reality of her parenting style was that she was the farthest thing from being a good mother. Grace never believed anything Anne had to say. As a penalty for ‘lying’, the children would be separated and forced to read scripture from the Bible.

Her paranoia made her suspicious of all that tried to help her. She refused to accept that she could have made mistakes, so she blamed everyone else for creating the noises or not locking the door.

In the end, the viewer finds out that the whole family is dead. It is revealed that Charles really died in the war. The big twist at the end is not that the family is dead, but that Grace killed her children and then took her own life.

The movie The Others became Nicole Kidman’ s projection of the life she wished she could have provided for her children. It showed how the stress of trying to protect her family actually caused Grace to go over the edge. In the end, her fears became her reality. The irony of Mrs. Stewart’s situation was that the thing that should normally be feared (ghosts) was actually the thing that could help her understand her tragic situation.

10. WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT KEVIN (2011)

Recommended by Stephanie Malone

It may not exactly be a horror film — at least not in the traditional sense of the word. You’d probably be more inclined to call it a dark drama or a psychological thriller. In spite of that fact, We Need to Talk About Kevin is one of the most disturbing and, yes, truly terrifying films I’ve ever seen. It got under my skin and burned its way into my psyche like few films have ever done.

Like Darren Aronofsky’s Mother!, another film that would have fit very comfortably on this list, We Need to Talk About Kevin is a complex and layered film addressing a multitude of important themes. But the heart of the film is the atypical bond, or lack thereof, between a troubled boy named Kevin (Ezra Miller) and his beleaguered mom Eva (Tilda Swinton).

Swinton gives a tour-de-force, career-defining performance in the film as a mother struggling to come to terms with her son and the horrors he has committed.

The story is told from Eva’s perspective, through different timelines. There’s present-day Eva, a broken shell of a woman who’s lost everything — struggling with the unbearable guilt of having failed her son as a parent…and failed society by raising a monster. We also get flashbacks of Eva’s life as a mother to a budding sociopath — from her unwanted pregnancy to her struggle to connect to a contemptuous child.

The film addresses complex questions of nature versus nature. Was Kevin born bad, or did Eva’s obvious shortcomings as a parent trip that dark switch in him? From very early on, she knows there’s something wrong with her son. But no one will listen. In the end, however, it is she who shoulders the blame for Kevin’s unspeakable actions. If there’s something wrong with Kevin, there must, in turn, be something wrong with her.

Watched in a vacuum, outside of any real world cultural and socio-political context, the film is absolutely chilling. But viewed with fresh eyes in light of the world we currently live in, it’s almost unbearably gut-wrenching and brutal.

We Need to Talk About Kevin was adapted from the 2003 novel of the same name. Its storyline was heavily inspired by the tragic events at Columbine High School in 1999, when two teens went on a shooting spree, killing 13 people and wounding more than 20 others before committing suicide. At the time, it was the worst high school shooting in U.S. history that left a nation shocked, horrified, and desperate for answers.

When a school shooting happens, we assume the child murderer had bad parents, that they failed in some unforgivable way. We need someone to blame – and that someone is, without fail, the mother. We Need to Talk About Kevin approaches this sensitive issue from a new perspective, showing us the horror from the lens of the mother the world is quick to condemn.

There are no easy answers in this film, and certainly no happy endings. It’s bleak, nihilistic, and heartbreaking. It’s also absolutely brilliant.

You don’t have to be a parent to be affected by this film on a deep emotional level. But if you are a parent, especially a mother, We Need to Talk About may just be the most frightening film you’ll ever watch.

BONUS: THE BABADOOK (2014)

Recommended by Claire Smith

Jennifer Kent’s debut film, The Babadook premiered in 2014 at the Sundance Film Festival. The story follows a single mother/widow, Amelia, as she attempts to raise her unusual son, Sam. As if life isn’t hard enough with Amelia trying to cope with the tragic death of her husband and raising a troubled boy alone, things are about to get much worse when they accidentally unleash a terrifying being named ‘The Babadook’ through a strange storybook.

Although the film may well be a metaphor for the grieving process and mental illness, it also provides a take on the difficulties of single motherhood.

Amelia receives little to no help from family or the community due to Sam’s erratic behavior. Her slow descent into madness may well be a nod to the overwhelming task of raising a child alone without support of any kind. Amelia is also plagued by her faint desire to give up on motherhood and retreat back to the past. This is reflected when the Babadook, disguised as her late husband, demands that she ‘give him the boy.’

However, the ultimate defeat of the Babadook lies within her ability to save her son and address her declining mental state. Strangely, the harrowing events of the haunting end up bringing them closer together.

In the end, she also grows to mother the Babadook, which now remains locked in the basement. We learn that the Babadook cannot be destroyed or eliminated. The only way to survive it is to face it, come to terms with it, and find a way to make peace with its presence. While clearly a metaphor for grief, it also brilliantly reflects the endless journey and battle that is motherhood.

…

Follow Us!