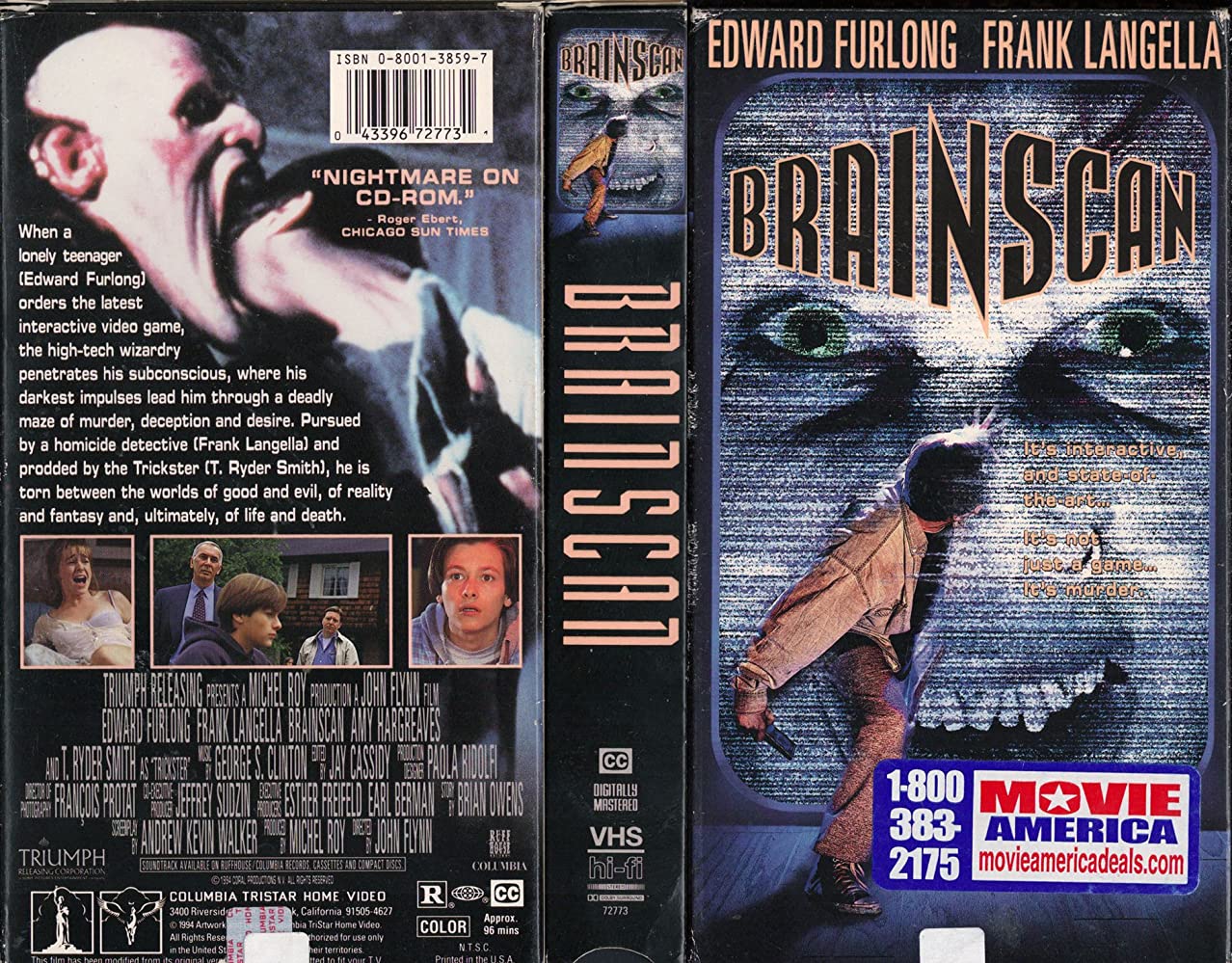

Video Rewind tells the stories behind forgotten VHS favorites from the video store era, one rental at a time! This month’s movie is 1994’s “Brainscan”.

The early 1990s saw a changing landscape in the horror genre. Freddy was dead in 1991, Jason went to hell in 1993, Chucky wouldn’t be seen again until 1998, and Michael Myers was limping toward the new millennium without much of an impact. With the slasher horror villains of the 1980s seemingly falling out of favor, there looked to be a void to fill. Could a new horror villain be established in the 1990s in the wake of Freddy, Jason, and Micheal?

Many films would try, and if they weren’t directed by Wes Craven, they would fail. One of these movies was released in 1994, merging early ’90s youth culture with a new horror villain that blended the wisecracks of Freddy Krueger with a ’90s attitude. The film was Brainscan, and the new horror villain on the block was Trickster.

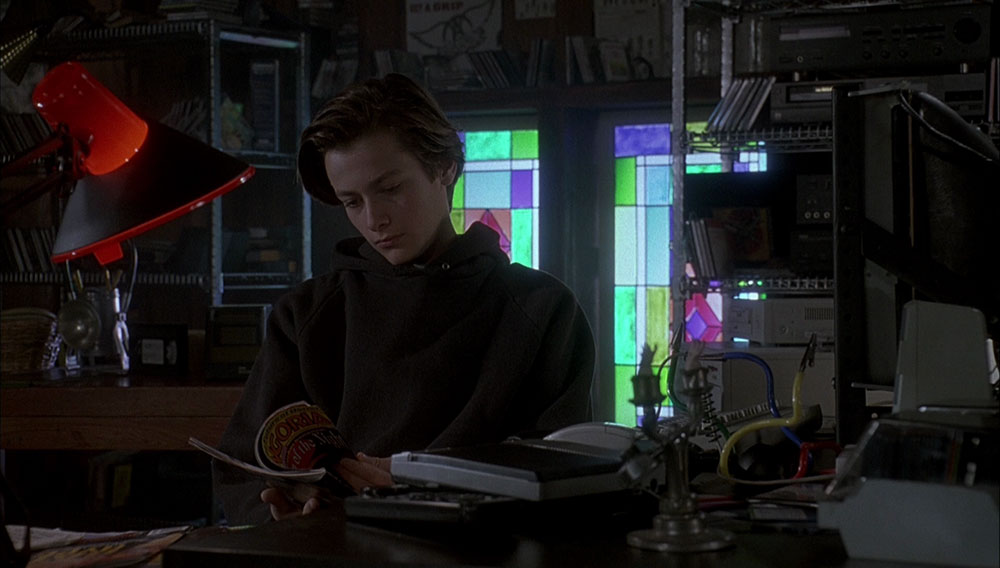

Brainscan tells the story of Michael (Edward Furlong), an isolated teenager who spends the majority of his time watching horror movies and playing video games (Furlong himself was a self proclaimed video game addict at the time). Instead of picking up the phone or knocking on her door, Michael gazes across the street through the window of his fellow teenage neighbor Kimberly (Amy Hargreaves), even recording her as she does simple things in her bedroom like comb her hair or…erm…change her clothes. Perhaps a bit creepy (or a lot), but Kimberly seems to know she’s being watched and kind of plays into Michael’s voyeurism.

He’s not a bad kid, and Kimberly knows this, but Michael sure as hell has some high social anxiety to deal with. His friend Kyle (Jamie Marsh) is just as much a misfit as Michael, albeit a more outgoing one. They’re both members of the horror club at school where they watch horror movies with a few other students.

“What was that film you were watching,” asks the principal in a low-key disgusted tone. “Death, Death, Death,” answers Michael, waiting a beat to add, “Part 2.” “Oh, Lord,” responds the principal, flabbergasted as to why someone would watch such filth. The principal goes on to ban the club, leaving Michael feeling like more of a misfit than ever.

This is when Kyle tells Michael about a new video game called Brainscan that promises a virtual, life-like experience.

Edward Furlong had no ambitions for an acting career. The young actor-to-be was approached in Pasadena, CA, near his hometown of Glendale by a casting director who was looking for a kid to star alongside Arnold Schwarzenegger in his next big budget action movie. Furlong won the part and would be playing John Connor in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, a box office juggernaut that would be the biggest movie of 1991. The film’s huge success sky-rocketed Furlong into instant teen idol status, one of Hollywood’s hottest young stars, and earned him an MTV Movie Award for Best Breakthrough Performance.

At 13 years old, Furlong lived the kind of success that few get to experience, and the young actor had the world at his fingertips.

Three years after Terminator 2, Edward Furlong was in need of a hit. Pet Sematary Two disappointed a year later, failing to reach $20 million at the box office (the first brought in $57 million in 1989), and 1993 saw Furlong star in 2 box office bombs in American Heart and A Home of Our Own, despite starring A-listers Jeff Bridges and Kathy Bates, respectively (Furlong himself earned a Film Independent Spirit Award nomination for American Heart). At just 16 years old, Furlong was in jeopardy of losing the gigantic momentum playing John Connor had provided him and his unexpected acting career.

The opportunity for a starring role seemed like the right choice for Furlong’s career.

The perfect teenage embodiment of early 1990’s grunge-rock America with his half-length hair, sleepy eyes, and soft spoken, semi-surfer sounding voice, Edward Furlong was an inspired choice to portray Michael in Brainscan.

“I saw your ad in Fango,” Michael says after dialing the 1-800 number to order the Brainscan video game. They show him looking through Fangoria magazine, barely flashing half the title on the cover. Kudos to the filmmakers for using the Fango slang and knowing the film’s true audience would get it. After all, in the pre-internet age, kids around the country probably read all about Brainscan in the beloved horror magazine. The ones that actually showed up to see it, that is.

When the game arrives, Michael eagerly begins to play. Once hooked up to the mentally invasive Brainscan experience, Michael shoots through an animated wormhole into a digital reality where he must successfully commit a murder while leaving behind no evidence to link him to the heinous act. “Do it, what are you waiting for,” prompts the Brainscan voice-over as Michael holds a knife above the sleeping victim. “Make sure he’s dead,” the voice encourages after Michael stabs the victim a few times. Michael obeys the game and continues to stab.

He jolts awake, sweating and breathing heavy. “Oh that was intense…far out,” Michael says between gasps. It’s a borderline orgasmic response to the grisly experience, one that leaves Michael feeling energized and invincible as he turns up the volume of his stereo to compete with a loud outdoor party next door. “How about that,” he yells at the party. Furlong is pretty great in this scene as a teenager feeling on top of the world, fueled by the testosterone rush of getting away with murder. Michael feels safe, justified even, to feel so elated because it’s just a game. At least he thinks it’s just a game.

Of course it’s not just a game, this is a horror movie after all!

Michael is downright horrified to learn that the “virtual” murder he committed playing the game was anything but virtual. Under some sort of hypnotic state, Michael really did brutally stab that man and kill him while playing the Brainscan game. It’s this point in the film when Trickster, the voice from the video game, exits the TV screen and physically enters into Michael’s bedroom to tell him the game isn’t over. Michael must “play” again because there was a witness to Michael’s actions, and they must be killed.

Like Freddy Krueger, Trickster manifests himself during an unconscious state. But once he’s been welcomed into this state, he begins to show up while you’re awake, making your life a living hell with seemingly no way to stop it.

Trickster looks like a coke head, glam rock, punk version of a Keith Richards doppelganger — a sadistic reject from Nightbreed‘s Midian.

“Real, unreal, what’s the difference? As long as you don’t get caught,” reasons Trickster when Michael pleads with him that he can’t kill again. Michael can watch the endlessly gory Death, Death, Death Part 2 with his horror club at school and not bat an eye, even half smiling as he watches. But when Trickster snaps back his own fingers and digs his Nosferatu fingernails into his eyes, leaving blood trails down his face, all to prove he’ll never tell what Michael did no matter what is done to him, Michael can barely stand to watch, wincing and flinching.

At this point, Michael knows the difference between real and unreal as the guilt of what he’s done weighs heavy on him.

Screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker didn’t come up with the idea of Trickster.

His original idea was to have the Trickster character as only a voice on the phone when Walker completed the third draft of the Brainscan script in January of 1989. Walker doesn’t know who did the rewrite, “maybe the director for all I know,” he says. But it’s the rewrite that came up with Trickster as an actual character that walks around on screen in human form. The idea of a physical character was a smart one, as it presented a possible franchise character in the vein of Freddy or Jason.

A franchise never did come to pass, and Brainscan vanished pretty quickly from the box office. But Walker would have two massive hits by the end of the decade with Seven (1995) and Sleepy Hollow (1999).

What’s interesting about the rewrite that added Trickster is that when actor T. Ryder Smith got the part of Trickster, he was told it was largely just an off-screen voice. Smith agreed to the voice part but got a call a few days later from the filmmakers asking if he was allergic to make-up. This suggests that the now mostly on-screen, physical form of Trickster was created after the actor who accepted the role to play him was cast.

Smith was not allergic to make-up, and the application to transform him into Trickster began at 4 in the morning and took over 4 hours to complete, with an additional 90 minutes to remove it at the end of the day. The rigorous make-up process didn’t hinder the enjoyment the theater-trained Smith got out of portraying such a theatrical character.

Having shared all of his screen time opposite the young actor, Smith said Furlong was a “prince” and a “good guy” who was going through a tough time in his life.

Behind-the-scenes footage shows the two riding around the studio lot, Smith in full Trickster make-up, riffing on each other and having a good time. It’s easy to see that Smith took a liking to Furlong, and vice-versa. Smith felt that Furlong was under immense pressure as a hot new star and trying to navigate that is difficult for any actor, especially at such a young age. Throughout the 1990s, Furlong would gain a reputation as being difficult to work with, making it safe to assume that Smith wasn’t far off with his observations that the pressure of Hollywood was getting the best of the young star.

Director John Flynn didn’t share Smith’s glowing view of Furlong while on set of Brainscan.

He did not get along with his star, and didn’t hide his feelings during one interview saying, “Eddie Furlong was a 15-year-old kid who couldn’t act. You had to slap him awake every morning. I don’t want to get into knocking people, but I was not a big Eddie Furlong fan.” Saying the actor in your movie can’t act is a pretty harsh statement. If Furlong frustrated Flynn on set, then it’s fair for the director not to recall him fondly, but Furlong gives a solid performance in Brainscan and does exactly what is needed for his character.

On the other hand, Flynn had nothing but good things to say about veteran actor Frank Langella, who played Detective Hayden, (billed as Detective, but introduces himself in the film as Lieutenant). Flynn said, “Frank Langella is a prince of a guy and a wonderful actor.” Funny that Flynn used the same word to describe Langella (prince), that Smith used to describe Furlong. Flynn continued his praise for Langella saying, “he really nailed that character. He played against the tough cop stereotype, played it very gently and softly, but there was a subtext of steel. His Detective Hayden character had a very human concern for the boy, but he was going to find the truth.”

Flynn’s take on Langella’s performance (unlike Furlong’s), is accurate.

As proven in 1979’s Dracula where he played the title character, Langella has a strong screen presence that immediately commands the viewer’s attention. This holds true in Brainscan, where his Detective Hayden genuinely cares for Michael’s well being, but will do whatever it takes to find the truth as he begins to see connections between Michael and the murders. “I heard a lot about you from your classmates,” Hayden says to Michael. “I hope good stuff,” responds Micheal with a crooked smile. “Well no, to be perfectly frank, Michael, you were described as frightening.”

With his smooth, calming, yet deeply authoritative voice, Langella indeed offers much to the role, in addition to serving as a grounding presence to the far out story of the film.

As Michael grows more nervous about being sent to jail for murder, Trickster continues to pester him to kill one more time, another witness that must be taken care of. It was the idea of Trickster that really attracted Flynn to the script in the first place, further evidence that Flynn may have been responsible for creating the human form of the character in possible rewrites. While Flynn found Smith’s performance of Trickster to be “extraordinary,” he may have gone a little too far trying to push Trickster as a possible character to build a franchise around.

At times scary, at times downright goofy, sometimes appearing as a villain to Michael, other times his friend, it’s hard to pin down exactly what the character of Trickster is supposed to be. Is he a ruthless villain pushing Michael to murder for his own enjoyment? Or is he more of a punk rock uncle figure, helping Michael find out who he really is? At once Brainscan plays like Freddy Krueger in A Nightmare on Elm Street and like the teenage version of 1989’s Little Monsters.

This broad, please-everyone approach is more confusing than satisfying, and is the film’s biggest hindrance.

Released in theaters April 22, 1994, Brainscan was not well received.

Gene Siskel, of Siskel & Ebert fame, said he thought the film wouldn’t be successful and that Trickster is an annoying character in the vein of Drop Dead Fred (1991), and referred to the character as a “low rent Beetlejuice.” Audiences weren’t enticed by Trickster, and Furlong had another box office disappointment on his resume as Brainscan opened with a paltry $1.7 million in over 1,200 theaters. The film barely cracked the top 10 of the box office at #10, narrowly beating out Schindler’s List in its 19th week of release.

Any hopes of a Trickster franchise were dashed.

Brainscan is a slick looking film. The picture is crisp and the colors are vibrant, a presentation choice that aligns with the cutting edge technology featured in its story. While the story certainly has a gritty edge to it, the need for a roughed up image isn’t necessary and is wisely avoided because it’s the allure of the new Brainscan video game technology, (the shiny new toy, so to speak), that serves as the catalyst for the grisly events of the film.

And if the character’s place in the story is hard to pin down, Trickster being both shiny, glam rock and dirty, punk rock at the same time compliments the story lines nicely. The music from George S. Clinton does the same, blending modern guitar and electric keyboard with old school, orchestral horror arrangements.

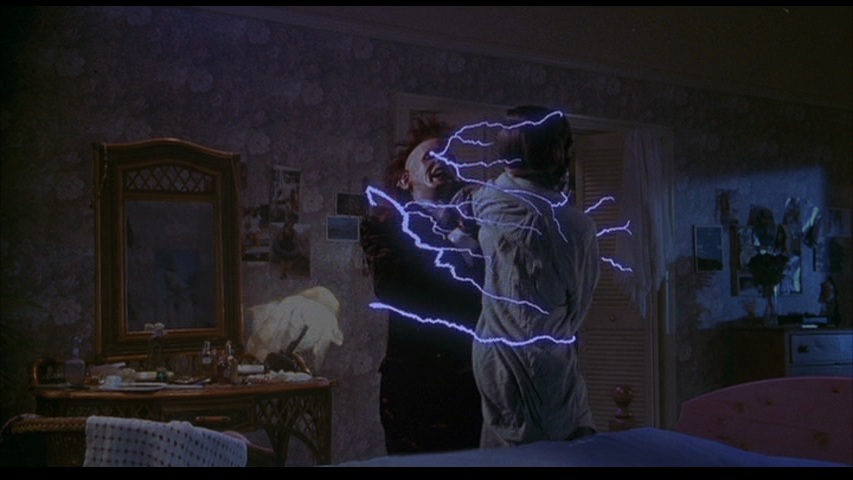

There’s a deleted scene that was to take place later in the film, with a confrontation between Michael, Trickster, and Kimberly that needs to be seen to be believed.

As animated lightning surrounds Michael and Trickster, the two characters merge together to form a horrendous, mess of a monster. A practical effects masterpiece that combines latex, animatronics, and puppeteering creates an abomination with multiple heads and limbs complete with moving mouths and tongues.

The end result of this complicated monster was a twisted creature worthy of Carpenter’s The Thing, grotesque and hypnotic nightmare fuel. Unfortunately, the effect was considered too different from the tone of the rest of the film and was cut. This was much to the disappointment of special effects make-up artists Steve Johnson, Andy Schoneberg, and especially Mike Smithson, who came up with the merged monster design.

It’s a shame that such an impressive piece of cinematic art was lost on the cutting room floor, but it’s worth seeking out the Blu-ray to see it for yourself.

Brainscan still resonates today because it’s about a lonely teenager hiding behind technology.

He sits alone in his room playing the Brainscan game instead of going to the party taking place right next door to his house. He films the girl across the street who he has a crush on instead of going over and talking to her. This scenario is eerily similar to so many of today’s teens (and adults), who live day to day behind the screens of their phones, detached from humanity and reality, both hating their reliance on their phone and unable to resist it at the same time.

Perhaps this conundrum is where Trickster exists, and perhaps Brainscan was too ahead of its time in 1994. But 2020 is definitely Trickster’s kind of world, which is exactly what makes it such a fascinating watch today.

Discover Brainscan for yourself. It’s available to rent for under $3 from Amazon and Vudu, or for $3.99 from Apple and Microsoft.

Follow Us!