On its 35th anniversary, we celebrate the legacy of “Akira” — a film that, to this day, remains impactful, thought-provoking, and powerful.

Like many, Akira was my gateway into the world of anime; back in the early nighties, anime was still very much unheard of — at least in the deepest, darkest part of South Wales, where I grew up.

My first encounter with Akira came via the cult corner section of MTV at the movies. After watching a three-minute clip and brief overview, the hunt was on to track down a copy. Fortunately, my wait wasn’t too long. A good friend of mine stumbled across a VHS copy, and so began my love of Akira.

Over the years, I have owned this film in almost every format it was released in, except for Laserdisc.

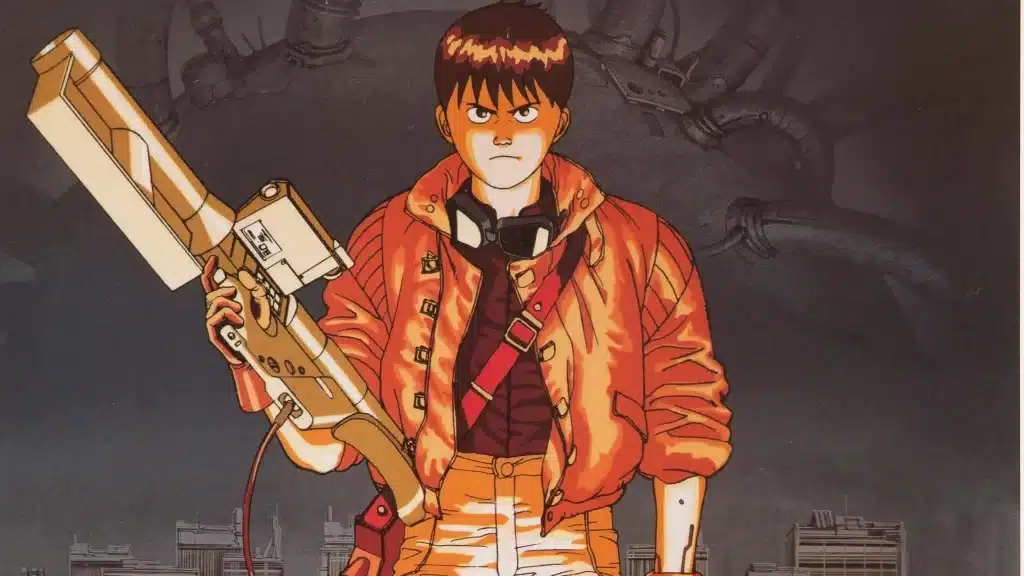

Akira began life as a manga created by the film’s writer and director, Katsuhiro Otomo. The story follows Shōtarō Kaneda, the leader of a biker gang who has grown up in the wake of a world war that saw the destruction of Tokyo. Part of the gang is his oldest friend, Tetsuo Shima, who, following a motorbike accident with an escaped government patient, develops telekinetic powers. That soon threatens to bring about the destruction of Neo-Tokyo and its inhabitants.

It’s all set against the backdrop of political upheaval and corruption.

What struck me on my first viewing and once again upon my most recent is the sheer scale of storytelling.

Akira is a multi-layered story pulling together cyberpunk, body horror, and a stark exploration of the lasting scares of nuclear devastation.

At times, this does lead to Akira becoming a little muddled and that final act becoming somewhat rushed. Interestingly, the manga ended two years after the release of the film. This gave Otomo the time and space to tie up this element of the story.

Despite its massive scale, Akira, at its heart, is the story of the breakdown of the nuclear family.

Both Kaneda and Tetsuo are orphans. Takashi, Masaru, and Kiyoko have been removed from their families. We, the audience, like these characters, are dwarfed by the monstrous size of Neo-Tokyo — a city raised from the nuclear ashes that has grown to become corrupt and dangerous.

It’s a place where biker gangs fight each other in running street battles, and new-age cults meld with anti-government protestors, all while bathed in perpetual neon lights and the overindulgence of consumerism.

Like the film’s young protagonists, the city has been abandoned by its political fathers.

Central to the film is the relationship between Kaneda and Tetsuo, two adolescent men on the cusp of adulthood but very much lost in a world with no real place for them.

Kaneda, on the surface, appears strong and confident and the leader of his gang. He has spent most of his life protecting and coming to the rescue of Tetsuo, who both loves and resents him.

In Tetsuo, the audience is given both a victim and an antagonist.

A young man going through destructive changes that he barely understands. Angry and resentful, Tetsuo is driven to try and prove himself, and time and time again comes up short.

One of the most heartbreaking scenes of Akira is when Tetsuo and his girlfriend Kaori are sat staring at the cityscape, dreaming of running away. However, their dream is brutally ended when a rival gang ambushes them resulting in Kaori being brutally beaten and almost certainly raped if not for Kaneda coming to the rescue and furthering his resentfulness towards his friend and fuelling his anger.

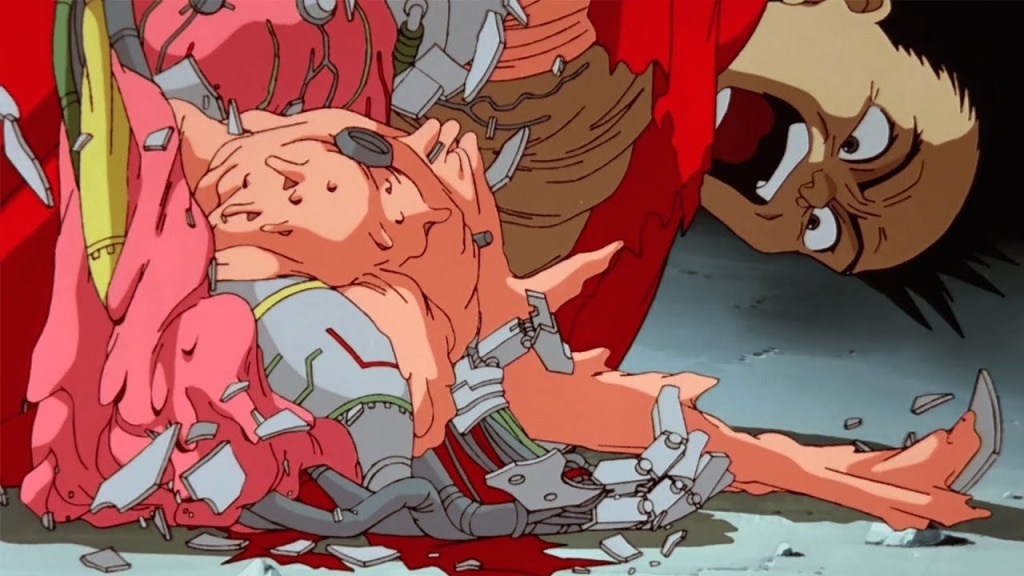

Tetsuo is the epitome of the angry young man, and his eventual horrific transformation is a not-so-subtle metaphor for the destructive nature of adolescence.

Or is it?

Professor of Japanese Literature and Culture Susan Napier writes in her book Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke that Tetsuo’s metamorphosis “represents a form of all-out adolescent resistance to an increasingly meaningless world in which oppressive authority figures administer the rules simply to continue in power.”

Akira is, without a shadow of a doubt, a stunning film to look at. Its animation is beautiful and flowing and, at times, even ethereal.

Unlike most other animated films, Akira was animated at twenty-four frames per second, an incredible feat given that Akira is hand-drawn.

They are combined with an incredible score that draws heavily from Indonesian Gamelan music. The opening scene depicts the first destruction of Tokyo and is played out in almost silence.

The smoothness of the destruction as a black dome mushroom outwards and engulfing all before is equally stunning as it is terrifying. The high angle of the camera as it moves down the street is one of the few times the city is seen in a state of helplessness.

Akira’s animation is in a class of its own when it comes to destruction.

The detail of that destruction is simply breathtaking, from the twinkling shards of broken glass flying as skyscrapers fall to the utter desperation etched across the faces of the inhabitants of Neo-Tokyo as they clamber for safety — while the very ground around them crumbles and slides into oblivion.

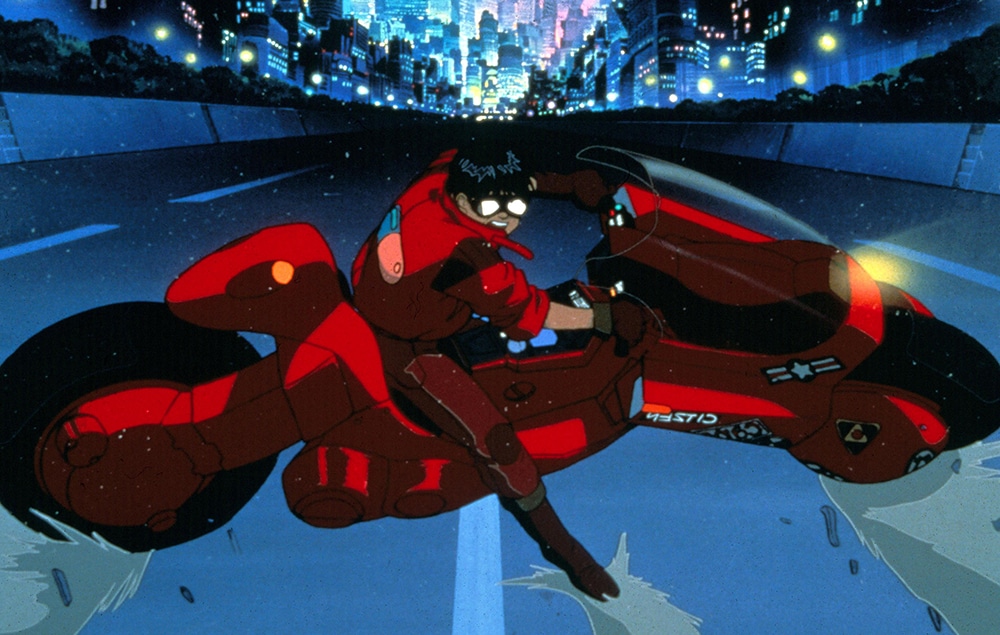

The action in Akira is blistering; the opening biker battle is iconic.

The low-angle camera movement glides through the neon-lit streets of Neo-Tokyo. As the new holographic gods of Japanese consumerism stare down at the population, a brutal gang war rages. One of the most striking images is the “Salary Man” trapped inside his car as the biker gangs rampage past. Smashing his windscreen and then launching a Molotov cocktail into his vehicle, it’s a reflection of a long-established cultural icon of Japan and a symbol of Japan’s post-war economic boom.

This transgressive explosion of violence all happens within the first opening six minutes of the film.

Andy Frain, following a viewing of Akira, was inspired to found Manga Entertainment in the UK.

In the book Sci-Fi Chronicles: A Visual History of the Galaxy’s Greatest Science Fiction by Guy Haley, he talks about its impact on him:

“I’d never seen anything like it. It was an animated Blade Runner, clearly not for children, but a well-crafted, thought-out, philosophical movie for grown-ups that happened to be in animation”.

AKIRA will be thirty-five years old this year and remains a true watershed moment in anime history. Click To TweetFor many of us of a particular generation, this was our introduction to a completely new genre. Akira kicked open the doors and paved the way for the golden age of anime that would run from the late 80s up until the 2000s. Films like Fists of the North Star (1986), Vampire Hunter D (1985), and Ghost in the Shell (1995) would make their way into the UK mainstream. The word Manga would become widely known, even if misunderstood.

As with any great film, Akira has had a significant impact on pop culture, from Kaneda’s icon red leather jacket to the pulsing body horror of Tetsuo’s transformation.

It’s a film that will continue to thrill and inspire generations for another thirty-five years.

Follow Us!