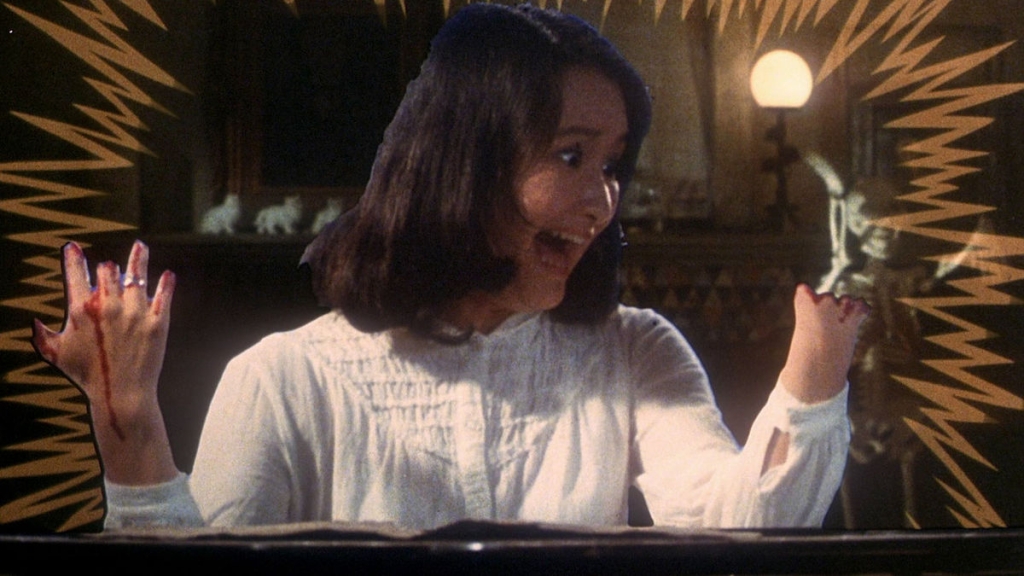

We celebrate 45 years of the wonderfully weird, indescribable, unforgettable Japanese experimental comedy-horror film “House” (aka Hausu).

When I was thinking about what to write for a piece about Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 film House, celebrating 45 years of entrancing and befuddling curious moviegoers, I found myself facing a crisis of conscience unlike any I’ve had writing about movies.

How do you begin to translate the experience of watching something as strange and singular as House into something as rigid and stuffy as the written word?

More than that, should you even attempt that in the first place? Wouldn’t it be better to just tell people to go out and watch it, preserving its surprises and delights? I think it would.

But alas, I’m bound by my solemn oath as someone who writes about movies (we’re all required to take it) to attempt to put something together at least.

That said, if you want to stop reading and go watch the movie first, I wouldn’t blame you.

If you want some idea of what you’re getting into before you watch, then, by all means, keep reading. If you’ve already seen it and your head is still spinning, then just know that I see you.

I can say without hyperbole that watching House remains one of my life’s most unforgettable cinematic experiences.

There is life before you watch it, and there is life after, and those two are in no way the same.

Am I hyping it up too much? Perhaps. But I will tell you this: the first time I watched the film many years ago, I couldn’t believe what I was viewing, eyes bulged out, jaw hanging open. The most recent time I watched it, in preparation for this article, I still couldn’t believe it, even if its oddest moments nowadays inspire more delighted cackles than open-mouthed disbelief.

It’s the sort of movie you just have to show other people, if for no other reason than to have someone else to talk to about it with, someone else to try and make sense of it. If you even can make sense of it. If you even should.

Have I sufficiently whetted your appetite? Alright then, let’s get into it.

Obayashi began his career making experimental films before finding a living in the world of advertising, and the brightly colored, overcaffeinated style of his commercials is on full display here. The genesis of House began when Toho, the film studio also responsible for the Godzilla films, approached Obayashi with the idea to capitalize on the success of 1975’s Jaws, hoping for their own blockbuster (the fact that this is what he came up with in regards to that assignment is absolutely incredible).

Inspired by conversations with his young daughter Chigumi, who came up with most of the movie’s setpieces, Obayashi developed the ideas into a film, handing script duties off to Chiho Katsura.

The film languished for two years, the concept so incomprehensible that no one at Toho wanted to direct it, but Obayashi was undeterred.

Eventually, Toho relented and let Obayashi take the reins as director, and the film finally saw the light of day in July of 1977.

Perhaps viewers at the time were even less prepared for the experience than we are today.

The film received largely negative reviews, though it did manage to bring in some money at the box office.

A movie like this is probably destined to be misunderstood in its own time, and true to form, House has grown a sizable cult following around the world, its charms proving more suited to the midnight movie crowd.

And truly, that might be the best way to experience a movie like House, which really is something you experience more than just watch.

Late at night in a darkened theater, possibly under the influence of psychoactive substances, surrounded by fellow intrepid moviegoers ready to dive into its bizarre and uncanny world. But really, any way you can experience this movie is worth it (the Criterion Collection had the good sense to include it, and you can currently watch it on HBO Max).

The characters of House are mostly teenage girls, each named after their one defining trait. Gorgeous is, well, gorgeous; Fantasy is a daydreamer; Prof is a smartypants; Sweet is a scaredy-cat; Kung Fu is tough; Melody is a musician, and Mac just loves to eat.

About to join her film composer father at their summer home for vacation, Gorgeous changes plans at the last minute when her dad reveals he’s brought a new woman home to fill the void left by her mother, who died eight years prior. So instead, Gorgeous invites her friends to come with her to her aunt’s house in the countryside, where she’s lived alone ever since her beloved fiance died in WWII, leaving her with only a furry cat named Blanche for company.

Once they get there, it doesn’t take long for weird stuff to start happening, and the girls disappear one by one as Auntie gets stronger with each disappearance.

The premise — high school girls vacation in a witch’s house — is incredibly simple, but it doesn’t even begin to prepare you for the actual experience of watching House.

Obayashi throws almost everything he can think of at the wall, bouncing madly from melodrama to whip-pan editing to animated interludes to delirious montage.

He utilizes his experience as a commercial director to give the film a deliberate sense of artifice, making liberal use of the green screens and clearly fake painted backdrops, drenching every frame in vivid colors.

On another level, it’s a movie drunk on the transportive power of movies, flinging from one genre to the next, whether it’s Fantasy’s Old Hollywood daydreams or an antic comedy starring the girls’ would-be chaperone, Mr. Togo.

It is, as you might imagine, a lot, its hyperkinetic visuals paired with a wall-to-wall score from Asei Kobayashi and Godiego that swings from acid rock to funk to classical and back again, shot through with an incessant piano melody that is sure to get stuck in your head forever by the end.

If there’s a larger point to be gleaned from House, I can see glimmers of a commentary on the changing world of postwar Japan and the expanding roles of women within that society.

In the decades after WWII and the devastation of the atom bomb, Japan was putting itself back together in a way that looked more Capitalist and, for lack of a better word, Westernized; Obayashi was a pioneer in a glossier, more hyperactive form of advertising, even bringing in Western celebrities to hawk Japanese goods.

In House, there’s a definite undercurrent of the changing ideals of femininity within this rapidly evolving landscape.

The girls, with their youthful vigor and hyper-romantic guilelessness, stand in stark contrast to Auntie, the personification of the lonely old maid figure who feeds off of their energy and youth.

Auntie can be seen as an embodiment of the prewar female archetype, endlessly waiting for her beloved soldier to return to fulfill her duties as a wife and mother, turned evil by being denied her destiny.

Though a product of a different time, the girls still have an old-fashioned sense of romanticism, remarking on how “manly” men used to be and, when things start to go south, still hoping Mr. Togo will come to their rescue.

Instead of a typical masculine hero, the men in House are completely bumbling and ineffectual, particularly Mr. Togo, who falls far short of Fantasy’s idealized vision of him.

In the end, the girls have no one but themselves, especially the highly capable Kung Fu, to try to find a way out of their predicament. Despite this, this is still a female-centered movie powered by the male gaze, its teenage characters shown in increasing states of undress, which adds an undeniably uncomfortable wrinkle to this whole interpretation.

Honestly, I have no idea if any of this commentary was intentional or if it’s the product of my critic’s mind trying to make sense of the nonsensical.

On a certain level, I feel that the inexplicable nature of the film is key to its continued power.

Even after repeated viewings, there’s something unknowable about Obayashi’s creation — a pop-art fantasia that mashes up traditional Japanese ghost stories, teen melodramas, and the encroaching influence of the West, throwing it all in a blender and splashing it with vivid colors.

To try too hard to ascribe meaning to it and justify every off-the-wall creative decision is to miss the movie’s point entirely.

It’s a cinematic experience like no other, one which retains its singular power 45 years later and will no doubt be around to puzzle and thrill for as long as there are eyeballs to take it in.

Follow Us!