These six shockingly subversive flicks may be less notorious than some well-known disturbing films, but they are no less noteworthy.

If curiosity ever gets the better of you, a simple Google search of the most disturbing films ever made produces some ghastly results, that is, if you’re green to the harder stuff. You’ll undoubtedly be met by countless lists rattling off the typical go-to selections. The more die-hard horror fans among you know which ones I’m referring to. You get Cannibal Holocaust, A Clockwork Orange, Audition, August Underground, and A Serbian Film — the usual suspects.

To most, the traditional selections are undeniably “disturbing.”

The sublimely shocking Cannibal Holocaust’s verité method still clobbers you, Audition’s lightning-strike jolts of limb-serving severity stabbing through the morose search for companionship are as disgusting as lapping up a dog bowl of vomit, and A Serbian Film puts in the overtime to make you scream “UNCLE!” And, let’s be frank, EVERYONE knows about Stanley Kubrick’s cult venture into the ultra-violence with A Clockwork Orange.

Digging deeper, these lists do tend to encompass the lesser-known films that rise to the challenge of attempting to make you pass out.

August Underground remains an unrivaled application of the found footage craze. Saló, or the 120 Days of Sodom, sits slightly outside the norm with its own brand of fecal ferociousness, and The Bunny Game has begun making more and more noise as the years tick by.

As we all know, labeling something as “disturbing” is subjective. What I find to be “disturbing” could be scoffed at by someone else. No one person’s nerves are flayed quite the same.

When taking on this list, the challenge was to find six films that don’t quite get the same attentiveness as, say, A Clockwork Orange or Cannibal Holocaust. There are plenty of films that wallow in oily black waters, which churn like a grotesque jacuzzi boiling their filth proudly. Instead, I opted to go for the slow-burns, the films you may pass by quietly on a streaming service or on a movie rack, unaware of the horrors they possess or the contemplation they inspire.

Are there more? You bet there are.

So, I leave you with six flicks I have painstakingly chosen that I feel live up tremendously to the disturbing films label. I feel as though they are far from the typical, the obvious. I believe each and every one will put you to the test, haunting you like a ghost long after they have faded to black.

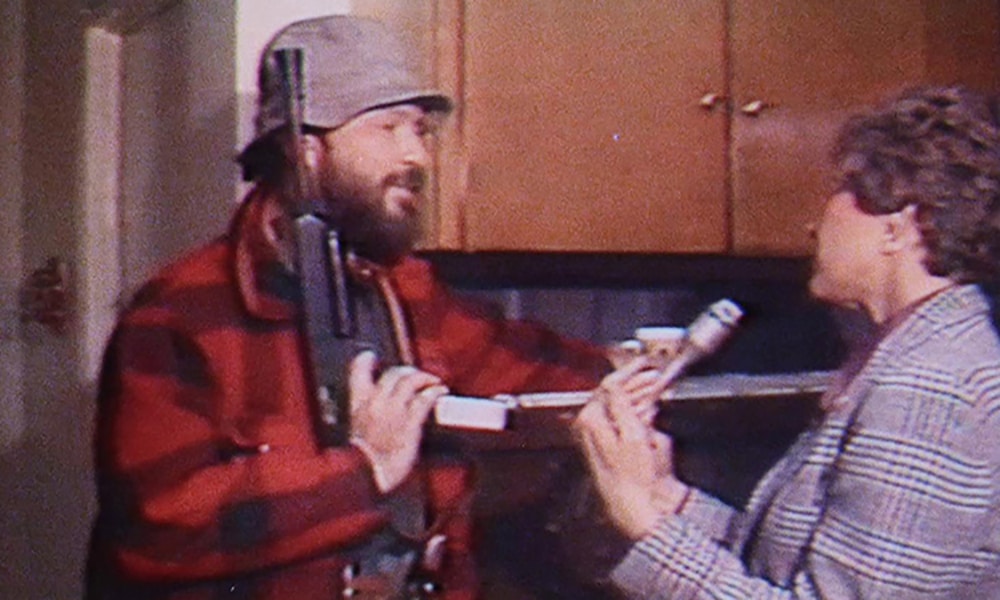

1. The Killing of America (1981)

What is it?

A rare, hair-raising 1981 American-Japanese “mondo” documentary directed by Sheldon Renan and written by Leonard and Chieko Schrader, it was meant to focus on the growing epidemic of gun violence gripping America.

Why is it Here?

Failing to secure a proper distribution in the States, largely forgotten and stamped out for years, The Killing of America unearths nearly two decades’ worth of violence captured on camera, beginning with the shocking 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy captured by Abraham Zapruder.

From there, it’s an unending barrage of serial killers, mass shootings, suicides, homicides, and countless other atrocities that blister your brain matter, all set to a gritty narration from Chuck Riley, who walks you through grisly footage as if his soul climbed out of his body and onto the cold slab of a morgue.

Possessing almost zero levity throughout its hour-and-a-half runtime, The Killing of America is a storm cloud of celluloid, one that drove several of those who worked on it into depression. So overwhelmingly sullen is the experience that the filmmakers were even forced to lighten things up by tacking on footage of John Lennon’s memorial as a means of offering some semblance of optimism.

The Verdict:

The Killing of America is one of the most depressing and haunting movies I have ever seen. Period.

I’ve waded through some brutal shock reels over the years, and The Killing of America may rank as the heaviest, almost to the point that this sucker must be made of concrete. It dolls out haymaker after haymaker to both your stomach and your senses, leaving you bruised, battered, nauseated, and stricken with a total disdain for mankind.

It’s found even more chilling relevance in modern times, with Severin Films rescuing the film from obscurity in 2016 and unleashing it upon a nation brought to its knees by wave after wave of mass shootings that continue to dominate the headlines.

You’ve been warned: The Killing of America stands as the doom-and-gloom champion of the “mondo” shock-docs, a powder keg of hopelessness that will burn into your every fiber.

2. The Piano Teacher (2002)

What is it?

Based on the controversial book of the same name by Elfriede Jelinek, this is writer/director Michael Haneke’s voyeuristic glimpse into the sexual repression of a frigid piano professor at the Vienna Music Conservatory, who enters into an increasingly tumultuous relationship with a charismatic student.

Why is it Here?

Nabbing the prestigious Grand Prix award at the Cannes Film Festival in 2001, arthouse darling Michael Haneke’s unflinching peek into the lonely life of Erika Kohut may not seem like an obvious choice to make this list. Haneke, who is no stranger to crafting provocative works of art, delivers a film that is not marred in scandal or the subject of heavy edits or outcries.

Instead, he quietly plucks the keys of a character played with astounding vehemence by Isabelle Huppert, who presents herself as a fiercely standoffish instructor who harbors a pitch-black side that discharges in inconceivable ways.

She is callous to her students; she spends her nights visiting neon sex shops, mutilating her genitals with razors, and spying on couples having sex at drive-ins.

And that is only a sliver of what transpires in The Piano Teacher, with Erika’s sadomasochist tendencies emerging with fury once she meets Walter Klemmer, the handsome young student who adamantly pursues her.

The Verdict:

Let me start by saying that I know The Piano Teacher is a peculiar choice for this list. For the unaware, they may queue this movie up on Max and quickly think, “What the hell is that guy smoking?!” Stick with it, as the notoriously devious Haneke hands you a ticking time bomb.

It’s a portrait of an individual wedged between her esteemed image and career in the fine arts and an insatiable sexual appetite that is growing more poisonous by the day.

Erika is like a shattered shard of glass, shimmering with beauty but ultimately fractured into fragments sharp enough to cut through your fingers. Huppert gives a career-defining performance, terrifying and enigmatic as she grapples with her desire for the charming and talented Walter, adding uncomfortably raw power to her sexual encounters that spell certain doom, and that doesn’t even include the cruel stunts she inflicts upon her students.

By the time the curtain closes on this self-destructive recital, you’ll be left picking your jaw up off the floor and stammering, “Oh, now I know why that guy dared me to watch this…”

3. Maniac (2012)

What is it?

Arriving at the tail end of the horror remake cycle that kicked off in the early 2000s, Maniac is a septically shrewd re-imaging of the grimy 1980 grindhouse classic of the same name that starred cult figure Joe Spinell as a serial killer stalking the streets of New York City.

Why is it Here?

Penned by Alexandre Aja and Grégory Levasseur and directed by Franck Khalfoun, Manaic 2012 is a bracing revamp of William Lustig’s controversial cult shocker that boasts a “New Extremity” edge that instantly sets it apart from the pack of other horror remakes.

Yanking the tale of Frank, a schizophrenic who preys on young women, off the mean streets of 1980s New York and dropping it into seedy avenues of present-day Los Angeles, Maniac 2012 becomes a nigh immersive experience as it wedges you into the work boots of our deranged serial killer, viewing the proceeding behind his eyes.

The results of this experiment, which seem inspired by the rising popularity of “found footage” films, open the floodgates for a sense of dread that many other slasher films fail to capture.

The film smartly makes you the madman, ending up a taxing examination of the slasher film and the audience’s enthusiasm for the violent kills that made the subgenre such a hit.

The Verdict:

Spiffier and splashier than Lustig’s guerilla-style hellscape of “Fear City,” Maniac 2012 was a grotesque spin on a film that was already pretty damned disturbing.

And while some of the acting reeks of being rehearsed, Elijah Wood’s skittish rendering of a serial killer who falls for a beautiful artist will leave you contorting in your seat.

With Khalfoun forcing the knife into your hand and guiding it into quivering flesh, Maniac 2012 pushes you into the warzone that is a serial killer’s mind and, in the process, becomes something more than a simple psychological study.

Upon a rewatch, I couldn’t help but think about America’s current fascination with true crime and serial killers, which are becoming more and more glorified with each passing Netflix series.

Our morbid curiosity is put to the test, with Khalfoun dousing us in a thinner that strips away the curiosity and amplifies the morbid to an excruciating decimal.

4. Elephant (2003)

What is it?

The controversial second entry in director Gus Van Sant’s “Death” trilogy, this shocker nabbed the Palm d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and used the Columbine school shooting as its terrifying subject matter.

Why is it Here?

Arriving four years after the appalling Colorado high school shooting that left thirteen dead (not including the perpetrators), Van Sant’s fly-on-the-wall staging of a normal day at an ordinary high school that descends into a bullet-riddled firestorm left audiences dazed.

To this day, it remains an alienated meditation on the horrors of that April day.

As time has gone on, Elephant has remained an oddity, one that even acted as a catalyst for a copycat school shooting in Red Lake, Minnesota, making it all the more frightening. Even more noteworthy is the title, which Van Sant has said refers to a Chinese proverb of several blind men touching different sections of an elephant, which leads each of the men to arrive at different conclusions about what they have touched.

It’s also been said that the film’s title refers to “the elephant in the room” (Where were the parents? Were there warning signs?).

Whatever conclusion you draw from Elephant, it’s almost universal that the film’s impending descent into bloody mayhem will buckle your knees.

The Verdict:

Given that the actions of the perpetrators of the Columbine shooting have been exhaustingly analyzed by everyone with a fancy psychology degree and anyone sitting at a news desk, Van Sant’s application of the Chinese proverb is a singed bullseye.

Everyone has their own take on what sparked that awful tragedy, from bullying to movies, all the way to heavy metal, the convenient boogeymen of the academic institution, and irresponsible parents who reject responsibility for their own children.

What is even more tragic is that the film continues to resonate, as countless other school shootings – and mass shootings, for that matter – have continued to plague us with little in the way of action or elucidation.

As for Van Sant’s lucid slant, which tracks several students drifting like clouds with routine robotism inside a shell that is supposed to pledge safety for our future, he stages an unfolding tragedy in the exact manner with which any active shooter situation could arise – casually and suddenly, with a precision that barely allows you to process the severity of the situation until it’s far too late.

As Van Sant closes on a semi-burning school screaming in sirens, with a father and his son locked in a shell-shocked stare, he unknowingly presents to us the birth of the American apocalypse, devoid of any trace of cinematic glamorization or artificial dramatization that resists allowing you the comfort of knowing it’s only a movie.

5. Fat Girl (2001)

What is it?

A 2001 arthouse drama from celebrated director Catherine Breillat, Fat Girl is an unblinking story centered around two teenage sisters who are coming to terms with their budding sexuality, which culminates in a lurid encounter.

Why is it Here?

Shrouded in controversy, initially banned in Canada for its unflinching portrayal of graphic sexuality involving teenagers (it was eventually overturned), and coming under fire in the UK for a climatic rape sequence that is dreadfully distressing to watch, Fat Girl is the type of film that makes you so uncomfortable, you desperately want to shed your own skin like a snake, crawl under your couch, and hide your face for hours.

Following Anaïs and her older sister, Elena, who are on vacation with their seemingly wealthy parents, the two happen upon a handsome law student, Fernando, who is instantly smitten with Elena. As Elena and Fernando quickly become physical, the two siblings bicker about their budding sexuality, their “first time,” and quarrel as all sisters do.

Breillat’s static camera lingers on graphic sexual exploits, sure to drive a good chunk of viewers to pause the movie in outright disbelief, but that is nothing compared to the final frames of Breillat’s unyielding masterwork.

It ends up generating dialogue about the sacred nature of sex, the fragility of our relationships, the naivety and manipulating dynamisms that circle around us, and, much like Elephant, the swift advent of violence and coming to terms with our mortality.

The Verdict:

One of the finest efforts of Breillat’s career, which is loaded with polarizing entries that never fail to initiate a discussion, Fat Girl is superbly acted, directed, written, and paced, with the emotionally draining conclusion flattening you like a steamroller.

It helps that Breillat harbors so much confidence in her leads, Anaïs Reboux and Roxane Mesquida, who give an electric tenuousness to their sisterhood, which swings like a guillotine between affectionate and bruising.

And while there is a sliver of humor nestled into pockets of Fat Girl, Breillat expectedly shies away from sugarcoating the pains of growing up as a majority of coming-of-age films do; it’s the unapologetic intimacy laid bare, condom and all, that allows Fat Girl to bash us across the face with an axe.

We are warned to abandon all hope, ye who enter those cavernous recesses of young adulthood, as what awaits us is strained relationships, heartaches, teary-eyed quarrels, and the waiting embrace of the grim reaper, who has quietly been bottling all the energies of this trying world.

When Breillat closes upon a freeze frame sure to halt the blood coursing through your veins, she is capturing the last vestiges of innocence, leaving the body like a spirit entering the void.

6. The Damned (1969)

What is it?

Italian director Luchino Visconti’s diabolical 1969 epic of a wealthy German industrialist family during the rise of Fascism would act as one of the main inspirations for the “Nazisploitation” subgenre that would dot grindhouse theaters throughout the 1970s.

Why is it Here?

Arriving a few short years before infamous disturbing films Saló, or the 120 Days of Sodom, Salon Kitty, and Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS, Visconti’s melodramatic waltz with perversion and corruption festering as an infected sore inside the jackbooted Third Reich goosestepped decadently across screens to critical acclaim.

It also had many rating board suits nervously tugging at their sweaty collars as they beheld a flurry of explicit sexuality and gory cruelty packed neatly into a story based on the Krupp family, who kept the Nazi war machine supplied with a wide array of weapons and ammunition.

As one of the films that laid the groundwork for the highly controversial “Nazisploitation” subgenre that found success during the mid-1970s, which gorged on a steady diet of greasy excesses and leather-clad sadomasochism branded with the ultimate symbol of evil – the swastika — The Damned remains one of the most shocking,

It is armed with an alarming realism that plays an anguishing hand of horrors – mass murder, incest, pedophilia, suicide – that allows the bite of Essenbeck’s scheming to land like the snapping jaws of a rabid wolf.

The Verdict:

Simply put, The Damned is a film any serious film student should seek out.

It’s a testament to Visconti’s boundless talents as a filmmaker, and it possesses some of the most handsome cinematography I’ve ever seen — a chiaroscuro gift from cameramen Pasqualino De Santis and Armando Nannuzi.

The compositions resemble the flowing elegance of a Renaissance painting clad in fish nets and wielding a smoking machine gun.

And yet, through all its flair, The Damned is a terrifying example of the acidic erosion of rampant corruption, using the Essenbecks as a way of mirroring the meteoric rise and flailing freefall of Nazi Germany through a sickly swamp of unconstrained depravity.

And who is the king of this swamp but Martin Essenbeck, the pedophilic heir to the family business, played with exploding fury in a breakout role by Helmut Berger, who nabs the film’s most iconic sequence.

While the politicking is certainly high in The Damned, the film’s ruthlessness in appalling you is just as savage as the legions of shadowy SS officers carrying out the bloody slayings of the SA in the “Night of the Long Knives” massacre. And while the bullet-riddled human wreckage quotient is met by the bucket, the carnage directive culminates with Essenbeck’s ultimate implosion, manifesting in the climatic rape sequence between Martin and his aloof mother.

You’ll be left begging for mercy, but Visconti drives the black boot down as hard as he can on your windpipe.

Follow Us!