2010’s “Motion Sickness” is a little-known surrealist nightmare and allegory for the Jewish experience that deserves an audience.

I wasn’t planning on writing about two deeply confounding 2010 movies in a row, but such is the way the Tubi gods led me this time. This one is a different flavor of weird from my previous Tubi pick, Maximum Shame, but it might be just as impenetrable in its own way.

Motion Sickness, the second and (to date) final feature film by S.M. Kerstein, seems to have flown almost completely under the radar. Other than an official website featuring a little bit of information, there doesn’t seem to be much out there about it online; a Google search is more likely to turn up articles about movies that physically make people motion-sick than about the actual film.

Despite a few festival appearances, its distributor appears to be defunct, leaving it one of many lost souls in Tubi’s vast library. But does it deserve such an ignoble fate?

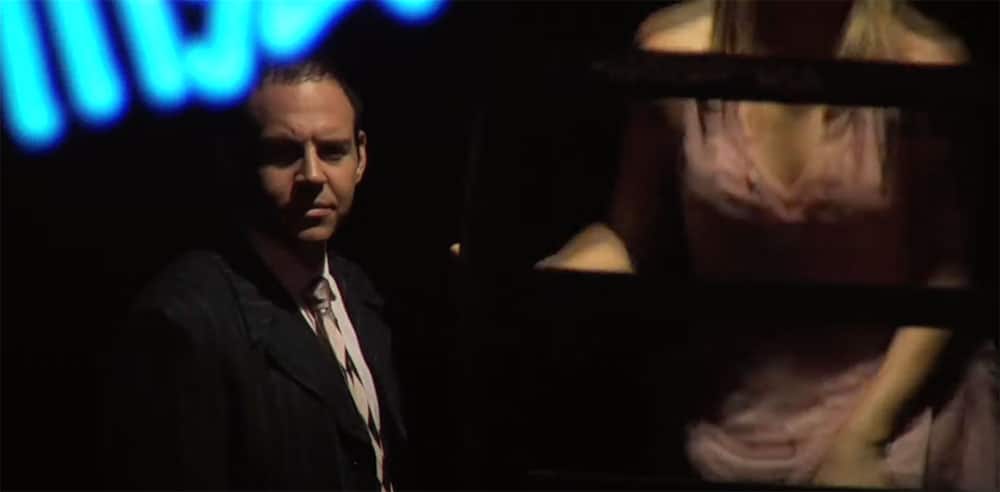

Billed as a “surrealist noir,” Motion Sickness owes a clear debt to the king of such movies, David Lynch — Mulholland Drive, in particular.

It cribs a few of that movie’s well-known signifiers, from a secret after-hours club to a mysterious box that completely shifts the narrative halfway through, as well as its fascination with twisting noir tropes and a sense of vague unease.

I’m not trying to accuse it of plagiarizing or anything, but the similarities are definitely apparent.

What sets Motion Sickness apart is its uniquely Jewish perspective, which is uncommon in movies like this.

Two detectives (Jimmy King and Elena McGhee) investigate a headless corpse found on a river bank. In its pocket is a wallet containing two IDs: one for Shem Mochin (Jason Liebman), a former rabbinical student and scholar, and one for Aver Noga (Trevor Nelson), who is…just some guy. Does the body belong to one of these men? If so, which one? Could it somehow, improbably, be both?

Cut to Shem, living a solitary existence studying the Torah in his apartment; his only friendly acquaintance is with the building’s super (Neil Levine), who keeps digging holes in the yard for unknown reasons.

He’s dealing with an inexplicable paralysis in his leg with no obvious medical cause, leading his chummy doctor friend Bentzi (Simon Fell) to deduce that it may be psychological in nature.

Accepting an invitation to the aforementioned mysterious after-hours club sends Shem tumbling down a rabbit hole of guilt, fear, and paranoia, descending into a nightmare and waking up as Aver in one of the super’s backyard holes.

Living in the same apartment, Aver is dating the super’s niece, Tiferet (Cecile Monteyne), but we don’t learn much about him otherwise.

One day, he’s attacked in the building by a hostile vagrant (Musto Pelinkovicci) who makes off with his apartment keys. Left with a bleeding head injury, Aver begins experiencing strange visions conflating sex with medical experimentation, along with visions of himself as a former rabbinical student named Shem.

Confused? That’s probably by design.

Motion Sickness operates with the logic of one of those dreams where you’re somehow both yourself and a completely different person, both acting out the dream and watching it unfold from a distance.

The filmmaking accentuates this uncanny feeling, with jarring sound design and performances directed like they’re straight out of the 1930s.

It’s a slippery sort of movie, one where we’re left to constantly question what’s real. Like a particularly eerie dream, it resists easy analysis.

I could be reaching for this interpretation, but many of the symbols in Motion Sickness seem to be pulled straight from the subconscious fears of the Jewish people in the post-Holocaust world.

As a gentile, I can’t speak to its depiction of the Jewish experience, but certain images can’t help but conjure that horrible time in our public imagination: barking German Shepherds, holes reminiscent of hastily dug mass graves, non-consensual medical experiments, a train official aggressively demanding to see “papers.”

Even the train itself is used to unsettling effect, its chugging motion a reminder of the rails that brought millions of Jews to their deaths.

Shem and Aver seem to represent two sides of Jewish identity: one devout, one lapsed. On some level, perhaps Kerstein is examining what it means to be Jewish in the modern world, where the psychic scars of past traumas are still very present and the threat of violence never too far away.

Like its most obvious influences, Motion Sickness is bound to be polarizing, intriguing some and alienating others.

While it’s at times derivative and a touch overlong, it’s still a striking film and one that I think deserves more attention than it’s had.

Follow Us!