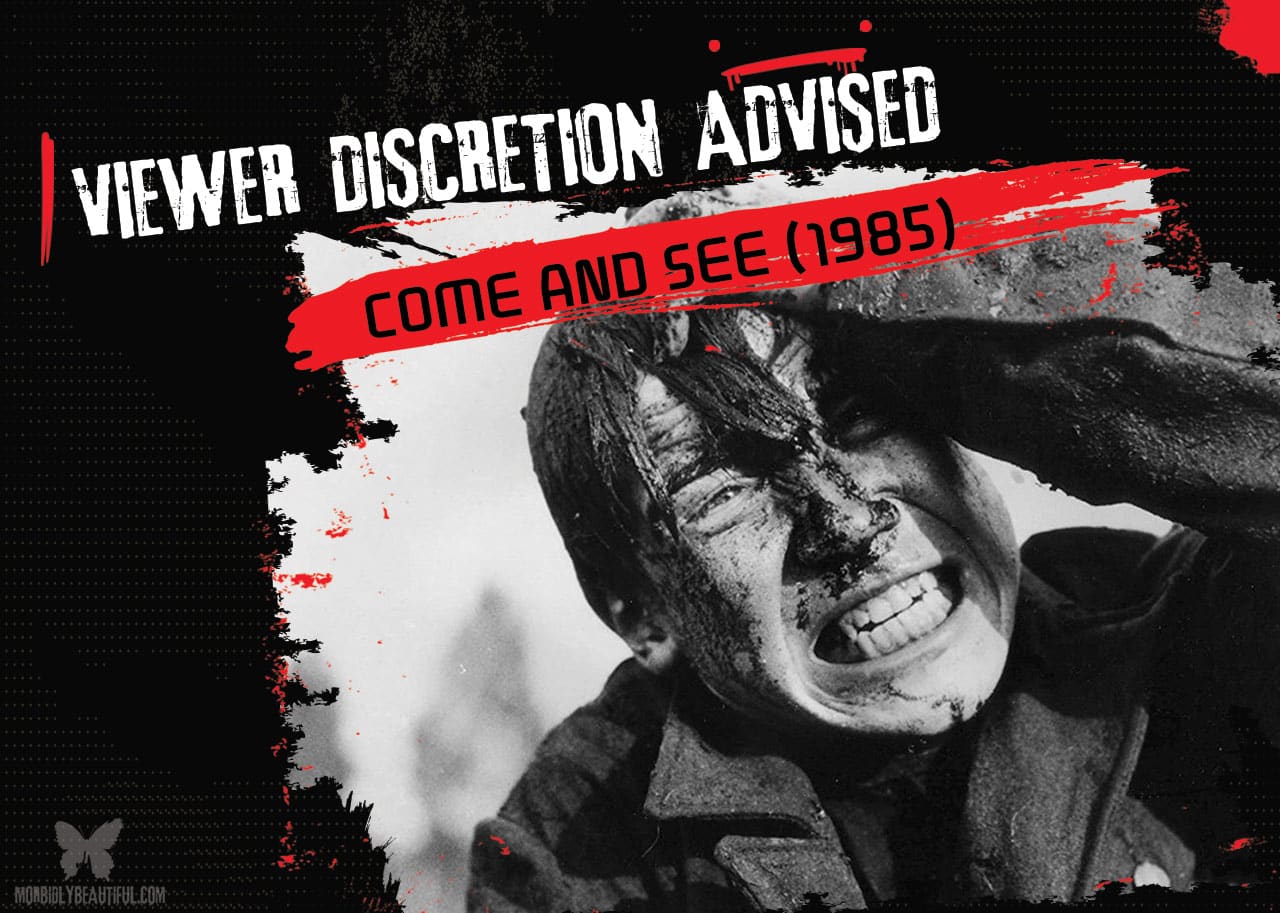

A brilliant and punishing portrayal of the horrors of war, the likes of which you’ve never seen, “Come and See” leaves you forever changed.

COME AND SEE (1985)

THE PLOT:

Picking up in 1943 Belarus, young Flyora (played by Aleksey Kravchenko) dreams of joining the Soviet resistance and fighting back against the invading Nazis. After finally getting his wish, Flyora is initially saddled with mundane tasks at a relatively safe outpost nestled in the dense nearby forests. After finding himself ordered to stay behind with a beautiful nurse, Glasha (played by Olga Mironova), the two strike up a budding relationship that is interrupted by the German forces, casting them into an apocalyptic conflict where unimaginable horrors await.

THE BLOODY BACKGROUND:

The final film from Soviet director Elem Klimov, 1985’s Come and See was written by Klimov and Ales Adamovich, who served in the Belarusian resistance during WWII and would go on to write two novellas, “Khatyn” and “I am from the Fiery Village,” which provided first-hand accounts of the horrifying human atrocities that took place during the conflict.

After languishing for eight years in front of the USSR State Committee for Cinematography due to the film’s gruesome subject matter under the working title of Kill Hitler, Come and See was finally granted permission to begin production in its entirety, emerging as what many consider to be the most harrowing anti-war film in existence.

THE DAMN DIRTY DETAILS:

Debuting at the 14th Moscow International Film Festival, Come and See would see a theatrical release three short months later and be met with widespread critical acclaim.

As the years have passed, Come and See has continued to be showered with acclaim, with many contemporary critics and casual viewers agreeing that Klimov’s magnum opus is resoundingly the finest war film ever made. There is also a general consensus that it’s one of the most disturbing depictions of war you may ever see, with the film possessing a bone-chilling realism that simultaneously mesmerizes and terrifies with each passing second.

Crafted for maximum authenticity, Klimov used non-professional actors and actresses and even went so far as to use live ammunition in certain sequences, a startingly omission that was confirmed by star Kravchenko, whom Klimov also tried to hypnotize during filming so that the teenager would not remember some of the more emotionally taxing moments of the production. The director was unsuccessful with this tactic, leaving Kravchenko skipping back to school with a head full of gray hair once a wrap was called.

In the wake of its release, Klimov has claimed in interviews that ambulances stood at the ready outside of various theaters so that they would be prepared if sensitive audience members needed immediate medical attention during the showings.

So profound is the impact of Come and See, the Criterion Collection released a handsome restoration of Klimov’s film on Blu-ray in 2020, which once again thrust the film into modern conversation and preserved the film’s organic eminence.

THE HORRIFYING TRUTH:

Without a doubt, by the time Klimov closes the curtains on Come and See with a barrage of stock footage comprised of Adolf Hitler and the unconceivable number of atrocities his Nazi regime instigated, even the most hardened horror viewer is going to find it downright impossible to walk away unaffected by what they have just seen.

Opening with a surrealism that bobs between vaguely crude and hazily dreamlike, Come and See drifts like a cloud into a gathering storm, which morphs into a frazzled nightmare that rains down a fury of anguish that claws at you like one of the terrified refugees being driven from their homes by the goosestepping Germans that pour through the quaint villages with an insatiable bloodlust.

Of course, the taxing pace is mirrored in our young protagonist, who is cast into a hell that he couldn’t possibly have conceived through the rose-colored glasses of his chubby-cheeked naivety.

Our awakening begins on a sandy beach where Flyora and another boy play amongst the contorted remains of dead soldiers, with their town elder cursing them for their deed. Ah, but boys will be boys, and what young boy hasn’t occasionally lost themselves to playing make-believe war? It’s natural, only here, that they dig for ACTUAL weapons and mimic the raspy commands of German officers.

It’s innocuous role-playing, at least until a Focke-Wulf Fw 189 Uhu comes rumbling overhead, a grim omen that silently warns us we will be witnesses to sublime cruelty we are powerless to prevent.

So, come and see…

Of course, the arrival of the reconnaissance plane is a signal that this is not a playful romp along a scenic shore.

Abandon the removed safety of a glossy Hollywood production, where quick cuts and chest-pounding heroics allow the bitter veracities to go down easier.

Much like Flyora, you’re unprepared for the horrors that are lurking just outside his village. I was. You will be, too.

Come and See is THAT extreme of a depiction, to the point that it transcends simply being a motion picture and transforms into a dirt-caked relic that has been buried like a spent shell casing.

Perhaps it’s a blessing that Come and See rejects refinement, considering that we often times romanticize the events of WWII and, even to this day, find ourselves plagued with far-right clusters that idolize the devastating rhetoric of Hitler. Maybe they should gather ‘round for a viewing of Come and See. Perhaps they’d question their erroneous politics and realize the error of their ways. And maybe our veterans wouldn’t be rolling in their graves.

The violence within Come and See isn’t quite as overstressed as it was in something like Saving Private Ryan.

Sure, Saving Private Ryan back-handed you with its limb-severing carnage of D-Day, but its quick cuts, Tom Hanks’ star power and adrenalized slant kept you safe with the assurance that, to quote the trailer of The Last House on the Left, “It’s only a movie… it’s only a movie.” Still, you have to hand it to Spielberg for at least attempting to toss you into the puke-smeared U-Boats, where men prayed into overcast skies, kissed the crosses around their necks, and ultimately, came to the horrifying realization that those helmets plunked on their heads did very little to shield them from the onslaught of white-hot lead cutting through the air.

Yet for all the explosive action of Spielberg’s sobering classic, COME AND SEE favored slowly lowering you through the seven circles of hell.

At first, what carnage we do glimpse is fleeting, with bodies piled up behind a house or a severely burned man whispering of the torment the Germans put him through. The violence is often implied, etched into the soot-stained faces of the innocents uprooted from their homes and cast adrift into a charred and smoldering countryside robbed of its tranquility.

It’s so dense; just the pain in the eyes of the souls put in front of us is enough to snap your soul to bits.

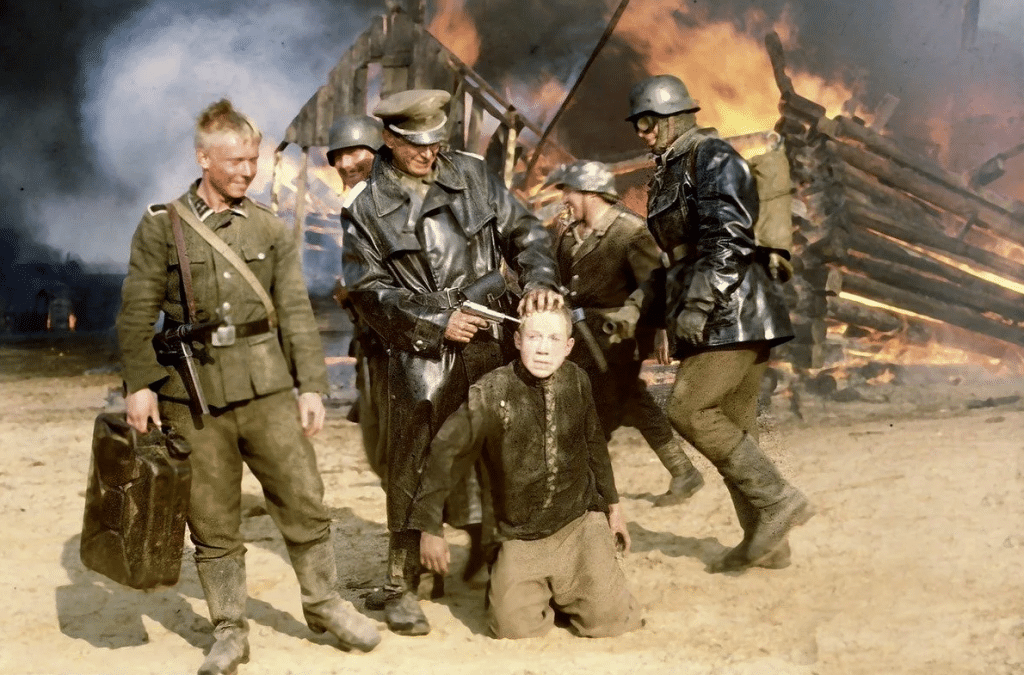

As Klimov trudges through this dreamscape of pain, he arrives at a final destination that could rank among the most traumatic sequences in motion picture history. Young Flyora ends up in Perekhody, a town besieged by an SS Einsatzkommando unit, who quickly rounds up the villagers and forces them inside a church, which is then perforated with bullets and set ablaze.

It’s perhaps one of the most punishing pieces of cinema I’ve ever laid eyes on, and it’s accomplished with such a heightened sense of practicality that you’d swear it wasn’t staged at all.

And all this death is monitored by drunken soldiers who suck on crab meat, humiliate the handful of survivors they allowed to flee the structure, and even pounce on one poor woman, who is then gang-raped and sent stumbling away with a whistle lodged in her bloodied lip.

By the time Klimov is ready to shake us from this fevered dream, he closes on Flyora, now nearly unrecognizable under jagged gray hair and tearful wrinkles, firing his rifle into a picture of Adolf Hitler, with each bullet setting off a flurry of stock footage played in reverse.

What emerges is a skittish collection of black-and-white newsreels featuring grisly glances of the Holocaust, exploding bombs, cheering Germans, and a beaming Fuhrer all being erased from history, with the final image being that of an infant Hitler held by his mother.

What if Hitler had never grown into the mad dictator he became? It’s a question that slams into your chest like a hurtling wrecking ball, leaving you crumpled into a heap of ruin.

And as we fade to black and you’re left with a thousand-yard stare akin to the one stamped onto Flyora’s face, as powerless as a droning aircraft peering down from a sky poisoned by ash and flame, you’ll be a firm believer in the power that Come and See possesses.

You’ll also realize that Klimov has gently nudged you into one of the seats of that reconnaissance plane with a duty to pass along a critical message to the world beyond the screen: war is hell.

Follow Us!