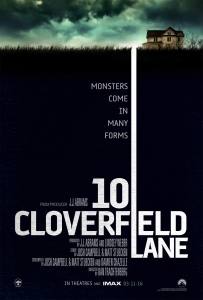

I Think We’re Alone Now: An Analysis of the Important Themes of Femininity, Masculinity, and the Female Experience Explored in “10 Cloverfield Lane”

Editor’s note: The following is an in-depth analysis of the deeper meanings contained within 10 Cloverfield Lane. As a result, there will be significant plot spoilers discussed. If do not wish to have anything spoiled, please do not read the following until after you have watched the film.

Not long after the release of 10 Cloverfield Lane, there was conversation on how to categorize it and whether it falls into the category of horror. There were, of course, resounding dismissals that the movie was not really a horror film. This is a discussion one usually sees in the horror community following the release of certain intelligent and thought-provoking films — to the point that the question seems trite and a way to obfuscate obvious horror components in various media.

However, to dismiss 10 Cloverfield Lane’s inclusion into the horror canon is to dismiss the valid female terror depicted onscreen and the reflection of society that is contained within the taut 104 minute movie.

The film is undoubtedly a work of art, from its direction to its acting, cinematography, and score. The elements in this film are delicately wrought, and because of this the overall effect the movie has is more terrifying.

10 Cloverfield Lane is very literally a contained film. The majority of the action and the drama takes place in the bunker, except for the very beginning and the very ending of the movie. The bunker serves as a societal microscope where the female experience is magnified via Michelle (played by Mary Elizabeth Winstead.) If you stripped away all the fantastical trappings of the situation and the character of Emmett (played by John Gallagher, Jr.), you would have a story that could have been ripped from newspaper headlines.

10 Cloverfield Lane could have easily veered into a fairly standard theatrical true crime rip off instead of a layered narrative that truthfully gives insight into the horrific elements of the female experience.

After Michelle’s car wreck that takes place after she flees her flat, and ultimately her problems with her fiancé, she wakes up chained in a cinderblock room, her pants removed, and her leg in a brace. Her cell phone has no service. She is understandably confused and frightened. We are then introduced to Howard, who from the start takes a stern and commanding tone with her. Michelle’s innate ingenuity is shown from the start, letting us know that Michelle herself is a force to be reckoned with.

Women in the real world have to stay constantly vigilant. Trusting men can be a risk in and of itself. There have been countless cases of women being abducted and held captive by men for years before they either escape or are killed. Even men who are seemingly nice can pose a threat. How many serial killers have used their charm to disarm women and make them comfortable before horrifically murdering them? On a basic level the film deals with a real world problem women face and thus renders horror from it.

From the moment the viewer meets Howard (played by John Goodman), they are thrown into a limbo of doubt and questioning. Is he really the savior that he presents himself to be? Or is he a nefarious person who is manipulating Michelle for his own gain and expecting her to be thankful for “saving” her? From the start, one thing is certain: Howard has a strict sense of entitlement. He makes a comment that Michelle needs to show him some appreciation. I mean after all, he did save her life, didn’t he?

He takes offense to her healthy skepticism and is invasive with Michelle, all in the name of not being able to trust her. Howard turns into a beacon of toxic masculinity almost immediately. He acts as if Michelle owes him her unwavering trust automatically just because he supposedly saved her life not only from a wreck but from some unclear deadly cosmic event.

He tries to eke loyalty out of Michelle at every possible opportunity, including showing her his pigs who have died violent deaths because of the aforementioned cosmic event. He lies to Michelle about the true origin of her wreck by admitting that he did cause it, but it was just the result of him speeding while trying to get home after the start of the mysterious event that drove them all to bunker.

He is manipulative, petulant, jealous, and condescending. He is always quick to remind Michelle and Emmett that they should be grateful to him. Michelle is not so much a person to him as she is an object. She’s merely a possession, something for him to control. The viewer confers that his possessive, controlling, and obsessive behavior is the root of why his wife divorced him and packed up their daughter Megan — exiting the picture long before the intersection of Michelle and Howard’s lives.

Howard tries to impress what he perceived as important parts of Megan’s personality on to Michelle. During the uncomfortable first dinner together, he makes a comment about how Megan loved to cook and that Michelle will learn to love to cook also. Howard is undeniably predatory and intimidating, know matter how much he tries to drive home that he was a loving father and a generous and sensible man.

Emmett functions as a foil to Howard. When we first meet Emmett, he comes off as a genuinely well-meaning guy. However, at first, Michelle has reason to be wary of him. Just because a guy appears to be nice doesn’t mean that he actually is nice. Michelle approaches both Howard and Emmett with skepticism, not knowing who or what to trust in her bizarre situation. Emmett helps serve as confirmation that something catastrophic happened and that it sent him running to Howard’s bunker that he was hired to help build years earlier.

As 10 Cloverfield Lane progresses, we get a better glimpse of Emmett’s character and how he proves himself to be an ally to Michelle and her only true friend in the bunker.

Emmett has all the trappings of a traditionally masculine man. He’s flannel clad, baseball cap wearing, and has a beard that would make most men jealous. He’s in a traditionally masculine trade, carpentry and contracting. His masculinity cannot be put on trial because he is a masculine character, but he is a good example of non-toxic masculinity — and his non-toxic masculinity is put into sharp contrast with Howard’s overbearing and looming toxic masculinity.

Emmett isn’t afraid to sit around and read the girls’ magazines that were supposedly Megan’s or take the quizzes in them. He even offers to braid Michelle’s hair because he read an article on it. From the time Michelle meets Emmett, he goes out of her way to make her feel comfortable. During the nerve wracking and awkward dinner scene, he makes jokes at his own expense to put Michelle at ease and try to defuse the situation as a whole.

By his own admission, Emmett’s not a book smart individual, but it becomes clear that he is definitely an emotionally intelligent person. He allows himself to be emotionally open with Michelle and initiates a discussion in which he reveals he ran track in high school and was good enough to get a scholarship to attend college. Emmett, not thinking himself smart enough to make it in higher education, sabotaged himself by getting drunk the night before and missing the bus that would have carried him off to a whole new life.

Michelle reveals that she, too, has similar regrets involving what she herself didn’t do. She, in turn, tells him her own personal story about how she was shielded from her abusive father by her elder brother. When she was faced with the chance to be a protector of a girl who was being manhandled by her father in a hardware store, but she froze up and was unable to act.

Emmett and Michelle share a special connection, and not long after their emotional exchange, they bond and become good friends. The turning point in the movie is when a problem with the bunker’s air filtration system arises. Michelle has to crawl through the vents, seeing that she is the only person small enough to do so, to get to the system and repair it. There she finds the word help scratched into the glass of a hatch type door and an earring with blood on it. Michelle tells Emmett about these findings and how she fears he held Megan captive and then killed her.

Michelle shows Emmett the picture of Howard and “Megan” that Howard had shown her earlier, and Emmett confirms that the girl in the picture is not of Howard and Megan but of Howard and a girl from the community who went missing a couple of years prior. All of their uneasy feelings toward Howard have been confirmed as something beyond suspicion and made concrete. At this point, they’re forced to take action. Michelle devises that they build a hazmat suit and a gas mask from items that are found around the bunker.

How both men regard Michelle is important to take note of.

Emmett respects Michelle and her agency. He doesn’t act entitled to her attention or her as a human being like Howard does. Emmett sees Michelle as she truly is: a competent and fierce woman. How Emmett views Michelle is set in stark contrast to how Howard views her. Howard constantly infantilizes Michelle and refuses to see her as anything but young girl.

Toward the start of 10 Cloverfield Lane, when Michelle ventures out into the bunker, her knee is injured and her movement is aided by a crutch. Understandably, Michelle falters and nearly falls in her unsteady state. Emmett reaches out to steady her and instantly meets Howard’s rage. He doesn’t want Emmett touching Michelle. He acts like an overly possessive father or boyfriend who doesn’t want their child or significant other being touched by another person, despite the touch being extremely innocent in nature.

He enforces a rule that the two are not to touch, as if Michelle cannot make the decisions for herself involving who she wants touching her and having access to her body. Howard seeks to strip her over a sense of autonomy. While playing a game, Emmett is trying to describe the title of the book Little Women. Emmett, of course, uses Michelle as an easy example for the word woman. Howard, not seeing Michelle as a woman, causes Michelle and Emmett immense discomfort and his guesses include ‘little girl’ and ‘little princess.’

Eventually, a jealous Howard finally finds an excuse to extract Emmett from the situation as Emmett’s presence is not ideal, and Howard sees him as competition for Michelle’s attention and affections. Michelle is caught in middle between toxic and nontoxic masculinity, and the results are disastrous.

Those who exhibit toxic masculinity, and those who fall prey to it, often villainize men who display masculinity in a nontoxic way. Men with nontoxic masculine traits are viewed unfavorably, and toxic masculinity implies that nontoxic men are somehow lesser.

Howard discovers a pair of scissors and a box cutter that Michelle and Emmett were using to create the hazmat suit and gas mask. He confronts them about it, and in the midst of the confrontation, Emmett takes the blame for it, stating that he was going to use them as a weapon to procure Howard’s gun as a way to impress Michelle.

Emmett’s flimsy faux confession is all Howard needs as feasible permission to eliminate an unwanted variable from his equation. Howard forgives Emmett, and Michelle breathes a small sigh of relief, but that sigh of relief soon turns into screams of stunned terror when Howard shoots Emmett merely seconds after supposedly forgiving him.

Howard thinks little of how Emmett’s grisly murder will effect Michelle’s psyche. Emmett represented the sane outside world for Michelle, a world that Howard doesn’t tarry in. Emmett acted as a sort of buffer from the sinister presence of Howard with his goofy and gentle companionship. After Emmett’s death, there is a significant tonal shift.

Michelle is truly alone now with Howard, a situation which instills a heady creeping dread in the watcher. There is a sense of urgency, and Michelle realizes that now is the time to enact her plan and leave before the situation becomes worse.

10 Cloverfield Lane presents Michelle’s feminine skill set and resourcefulness as an asset instead of a drawback.

We learn early on that Michelle wanted to design clothes and has experience with making them. Even in the start of the film, she has dress forms in her flat and makes sure to grab her beloved sketch book filled with her designs to take with her as she hits the road. Textile design and the making of clothes in general has long been associated with women and that type of work has historically fallen to them. Michelle uses her knowledge of textile design and production to make a hazmat suit from a plastic shower curtain and duct tape.

In addition to traditionally feminine arts being depicted in a useful and ultimately lifesaving way, Michelle’s femininity as a whole is never shown to be a drawback or a weak point in her character’s make up.

Many writers and filmmakers fall prey to the idea that masculinity is equal to strength and femininity is equal to weakness, coding traits in a long enforced and demeaning gender binary that they use to determine the mettle of a character. Traditionally feminine coded — despite whether that character identifies as male, female, or gender nonconforming — characters have often been depicted as weaker and more delicate than their more masculine counterparts. Michelle’s strength and femininity are allowed to co-exist and not come into conflict with one another because the filmmakers of ’10 Cloverfield Lane’ realize that strength does not correlate to one particular side of an outdated gender binary.

In turn, Michelle is also not given the treatment of being an idealized version of a woman. Michelle is allowed to have flaws instead of being upheld as some paragon of perfection.

In fact, when the audience meets her, she’s in the middle of a panic, and she’s leaving her boyfriend over a situation that is implied to be fixable. Michelle even admits that she runs away from situations when they get bad, no matter what they are or how simple they might be. She’s filled with regrets about the things that she hasn’t been able to do. During the emotionally charged confessional scene between her and Emmett, it’s difficult not to identify with Michelle. She’s human just like the viewer. We’ve all reacted badly to situations, we’ve all regretted something, we’ve all been in a situation where we should have done something but we didn’t.

What is even more important is that the narrative doesn’t judge her for her shortcomings. Her story arc comes full circle when, at the end, she is given the moral decision after hearing on the radio that help is needed to fight the alien invasion.

Michelle is no sacrificial lamb in ‘10 Cloverfield Lane’. She’s not a mere prop or martyr to be used to further the plot of the film. The film simply cannot function without Michelle and her dynamic characterization that is bolstered by Mary Elizabeth Winstead’s subtly haunting performance. The film is firmly grounded by her and her experiences. Michelle is a tacit survivor from the very start, so much so that even in the most tension-filled moments we have a sense of unwavering confidence in her and believe that she will be victorious. In a completely unpredictable movie, the audience has a safe bet in a miraculously wrought heroine.

10 Cloverfield Lane could have gone terribly wrong on many different levels. The film in and of itself is a high concept feat, a blending of several different sub genres that fall under the larger umbrella of horror.

The creative team pulled together a taut movie that acts as compelling drama, a nerve-wracking thriller, a science fiction/horror love child, and when one pulls back the layers, a sharp social commentary that makes pertinent points about toxic masculinity and the frightening world all women have to live in.

It’s impossible for this viewer and writer to ignore the socially thematic elements in 10 Cloverfield Lane because of how I have to constantly keep my guard up as a woman in this world. We’ve all been Michelle at some point in time, having to tiptoe in a hellish landscape of toxic masculinity that seeks to crush us, possess us, and even kill us.

1 Comment

1 Record

JARED MONTAUG wrote: