Controversial, disturbing, thought-provoking, and at times hilarious, “Poundcake” delivers equal parts horror, satire, and social commentary.

Have you ever watched a film that took you on such a chaotic, disorienting ride that, once the ride ended, you weren’t sure if it was exhilarating, horrifying, or nauseating? With your head spinning, you try to make heads or tails of what you just experienced. And there are no words to articulate what you’ve seen or the places you’ve been.

That was my experience watching Poundcake, which is unfortunate when you’re a film critic whose job is to critique and comment on cinema.

The films that excite me the most often come with a big fat warning label: not for everyone. The more subversive, provoking, and off-the-beaten path a film is, the more I tend to appreciate and admire it.

But Poundcake is an odd duck, indeed.

It’s a film that doesn’t just happen to polarize audiences. This isn’t The Witch, artfully reinventing the genre and dividing audiences between those who embrace elevated arthouse fare and those who prefer the more traditional trappings of the genre.

No, no. Make no mistake: Poundcake doesn’t accidentally divide audiences. It does it intentionally, with a bombastic ferocity that is either impressively bold or completely unhinged.

Like all the best things in life, it’s likely a little of column A and a little of column B.

The latest from prolific actor and filmmaker Onur Tukel, Poundcake is a controversial film by a controversial artist.

It wants to push your buttons, challenge you — even offend you. Ultimately, however, Tukel describes the movie as hopeful.

Is it possible we can appeal to our better angels, get over all our petty and divisive bullshit, and come out on the other side better, even if we are more than a little battered? Maybe.

But before reaching enlightenment, we must wade through a slog of sewage and endure the onslaught of human excrement.

As I watched, I asked myself, “Is this just a film about how people are the absolute worst and utterly irredeemable?” The answer: kind of. But, in fairness, it’s about more than that. At its core, it’s a political satire about the state of America, which is really its own kind of horror show.

It asks how we tackle the dangerous rhetoric and ideology without swinging the pendulum too far to the equally dangerous world of censorship, free speech infringement, and thought policing. How do we combat hate without simply redirecting it into another form of hate? What does genuine inclusivity mean, and is it possible in a world with such a deeply ingrained “us vs. them” mentality?

There are no sacred cows in this film.

No one is safe from ridicule. Neither the right nor left avoids skewering, and Tukel comes just as hard for lefty activists and hypocritical, performative do-gooders as he does for right-winged bigots.

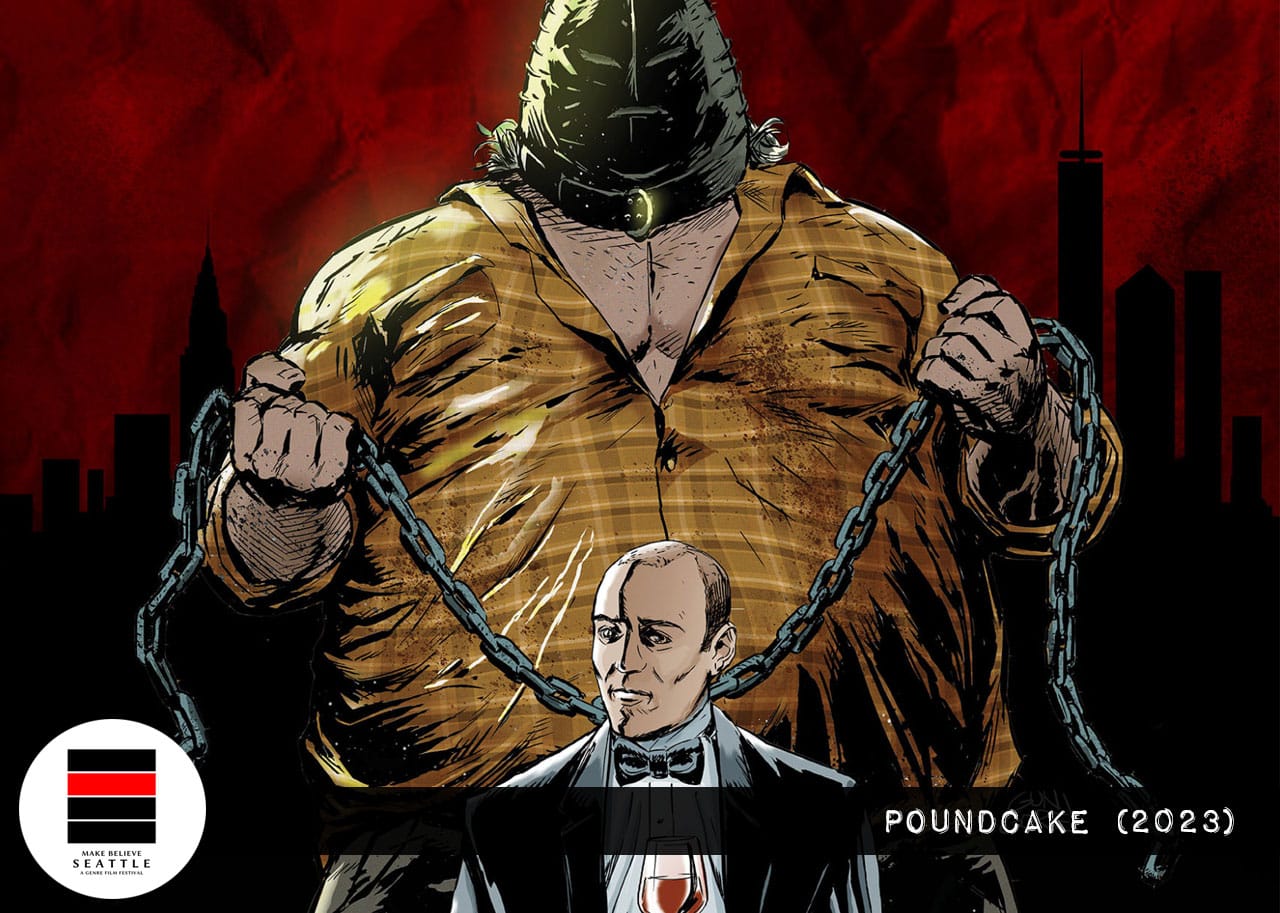

Poundcake is inspired by 80s slashers, and Tukel clearly has a fondness for the genre.

Visually, his masked murderer is imposing; a hulking man in a gimp mask and flannel shirt, wielding a chain that he uses to strangle his victims. In another film, this setup could be legitimately terrifying. In this film, the emphasis is far more on satire than slasher.

The absurdist comedy and social commentary reign supreme here. There’s nothing scary about it unless you count the horror of human nature, which is admittedly nightmare-inducing.

The kills are intentionally devoid of tension and are, instead, meant to disturb and disgust you. In fact, they are often infused with humor to distract you from their barbaric nature. In this sadistic scenario, the killer’s weapon of choice is his penis. He is raping his victims to death.

Now, that sounds unspeakably horrific. And, of course, it is. But there’s a twist.

The killer only targets straight, cis, white men. And because it’s those at the top of the food chain who are being dealt this horrific hand, these murders are being met with indifference, mockery, and even glib satisfaction.

Most people simply don’t care, and many others go so far as to call the serial killer a champion of justice, a scrappy anti-hero worth cheering on.

In a clever narrative twist, Tukel uses numerous vignettes of podcast discussions to frame the story while the murders happen in the background.

In one of the opening scenes, two Black women discuss the murders. One woman explains that White men are being hunted and brutally murdered. The other says, “That’s horrible,” and, without missing a beat, the other asks (quite sincerely), “Is it, though?”

She goes on to make an impassioned case for “justice” by pointing out that White men have been raping for centuries — not just women, but the land, the earth, and precious resources, too. Is it really so horrible if someone finally turns the tables on the oppressor?

As audience members, we’re lured into this type of thinking, forced to confront the reality that our own real-world reactions might not be far off from the onscreen portrayals. In fact, the opening scene gives us a bit of casual misogyny before the first victim meets his demise. If the White man is the devil, maybe this is just a good bit of karmic justice.

But not so fast.

Immediately after this healthy dose of potentially justified Black girl outrage, we meet two vapid, trust-fund baby White girls who are beyond insufferable. Later, they invite an Asian woman onto the show to bemoan how rich, White men are the source of all evil. The Asian woman calls them out. “Both of your fathers own hedge funds. You come from money. You don’t have jobs.”

And then we’re reminded of the many Karens of the world, the misandrists, and the “feminists” who actively exclude certain women from the conversation.

Then there’s the sobering fact that White women, in impressive numbers, supported Trump for president in 2016 and 2020.

Openly antagonistic to women and proudly sexist, Trump carried 47 to 52 percent of White women in suburbs while facing an opponent who was a WHITE WOMAN.

In 2016, Trump defied expectations to win the White House after allegations of sexual assault rocked the final weeks of his campaign. And in 2020, after four years of blatant bigotry and sexism, the female electorate remained largely unchained, with Biden barely eking out a win.

In polling, White women claimed to have second thoughts about the president, citing concerns about the mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic, his numerous public scandals, and his divisive racial rhetoric. They voted for him anyway.

In 2020, among White women, according to NBC News, 43 percent supported Biden, and 55 percent supported Trump. Meanwhile, 91 percent of Black women and 70 percent of Latina women supported Biden.

White men can be problematic as hell, no doubt. But as a White feminist woman, I’d have to be willfully ignorant to ignore how problematic White women have been.

But at least we can count on the non-Whites to save the day, right?

NOT. SO. FAST.

An Uber driver drops off his rich, White male passenger and beautiful Asian girlfriend (the same one we later see visiting multiple podcasts, including the aforementioned “two rich White girls” podcast). The driver, a Black man, starts yelling obscenities at his passenger. Dumfounded, the White man threatens to leave a negative review. “You can’t do that,” the Black man informs him. “White passengers are no longer allowed to leave negative reviews for Black drivers. Because… racism.”

Distraught and dismayed, the White man throws a tantrum in front of his Asian girlfriend. He tries to explain how he’s a good guy who deserves better, launching into the all-too-familiar “not all men” speech by emphasizing how much he cared about #MeToo.

“I stopped watching Louis C.K. for that. That was hard on me.”

When he explains how his driver hurt his feelings, his girlfriend tells him not to worry because the driver was garbage. She repeatedly emphasizes his Blackness. Uncomfortable with how the rhetoric has turned, the man informs his girlfriend she can’t talk that way. And it’s revealed she hates Black people. Uh-oh.

After she leaves, the man calls his mom and blames her for not being harder on him, making him too soft and hurting him because now he’s too sensitive. It’s always a woman’s fault. Then the killer arrives out of nowhere, shows up in his apartment somehow, and murders him.

Again, it’s hard to feel too bad.

Later, the Asian woman appears on the podcast of two Black men. They invite her on to celebrate her for her vicious takedown of two White women. Surely, she’s an ally. Wrong.

She calls them out for the terrible behavior of Black men. “You’ve been spreading hate, too,” she chastises them. The Black community, she argues, is misogynistic, homophobic, and racist against Asians and Hispanics. They “counter” by referring to women as bitches and then telling an Asian woman to “Chill out, Mulan.”

In addition to the podcast segments — which also include a group of pot-smoking comedians who debate if there’s such a thing as a line you shouldn’t cross when it comes to making jokes and free speech — we get a couple of sides stories involving an office from hell and a fight for a coveted promotion, a man trying to accept his Black gay son, and a couple grappling with the man’s sexual proclivities (played by Tukel himself).

The film packs so much commentary into its runtime that I would have to write a thesis to cover it all.

Topics range from conspiracy theorists, corporate politics, discrimination, sexual harassment, a uniquely female perspective on the #MeToo movement, male fragility, the canceling of comedians, “nice” guys who turn into monsters the moment they are rejected, the pressure to choose a tribe, hypocrisy, fake activism, entitlement, generational divides, and the ridiculous idea that a song can save the world. (Can you “Imagine”?)

The ending is ridiculous, over-the-top, hilarious, and even surprisingly poignant. We discover that the killer is really a manifestation of hate. He shows up when there’s too much noise and static.

Tukel, a controversial figure in film circles who has been kicked off podcasts (“Doug Loves Movies”) and done battle with film festivals, regularly seeks out challenging subject matter. He’s an impassioned advocate for free speech and expresses contempt for things like “safe spaces” and “trigger warnings” championed by some on the left.

He’s forthright about the issues he wanted to tackle with Poundcake.

“The culture has been hijacked by a small group of entitled, whiny brats on both sides. You’re either a racist or a rapist or a misogynist or a homophobe or a transphobe or an ableist or a baby killer or a rich prick or a freeloader or a right-wing Trumpster or a left-wing socialist or a milquetoast libertarian.”

He goes on to add:

“Most people are sick of the perpetual finger-pointing and name-calling. It’s like we’re in middle school. POUNDCAKE is my attempt to mollify the discord a bit. Sometimes the best way to criticize a specific moment in time is to mock it.”

Your mileage is definitely going to vary with this one.

Ultimately, it’s about how we judge a group of people for the bad actions of a few. And that goes for everyone in Tukel’s mind: the police, Catholic priests, Muslims, and especially cis-gendered White men. Most people are good, but we’re all guilty of judging others and “othering” people who don’t see the world as we see it.

Tukel uses a talented, diverse cast to help drive the conversation, representing many unique points of view and dubious thinking on every side.

However, many will find it problematic how it levels the playing field so wholly that no sin or sinner is more vilified than any other. That means ignorance and bigotry in the Black, Asian, gay, and feminist communities are just as criticized as things like homophobia, misogyny, ageism, and racism.

For those of us with liberal leanings and members of these minority communities, that can be a bitter pill to swallow. But that’s the point of the film.

Tukel aims to spotlight hypocrisy in all its form and call out how complicit most of us are in creating and sustaining a society that emphasizes our differences and forces us to choose sides in an ongoing cultural war.

If you find sick satisfaction in watching “the enemy” get brutally raped and murdered, if you find it hilarious even, are you really as enlightened and accepting as you think you are?

Though it takes a divisive path to get there, the film ultimately seeks to unite and asks us to consider the ramifications of publicly preaching about love and acceptance and then being gleefully eager to let hate and anger divide us.

It’s not going to be everyone’s cup of tea, and the fact that it uses rape as a central plot device won’t sit well with many. But, as a film meant to be a conversation starter, it does its job. There are some thought-provoking ideas here and no easy answers.

Is it a home run? No. But it’s provocative, challenging, risk-taking, and unafraid to ruffle feathers. For that, I sincerely applaud it.

Follow Us!