Mike Flanagan’s films are more than great genre entertainment; they are meaningful explorations into the lasting, terrifying effects of childhood trauma.

The filmography of horror maestro Mike Flanagan isn’t easy to denominate, but if I had to, I’d place it into the Honey, We’ve Traumatized the Kids sub-genre.

Aside from his feature film debut, Absentia, the Flanaverse is bursting at the seams with childhood trauma and explorations of how that trauma manifests into adulthood. From the world of Oculus, which tells the tale of a brother and sister at odds about the reality of a supernatural mirror disintegrating their family and destroying their childhood, to his most recent Stephen King adaptation, Doctor Sleep, Flanagan has a made a career out of making space for deeply broken, fundamentally flawed, and tragically traumatized children.

Perhaps the most powerful examples of this can be found in his Netflix original, The Haunting of Hill House, and the dark fantasy darling Before I Wake.

The Haunting of Hill House is a contemporary take on the esteemed Shirley Jackson novel of the same name that explores the lives of the five Crain children and the fateful night that would follow them for the rest of their lives.

On a stormy night in 1992, the Crain children are herded into a car by their father and driven away from home, where their mentally-ill mother Olivia, lay dead on the bottom of the stairs. In the present day, it is clear that the Crain siblings have all but moved on from the events that transpired at Hill House.

Stephen is cynical and ill-regarded within the family for capitalizing on their childhood trauma with an embellished memoir on their former haunted home. Shirley is a control-freak with marital problems stuffed deep into an emotional pressure cooker. Theo is a heavily-guarded ball of rage with a drinking problem. Luke is addicted to drugs, and Nellie is…dead.

While it’s been confirmed that the Crain children are representative of Elizabeth Kubler Ross’ 5 Stages of Grief, they are so much more than that.

The lives of the Crain children, particularly Nellie, are tributaries of trauma flowing separately towards the same convergence – the mouth of Hill House.

Nellie Crain, the final victim of Hill House, spent her entire life waiting to be seen, to be heard.

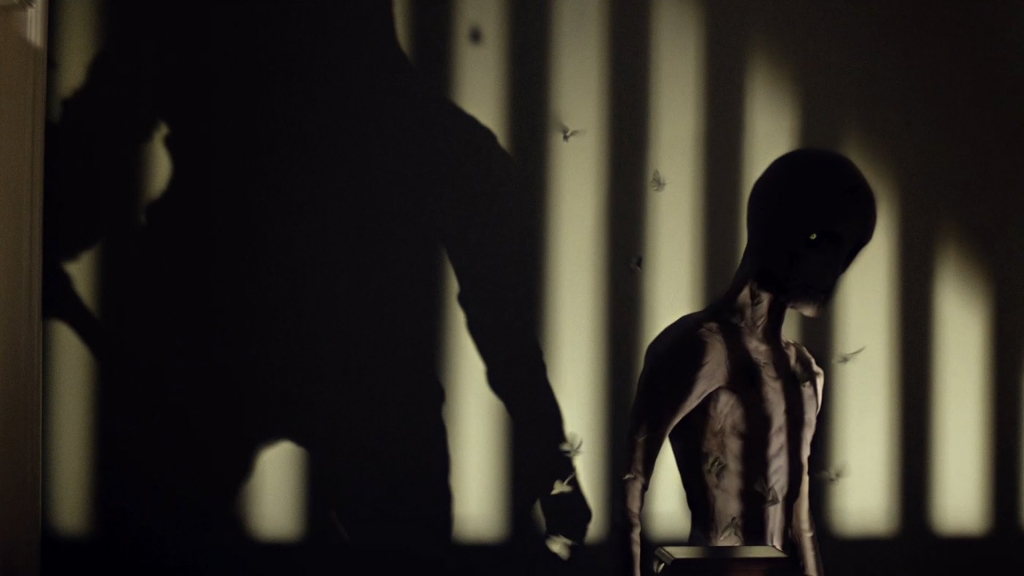

After moving into Hill House with her family, Nellie found herself plagued by sleep paralysis and visions of a female specter visiting her in the depths of the night. The woman, whom she named The Bent-Neck Lady, followed her into adulthood.

As a little girl, Nellie tried her best to ask for help. She told her parents about The Bent-Neck Lady, but they disregarded her descriptions as the consequences of an active imagination. Her siblings, especially her twin Luke, claimed they believed her – but only as far as other children can believe the dreams of their peers. Into adulthood, Nellie found herself in a position similar to many other leading women in horror…on the verge of an emotional breakdown.

Having inherited her mother’s mental illness, adult Nellie rarely received validation from her siblings.

Any cries for help were dismissed as overreaction or worse, an episode. When Nellie decided to confront Steve about his exploitive writings – he banished her from the site after demeaning her mental health. And as The Bent-Neck Lady continued to haunt Nellie’s dreams, no therapist, no doctor, no sibling believed her…until she met Arthur.

When Nellie meets Arthur at an appointment for a sleep study on how to manage sleep paralysis, her relief is palpable. At last, somebody is not only willing to listen to her…but he believes her.

They fall in love. She tells him the stories of The Bent-Neck Lady. He stays, he listens, Bent-Neck Lady retreats until the night he dies. Nellie is back to having no one by her side. Her therapist refuses to acknowledge the power of Hill House, and her siblings all decline her calls for help.

Nellie spent her life screaming for help, and nobody listened.

Trauma in the works of Mike Flanagan so often operates with an insidious undercurrent.

The trauma is painful and dangerous, but it rarely costs the victim their lives. Instead, it is the forced silence that kills them. It is the disbelief of others that pushes them off the ledge. It is the suppression of truth that pulls the trigger.

Nellie spent her life fighting for validation and found herself screaming into a vacuum of generational trauma. No matter how loud she was, nobody could hear her. The moment she succumbed to the silence and met The Bent-Neck Lady at Hill House, becoming her, was the first time the Crain family could hear, feel, or see their sister.

Like the ghosts hidden in the corners and crevices of Hill House, Nellie’s trauma could only be seen when the Crain family knew to look for it. This is what makes young Nellie’s line in episode 1.06 so entirely heartbreaking.

“I was right here. I didn’t go anywhere. I was right here. I was right here the whole time. None of you could see me. Nobody could see me.”

The tragedy of Eleanor Crain is that she did everything she could to save herself, but the disbelief and disintegration of her support system failed to deliver her a living salvation.

Before I Wake explores the aftermath of trauma much differently than The Haunting of Hill House, with equally devastating consequences.

After the accidental drowning of their young son, Jessie and Mark Hobson take in Cody, a foster-child suffering from a hellacious dreamscape ruled by The Canker Man. Much like Nellie, Cody’s nightmares are written off as harmless. As Cody adjusts to life in his new home, he struggles to sleep at night, and to stay awake during the day.

Little by little, strange incidences begin to occur around fits of sleep for Cody.

A boy at school with whom Cody doesn’t get along with disappears. Luminescent butterflies appear in the Hobson’s living room. One night, after seeing a picture of the Hobsons’ late son, Cody dreams of him. Jessie and Mark see their dead son and embrace him, but his likeness dissipates when Cody awakens.

Despite being aware of The Canker Man, Jessie decides to use Cody’s gift of somnilomancy to conjure up constant visions of her dead son.

In a desperate attempt to maintain the illusion, Jessie gets a prescription for sleeping pills and drugs Cody, unbeknownst to Mark. Cody’s pleasant dreams quickly take a nightmarish turn and The Canker Man appears, devouring Mark in the process of wreaking havoc on Cody’s psyche. Jessie is thrown across the room and awakens shortly after, finding Cody on the phone with 9-1-1. Social services, suspecting that Cody has been placed in a violent home, relocates him for the night.

While the root of Cody’s trauma doesn’t become apparent until later in the film – the Hobsons’ dismissal of The Canker Man, and later Jessie’s exploitation of Cody’s ability, pose an immediate threat to those around the young boy.

Whereas Nellie’s trauma swallowed her from the inside out, Cody’s subconscious creations swallowed the waking world around him.

Jessie soon realizes her error and embarks on a journey to save Cody, whose dreamscape has once again passed through the subconscious divide as The Canker Man ravages the orphanage. Jessie faces The Canker Man and presents him with a token from earlier childhood. Before her eyes, The Canker Man shrinks and morphs into Cody himself.

It is later revealed that The Canker Man is a product of Cody’s imagination. Cody’s birth mother died when he was just 3 years old of pancreatic cancer. The Canker Man was given power by the trauma of Cody witnessing his mother wilt away during chemotherapy, and the misinterpretation of the word “cancer”.

The Canker Man, like The Bent Neck Lady, is the monster that trauma becomes when it’s not acknowledged.

Though these two works are observations on the effects that trauma has on the body and spirit, they both have hopeful conclusions.

Nellie and her family are afforded the opportunity to communicate at Hill House, to truly witness each other’s last pain and resolve to move forward together in the power of recognition.

Jessie and Cody discuss the life and death of his birth mother, distilling that trauma until it becomes a grounded reality rather than a monstrous nightmare.

These endings are earned. They are a glimpse into what can happen when we are willing to listen to the trauma of others, and to our own.

Flanagan has an unmatched ability to tell stories about children as they are traumatized, and who they will – or can become as a result. By telling these stories and contextualizing the ramifications of these horrors, Flanagan teaches his characters and audiences how to reconcile with their own trauma, and how to tend to the wounds of the child that remains in all of us.

After all, don’t we just want to be loved, to be seen, to be heard?

Follow Us!