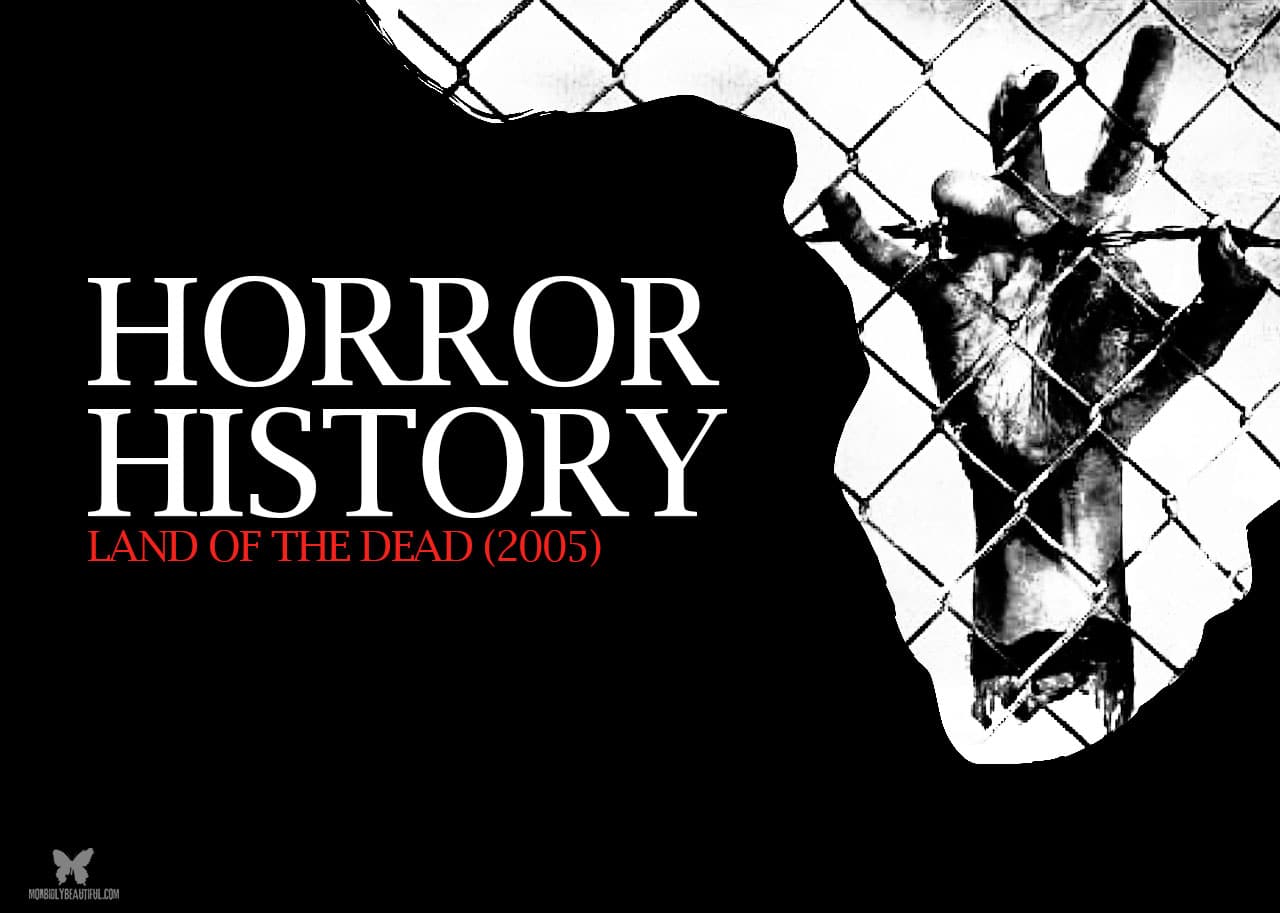

Failing to receive the lasting recognition it so deserves, Romero’s “Land of the Dead” has only gotten better and more relevant with time.

On September 11th, 2001, the world changed forever.

The great untouchable giant that was the United States of America awoke that luminous morning to find itself under attack by an assailant that launched a suicide bombing mission designed not only to kill thousands but simultaneously initiate an epidemic of fear that would shake the foundations of the free world. And they did it all with four airplanes and their flesh-and-blood bodies, hurtling roaring steel and swishing gasoline into the Twin Towers, the Pentagon, and the hills of Pennsylvania.

That day, chaos reigned supreme. It was everywhere, spreading like a sickness as two skyscrapers plunged from that great blue sky, a toxic storm cloud following the twisted metal that crinkled like a fist around our nation’s heart.

People all over the world watched in horror as it was introduced to a new kind of enemy, one that could be lurking inconspicuously in any given place at any given time. A terrifying concept, especially when the dawning realization hit that these terrorists were willing to sacrifice themselves in order to carry out their mission, with more waiting to fill those vacant ranks.

Of course, America declared that the attackers would be brought to justice and terror would be eradicated from the world with a vaccine of bombs and bullets.

President George W. Bush rallied a nation that was angry, confused, and dazed by the black eye dished out by an enemy we were just barely starting to understand. Looking back, that initial swell of patriotism that coupled with the thirst for retribution was something I think most folks felt. There was no greater pride in the country, and any regime foolish enough to tangle with the mighty force of the United States would face a decimating reckoning.

Little did the citizens of the United States – and the world, for that matter – know what would follow.

An unending war would commence, spreading from Afghanistan into Iraq, where supposed “weapons of mass destruction” lurked in the parched deserts under the iron fist of Saddam Hussein. Even worse, more terror attacks occurred around the globe. President Bush insisted we were on the path to victory, even as doubt began to form over the scabs left from 9/11.

The United States found itself on a suicide mission, assuring its citizens – and the world – that everything was under control. That we would win this fight.

In the wake of the attacks of 9/11, the horror genre found one of its sleeping giant subgenres prodded back to life.

Much like the shambling cannibalistic corpses at the heart of the genre, the zombie film staggered out of the grave eager to take a chomp out of our new-found fears.

The first out of the graveyard was British director Danny Boyle, who effectively reconstructed what it was like waking up to a catastrophe with 2002’s lo-fi 28 Days Later.

It was just the shot in the arm zombies needed to come roaring back at our jugulars. However, I recognize and understand that the debate rages over the rampaging maniacs at the heart of Boyle’s classic are actually “infected.”

In America, screenwriter James Gunn and director Zack Snyder followed Boyle’s lead with the 2004 remake of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead. Vigorous, colorful, and offering a refreshed interpretation (and one hell of an opening, might I add) of Romero’s 1978 masterpiece, Gunn and Snyder further aroused the hunger for more of the undead.

The same year Dawn of the Dead 2004 attacked our institutions and reflected upon that fateful Tuesday, director Edgar Wright punched up both zombie and Romero fever with Shaun of the Dead, an adoring valentine (and subtle 9/11 deconstruction) to the master.

As zombie mania was reaching a fever pitch, Romero’s own body of work was enjoying a renaissance of sorts on physical media.

Dawn of the Dead 1978 had just seen a fancy DVD release from Anchor Bay, followed closely by 1985’s Day of the Dead (with wicked cool packaging on both, might I add). The extras on the DVDs found Romero dropping the bomb that he had an idea for a fourth installment in his Dead trilogy that kicked off in 1968 with Night of the Living Dead.

With zombies finding their wobbly footing, it would make sense for another sleeping giant to awaken.

Enter 2005, when the summer movie season found itself jam-packed with blockbuster after blockbuster. George Lucas ended his soulless Star Wars prequel run with Revenge of the Sith, Steven Spielberg rattled us with a brittle War of the Worlds remake, the Caped Crusader launched his own war on terror with Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, and Tim Burton used Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory to suggest karma could be a real bitch with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Also present were 40-Year-Old Virgins and some Wedding Crashers to give America something to giggle about.

Smack dab in the center of all these big-studio event movies was the famously independent George A. Romero, the legendary horror giant finally getting his due with the epic, Universal Studios-backed Land of the Dead — a return fit for a king.

Land of the Dead picks up well into the zombie apocalypse, with the city of Pittsburg (the place Romero called home and filmed around for many years) now a walled-off fortress from the roaming undead. In the center of the city sits Fiddler’s Green, a twinkling skyscraper reserved strictly for the elite.

Fiddler’s Green is overseen by Kaufmann (played by Dennis Hopper), a wealthy, cigar-chomping businessman who has carved out a place where the privileged can live like the world never stopped turning. At his command is an army of trigger-happy mercenaries led by Riley Denbo (played by Simon Baker) and Cholo DeMora (played by John Leguizamo), who descend upon the surrounding areas to pillage for supplies with the help of their super-weapon, “Dead Reckoning,” a heavily-fortified war machine outfitted with an array of hefty artillery.

Meanwhile, the undead have begun showing increased signs of intelligence, with many of them trying to mimic their former lives.

After one particular zombie, Big Daddy (played by Eugene Clark), takes notice of the savagery the mercenaries use while combing for supplies – and spoils for the residents of Fiddler’s Green – he begins to rally his fellow ghouls to follow Kaufmann’s troops back to Pittsburgh and launch a devastating assault on the city.

As the zombie army makes its way toward the Steel City, Riley and Cholo both announce they plan on retiring from working for Kaufmann.

Riley, who is the creator of “Dead Reckoning,” plans to slip quietly away to Canada with his sharpshooter sidekick, Charlie (played by Robert Joy), while Cholo believes that he can buy his way into Fiddler’s Green, which Kaufmann is quick to turn down. Enraged with Kaufmann’s rejection, Cholo steals “Dead Reckoning” and holds the city for ransom. With very few options, Kaufmann turns to Riley and Charlie, who, along a resourceful prostitute, Slack (played by Asia Argento), and a team of commandos, set out to track down Cholo before he can shell the city.

Upon its release, Land of the Dead was warmly welcomed by most critics and die-hard horror fans with open arms.

It was a thrill to see Romero finally working with the tools to be able to craft the ultimate zombie masterpiece. Hell, that is what the posters and advertising promised! Who couldn’t be excited about it?

During its theatrical run, Land of the Dead, which was made on a budget of around $19 million, gobbled up over $40 million, which certainly isn’t a number to shrug a diseased shoulder at. For a theatrical release, Land was insanely violent; the level of carnage in a mainstream release like that truly shocked me when I first saw it on opening night (I can still remember the chums I saw it with!).

And let me tell ya, I was beaming from ear-to-ear that good old George hadn’t softened since Day of the Dead took theaters in ’85.

It was an honest-to-goodness slaughterhouse that never once sacrificed any of the shrewd wit Romero had made a name with.

With the reaction largely positive to Land and interest in zombies still high, Romero was able to helm two more zombie films, 2008’s Diary of the Dead and 2010’s Survival of the Dead, the latter being the horror legend’s final cinematic venture.

He also whipped up Empire of the Dead, a cool little Marvel comic book that expanded the scope of his Dead series even further with the incorporation of vampires, which was most likely a nod to his beloved 1977 thriller Martin.

He also had begun chipping away at a sprawling novel, The Living Dead, a towering epic that explored the zombie apocalypse from the very beginning. Of course, The Living Dead wouldn’t hit bookstore shelves until after his death in 2017, but it was a wonderful final gift to his fans that played like a summer blockbuster in the palm of your hands.

Eighteen years on, looking back on Land of the Dead is sort of peculiar.

It arrived just as zombies were at their most popular; a good chunk of his fans enjoyed it, critics gushed, and fellow horror directors sang its praise. And then, it sort of shambled into the background of the zombie hoard.

It was a welcome expansion after Day of the Dead, even if it felt like some of the blue-collar ingenuity was replaced with Hollywood panache. There was a big budget gloss brushed onto Land, something that his fiercely independent previous offerings were without. Obviously, that isn’t a dig at the Night, Dawn, or Day, all of which were constructed with the help of friends who filled roles both in front and behind the camera.

They were stunning testaments to what could be achieved when you rallied a group of crafty regional artists together in the sacred name of art. They bucked the system, and they were all the better for it!

From an aesthetic standpoint, Land overwhelmingly felt like a studio film to the point where you can almost feel the suits breathing down Romero’s ponytail.

And while there is electric fence-to-electric fence pizzazz crammed into its nimble hour-and-forty-minute runtime, Land wasn’t bashful to wear its message on its tattered sleeves.

In fact, Land felt the most overt of Romero’s zombie movies up to that point.

That is saying something considering it was always a bit obvious the lanky director had more on his noggin when he first unleashed the dead in ‘68.

In earnest, Romero maintained Night didn’t set out to be as politically charged as it turned out, but he was also no dummy. He openly admitted he was disgusted that the ‘60s didn’t turn out the way he had hoped, and you can feel his dwindling optimism as the zombie numbers rapidly rise in the dark.

If Romero is to be taken at his word, then he has no excuse for Dawn, which is a bit more palpable in its deconstruction of consumerism and greed.

Dawn also found a now-established filmmaker working with a bigger talent (Dario Argento), a smidge more money, and a bigger location that offered spiffier production value in contrast to the farmhouse he and his merry band of would-be movie-makers doused in chocolate syrup standing in for fake blood.

And then came Day, which was distinctive because it was said that Land was composed of material he couldn’t pull off with the budget he was awarded at the time of production.

A trimmed-down script, a chip on his shoulder over not being able to bring his ultimate vision to life, and a general disdain for humanity’s unwillingness to find common ground would usher in his bleakest and most multifarious zombie vision yet.

It was his least successful zombie picture at the time, and it’s easy to see why, as the characters consistently scream each other into rocky oblivion.

But make no mistake, Day is still a prime example of Romero rolling up his sleeves and reaching deep into the darkest depths of America’s soul.

Twenty years on is our focus, Land of the Dead, the most blatant zombie reaction to a post 9/11 world and how the Bush administration handled the aftermath.

It’s even less subtle than the Regan-era Day, which shrieked in agony while waxing philosophically about how we deal with a crisis. It opens with a raiding party using “shock and awe” tactics to distract the zombie populace at large, who could easily be stand-ins for the American public attempting to carry on with a sliver of normalcy in a world where that word had lost its meaning.

Or perhaps they could be the poor victims of Bush’s War on Terror, which evolved from a force looking to erase evil into an unruly and grotesque swipe for resources (cigars and high-end liquor stand-in for oil in Land).

Meanwhile, the clueless leader picks his nose and enjoys the excesses of his position, looking down on the sullen masses veiled by cigar smoke and a designer suit, where the divide between the haves and the have-nots was growing deeper and deeper with each paper cut from the stacking piles of dollar bills accumulating in his vault.

And then there is Fiddler’s Green and “Dead Reckoning,” the walled-off paradise where the wealthy can ignore the collapsed civilization across the river with the reassurance that they possess weapons capable of erasing an entire populace off the map.

Kaufmann feels invincible, much like America felt in the days leading up to 9/11. How naïve we were that a unified resentment was organizing and charging forth, our bullets cutting them down, with another body to push on its place with one sole objective – destroy the system and ignite terror. This is ultimately what would make zombies the boogeymen of a post-9/11 world.

It would also find Romero bluntly asking, what good are modern weapons like “Dead Reckoning” when the enemy isn’t afraid of them?

In the years since its initial release, Land of the Dead has aged like fine wine.

Much like Romero’s other Dead pictures, they continue to apply to modern-day U.S.A.

In 2016, infamously boisterous businessman Donald Trump was elected president in perhaps one of the most shocking and polarizing presidential elections in American history. From there, he launched a carnival-like campaign that began alienating America from the rest of the world. One of his campaign promises was that he would construct a wall around our southern border to keep out those he claimed were “bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists.”

And don’t forget that travel ban.

With America in turmoil from Trump’s steamrolling hate spreading among his cultish masses like a zombie epidemic, the character of Kaufmann takes on a whole new meaning.

It’s heavily implied that Kaufmann is corrupt, a money-hungry buffoon who loosely plays the leader but is more smitten with the unconstrained power it brings. He has zero interest in closing the divide that is right under his nose. He turns on those who work for him, refuses to listen to his cabinet, ignores anyone who opposes him, and when the zombie army initiates their siege on his (Trump?) tower at the end of the film, he growls, “YOU HAVE NO RIGHT!”

What’s even more curious are the characters caught between Big Daddy’s zombie uprising and Kaufmann’s ultra-exclusive castle on the hill.

Cholo, who has been forced to get his hands dirty for the man, is quickly denied access to a spot within the Green by an individual who will shoot one of his own cabinet members in the back to save his own bronzed skin. Meanwhile, Riley and Charlie are just looking for a peaceful existence, away from the division, squalor, and noise emitting from the monster in the golden crown.

But even they struggle to flee Kaufmann’s shadow as he finds a way to curb their search for solitude, his poisonous ego inching and nipping at their heels.

And we can’t forget to mention Big Daddy, the (literally) blue-collar zombie who saunters out of his mechanic shop only to see his quiet plot of suburban soil upended by a rioting band of “patriots” (one member of Kaufmann’s mercenary team uses a flag pole adorned with a blood-drenched American flag and a gleaming gold eagle on the end of it as a weapon) who are sparking the wick of mayhem all in the name of a self-absorbed leader who couldn’t give to flicks of his cigar (or sips of his Diet Coke) about them.

Perhaps the scariest aspect of Land of the Dead is the film’s final act.

A desperate Kaufmann and his chauffer try to sneak off in the midst of chaos as Fiddler’s Green falls to Big Daddy’s tuned-in legion.

With suitcases stuffed with cash, an angry Kaufmann unloads his pistol at the advancing cannibals, enraged that he is forced to give up his post as the leader. The ousted king is overcome with disdain that he’s lost his golden throne, sickened not at the damage that has been inflicted with his xenophobic rhetoric but that he can no longer pound his chest as leader of the free world, or at least those he believes can live free in his disillusioned, pearly-white fantasy metropolis.

And when Kaufmann meets his fiery demise, there was a ping of irony to him burning in a sea of gasoline and singed money, especially three years removed from 9/11 and Bush’s invasion of Iraq.

Now it’s evocative of Trump’s spiteful attitude towards the 2020 election – if he can’t rule the world, he will play the martyr and let it collapse in a heap of ashes. He’ll step on you as he rushes out the door, only to be met with a fireball of wrath from the ones he wronged in order to ascend into the heavens.

Earlier, I said that shortly after Land arrived, the film seemed to lose itself in a sea of countless other zombie efforts. Today, when we assess the zombie genre and some of its greatest entries, many are quick to put 28 Days Later, Dawn of the Dead 2004, and Shaun of the Dead before Romero’s triumphant return. When it comes up in conversation, Land is usually met with a shrug and a casual, “Oh yeah, that wasn’t bad” sort of response.

I can understand that the film may not scratch the itch quite like some other zombie movies of the time, which buried their message in swarms of sprinting ghouls or winking humor. Still, Land of the Dead is the work of a master who seemed like they were beyond trying to conceal the way they felt about the world around them.

That approach would continue with Diary and Survival, which are often considered the worst entries in Romero’s zombie series.

While Land of the Dead may not be perfect, it’s still a highly-octane and cerebrally compelling film that is unabashedly George.

It’s got the gore and an old-school action swagger. And it has those zombies who groan with the same charms they did in ’68, ’78, and ‘85. Still, Land of the Dead is bizarrely snubbed compared to other zombie efforts, specifically Romero’s original trilogy. No line of Fright-Rags shirts and no waves of action figures aside from a trio that arrived when the film first hit theaters. It has yet to achieve that nostalgic revival that other efforts of the time currently enjoy.

Dawn of the Dead 2004 just nabbed a 4K release and is streaming on Netflix, Shaun of the Dead got some spiffy t-shirt lines and a wonderful book that looked back on its production (You’ve Got Red on You), and rumors continue to swirl about a third entry in the beloved 28 Days Later franchise.

Strangely, Land of the Dead continues to wander about the zombie wasteland, with little attention paid to the film’s legacy.

If I had to guess why Land seems somewhat sequestered from the initial zombie renaissance, I would compare it to the way Kaufmann’s mercenaries use fireworks to distract the ghouls.

We, the American public, prefer fireworks, that radiant burst of tantalizing spark, over robust exercises that nudge us into confronting the ugliness occurring all around us.

And while extraordinary horror films like 28 Days Later, Dawn of the Dead 2004, and Shaun of the Dead certainly did churn with weightier themes, they did so behind a steady barrage of fireworks. In a show of defiance, Romero opts to ambush our expectations and shove our collective noses into our own stinking errors.

As the final page turns and “Dead Reckoning” cruises into the vast unknown, one can’t help but notice Romero identifying with our zombie hero, Big Daddy, that hulking fella who grew weary of the spectacle those “sky flowers” brought and opted to roar in the face of our homegrown aggressors.

Follow Us!