Mixing gothic horror and grotesque animated effects, “Viy” is a horror classic; an undeniably influential, dark Russian folktale about sin and retribution.

Viy may be the only horror movie that opens with an assurance that it is not based on a true story:

“Viy is a colossal creation of the imagination of simple folk. The tale itself is a purely popular legend and I tell it without change in all its simplicity, exactly as I heard it told to me.”

Though the “I” in this preamble goes unidentified, it belongs to Nikolay Gogol, who opened his short story with the same promise in 1835. 132 years later, when this second adaptation was produced as one of the earliest Soviet horror films, that promise was still bullshit.

Gogol cherry-picked broader European folklore — primarily Irish and Serbian myth — and invented his own Eastern equivalent. He included it matter-of-factly in a collection of less fanciful short stories about country-living in the Ukraine. The juxtaposition of Viy with a bitter fable like The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich, which hinges on a pig eating a contentious petition, only made the former more potent, the unbelievable sold by the mundane.

“Viy” isn’t even a word in Ukrainian.

In Gogol’s adopted Russian, “vyy” is the closest conjugate, meaning “out.” The equivalent Serbian monster, Vy, translates as “you.” Add the short story’s occasional alternate title, “The Viy,” to that pile and they’d all pass muster on posters hanging at your local AMC.

Blumhouse presents You. From the makers of It comes Out. A24 could sell artbooks for The Viy without even making the movie.

Pay no mind to the cheese-cloth cobwebs of the 1967 adaptation, either, because it’s similarly, surprisingly modern.

The byzantine spires of Russian Orthodoxy, bulging and profound with man’s phallic glory to Father God, give way to cackling seminarians making a goat read the Bible. The keepers of the divine flame are still learning not to play with it; the bishop reminds them not to get caught stealing chickens while dressed up like devils again.

The seminarians, especially the bowl-cut trio that the film follows, are genre-standard college students that just happen to wear crosses. Within seconds of being released for a break, they ransack the nearest village. Some steal loaves of bread, others live geese. The fairer sex is treated no differently than the livestock. Two men of the cloth catch a woman in her own laundry and haul her off, never to be seen again.

In the same way we’ve been conditioned to want the dumb jocks dead in any given slasher film, you can already see the gavel of supernatural justice rising for a verdict.

The seminarian on trial here is Khoma, a feckless dolt whose eyelids hang at perpetual half-mast. He takes the lead when his friends get lost after nightfall on the Russian moors. He’s the one that bullies a lonely crone for food and shelter she barely has. “Make an effort, just this once,” he urges, promising ill-defined reward come dawn.

Unlike his fellow philosophers, Khoma is sentenced to sleep in the old woman’s barn. She must’ve sensed something in him, because as soon as he shuts his eyes the crone comes knocking. Khoma assumes she wants him for his frock. After a quick game of Ring Around the Rosie, she curses his body in place, tilts it to the floor, and climbs onto his shoulders.

His cruel assumptions about her are accidentally, horribly correct; she’s a witch.

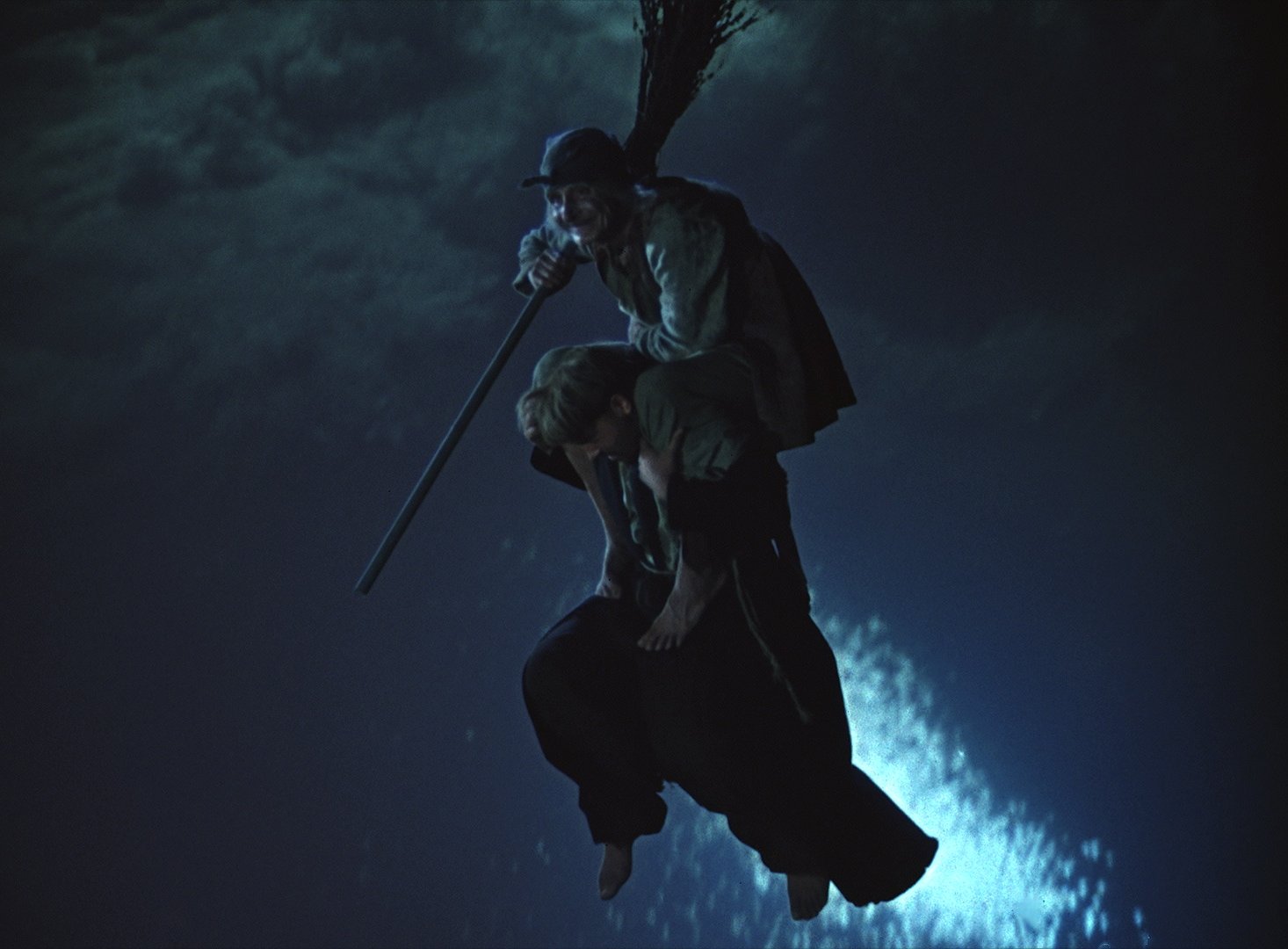

She leads him outside on piggyback, straight into Viy’s first special effect. The camera stays right beside them, and they stay right in the middle of the frame, but neither the camera nor the frame ever moves. Khoma and the witch are invisibly suspended over a grassy turntable. His bare feet only touch toes with the ground, the gap hidden by a squirming blanket of graveyard fog.

It’s a trick as old as film itself, all the seams plain as the artificial night, that has only gotten better with age.

What was dated even in its day – You Only Live Twice released the same year — is now dreamy, tickling the uncanny in ways rear-projection car chases only do on accident.

Then they start to fly.

“In the name of God, in the name of Christ, put me down!”

Khoma doesn’t try to reason with the unspeaking thing on his shoulders. He only shouts the magic words and puzzles out an ontological explanation. The witch can’t be flying of her own volition. It must be Jesus Christ and his apostle Thomas doing the heavy lifting.

Through no influence or fault of the almighty, the witch brings them in for a landing. Once Khoma collects himself, he beats her to death with a stick. Regret only touches his pious heart when she reverts to her true form: a raven-haired maiden fair.

Like anyone in a horror movie who has done something stupid and unspeakable, he runs. Khoma makes it back to the empty seminary just in time for his presence to be requested in the funeral of a young woman. When he reaches the village, half-drunk and half-dumb, Khoma discovers why she asked for him by name on her deathbed. It’s the witch, and she wants a rematch.

The second half of Viy is divided into three consecutive nights, as Khoma stays with the coffin in a cavernous chapel lit by candles that don’t stay that way and wallpapered with dead-eyed icons of saints that can’t help him. Every morning he tries to run. Every night he tries to survive.

Viy is so short — barely 75 minutes — that revealing the finer points of Khoma’s impromptu exorcism isn’t worth the words to do it.

Go in blind.

If you’re not already sold, consider the third act vintage Hammer horror by way of Sam Raimi. Some of the imagery, namely involving hands and crawling things en masse, tapped on personal, primordial fears in ways I’ve never experienced before.

Given the obvious influence of this film and fable on the genre, it’s not hard to trace the branches back to the root, where the same tricks as old as silent films bored into somebody else’s brain and festered in their own work.

It does not ruin any of the fun to say that Khoma pays for his sins. Despite his best, desperate efforts, he dies. But what’s strange, and reveals Gogol’s long-game ruse, is how. The religion works. The magic words are magic. Khoma only loses the fight by looking at something he shouldn’t have and scaring himself.

“Khoma was such a fine, young man,” toasts one of his surviving friends, who also bothered the crone but stopped short of killing her. His other friend drinks but disagrees. He was alright, maybe even fine and young, but a coward. If he hadn’t been such a chicken, he would’ve made it.

The moral of this story isn’t faith.

It can’t be learned under the phallic tributes to Father God. That’s all well and good and real. But devotion to the divine is no match for red-blooded, human failure. Khoma didn’t die because he wasn’t pious enough; he died because he was just a bad man.

The punchline is that his friends are only better in the eyes of the law. One assumes Khoma imagined it all in a drunken stupor, dying from his own delusion. The other makes something like a joke that’s just as acidic now as it was in 1967:

“Anyone from Kiev knows the women who run the stalls in the market are all witches.”

As advertised, Viy is not based on a true story. As discovered, it’s not even based on a true legend. But with fifty years of convention and artifice between it and us, hiding now among the newer, shinier offerings on Shudder, it means something more.

Viy has become urtext, an ancient-seeming source of it all, weaving unconsciously, even accidentally through everything from The Exorcist to Evil Dead II. Now it is the folklore to be cherry-picked.

Viy has become true legend, in all its simplicity, retold often and exactly as it was seen by so many storytellers since.

Follow Us!