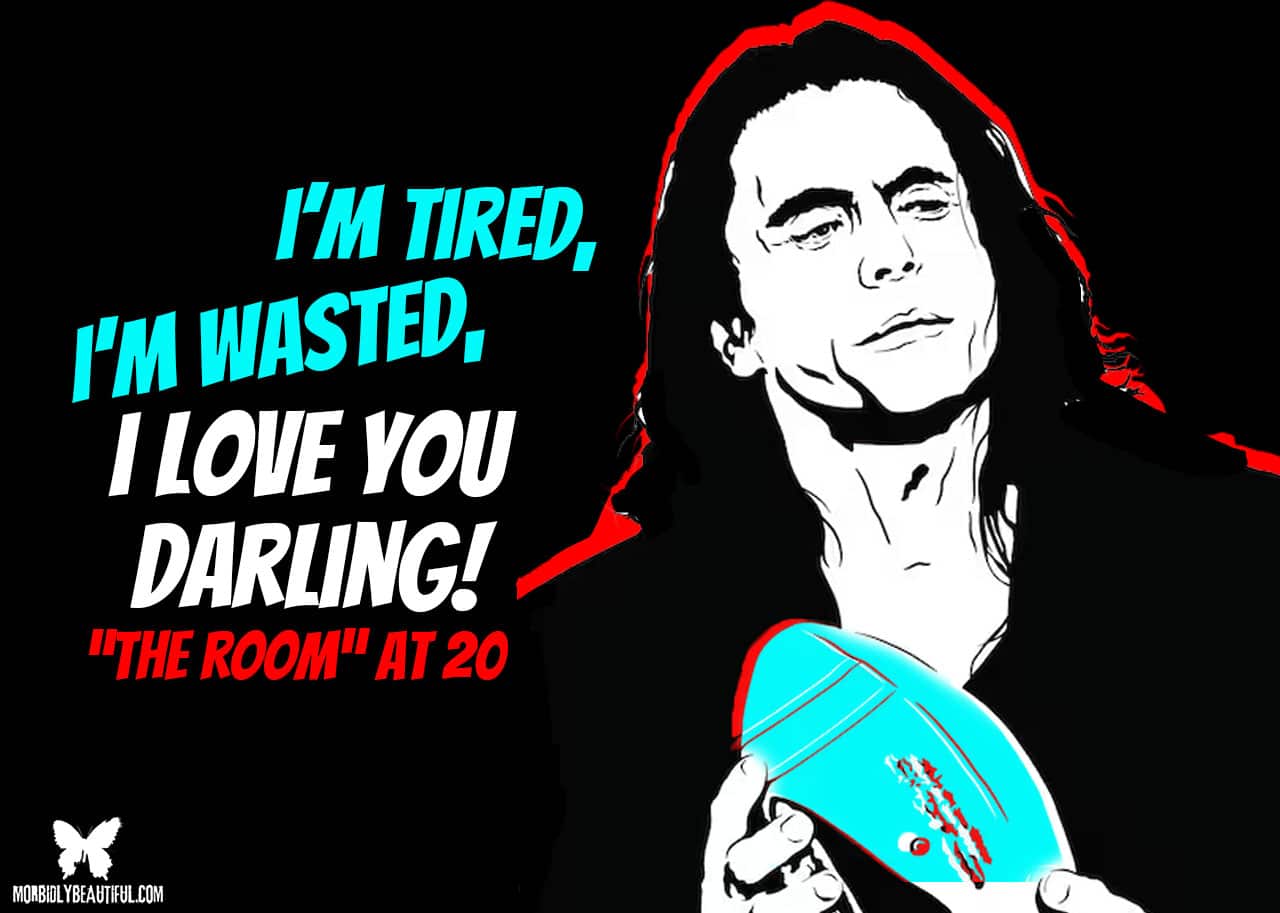

On the 20th anniversary of its inauspicious release, we reflect on the accidental magic of “The Room” and the triumph of the indie spirit.

Everyone has those moments in pop culture history they wish they could have experienced at the time before they became engrained in our collective memories.

Maybe it’s catching the Beatles’ first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964 or visiting Salvador Dali’s “Dream of Venus” pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. Or perhaps it’s sitting in a movie theater in 1977, hearing Darth Vader’s labored breathing for the first time.

There’s something magical about being able to experience a work of art completely fresh, without the baggage of cultural significance and expectations accrued over time.

For me, oddly enough, one of those moments would be having the chance to see Tommy Wiseau’s craptastic masterpiece The Room in its initial theatrical run in a single LA theater in 2003, 20 years ago.

Long before co-star Greg Sestero’s tell-all book and its subsequent movie adaptation and before its absorption into the alternative culture at large. Before its creator became a living meme, leaning into his reputation as a trash icon, back when he still hoped his film would launch a more respectable career. In short, before most of the world had any idea what the hell it was.

The cult of The Room began slowly, with a handful of intrepid moviegoers and critics who braved the theater and began talking back to the screen, creating their own in-jokes like a Rocky Horror for the new millennium.

In the coming years of midnight screenings, it expanded to encompass Hollywood fans like Paul Rudd, Patton Oswalt, Tim and Eric, and Seth Rogen, who would later co-produce the film about its making.

In the early 2000s, our internet-soaked era was still in its infancy, and the film’s following mainly grew through word of mouth and early reviews whetting the appetites of bad movie fans.

Through the late 2000s and early 2010s, its cult became supercharged by the domination of social media and platforms like YouTube, where highlights from the film circulated to the tune of millions of views, climaxing with the release of Sestero’s book The Disaster Artist in 2013 and its film adaptation four years later.

Somewhere along the line, Wiseau attempted to lean into the criticisms and claim the film was a black comedy.

He tried hard to convince us that those roars of laughter from the audience were intentional, but I don’t think he managed to fool anyone. His attempt at a wrenching, erotic drama had failed miserably. In its place, an unintended comedic masterpiece was born.

The making of The Room has been well-documented, first by journalists and finally by Sestero and his co-writer Tom Bissel and in James Franco’s film, so I won’t bother rehashing all of that here.

Its particular anti-charms — its bewildering acting, alien dialogue, softcore porn cinematography, deeply unsexy sex scenes, odd digressions, and mid-movie casting changes — are also well-known. It’s one of the rare movies that truly has to be seen to be believed, and plenty of people have seen it by now.

So what is there to say about The Room 20 years later, when its charms have been dulled by age, its surprises spoiled by years of repetition and copious meme-ification? Is it even worth saying anything about it anymore?

For a “so bad it’s good” movie to reach true transcendence, there must be a dissonance between its intention and its reception. Most of the greatest bad movie classics — your Plan 9s and your Birdemics, or your Cats and your Welcome to Marwens, to name a couple more recent examples — didn’t set out to make something that would be enjoyed through a thick haze of irony (and likely weed smoke).

Some filmmakers, Wiseau included, eventually embraced the playful mockery. But despite his later claims, part of why The Room became such an underground success was because he had clearly intended it to be taken seriously.

Some movies manage to succeed at being bad on purpose, but their charms are different; their makers are in on the joke, and the audience knows it. Viewer and maker are on equal footing. It’s undeniably a bit mean-spirited, but the fact that these filmmakers fell so far below their intended mark is a big part of what makes the work so much fun to watch. It’s a lot harder to laugh at someone’s folly when it at least appears they’re laughing with you.

But I don’t think this dissonance is the only reason The Room was worth watching 20 years ago and why it’s still worth watching today.

Wiseau didn’t just miss the mark, he missed it so completely that he managed to hit a bullseye two counties over. It’s one of the rare movies that manages to totally subvert our expectations of what a movie even is, coming out the other side like something from a parallel dimension.

Like a Cenobite offering transcendence through mutilation, Wiseau took us to a stratosphere most of us didn’t even know existed. He had such sights to show us — and show us he did.

Even with other movies of its ilk, ones with similar failures and a similar distance between ambition and execution, few of them manage to grasp what Wiseau accidentally stumbled into.

Birdemic may be even cheaper and uglier than The Room, but its badness still feels rooted in a reality that most of us can understand.

It’s easy to laugh at an epic bungling like Cats, with a budget in the tens of millions and a cast of A-list celebrities, but we can recognize that the movie was made by people who were at least competent in their fields, even if their competence somehow still added up to disaster.

With The Room, there’s none of that. Its story beats may be familiar, even elemental, but its execution is unlike anything else.

On the occasion of The Disaster Artist’s publication in 2013, writer Adam Rosen released a piece in the Atlantic arguing that movies like The Room deserve to be considered outsider art, that label typically applied to paintings and sculptures made outside of established artistic schools and traditions, and I think that’s an interesting way to think about it.

Movies require such vast resources that most people outside the industry have little chance of breaking in.

Wiseau, with his own mysterious source of seemingly endless funding, was able to skirt the mainstream establishment and make a film completely on his own terms, without the meddling of financiers who would’ve no doubt tried to curb his eccentricities.

While most of us don’t have 6 million dollars to sink into our passion projects, the fact that Wiseau was able to pull it off is weirdly inspiring.

Sure, a lot of us probably wouldn’t want a career built on being the butt of the joke, but it’s still more than most of us get.

In an era where Hollywood productions become safer and more cookie-cutter predictable, recycling the same handful of fiercely guarded IP over and over, singular works of vision like Wiseau’s — spectacularly ill-conceived though they may sometimes be —a re becoming vanishingly rare.

I can’t quite remember where my own experience with The Room began, but I think it was late in high school or early college, about five years removed from its initial release, when it was being lifted up by comedians and bad movie geeks, but before its reputation went mainstream. My main group of high school friends, many of whom I’m still close with to this day, were something of bad movie geeks ourselves, trolling the aisles of our local video store, looking for the wildest, wackiest schlock we could get our hands on.

But The Room wasn’t exactly likely to end up on the shelf at Hollywood Video.

I remember watching the aforementioned YouTube compilations over and over, reveling in the bizarre display of filmmaking ineptitude, eager to experience it in full long before I actually did.

Regardless of when and where I first saw it, I will forever associate The Room with that time of transition in my life, on the cusp of stepping out of my predetermined existence, making the first unsteady motions into adulthood. Back when everything, even making a movie, seemed possible.

It may not feel recognizably human, but maybe The Room tells us something about humanity — our desire to create in spite of the obstacles and our lack of skill, our need for communal experiences, and the sheer joy of a “good” bad movie — all the same.

Follow Us!