“Frankenstein” gives life to a misunderstood monster, a fallen angel turned malignant devil, and forces us to confront our own humanity.

As I was watching the grotesquely beautiful and utterly riveting new psychological horror film directed by Laura Moss and written by Moss and Brendan O’Brien, Birth/Rebirth, inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, I felt compelled to not only review the film but to further expound on the novel’s enduring influence.

I wanted to explore the rich thematic tapestry that provides a fertile ground for the birth of new interpretations and the rebirth of concepts that never feel tired or outdated.

Although published more than two centuries ago, the themes in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein remain as eerily relevant today as the day it was published.

The first major work in the science fiction genre, focusing on science as a means to create life, Frankenstein served as a framework for narratively examining the morality and ethics of the experiment and experimenter.

One of the most influential literary works of all time, Frankenstein is most notable for bringing to life two unforgettable archetypes: the shunned creature and the morally gray mad scientist. It’s these larger-than-life depictions of hubris and horror, and ambition and abandonment that lurched off the page and onto stage and screen — forever reshaping not just horror but cinema itself.

It’s a story about the pursuit of scientific advancement as it collides with obsessive ambition, a lack of caution and care for others, and a failure to consider the morality of playing god — seeking power over life and death.

But the brilliance of Frankenstein is that it is far from black and white.

Science and medicine are inherently an attempt to not just understand our world but exact some control over it.

Advancements to significantly prolong life (the average life expectancy in the U.S. in 2023 is roughly 79 years; in 1816, it was somewhere between 35 and 55, depending on the data examined and a variety of socio-economic factors) are widely viewed as reflecting great progress and a positive effect of mankind’s relentless pursuit of knowledge.

The pursuit of cures for diseases and illnesses, especially those that cause great suffering and/or premature death, is considered one of the most noble pursuits of mankind.

But in our complex modern world of political warfare and misinformation, even the seemingly selfless pursuit of life-saving medicine can be fraught with mistrust and criticism. You don’t have to look far for a recent example, as we’re all still feeling the effects of America’s response to COVID and the division it stirred among those who hailed the vaccine as a miracle of science and a heroic effort to save lives versus those who feared the cure more than the disease and questioned the integrity and voracity of politicians, scientists, doctors, and government officials.

“When falsehood can look so like the truth, who can assure themselves of certain happiness?”― Frankenstein

And still, staving off death for as long as possible is a goal most humans aspire to. But how would we respond to a possible cure for mortality itself?

If death could be cheated indefinitely, would we find comfort or terror in a revelation that fundamentally alters our entire framework for existence? Would we consider this a miracle of science worthy of gratitude and exaltation?

Or would we shriek in collective terror and outrage over the kind of life-altering advancement that carries staggering implications and repercussions (career and wealth planning, environmental impact, mental health, and spiritual/religious and ethical considerations, to name a few)?

And would our response to such a brave new frontier shift, as so many things do, when the life that gets saved is our own or someone we dearly love?

How many of us claim the moral high ground only when we have no real stakes in the game? It’s the essence of an argument about choice and autonomy in an age of an overturned Roe v. Wade, where decisions about a woman’s right to control what happens to her own body — and determine if and when she becomes a parent — are made, more often than not, by people who will never be forced to personally reckon with such monumental decisions.

When it comes to great scientific advancements, the theory of what such achievement might mean for humanity often deviates wildly from the reality of its application.

Whereas intent is often noble, execution is often problematic at best — immoral and unethical at worst.

Christopher Nolan’s critically lauded but controversial film Oppenheimer does a masterful job of exploring this notion. We often get so caught up in the idea of whether or not we can do something that we rarely stop to contemplate if we should.

And even if the original intent is grounded in a sense of morality and a desire to protect humanity, history has proven time and time again that, ultimately, knowledge is power — and power so often corrupts.

Though, as Oppenheimer reveals, a lack of knowledge is just as dangerous as the aggressive pursuit of that knowledge. If the power to end the world is discoverable, isn’t it better if that power rests in the hands of the “good guys”?

Except, when it comes to the pursuit of power, domination, and control, there’s no such thing as good guys and bad guys. There are only those who wield power — and, therefore, control destiny — and those who suffer at the hands of that power through oppression, fear, destruction, and devastation.

If the end result is something of noble intent — the power to save lives, for example — do the means, however questionable and potentially horrific, become justified? If more people thrive than suffer, does that excuse the suffering? If the reward outweighs the risks, is it worth it? What’s an acceptable loss in pursuit of great gain?

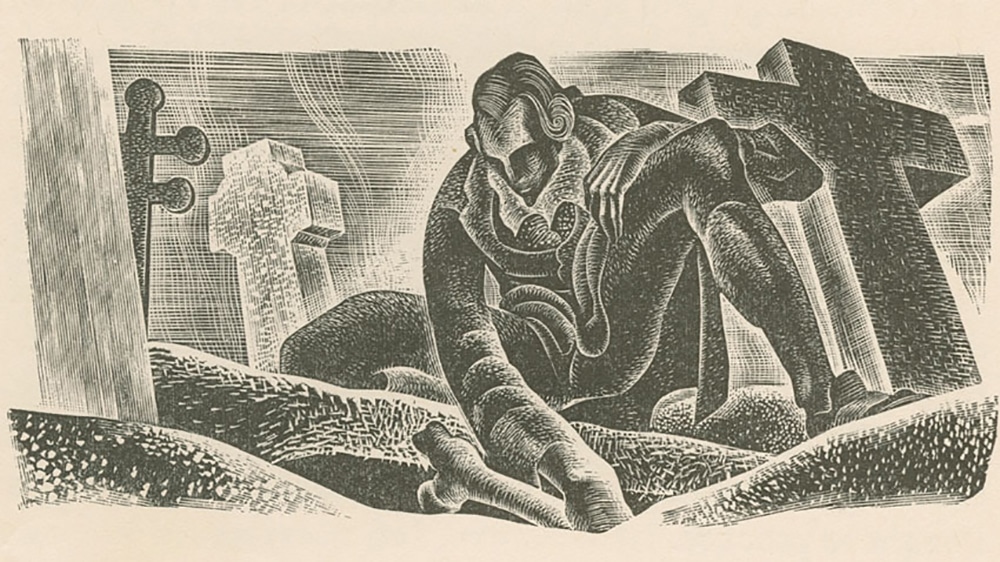

The ideas examined in Frankenstein were haunting and unnerving back in 1816 when young Shelley first penned her gothic masterpiece while summering in Switzerland at Lord Byron’s palatial Villa Diodati estate.

The well-educated daughter of two influential writers, acclaimed journalist and political philosopher William Godwin, and celebrated feminist author Mary Wollstonecraft, Shelley populated her novel with the popular intellectual discourse of the era.

Contemporary debates raged on the nature of humanity and whether it might be scientifically possible to revive the dead.

But as the frontiers of our knowledge have pushed further and further, the unintended consequences of science and technology — and their effect on both humanity and the planet — have become a timely topic of debate and a core pillar of modern anxiety.

Throughout the years, Frankenstein has evolved to resonate far beyond the ramification of re-animation.

It has come to embody our cultural fears in the face of genetic engineering, transplantation, artificial intelligence, robotics, virtual reality, synthetic biology, and more. At the core of Frankenstein are big questions about what it means to be human and the implications of those questions that still permeate today’s Modern Prometheus.

For 200 years, Frankenstein has inspired an endless array of interpretations and parodies.

These include the origins of the moving image itself in Thomas Edison’s horrifying 1910 short film Frankenstein. Both Hollywood’s Universal Pictures and Britain’s Hammer series owe a huge debt to the archetypal monster tale, as do the generations of horror filmmakers influenced by these paragons of classic horror.

From The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Tim Burton’s Frankeweenie, artists continually find new ways to mine the beauty and horror of this enduring tale.

The culturally significant characters and themes have inspired comic books, video games, spin-off novels, television series, and music.

As a parable, the novel has been weaponized for and against arguments around slavery and vivisection in the British Empire. It’s been used to debate the wages and spoils of progress and has fueled arguments over religion and atheism. Its central themes have been invoked while discussing everything from the atomic bomb to stem cell research to AI.

Despite a clear examination of the dangers and morality of overreaching, Frankenstein is not, as it is often interpreted as, a condemnation of science and progress. It’s much more complex and meaningful than that.

In fact, the reason the story has been so rich for centuries of mining and continuous re-interpretation is that it is purposely open to interpretation and replete with many themes that transcend the idea of man versus monster and the perils of progress.

As much as the story is about a man playing god and accidentally giving birth to a monstrosity, it’s about the pathos of the creature itself — discarded by his father, unloved and unwanted, misunderstood and hated for the tragedy of his birth.

Though he may have begun as a beautiful ideal, the monster is terrifying to behold. This vision of monstrosity and madness became the quintessential view of Frankenstein as shaped by Hollywood.

But Shelley also invokes the myth of human creation, including a quote from Paradise Lost in the epigraph:

“Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay / To mould me man?”

Though his cinematic transformation into a lumbering, hulking monster is what is immediately conjured when thinking of Frankenstein’s monster, it’s ultimately the creature’s tragedy and his humanity rather than his monstrosity that makes him so compelling and enduring.

When considering the origin of the creature, there’s an injustice to his existence and his persecution related to the circumstances of his birth, which has many parallels in modern-day classism and racism. It speaks to our responsibility to our children, to the outcasts and outsiders, and to those who don’t conform to conventional ideals of beauty.

While Hollywood made him a mindless mute, Shelley gave the creature a voice as one of the three narrators in the book, as well as a literary education.

He is able to articulately express his thoughts and desires. And his lament over his tortured existence is haunting.

“Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.”

The creature’s first and most devastating rejection comes at the hands of his creator, his father, his god. It’s a heartbreaking example of parental abandonment that sets the creature up for a life of anguish and alienation.

As this wretched, unwanted child is mercilessly thrust into a society that recoils from the very sight of him, his rejection and inability to find compassion and comfort is what ultimately turns him into a monster.

There’s a good reason people so often mistakenly refer to the monster as Frankenstein rather than the doctor. Frankenstein’s monster is born out of his self-centered obsession and his privileged perspective, leaving him well-meaning but ignorant of the consequences of his actions and their impact on others. He is a being of Frankenstein’s making, both literally and figuratively.

This a tale that begs the question: who is the real monster?

Is it the accident of creation, born wrong and discarded as an abomination rather than a victim of circumstance? Or is it the man whose blind ambition resulted in devastating effects that he never truly accepts blame or atones for?

Ultimately, it’s perhaps most helpful to view the timeless tale not as a story of good versus evil but rather of choices and consequences.

It’s not man versus monster. It’s man’s monstrosity. It’s not a condemnation of science. It’s an exploration of man’s inherent need to create, rivaled only by his hunger to destroy.

When Shelley wrote in the preface to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein, “And now, once again, I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper,” she could not have imagined the ways her creation would go on to shape culture and society for years to come — even well into the 21st century when a vastly different cultural, social, and intellectual landscape proves the old adage, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Follow Us!