In honor of Black History Month, we explore the origins and evolution of Black representation in Horror — from birth to rebirth.

There is a popular phrase that is casually thrown around when referring to film and its place in society. That phrase is, “It’s just a movie.” I have always held cinema in high regard as not just a form of entertainment, but a transformative art form that mirrors our society. And in my opinion, no other genre of film achieves this feat quite like the horror genre.

Horror was a staple within the film industry from the very beginning, with films like the 1896 shorts House of the Devil and A Terrible Night from legendary filmmaker Georges Méliès. As a brand-new art form, everyone around the world was thrilled about the possibilities of this wonderful new experience in entertainment.

Art should be accessible to anyone and everyone. And while cinema was accessible to most, the characters and events portrayed on screen were only limited to very few points of view.

For the most part, during cinema’s early decades, white actors dominated the silver screen. If a character was meant to be a person of color, they were portrayed by a white actor in heavy makeup. This travesty obviously occurred within the horror genre as well.

It was not until the era of the Civil Rights Movement in America when a revolutionary film was released that changed the landscape for wider representation in cinema.

That film was George A. Romero’s zombie classic, 1968’s Night of the Living Dead.

This film was so important for representation due to its unique protagonist at the time, a more than capable black hero named Ben, played by Duane Jones in an unforgettable performance. Just as America was witnessing the emergence of black heroes like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and Rosa Parks, American cinema experienced its own hero with Ben in Night of the Living Dead.

In the pivotal film, Ben leads the charge against the zombies and ends up the sole survivor. In the very end though, Ben is mistaken for a zombie and killed by a white mob.

Night of the Living Dead was meant to replicate the feel of the black-and-white television footage of protestors in the Civil Rights Movement.

Ben’s shocking murder at the end of the film is specifically meant to reflect the racial injustice that was occurring in America at the time.

It begged the question, “Who are the real monsters?”

In her article, “Black Masculinities and Postmodern Horror: Race, Gender, and Abjection”, Penn State University’s Jessica Baker Kee writes about the film’s ending:

“The armed lynch mob first appears walking slowly in a ragged line across the field, visually indistinguishable from the zombies’ chaotic collectivities portrayed throughout the film. The casual savagery with which they finally dispatch Ben (“that’s another one for the fire, boys”) is presented as no less horrific than the zombies’ implacable bloodthirst.”

In the following decade, the blaxploitation genre became highly popular, with films like Shaft and Super Fly.

Regarding the horror genre, 1972’s Blacula was perhaps the most famous horror film of the blaxploitation era of the early 1970s. Blaxploitation may have been important and influential for black representation in American cinema, but the genre portrayed an inaccurate, over-the-top fantasy of black American life.

During the 1980s, the slasher film craze sparked by Halloween and Friday the 13th did no favors for black representation either. During this era is where the “black person always dies first” trope began. How far black representation in horror had fallen since 1968’s Night of the Living Dead.

In the early 1990s though, like Night of the Living Dead three decades prior, one film stood out as a trailblazer of black representation in American horror. That film was Candyman, starring Tony Todd as the titular slasher (Todd also starred as Ben in the remake of Night of the Living Dead two years prior to the release of Candyman).

Candyman was unique at the time due to its horror being overtly drawn from the black experience in America.

In the film, Candyman is the ghoulish specter of a man who was the son of slaves, and after impregnating the daughter of a rich white man, was lynched by a white mob. Sound familiar? In the present day, grad student Helen Lyle, played by Virginia Madsen, begins to investigate Candyman and his legend. This leads her to Chicago’s former Cabrini-Green housing projects, where the myth of Candyman prevails.

Slavery will always be linked to black America. It is America’s cardinal sin, whose effects are still being felt today.

A significant percentage of black Americans still live in housing projects, and one could trace this disparity back to slavery. Making Candyman a lynched son of slaves who continues to haunt a housing project long after his death speaks volumes to a considerable percentage of black America.

The fact that Candyman was lynched by a white mob, like Ben in Night of the Living Dead, is also significant. One can just read the news for proof of this sadly still taking place in America.

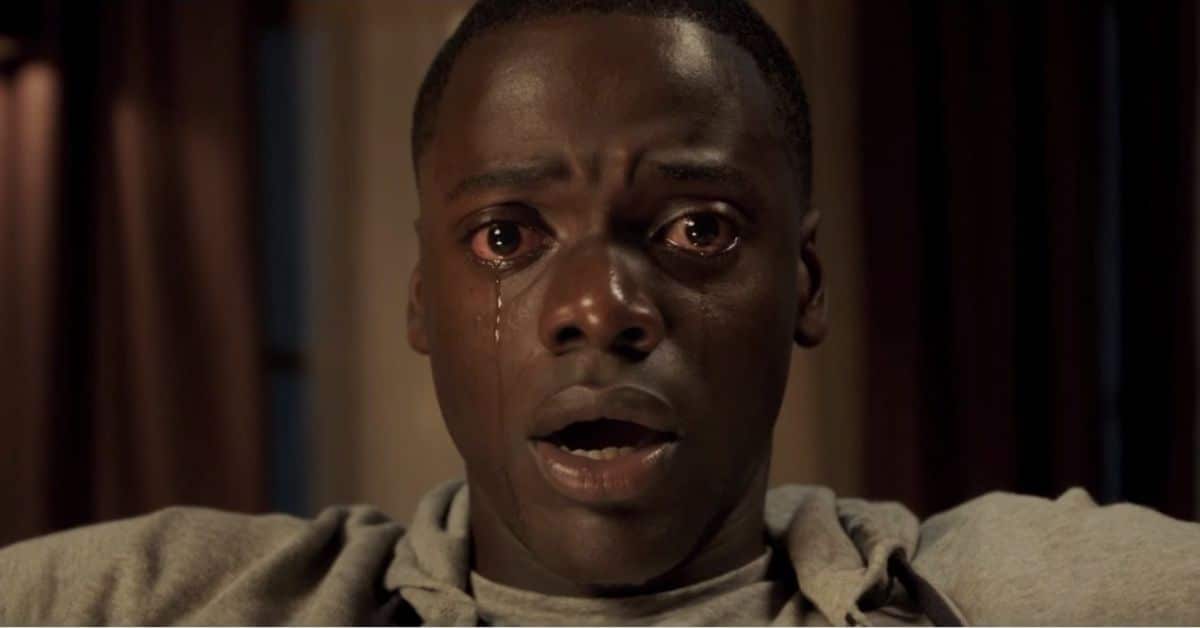

One may realize that, in recent years, Hollywood’s black horror films have been more mainstream and represent black America quite genuinely. This is largely due to the efforts of filmmaker Jordan Peele. You may be familiar with Peele as one half of the comedy duo Key & Peele, but more recently Peele has demonstrated his skill behind the camera with his groundbreaking films Get Out and Us.

What makes Get Out and Us so important is that their horrors speak to all of black America.

Peele’s films explore universal black issues and feature a predominately black cast and crew.

Candyman himself Tony Todd said in Candice Frederick’s “The King of Black Horror” article:

“When I started in this business, I would show up on set and not only would I be the only black actor, I would be the only black person in jobs that anybody should have the opportunity to do if it wasn’t for nepotism. Now it’s changed.”

This major factor is what sets Peele’s films apart from many of the most famous black horror films of the past. They explore real issues facing all black Americans and they are made purely from the black American perspective.

The author of Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present, Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman, disclosed in Moderate Voice:

“Black actors have always had a role in horror films. But something different is taking place today: the re-emergence of true black horror films. Rather than simply including black characters, many of these films are created by blacks, star blacks or focus on black life and culture.”

Black horror is not necessarily experiencing a renaissance as it is experiencing its true and rightful birth.

Black American horror has finally reached the point that it deserved to be at from the very beginning.

Black artists have stories to tell just like everyone else. It is high time that those stories are told the way that they were meant to be told. I hope that prospective filmmakers and working filmmakers reading this take note and truly understand why representation in cinema is so necessary for society.

Remember this statement from Professor Evelynn Hammonds as she wrote in Dr. Kinitra Brooks’ article “Finding the Humanity in Horror: Black Women’s Identity in Fighting the Supernatural”:

“…in overturning the “politics of silence” the goal cannot be merely to be seen: visibility in and of itself does not erase a history of silence nor does it challenge the structure of power and domination, symbolic and material, that determines what can and cannot be seen.”

Still think they’re just movies?

Follow Us!