Bound by shared lesbian subtext, “CAT PEOPLE” and “THE SEVENTH VICTIM” subtly explore the conflicts of queerness present in early 20th Century America.

In early 20th Century America, homosexuality was far from socially acceptable.

Though the Roaring Twenties had seen a cultural shift that questioned traditionally defined sexuality and gender, it would be another fifty years before queer “behavior” would be decriminalized and homosexuality removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental illnesses.

During these years, queer people found subtle ways to express their identities and all the nuances that came along with them: the desire and the shame, the fear and the joy. Queer artists weaved their truth into art across every medium, from music to film.

One of these artists was screenwriter DeWitt Bodeen.

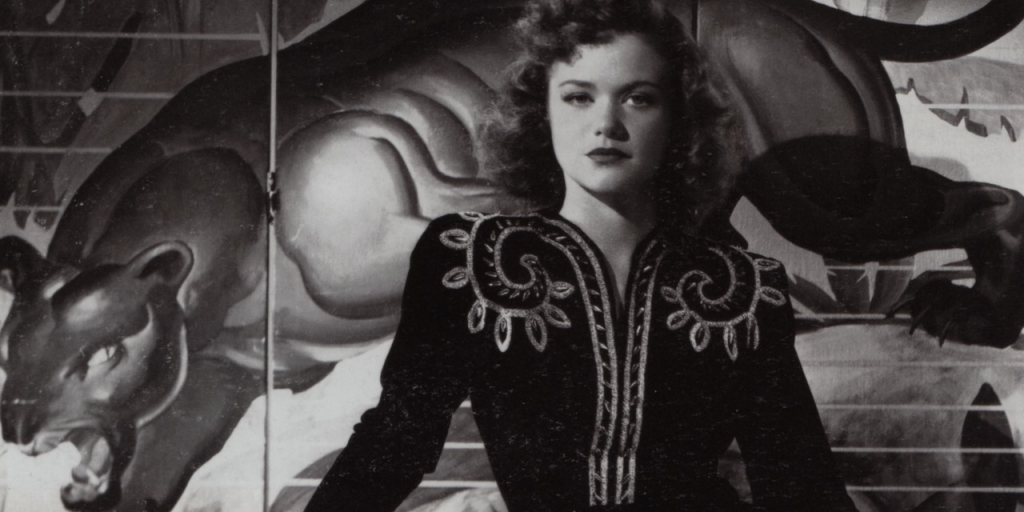

The complexities he must have experienced living as a gay man can be felt in two of his most famous works: Cat People (1942) and The Seventh Victim (1943, co-written with Charles O’Neal). Both films focus on women struggling with secret shame, with the fear of being different and a longing for acceptance.

The two films deserve to be examined together, not only because they were both written by Bodeen and share similar themes, but they also seem to take place within the same universe.

They share a recurring character — Dr. Judd, a psychiatrist played by Tom Conway — who plays a vital role in the journey of both leading ladies (despite being apparently dead at the end of the earlier film, Cat People; maybe the timeline isn’t linear?).

Taken together, these two films create a multifaceted reading of both the internal and external turmoil that has been all too familiar to queer people throughout history, right down to the present day.

Cat People represents the internal struggle, while The Seventh Victim is about the external struggle.

Cat People is about the fear and shame that often accompanies the realization that you are not “normal,” and the deep-seated desire to become normal or, at the very least, perform normalcy, while The Seventh Victim is about the desire for social acceptance, community and belonging, and the threat of ostracism.

Irena Dubrovna is a Serbian immigrant haunted by her lineage. She keeps a statuette of the medieval Christian king who drove the “cat people” from her village, forcing them to find refuge in the mountains, where they thrived for centuries.

Irena is a descendant of these devil-worshipping witches known for their “corrupt passion.” Though they are repeatedly referred to as “cat people,” the community is made up predominantly, if not exclusively, of women.

It isn’t a stretch to read their “corrupt passion” as lesbianism.

Any man who encounters these women meets a grim fate: after having sex with men, a cat woman will turn into a panther and kill him. This seems to suggest that the women use men for reproductive means and then discard them, having deemed them unnecessary for any other function.

The history of these cat women is fascinating, but not explored as deeply as I might like. That’s because the focus is on Irena and her internal conflict, trapped between the past she wants to escape and the future she desires.

She impulsively marries the first person to befriend her in America, an architect named Oliver, despite the fact that they’ve never so much as kissed.

Though Irena has confessed her fears of being “different” and “evil” to Oliver, he vows to make a “normal” woman out of her.

“You’re so normal you’re gonna marry me,” he says, “and those fairytales, you can tell them to our children.”

Irena longs to fill the socially acceptable role of wife and mother, but fears that she cannot. After their wedding, she asks Oliver to be patient, saying that she needs “time to get over the feeling that there’s something evil in” her before she can be physically intimate with him.

After a month of sexless marriage, both Irena and Oliver are miserable. Oliver suggests Irena see a psychiatrist, Dr. Judd, in the hopes that he can “cure” her.

Dr. Judd is the thread that links Irena to Jacqueline Gibson.

The Seventh Victim is about Jacqueline, but the main character is her sister Mary, who is searching for the missing Jacqueline.

Jacqueline sought out Dr. Judd to “cure” her of her depression and suicidal ideation, though, like Irena, given the full context of the situation, this can be read as seeking a “cure” for her queerness. Also like Irena, Jacqueline married a man, Gregory, though she displays very little affection for him in the few scenes they share (and it’s worth mentioning that he eventually falls for Mary).

The Seventh Victim’s plot is somewhat convoluted, taking various twists and turns to dispel the mystique surrounding Jacqueline.

However, her conflict is actually very simple.

Jacqueline joined a secret Satanic cult called the Palladists, hoping they would be her “cure.” When she becomes disillusioned with the group, she leaves and seeks out Dr. Judd, revealing the cult’s existence to him, an act of betrayal punishable by death.

Jacqueline goes into hiding but is eventually captured by the Palladists. Unable to bring themselves to murder her outright, the cult instead tries to coerce Jacqueline into committing suicide.

One member of the group, a young woman named Frances, who was “intimate” with Jacqueline and “loved” her, speaks up against their plans to kill Jacqueline.

But one of the group’s leaders, Ms. Redi, uses manipulative tactics to quell her uncertainty.

She belittles Frances, questions her loyalty, and undermines her feelings for Jacqueline.

As the cult sits and waits for Jacqueline to drink poison, trying to break her will, she steadfastly refuses; it’s only when Frances breaks down and begs her to “just do it,” that Jacqueline finally gives in. But Frances immediately knocks the glass from Jacqueline’s hand and throws herself on her, sobbing, confessing that “the only time I was ever happy was when I was with you.”

The Palladists use the two women against each other, to ensure Frances’ continued loyalty and to push Jacqueline over the edge.

The cult’s brainwashing (as well as Dr. Judd’s psychiatry) contains echoes of conversion therapy in their use of faith as a means to “cure” Jacqueline.

However, in a different light, the Palladists themselves can be read as queer.

At the end of the film, when Dr. Judd condemns them for their “evil” ways and quotes the Lord’s Prayer, one of the group’s leaders asks, “who’s to believe what is right and what is wrong?”

In this moment, the shame that Jacqueline and Irena have felt is shifted to them. They exist in secret, in the shadows, because who they are is not socially acceptable.

Before homosexuality was widely accepted, queer people used coded language to recognize each other in public without giving themselves away to the rest of the world.

The Palladists use a cryptic symbol as their calling card. When Mary asks Frances about the symbol, Ms. Redi furiously reminds Frances, “that symbol is us. She was asking about us.”

In this context, when Jacqueline tells Dr. Judd about the Palladists, she has outed them.

This recalls a scene from Cat People, in which Irena encounters a fellow “cat woman” in public. The woman approaches Irena during her wedding celebration, surrounded by her new husband and their friends (including Dr. Judd), and calls her “my sister.” She has outed Irena.

Being publicly outed is one of the biggest fears that any queer person has at some point in their life.

It was certainly a fear that DeWitt Bodeen was deeply familiar with.

In the 1940s, if his identity became public knowledge, his career would most likely have been over. It’s no surprise that this fear worked its way into two of his scripts.

Ultimately, both Irena and Jacqueline have unhappy endings, but it’s difficult to box either of them neatly into the “tragic lesbian” trope.

Surely their fates are a reflection of Bodeen’s anxieties and fears that queer people, unable to fit the socially acceptable mold of “normal,” might never be able to live happy, fulfilling lives.

But Bodeen does offer a bit of wisdom — and maybe a little hope.

At the beginning of The Seventh Victim, as Mary prepares to leave her private college to search for Jacqueline, a young teacher confronts her and warns her never to come back. She tells Mary, “you have to have courage to live in the world.”

Today, many queer people in America are able to “live in the world,” no longer confined to the fringes of society like the Palladists and the “cat people.”

We’ve shaken off our shadows; I hope that DeWitt Bodeen was finally able to shake off his.

…

Follow Us!