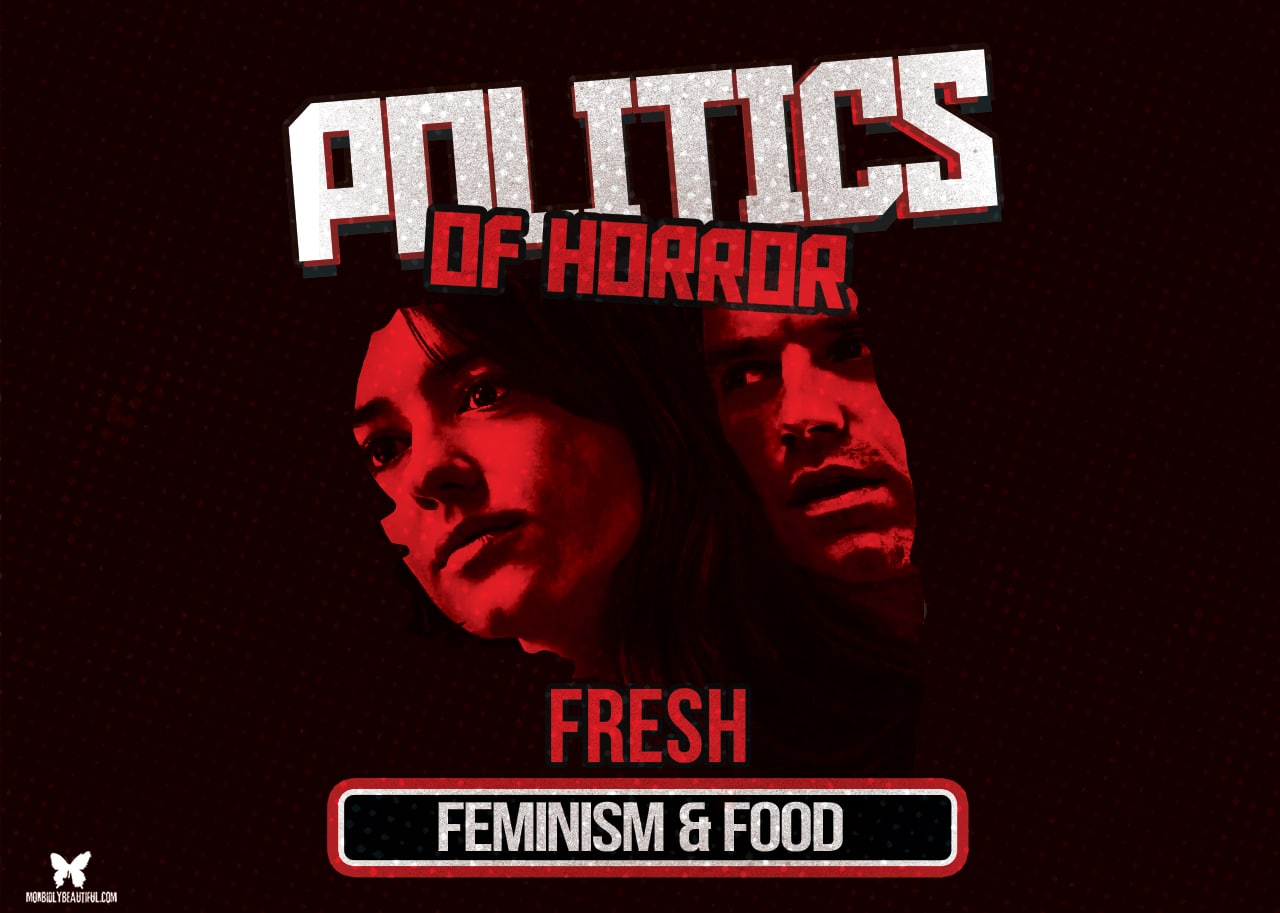

The witty, well-acted “Fresh” is an entertaining treat, but there’s also plenty of chilling meat on the bones of this feminist horror.

Hulu was running hot in 2022 with a spring picture marked a “thriller” entitled Fresh, written by Lauryn Kahn and directed by Mimi Cave. Starring Daisy Edgar Jones and Sebastian Stan, I’d say this falls somewhere between a psychological thriller and a jet-black comedy.

Fresh jumped right into the choppy waters of a squeamish subject with no hesitation and showed us the bleakest side of online dating, where users are all on display to be judged, selected, and sampled.

This is how we find quiet, cool girl Noa, adeptly played by Daisy Edgar Jones, in a sea of left swipes. Despite the failure and difficulty, she trudges on in hopes of finding love.

Fresh opens on the quintessential bad date: a little gross, a little sexist, and with a bit of casual racism tossed at the server.

This man, who obviously believes he is nailing it, has his ideas of being complimentary rooted in “their parent’s generation,” where he believes women tried harder and Noa would look better in a dress! Can’t she see women are all just swimming in their wardrobes these days?

By the time he’s snagged all of her leftovers and graciously let her take a little off her portion of the check, it’s clear this man has struck out.

Even though she graciously rejects her date when there’s just no flame, he launches into the tirade everyone is terrified of but expects from the self-proclaimed “nice guy.”

Leaving Noa visibly shaken, she insults herself for even having the reaction of fear believing a man was, who wasn’t to his credit, following her. This contradiction of feeling you owe your best version of yourself to anyone you cross while also never feeling deserving of boundaries is arduous to watch. It taps into some of the primal feelings you get as a modern woman when you’re alone, and the only thing that you’ve been taught is going to defend you is still a pair of keys or a chaperone.

The stranger danger vibes are high throughout and are director Mimi Cave’s calling card to be careful who you let in.

The grocery store is goofy, but an “organic meeting” there is too perfect a pun to pass up.

Sebastian Stan is charismatic and comedic as Steve, the cotton candy grape-toting suitor interested in getting Noa’s number and her first natural interaction in a while. His sleek attitude, carefree sense of humor, and undeniable smarts (he’s a surgeon, no less) make him leagues above the men Noa has been plodding through.

While she is sold, her best friend Mollie, played by an unreserved, hilarious, and skeptical Jojo T. Gibbs, who has been cynical about all men from the beginning it seems, still has her doubts when a weekend getaway is brought into play after a couple of successful first dates.

This trip sparks it all when Steve finally lowers the facade and makes Noa his prisoner for reasons we couldn’t have imagined: food.

Women as Commodities, Ruling Classes at Work

Women have been a fixture in the flesh trade, so to speak, for as long as it could be done, I imagine.

We are born with an inherent sexual worth and expectation placed on us, as well as the idea that, for a certain number of years, what we wield can be monetized. However, this isn’t prostitution, which can be a woman’s choice; this is something akin to human trafficking with even darker undertones.

The way Steve hunts is nefarious. He is a chameleon himself, but he has a particular type of prey he looks for in the opposite sex: the workaholic, fewer friends, even less family, disenfranchised by the empty dating scene.

He studies these women to bring them close and, eventually, get them close enough to trap and slowly pull apart like the tendons of a pork loin.

The women before Noa, in their respective boxes with photos, are a gallery of slaughtered animals to Steve, and this is just his trophy box. His job is to send other trophy boxes of the same type to like-minded men who share his taste — and his tax bracket.

Looking at statistics, the Office for Victims of Crime puts the number of people being trafficked at approximately 600,000-800,000 a year, with 70% of the victims being female and half being children, most of which are destined for the sex industry.

“Are you going to rape me?” Noa asks, as this seems to be the worst scenario.

The answer is somehow more horrifying than the default thought a woman has in this situation.

This is a statistic that hits close to Fresh’s mark, as all of the victims being taken and sold are women; there is only a market in that sick world for the flesh and belongings of women.

While I’m sure with Dahmer fresh in everyone’s mind that there’s a market for vulnerable male targets as well, the statistics are overwhelmingly in favor of a victim being female for these types of crimes involving kidnapping and sale.

Each buyer of whoever is on Steve’s menu is not just receiving meat — they’re receiving personal items taken and curated by Steve for the buyer to get an experience of just who that girl was.

“The one percent of the one percent” is the market for Steve. They have enough money to buy whatever they want, so they choose the most taboo things they can reach for. “This meal is about $30,000,” Steve says of a small plate of pasta adorned with a single ball of meat. I can only imagine what an entire package cost.

We get small pictures of these only male buyers gorging themselves on women’s flesh, as Steve explains that not only is there not a market for male meat, but that female meat tastes better, in his opinion.

He created a name for himself in these elite circles through his brutality and willingness to tap into the dark psyches of the rich and powerful. An elite himself, a surgeon by trade, Steve didn’t need to get higher to the top for respect; he had the education, the house, and the money before you add in the exorbitant extra income from his side business.

You can never have enough money, I suppose, and if he aspires to be like his clients, then he must sell high and climb towards absurd wealth that allows him this power.

Feminism, Friendship, Failure? Gender Expectations and Possible Victim Blaming

While this film is half feminist beat down on a culture that says women are the market for violence and half a comedic exercise in how light-hearted you can make your meals, Fresh does leave some things to be pondered.

Feminism and female comradery share a lot of space here.

The girls trapped within the walls and the messages left in magazines from previous victims offer an attempt to reach out to inspire.

The fact that Noa landed Mollie into a dangerous territory from her wanderlust is frustrating, but what bothered me most was the relationship the girls faced with the stone-faced character Ann (Charlotte Le Bon). She is morally uncertain at best and directly quoted as “part of the fucking problem” at her worst.

Ann is presumed to be a former victim, as during a parallel scene showing just how spry and happy Steve is, we see that Ann is missing a leg, luckily just that. While a rendition of Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day” blares, we can’t help but wonder if this is the perfect life that Ann imagined when she negotiated her way into Steve’s world.

Can victims really find their place among the victimizers?

Once more, does Ann owe a duty to those paying for her lifestyle, especially once Steve is out of the picture?

Her willingness to commit acts against captives or those trying to intervene for good is shocking, to say the least. Even when the ring leader is taken out of the equation, Ann still seems enraged and determined to dispatch these girls, but why? At what point does she owe it to herself and the girls to extend a hand for help instead of to lock the door behind her? Or is the fact that she escaped and knows this as her only means of survival enough that her actions could be dismissed as psychological damage from years in marital captivity?

She’s never explained enough to say, but the surviving girls don’t give her much chance to as they see she’s no ally.

Are women in this scenario obligated to other women?

The Familiar “Final Girl”

We are so familiar with the concept of the final girl that when a basket of them lands in our laps, we don’t really think about it that much anymore.

You don’t hear the terms “final boy” or “final man” often, if ever.

The term “final girl” itself was coined in the ’90s by author Carol J. Clover as she studied the horror films of the ’70s and ’80s, particularly slashers. As a plot device, it is so reliable that it has become labeled a trope. The final girl design sets the characters up to be taken one by one so the final (usually female) character (or, in this case, multiple final girls) can either thwart the evildoer or escape.

There are exceptions, as the female survivor needs to appear incorruptible or morally pure — making examples like Psycho’s Lila Crane into a “female survivor” rather than “final girl” as she’s a morally ambiguous character.

Another, and possibly the most famous example of a final girl given help, is Laurie Strode, portrayed by Jamie Lee Curtis, who is aided in her escape from Michael Myers.

The fact that escape or survival depends heavily on virtue — and that this appears only to target female characters — makes the argument that the 80s was a time of more “progressive horror filmmaking” a difficult one.

More female inclusion and a lasting character for sequels meant more opportunities for women to star.

However, even when the female character is victorious, endings like that of Halloween and Black Christmas leave the character’s fate in doubt and leave the danger still looming.

Noa and company might have just barely made it out, not intact but still alive, making them, in my opinion, final girls nonetheless.

Noa, unfortunately, has to use her sexuality, smarts, and comradery from girls, current and past, to seduce Steve into believing she’s his final girl, in a way. The fact that the burden is on the women to save themselves and that no one is even looking for them is disheartening. Equally disheartening is the fact that these women are getting weaker by the day and sinking deeper into Steve’s dungeon by the second.

Fresh‘s wild ending sequences with a dance number included reminded me of Ex Machina’s surprise dance number, showing how capable men are of exerting their will over female subjects they create or procure, using them as entertainment.

My question is, why is it only Noa who is targeted by Steve?

She is the only girl, as one of her fellow captors points out, who is known to have slept with Steve. No judgment, though, right? It needs to be thrown in so we don’t jump to victim blaming.

While three girls walk free at the end, only Noa is seen to have “sacrificed her virtue” in spite of the fact that Steve’s fascination with her was what allowed her to fight back not only emotionally and psychologically but with his trust, close enough to land devastating physical blows and make moves to free her fellow captives.

Fresh swivels between the disturbing and the absurd.

It’s performances like Steve dancing, hammering away in the kitchen to the beat of Animotions Obsession, trying on bras, and shooting bags of meat like basketballs into boxes that keep your mouth hanging open.

The film’s use of songs like this, along with very human feeling dinner encounters where Daisy Edgar Jones sparkles, keeps Fresh, and its title villain, from getting too dark to stomach.

As a whole, the film is a feminist knockout with enough gross, strange, and eccentric to keep a viewer engaged.

With powerhouse performances, Sebastian Stan dons a mask of cold apathy, and Daisy Edgar Jones one of intense determination.

I highly recommend this film if you’re feeling a little girl power in you, as these ladies aren’t one to lie down and take it — and they’re up against some fierce, starving competition.

Speaking to victims of trafficking and women and men who have been used as only meat, Fresh shines a light on thriving as a survivor, being the perfectly imperfect final girl, and showing audiences that ladies bite back, too — especially when you tell us to smile.

Follow Us!