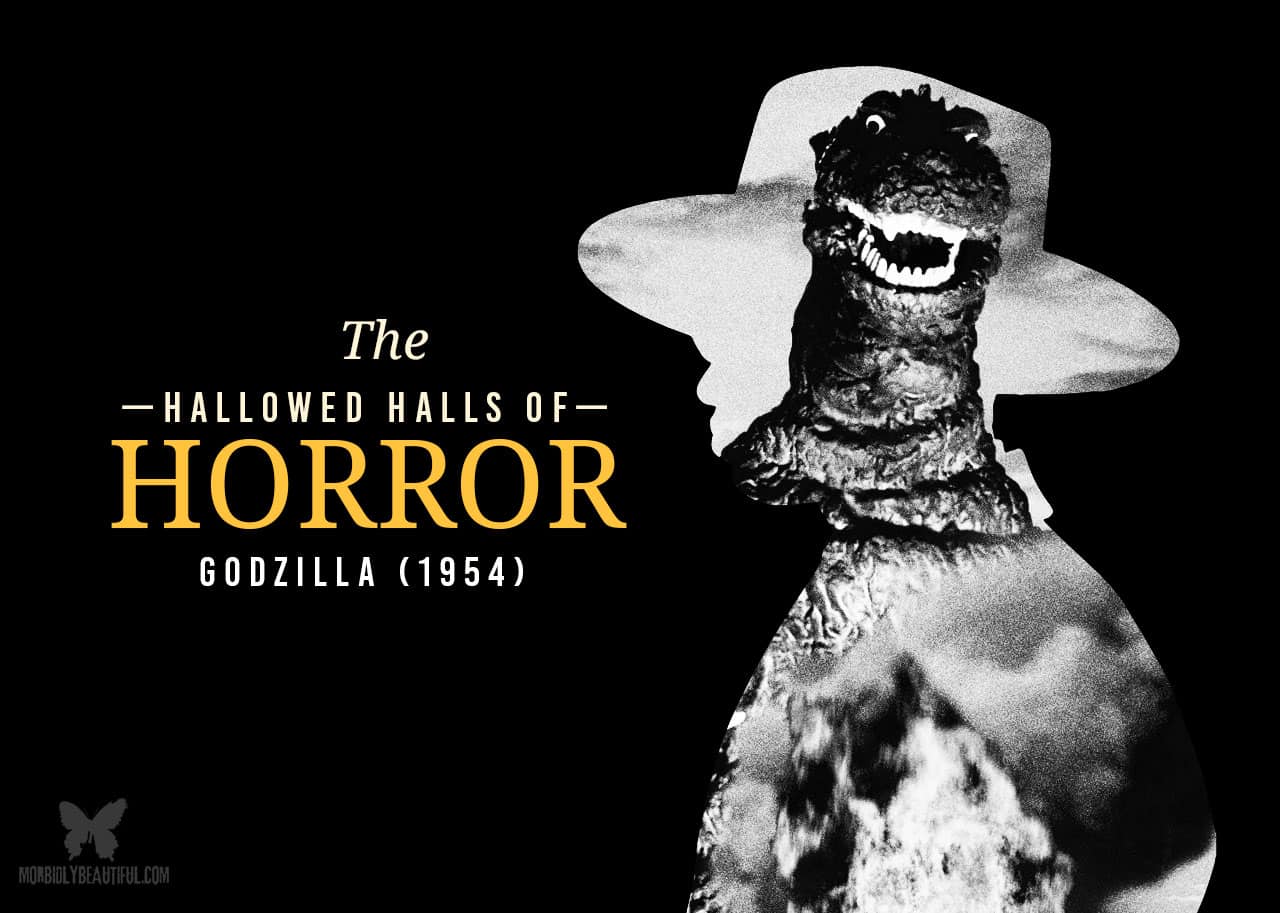

As we anticipate the return of Godzilla to the big screen, let’s explore its importance to both film and world history, beginning with its origin story.

There is no bigger metaphor for the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki than Godzilla. And it had to be the most succinct metaphor, because even after the horrific effects the bomb had on civilians, the Japanese weren’t even allowed to cope with that trauma due to US occupation.

The US wouldn’t end their Japanese occupation until 1952, a whopping seven years after the bombing. In that timeframe, all art related to the bombing was snuffed out. The US knew that coping with the horrors of turning people into shadows on the sidewalks would simply make the Japanese stronger. If they were able to fester in their rage, or process the death and destruction, they might regroup and deal the States some justice.

And it worked.

By the time the soldiers left, the artists and thinkers who wanted to talk about the bombing were given little to no attention. People wanted to forget and move on to less painful things. Japan as they knew it was shattered, and dwelling on it wouldn’t help.

People who had been affected by the radiation, but not killed by it, were dubbed “Hibakusha” or “bomb affected”, and were immediately cast off to the side.

These people would show the government what exactly exposure could do to a person, and outside of that, they didn’t matter. Even now, those who were “bomb affected” aren’t given attention.

The Japanese might have never been able to truly look their horrific past in the face if they had not been exposed to a second round of trauma and terror. The US would once again gave the country a real reason to worry about radiation. In March of the year that the occupation ended, the US military ran nuclear tests on Bikini Atoll — dropping on a boat of fisherman and leaving the people on shore, whose main source of protein was fish, scared to eat anything from the potentially poisoned ocean.

It would be years before seminal works were written about Hibakusha or their struggles.

One of the most vivid memories I have from my undergraduate studies is reading a story about a woman who was unable to give birth because of the after effects. She looked normal, still beautiful, with plenty of men fawning over her. But all of her children died in the womb. She would keep their remains in jars, creating a shrine to a lost life she never got to live. “This time it will work,” she thought. But it never did. And it never could.

In the west, Godzilla is often looked at as an analogy of all of the anger and hurt that the Japanese people suffered as a result of the bombings.

But, if Godzilla (the creature) is a metaphor for rage, why is that rage directed at Japanese citizens and not the people of the United States? Could it be because the Japanese were the first to bomb a US ship? Maybe they felt responsible, and Godzilla is instead a manifestation of that guilt.

Surely, that reading isn’t incorrect. In my mind, Godzilla does not represent the guilt of the unaffected, but rather the vengeance of those Hibakusha that people couldn’t even stomach looking at.

Godzilla would be released a mere two months after the incident in Bikini Atoll. Viewers were skeptical. They hadn’t seen anything quite like Godzilla before; none of us had. “Creatures like this don’t exist.” “Why would a lizard breathe fire?”

There were countless cries against the film, stating that it was exploiting Japan’s tragic history.

But as hard as some worked to dissuade people from seeing the film, audiences flocked to the film in droves.

Director Ishirō Honda stated the movie certainly wasn’t glorifying the bombing, but it was intended to help Japan come to terms with it and the lingering effects.

No matter what people thought of the film’s intent, they couldn’t get enough of it. Godzilla was the eighth highest grossing movie of the year. The titular creature has become a mainstay in pop culture and spawned an enduring cinematic legacy.

Godzilla would be released in the states in 1957. But it wasn’t Honda’s version. Things had been taken out, switched around, and even re-filmed. The lofty message of suffering and healing was watered down. Eventually, Godzilla became more of a child’s toy than a representation of the horrors of war.

Throughout all of Godzilla’s big screen evolution over the years, what the iconic creature represents is rarely discussed.

You were probably made to look at pictures of the victims of Hiroshima in history class so you could grasp the torment civilians were burdened with during the horrific bombings. But you probably weren’t told about how many victims were cast aside afterward if their injuries weren’t severe enough to need more medical care — or how the people who bore radiation scars and permanent disorders lurking beneath the skin were treated like ghosts. Invisible.

While the Japanese government still doesn’t acknowledge this suffering, doesn’t showcase these people, one of their biggest cultural icons has become a beacon for the wounded.

After all, Godzilla itself is a Hibakusha.

Twisted, scarred, and left a monster from something completely and totally outside of its control, Godzilla is a hero of the outcast. Channeling the pain and rage of being abandoned, Godzilla is not the hero of the first film, no matter how watered down it became in recent visions. But it isn’t the villain either. Instead, Godzilla is the representation of righteous vengeance.

If GODZILLA is a representation of the pain of the war and the refusal of the people to care about the scarred, SHIN GODZILLA is what happens when the leaders of the government can’t be bothered to care for literally anyone but themselves.

Directed by Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi, the latest Godzilla movie from Japan follows the missteps of the upper class. A not fully formed Godzilla emerges from the waters and terrorizes parts of Japan. The general population and the government officials are both in a state of pure shock. Officials find scientists and try to organize the military to stop him before he can attack again, but they find themselves more preoccupied with keeping him away from American forces and see him as a tool. They refuse to evacuate cities multiple times, resulting in mass casualties and destruction.

Shin Godzilla is possibly the most relatable film to the American public right now, despite its origins.

Shin is an unstoppable force that no one saw coming; much like the virus that has ravaged the nation. While some death, and a lot of destruction, is unavoidable here, the government misses countless opportunities to save its people, too focused on money and power. Whereas people could have been easily warned and relocated, they are instead left to be trampled over by something they can’t fight back against.

Even in their last moments, when they could possibly make a change, high officials make the decision to try to run instead. They are blipped out by Shin almost immediately; their lives meaning nothing more to him than anyone else’s, despite their wealth and power.

Eventually, Shin is frozen, his path of destruction ceased. But the ripples of his presence have forever changed the citizens of Japan. Confronted with their own mortality, and betrayed by a power that could have helped them, they will be the ones to rebuild the nation. They will be the ones left to scramble for money to try to rebuild their lives, and they will be left to deal with the trauma of living through the rampage, and dealing with the loss of their loved ones. Their way of life will eventually fade back to what it once was, just with a new level of paranoia and pain.

Follow Us!