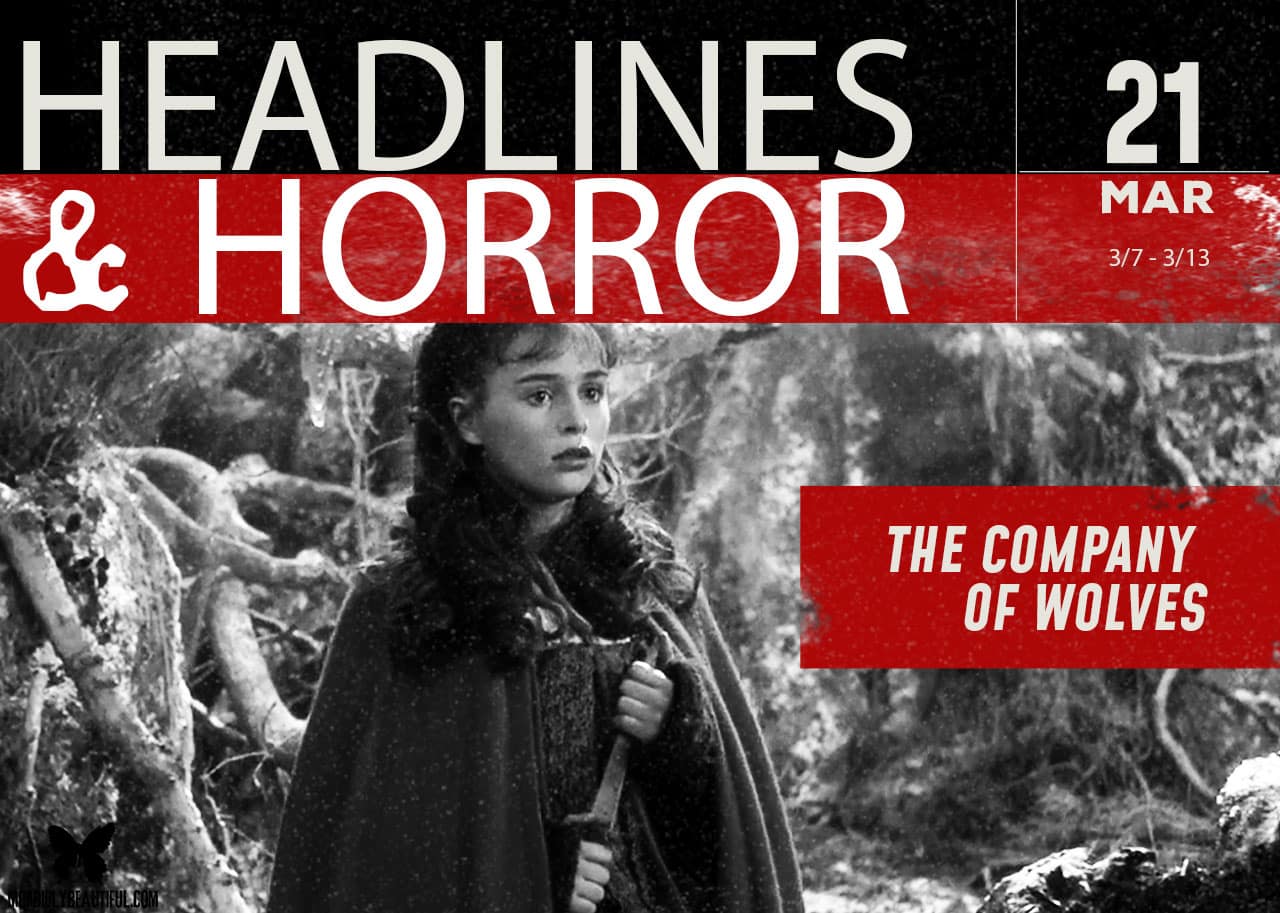

While women’s issues take center stage in front of a critical audience, the movie of the week (Mar. 7-13, 2021) is “The Company of Wolves”.

Enter Neil Jordan’s 1984 film The Company of Wolves, a dark retelling of a classic fairytale from a strong feminist perspective.

The late feminist novelist Angela Carter was known for subverting classic fairytales, infusing them with sexual references and suggestive metaphors. Irish director and novelist Neil Jordan first met Carter at a writer’s conference, and it was Carter who expressed an interest in bringing her short stories to the screen. The short story called “The Company of Wolves “(from the collection The Bloody Chamber), which forms the basis for the film, was only 12 pages long. So, Carter and Jordan collaborated on a script that built the story up in layers, inserting imagery from classical fairytales into a dream-like, episodic format.

There’s very little narrative to speak of — only a series of cautionary fables told by a genial grandmother (played by the remarkable Angela Lansbury) to her beloved granddaughter Rosaleen (Sarah Patterson). The entirety of the film seems to exist within Rosaleen’s imagination, reflecting her sexual awakening and her reckoning with the notion that men are, quite literally, beasts.

Jordan says he always understood the film as a meditation on the ways society teaches young women to look at themselves sexually and to recognize the things to be afraid of.

THE RIGHT FILM FOR THE RIGHT TIME

Thanks to the efforts of Walt Disney, most of us equate fairytales with heroism and happy endings.

But long before Disney’s family-friendly sanitization of these stories, the Brothers Grimm gave us dark and violent cautionary tales about the dangers that lurk around every corner — and within the heart of every man. In 1984’s beautifully allegorical film The Company of Wolves, Carter and Jordan planned a modern retelling of Charles Perrault’s tale of temptation and deception, Little Red Riding Hood. The result was a Freudian horror fable about burgeoning female sexuality, male desire, and gender roles.

It also happens to be one of the more criminally underrated horror films in history.

The film opens a red lipstick-wearing teen girl, locked in her bedroom and surrounded by dolls and other remnants of her rapidly fading youth, as she slips into a restless sleep full of nightmarish and fantastical dreams. The audience is invited to enter the haunted forest of her subconscious, full of menacing, human-sized toys and, of course, bloodthirsty wolves. As she falls deeper into slumber, the scenery morphs from the woods of a sadistic storybook to an authentic 18th-century village. Our heroine, Rosaleen, is a farmer’s daughter, living with her loving parents but spending ample time with her somewhat perverse grandmother.

Rosaleen can’t get enough of her grandmother’s sadistic, supernatural tales of werewolves and wicked men.

Meanwhile, a wolf has been terrorizing the village, causing panic and paranoia. In the midst of this fear, the surprisingly fearless Rosaleen dons a bright red shawl knitted by her grandmother, packs a picnic basket, and journeys into the forest to pay Granny a visit. Given the literary inspiration for the tale, we have a pretty good idea of where things are headed.

The production design is sublime, led by the late Anton Furst (who later worked on Tim Burton’s Batman), and impressive despite the film’s shoestring budget. And, while the film is more akin to dark fairytale than visceral horror, the werewolf sequences do not disappoint. They are both highly original and gruesome. Makeup specialist Christopher Tucker (who designed John Hurt’s makeup in David Lynch’s masterful The Elephant Man) delights with wolves literally climbing out from the insides of men, faces splitting open, and skin being ripped off. Though by current standards, the practical effects do show their age, they are spectacular for their time; wonderfully hideous and bloody.

However, unlike much of the film’s 80’s horror contemporaries, the gore isn’t the central focus in The Company of Wolves.

First and foremost, this is a feminist parable about the dangers associated with a young woman’s sexual awakening. As we follow Rosaleen’s metaphorical loss of innocence, symbolized by the color red — lipstick, a cloak, blood on a wolf’s jaws — we see a young woman who refuses to walk the beaten path, embracing rather than fearing her femininity and sexuality.

During one of her grandmother’s tales, she asks, of the story’s woe begotten heroine, “Why couldn’t she save herself?” It’s a question that is quickly dismissed. But Rosaleen continues to subvert expectations and gender norms, choosing instead to become her own hero rather than waiting for a man to save her from the danger of other men. When she enters the forest for the Little Red Riding Hood-inspired climax of the film, a suitor offers to walk with her and keep her safe.

She simply smiles, brandishes a knife far bigger than his, and says, “No, I’ve got this to protect me.”

WHY IT MATTERS

The stories told to Rosaleen by her grandmother are meant to prepare the young girl for the dangers that accompany her blossoming sexuality. They focus on the perils that await women who fall for the wrong men — and the duplicitous nature of attractive and silver-tongued men who hide darkness within (“the worst wolves are hairy on the inside”).

The morals of these fables strike a familiar tone: stay on the path and don’t trust handsome strangers. Granny warns that “men often grow into wolves as they grow older” when the lines between beastly desires and treacherous pride are blurred.

One story follows a young woman who marries a handsome traveling salesman, only to lose him to the call of the wolves. Years later, after she remarries and starts a family, her presumed-dead husband returns to demand his supper as if no time has passed at all. Angry that she has not remained chaste in his absence, he transforms into a wolf and attempts to kill her. When her new husband arrives home, he kills the man-beast, then violently hits his wife. Although a man in this story is entirely to blame — for abandoning his wife and returning to wreak havoc on her new family — the woman bears the shame and scorn from both her former and current husband.

At one point — symbolically marking the transition of Rosaleen from girlhood to womanhood — she begins to tell her own stories, beginning with a fairytale she tells her mother about a vain nobleman who gets turned into a literal animal by the village woman and witch he cruelly scorned.

Once Rosaleen becomes the storyteller, we begin hearing about women who take control of the narrative, choosing vengeance over victimization.

In one of the most powerful lines of the film, she tells her mother that her heroine’s pleasure “would come from knowing the power she had”.

Eventually, Rosaleen takes center stage in her own dreamscape, enacting Little Red Riding Hood with a handsome stranger who plays the role of both huntsman and wolf. Once she arrives at her granny’s house, she knows exactly who — and what — is waiting for her. But, even though she quickly realizes the danger she is in, she refuses to give in to fear. When the werewolf asks if she’s afraid, she boldly retorts, “it wouldn’t do me much good to be afraid, would it?”

Instead, she uses her feminine appeal and cunning to disarm and then disable the predatory male.

Once the tables have turned, Rosaleen tells her final tale, that of a she-wolf who ventures into a village and is shot and wounded by the people who fear her. It’s a story of a woman attempting to return to her childhood but quickly finding that impossible. Once a woman has embraced her sexuality (symbolized by her transformation into a wolf), there’s no turning back. She is no longer innocent in the eyes of society.

Like the pure white rose that turns a blood-soaked shade of vibrant red, she is forever tainted.

Her femininity is a thing to be both desired and feared.

A woman choosing her sexuality in a patriarchal society— choosing to desire and be desired — makes her more predator than prey. And that is the greatest horror in Rosaleen’s world, and in the real world: she is well aware of the dangers of her sexuality, but she embraces it nonetheless; becoming the wolf.

The final scene is masterful, depicting the final end of innocence as fantasy comes crashing into reality and Rosaleen’s childlike sanctuary is shattered. Though confident and brave in her dream, she’s beset by terror in the real world. If the wolves symbolize sexuality, it’s a reminder that the fantasy of becoming a sexual being may be seductive, but the reality is often wrought with unspeakable horror and fear.

The film ends with a haunting narration over the credits:

“Little girls, this seems to say, never stop upon your way. Never trust a stranger or a friend. No one knows how it will end. As you’re pretty, so be wise. Wolves may lurk in every guise. Now, as then, ‘tis simple truth. The sweetest tongue has the sharpest tooth.”

WATCH IT NOW

Monday, March 8th, was International Women’s Day, a global holiday celebrating the cultural, political, and socioeconomic achievements of women. It is also a focal point in the women’s rights movement, bringing attention to issues such as gender equality, reproductive rights, and violence against women. While it’s tempting to see the #MeToo movement as a new era for female empowerment, as Gretchen Carlson points out in her editorial addressing the fallout from the Meghan and Harry interview, it’s clear we are a long way from changing deeply embedded cultural stereotypes.

In the four decades since The Company of Wolves was released, many modern horror films have attempted to subvert the “Final Girl” trope and address the genre’s long and sordid relationship with sexism. But we remain a culture obsessed with glorifying and dismissing onscreen and offscreen violence against women.

The crux of the film isn’t that women should do what is necessary to protect themselves against the threat of violence from men. Rather, it’s that women can always face sexual violence from both strangers and friends — no matter what they do to prepare.

The Company of Wolves is as impactful and relevant in 2021 as it was in 1984 for one simple but truly terrifying reason: the world — like the fabled woods of our storybooks — still isn’t safe for women.

Follow Us!