On the anniversary of its release nearly a century ago, we celebrate the enduring legacy of a classic, the immortal “The Mummy”.

Universal introduced movie-goers to the iconic Count Dracula and the Frankenstein monster in 1931, choosing The Mummy for the next installment in its monster film catalog in 1932.

This choice no doubt had to do with the public’s current obsession with ancient Egypt, sparked by the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. However, The Mummy stands apart from Universal’s pantheon storywise.

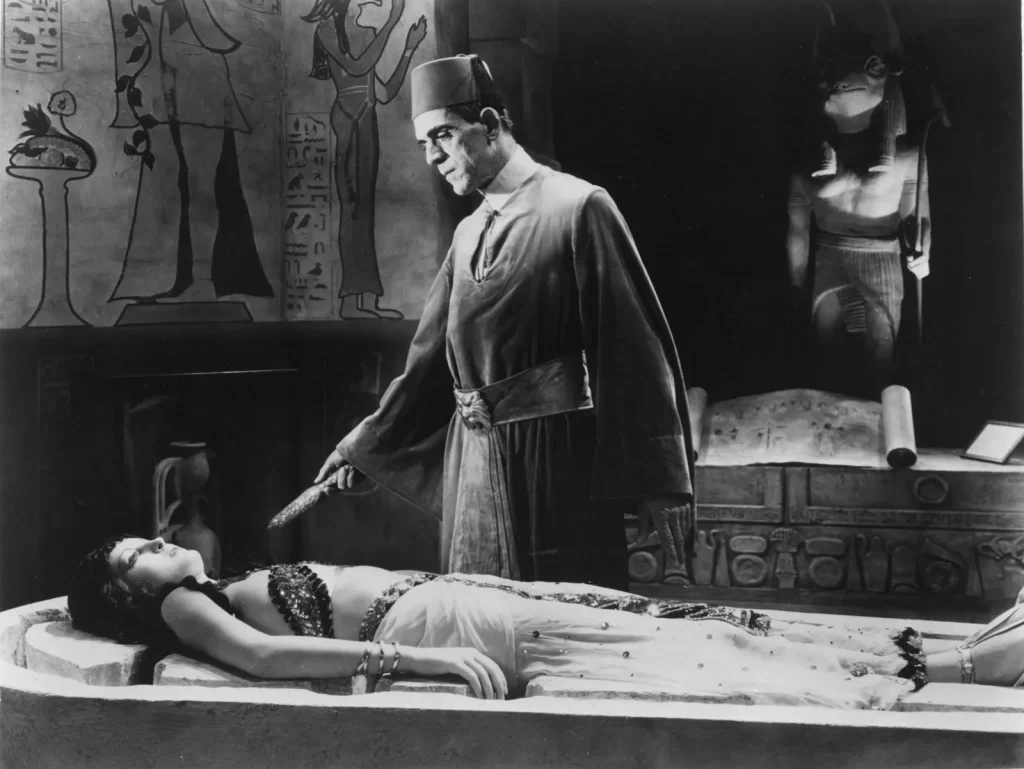

While the film’s predecessors, Dracula and Frankenstein, center around a monster hunt, The Mummy (aka Imhotep aka Ardeth Bey), played by Boris Karloff, is fleshed out in three dimensions with a backstory. He’s presented as more human than a monster.

The Mummy is a horror romance. Imhotep wants to be reunited with his lost love.

Plot aside, the film has a shadowy, dreamlike atmosphere, the magic and mystery of Ancient Egypt, and another iconic performance from Karloff.

Released on December 22, 1932, The Mummy was directed by Dracula cinematographer Karl Freund. Nina Wilcox Putnam and Richard Schayer wrote the story.

Horror icon Boris Karloff delivers yet another memorable performance as the titular character.

The cast features two actors who appeared in 1931’s Dracula, Edward Van Sloan as Dr. Muller and David Manners as Frank Whemple.

The film opens in 1921 with Sir Joseph Whemple (Arthur Byron) and his friend, Dr. Muller, inspecting Imhotep’s mummy found during Whemple’s recent expedition. Muller concludes Imhotep was buried alive, noting that the high priest was buried with his viscera and that there are signs of a struggle.

Imhotep’s tomb also contains a casket that has a curse on it.

Ignoring Dr. Muller’s warning, Sir Joseph’s assistant, Ralph Norton (Bramwell Fletcher), opens it and finds the Scroll of Thoth. Norton translates the scroll and reads aloud, bringing Imhotep back to life. Norton begins laughing hysterically as Imhotep escapes with the scroll. Eventually, Norton loses his mind.

Fast forward ten years later.

Imhotep manages to assimilate into society and assumes the identity of Egyptian historian Ardeth Bey. He contacts Sir Joseph’s son, Frank (Manners), and Professor Pearson (Leonard Mudie) with the location of Princess Aknh-esen-amun’s tomb. The archeologists unearth many artifacts which they bring to the Cairo Museum.

We discover that Muller was right — Imhotep was buried alive as punishment for sacrilege.

Imhotep and Princess Aknh-esen-amun had a forbidden relationship. When she dies, Imhotep is caught trying to resurrect her and buried alive as punishment. Bey meets Helen Grosvenor (Zita Johann), who resembles the princess and falls instantly in love.

Bey believes that Grosvenor is the princess reincarnated. Meanwhile, Frank Whemple also falls in love with Helen.

Conflict ensues with Bey intent on making Grosvenor his immortal bride and Muller and Frank trying to stop him.

Edward Van Sloan and David Manners are up against Karloff’s Imhotep.

In Dracula, Van Sloan played Dracula’s nemesis, Van Helsing, and Manners played Jonathan Harker. Like Van Helsing, Muller is an occult expert, paranormal detective, and mentor to Manners’ Frank Whemple. Like Dracula’s Jonathan Harker, Frank’s love interest, Helen, is stalked by a supernatural being. However, unlike Dracula, Imhotep’s motivation is to be reunited with his lost love.

If you recall, the lost reincarnated love subplot to Dracula wasn’t in the 1931 film or any of the subsequent Hammer films. We wouldn’t see Dracula in love until 1979’s Dracula with Frank Langella and Kate Mulgrew. In Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 reimagining of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mina is the reincarnation of Dracula’s wife, Elizabeta.

Romance aside, Helen experiences hypnotic trancelike states like those experienced by the female victims in most vampire movies from classic to contemporary. It’s during her trance that her past life as an ancient Egyptian princess is revealed.

The film’s atmosphere, like its predecessor, Dracula, is shadowy, dreamlike, and reminiscent of silent films.

The sequence where Helen’s past life is revealed to her has an ethereal quality to it as well as the smoky atmosphere as Imhotep tries to cast the spell to resurrect his lost love.

The costumes and makeup in flashbacks to ancient Egypt add to the magic of the film.

As Imhotep, Karloff effectively gives off an aura of magic and mystery. The makeup has a texture that makes Imhotep stand out in close-ups from a regular human, but that’s about it. Karloff doesn’t stumble around covered in wrappings throughout the film, and only appears as a bandage-wrapped mummy in the beginning.

It’s Karloff’s performance that gives off chills and otherworldly vibes — his voice and mannerisms. Karloff speaks in a monotone, and his movements are slow and languid.

The Mummy, like many films, bears the stamp of its time period.

Most of Universal’s monster films were made during the Great Depression. Horror during this period had otherworldly and supernatural themes. Extreme glamour, ghost stories, and the paranormal could serve as an escape during a difficult time period.

During this period, the American public was also obsessed with ancient Egypt, called Tutmania or Egyptomania.

The Mummy was inspired by the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 by archeologist Howard Carter and funded by the Earl of Carnarvon.

Fashion was impacted by archeological finds, with beaded gowns inspired by sheath dresses from ancient Egypt. There were also ancient Egyptian motifs, including lotus flowers, scarabs, and snakes, incorporated into jewelry at the time. Art Deco used sharp angles and color schemes similar to ancient Egyptian artwork. Egyptian imagery even made its way into advertising.

While American pop culture was obsessed with mummies at the time, the film’s story may have originated in Italy.

Looper cites David Robson as stating in his book, The Mummy, that screenwriters Richard Schayer and Nina Wilcox Putnam based the film’s story on a story about an 18th-century Italian who claimed he was an alchemist and went on to become a well-known mystic in the community. The story evolved to center on the character Imhotep.

All of this leads me to wonder what inspired the lore behind cursed tombs and mummies that rise from the dead.

Grunge reports that curses on tombs did exist as a measure of protection from grave robbers. Not only pharaohs but common people had curses inscribed in their tombs. Grunge points out that since royal tombs were more secure, curses were more often found in the tombs of commoners. However, there aren’t many reported accounts of grave robbers suffering the effects of these curses.

There’s one story dating back to 1699 of a Polish traveler who stole two mummies from tombs in Alexandria. The grave robber reported being visited and menaced in his dreams by two entities. A severe storm also kicked up, and as the storm worsened, he threw both mummies overboard. After he did this, the storm reportedly abated.

All sources agree that the idea of The Curse of the Pharaohs entered the mainstream with the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in November of 1922.

Even though there weren’t any curses inscribed in King Tutankhamun’s tomb, tales of the curse spread after Carter’s financier, Earl of Carnarvon, died shortly after the tomb’s discovery.

Carnarvon died of blood poisoning after he cut himself shaving and became infected.

Carnarvon wasn’t the only person tied to the tomb’s discovery who suffered an untimely death. There’s a list of people connected to the tomb itself or connected to someone involved in the tomb’s discovery and how they all met their demise. Howard Carter died of lymphoma ten years after the discovery.

Grunge cites a study in 2022 conducted by the British Medical Journal that found that most of the victims of the alleged curse were Westerners and not native Egyptians. Not surprisingly, no correlation was found between the deaths and exposure to the tomb. Those who entered the tomb weren’t more likely to die within ten years than those who didn’t.

Another theory is that these tombs may have had harmful spores and mold, and those who were part of the expedition were likely already ill. The rest were just people looking for tenuous connections to confirm something they already believed in.

Did the ancient Egyptians believe a mummy could rise from their tombs through magic?

Looper cites Professor Stuart Tyson Smith’s article “Unwrapping the Mummy: Hollywood Fantasies, Egyptian Realities” in the book Box Office Archeology: Refining Hollywood’s Portrayals of the Past. Smith writes that the idea of a mummy coming to life wasn’t entirely unknown in Ancient Egypt. He references a papyrus acquired for the Boulaq Museum (now the Egyptian Museum in Cairo) in 1865, containing ‘The Story of Setna Khaemwas and the Mummies.’

Smith writes that the story told on papyrus has much in common with the plot of The Mummy.

After Setna tries to steal the cursed Book of Thoth from the tomb of Naneferkaptah, he is confronted by the mummy of Naneferkaptah and the spirits of his wife and child. They tell Setna a cautionary tale about the consequences they suffered in possessing the scroll placed in their tomb to keep it from mortal hands.

Setna ignores their tale. When he realizes the mistake he’s made, Setna tries returning the scroll and also agrees to return Naneferkaptah’s mummy with the remains of his family.

“In a moment ‘strikingly similar to the scene with Karloff’s mummy,’ Smith writes, “Naneferkaptah appears as an old man and leads Setna to the tomb of his loved ones.”

However, The Mummy’s influence echoes throughout horror history and not only in film.

The Mummy is a figure that has come and gone over the years in the horror genre.

As with Dracula, Hammer Studios produced a series of mummy-themed movies from the late 1950s, 60s, and 70s. The Mummy was revived with 1999’s big-budget, The Mummy and its sequel, The Mummy Returns (2001), starring Brendan Fraser. A reboot starring Tom Cruise hit theaters in 2017. We also can’t forget Don Coscarelli’s cult-classic 2002 horror comedy, Bubba Ho-Tep.

In literature, one of the first mummy-themed stories, Jewel of the Seven Stars, was written by Dracula author Bram Stoker.

Vampire Chronicles author Anne Rice incorporated the culture of Ancient Egypt into her vampire stories and wrote The Mummy or Ramses the Damned, which has two sequels co-written with her son, Christopher Rice, Ramses the Damned: The Passion of Cleopatra and Ramses the Damned: The Reign of Osiris.

An interesting, fun fact is that according to Anne Rice.com, The Mummy or Ramses the Damned was originally written as a script for a film. Rice didn’t care for the changes they wanted her to make, so she turned her script into a novel.

The Mummy has made an indelible mark on horror history and will continue to do so. As ancient cultures continue to fascinate, mummies will continue to be revived from their tombs, in various creative incarnations, for many years to come.

Follow Us!