An under-appreciated genre masterpiece, “The Changeling” is a tale of a man haunted by the ghosts that live in his house — and his head.

The Changeling doesn’t mess around.

In the first three minutes, George C. Scott warmly banters with his family and then watches them get crushed by a runaway salt truck. He sees it all through the side of a phone booth, stuck inside. Too overwhelmed, too desperate to do anything with his hands but pound at the glass. Too mad to do anything but wail. The world freezes as he does, impossible past catching up to unthinkable present, and the rose-red title card fades in over silence.

That phone booth is the first of many glass coffins in The Changeling, each filled with another corpse that won’t admit they’re dead. They plunk at their pianos and pound their rotting fists on antique desks and hope to God or whatever’s waiting that nobody notices they’ve got no fire left in their eyes.

Scott’s dead man walking, composer John Russell, moves clean across the country after his family’s tragic deaths, hoping anybody who looks him in the eye in Seattle won’t remember what was behind them in New York City.

Like most drastic external solutions to internal problems, it works. For a while.

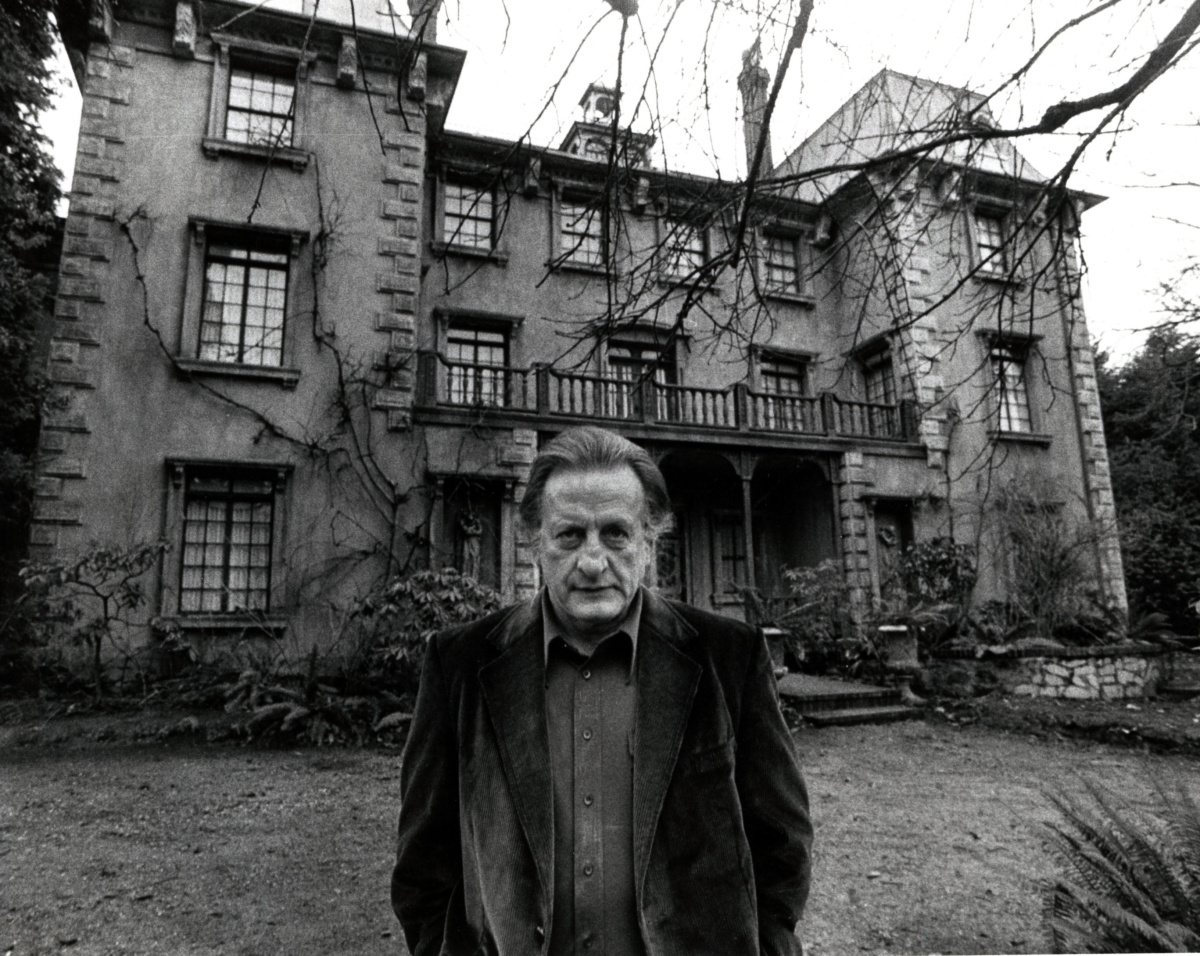

Russell rents the kind of mansion they stopped building when the Sherman Act outlawed oil monopolies. Each floor has too many doors to count and more windows than out-facing walls. I can’t be sure they pulled a Kubrick and built the set with impossible geography, but like the Overlook, the Carmichael Mansion was elaborately constructed on a soundstage. The Victorian sprawl is unsettling instead of grand. Old money clings to its three stories like black mold. Every wide open parlor is another barren horizon over Russell’s shoulder, begging for signs of life, occupied by something worse.

Not that he notices right away.

Russell is too busy going through the motions. Preparing lectures for his eager students. Getting buzzed enough to charm at collegiate functions. Sitting at his piano and waiting for his fingers to do something interesting. Crying himself awake at six in the morning, until the bellowing noise in the basement gets him out of bed.

The tricks in The Changeling are as old as the ghost story itself.

Strange noises. Doors squealing open of their own volition. Sudden movement from something that cannot or, at the very least, should not move.

That primeval authenticity comes courtesy of a real ghost story. Playwright Russell Hunter moved from New York City to a mansion in Denver for the too-good-to-be-true rate of $200 a month. Then came the pounding behind the walls and faucets turning themselves on and off and the child’s room hidden behind a closet. I won’t divulge too much more about Hunter’s story because he used just about every beat of it in The Changeling, for which he earned a story credit.

There are gaps to his account. Like the rent, it’s both too good to pass up and too convenient to believe.

Believers and non-believers can carry out any chicken-egg arguments in the comments — are ghost stories scary because they sound like alleged accounts of real hauntings or are alleged accounts of real hauntings scary because they sound like ghost stories — but the fact is, The Changeling feels like it was based on a true story, despite never stooping so low as to admit it.

There’s no Rubik’s Cube collapse like the end of Poltergeist, no skeletons on strings.

You won’t see much in The Changeling, but you see George C. Scott see it, and that’s even better.

It’s rare to see an actor of such stature tackle a horror project, especially in 1980. Even the following year’s Ghost Story had best-selling source material to woo its cast. Here, Scott is on his own against wind machines and noises added in post, and he sells every second of it. There’s no better example of his commitment than that damn bouncing ball.

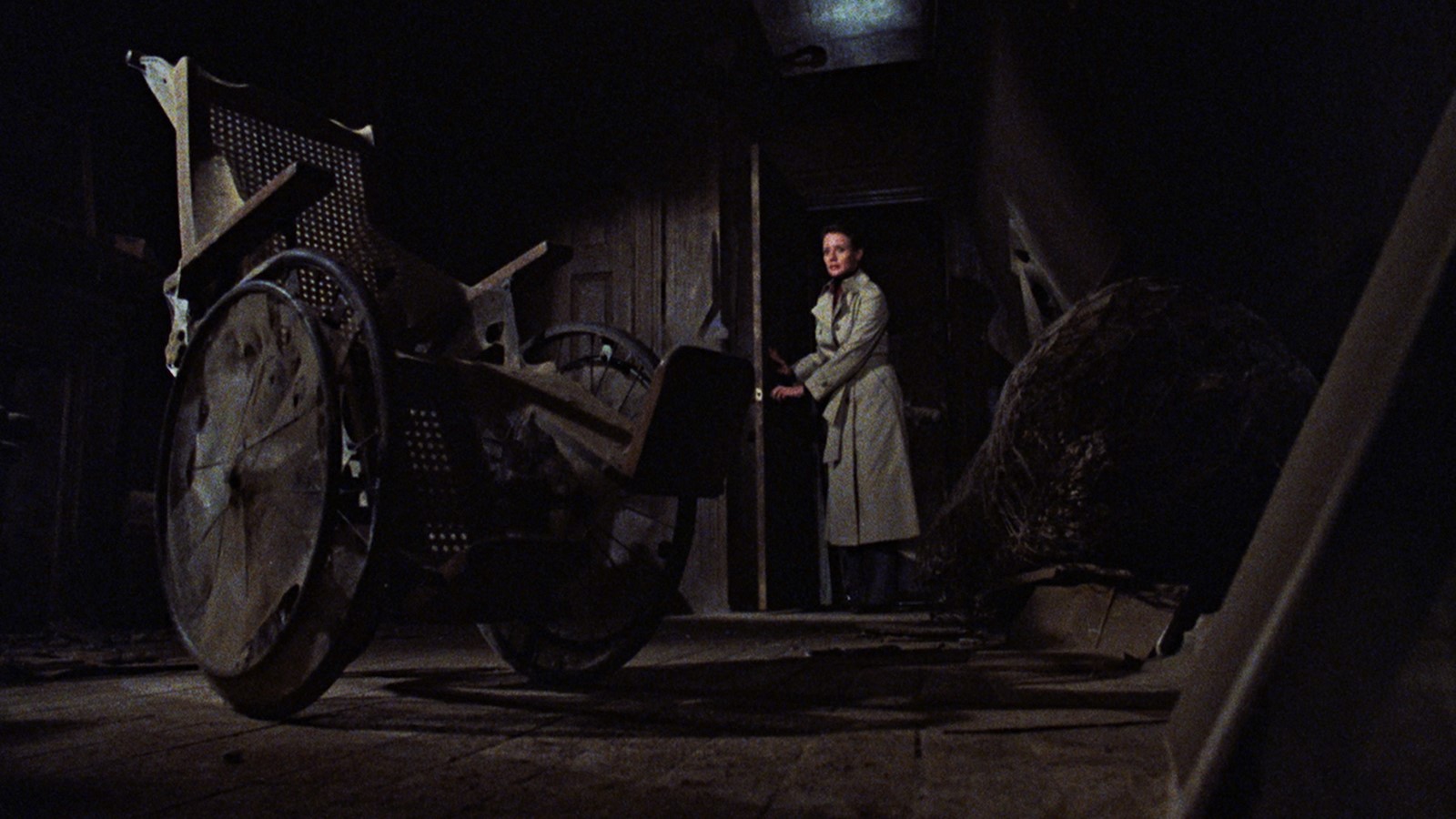

Russell’s only souvenir of his dead daughter is a red rubber ball. He keeps it, but not too close, hidden away in a roll top desk. He almost forgets about it until kindly local Claire, played by Scott’s real-life wife Trish Van Devere, finds it and asks where it came from. Russell almost forgets about it again until it comes bouncing down the stairs of the mansion and there’s nobody else home.

It’s been parodied to within an inch of its life, but you can’t beat the original. It’s just a ball. It’s just bouncing. Like that joke about a clown at your door around noon being odd and a clown at your door around midnight being terrifying, it’s the context that gets you.

Scott doesn’t overplay it, doesn’t shriek or run. He doesn’t need to scare us — the dull thumps down the steps already took care of that. His response, even though there could be something waiting around the corner at the top of the stairs, is to pick it up, drive across town, and throw the ball into a river. When he comes home and the ball bounces down the stairs again, harder this time, John Russell immediately consults the nearest department of psychic research.

The Changeling is a masterclass in the subtle difference between scaring the audience and telling the audience it should be scared.

When Russell finds his medium, she doesn’t bring candelabras and there is no mood lighting beyond the natural dark. For an entire scene, she is the special effect. Olivier-winning actress Helen Burns spent most of her career, on and off Broadway, in comedy. But with nothing more than a pencil, paper, and her unwavering voice, she gives the house its horrible pulse.

Much ink has been spilled in the name of Halloween’s POV camerawork and the nauseous tension of seeing the victim through the killer’s eyes.

The Changeling does it one better, cutting between Russell and company waiting for a sign and something working its way through the mansion to provide one. Not fast, methodical, taking the stairs slow, almost unsure. We know it’s coming. We know what it sees. But we don’t know what it even looks like.

The price of admission, though, is tragedy.

The Changeling starts sad and rolls downhill from there.

Russell buries his grief in the hunt, poring over 80-year-old newspaper clippings and tearing up floorboards just for some concrete answers about his haunted rental. His unfinished business and the unfinished business of whatever’s living there with him become one and the same. Toward the end, when he comes home to every door in the house slamming at the same time, he doesn’t scream, at least not in terror.

“You goddamn son-of-a-bitch,” he seethes, “What do you want from me?” The shout that lingers longest after comes last: “There’s nothing more to do.” Russell is done pounding against his glass coffin. He realized it had a door and he could open it if he stopped trying so hard to prove everything was okay. Now he’s just tired of the noise.

The Changeling edged out The Shining on Martin Scorsese’s personal ranking of the scariest films ever made. That’s a potent endorsement for such an understated bump-in-the-night movie. Appropriate enough, given director Peter Medak’s understated pride in his work: ”It’s very nice that it’s noted as one of the great ghost stories.”

The Changeling is a great story about ghosts, both living and dead.

Follow Us!