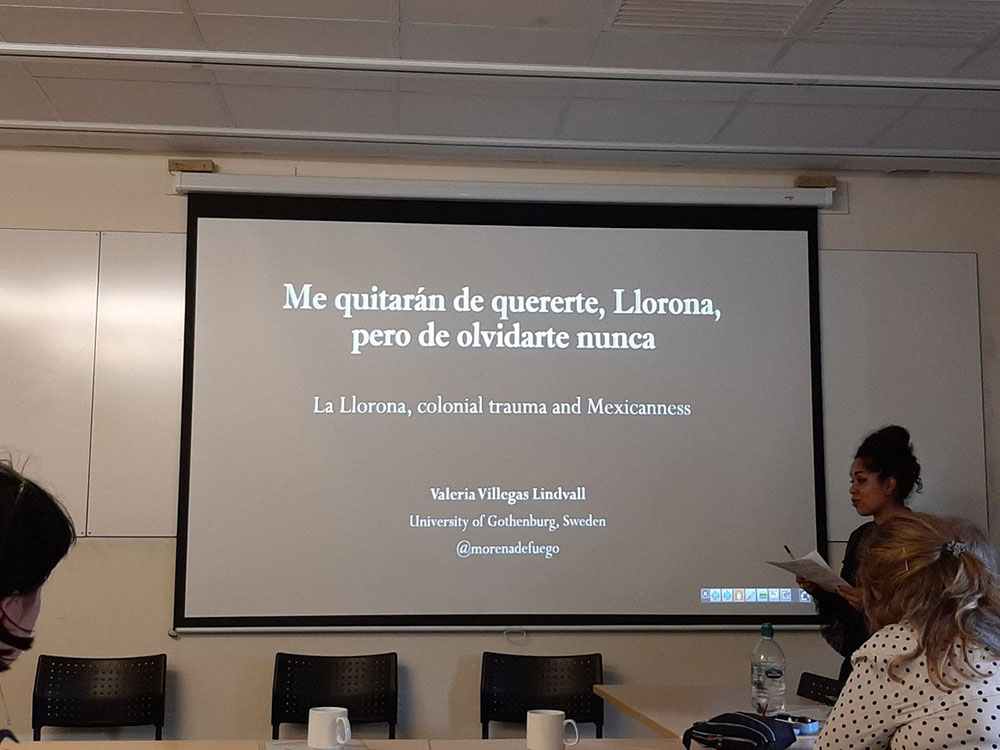

We talk with genre scholar Valeria Villegas Lindvall about the feminine relationship to horror and the power of the genre to challenge power structures.

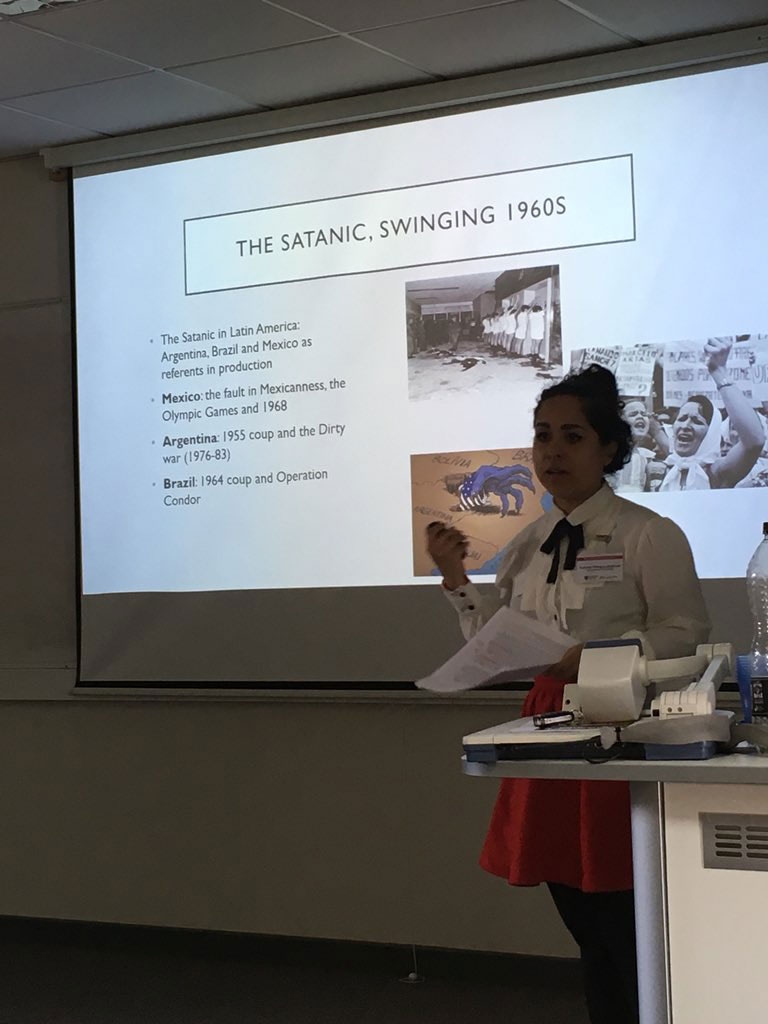

We here at Morbidly Beautiful were lucky enough to cover this year’s Final Girls Berlin Film Festival. In addition to screening the amazing films featured at the fest, we were also able to sit down with some of the brilliant and inspiring presenters, including Valeria Villegas Lindvall. Valeria is a true scholar of the genre, currently pursuing her doctorate in film studies at Gothenburg University with a focus on Latin American horror.

She has held a variety of positions in the writing business, but her heart truly lies in a metaphoric bed of blood and guts (and don’t forget glamour —among her work is a piece concerning the healing power of camp by way of the Boulet Brothers’ spectacular drag competition show Dragula).

In advance of her panel discussing “The Bad Mother in Mexican Horror,” I had a chance to ask her some questions about her thoughts on the genre, the trajectory of feminine horror, and the importance of understanding the roots of our fears.

INTERVIEW WITH VALERIA VILLEGAS LINDVALL

1. What do you believe is the enduring appeal of horror to female audiences?

I believe that a big part of the appeal that horror film seems to have with womxn has a great deal to do with the transgressive nature of the genre. It allows us to project what is possible and reimagine orders that transcend the binds of gender and sexuality. Certainly, unequal distributions of power are liable to transformation and critique in cinema at large, but horror taps into the deepest and most unexplored anxieties of the audiences.

I think that horror affords – let’s also remember that it is often adjacent to fantasy – an incredible potential for subversion and negotiation, it presents a blank slate upon which to indict unexamined oppressions and imagine more nuanced versions of ourselves and our relation to the world.

2. What do you think separates cathartic horror from pure shock? Is there any value in pure shock?

I’m not sure one can do without the other… on one hand, I believe there’s a meditative, contemplative and reflective quality in horror, for sure. On the other, for there to be pure shock, or anything like it, one would be required to think about the normative categories that this shock disrupts, and that’s essential.

It is the nature of shock as a catalyzer for critical engagement what I find tremendously fascinating, as it forces us to turn upon the structures that are shifted, questioned or indicted. There is something alluring in this danger and the permeability of the limits that shock evinces… it forces us to question: what is at stake? The gesture of shock is productive because it affords that radical disruption, to throw into chaos, to confuse. It’s pure punk.

3. I really enjoyed your piece on The Book of Birdie and the complex symbolism of menstruation, especially within a religious context. (REALLY need to see that movie now!) What do you think of the idea that our interest in horror and the supernatural stems from some insecurity in our own faith (whether we’re believers or not)?

I’m thrilled that you enjoyed that piece! It is really close to my heart, and I’m very grateful that its final version reflects many of the insightful conversations and feedback from feminist colleagues, whose kindness made the text grow and flow (pun totally intended). It’s also especially dear to me because of the very special enterprise that Elizabeth E. Schuch, the creator, writer and director of the feature, takes to task.

I see in this film as a tremendously generous exercise in transgressive female writing from and about the body. Its perspective of lavish abandon depicts a matter that has been taboo in religious contexts for a while. It presents, in my perspective, a reimagining of menstruation and female sexuality from a point of view of female writing. I’m very interested in the idea of religious horror and the notion of spirituality and fear as experiences that can come together, so The Book of Birdie provides a fantastic point of departure for this reflection.

I believe that more than insecurity of faith, the divorce between body and soul – which has been a matter of philosophical controversy for a very long time – plays an important role in this fear of the divine as something that has to be coercive and exterior. This is precisely why Birdie provides a scope that I felt was missing in the equation: the possibility of redefining the relation between the body and the divine becomes less frightening and more productive and intimate.

The way in which this is reframed not as a punitive relation with the divine, but as an embodiment of the divine in the female body complicates the submission to faith, and somehow reaffirms that this sense of spirituality and organic belonging to something greater doesn’t need to be policed or instigate doubt, but can rather present radical certainty.

4. What distinguishes the Latin American female monster?

I was thinking of this question for a while, because it encapsulates a major concern in my research. At large (it’s a much longer conversation), and following several decolonial thinkers – as I quoted elsewhere – the notion of Latin America is in permanent quotations for me. The matter of gender is inseparable from the matter of Latin America as a geopolitical entity coined in exteriority, and in this context, I believe they’re open for critique as arbitrary categories that cannot be seen as detached from historical processes triggered by colonial intervention.

I refer to the Latin American female monster because this characterization allows me to encapsulate several angles that require addressing from a critical perspective – the notion of gender and national identities as projects steeped in unequal distributions of power, and the exclusion of racialized bodies from the quality of humanity itself – thus justifying their ‘otherization’ and exploitation.

The recuperation of the monster in this particular set of circumstances then becomes a potentially radical gesture, articulating the intersections of race, gender, class, ability and other factors through the lens of horror and its incredible affordances – it is a way to confront identities forged in colonial trauma, making sense of the languages that have for long made out of racialized, non-male bodies, monstrous entities in the eyes of those that seek their obliteration, dehumanization and exploitation.

5. There are several legends across cultures of the scorned woman who murders her children, but La Llorona stands on her own as an enduring figure in popular culture. Why do you think her story in particular still resonates?

The figure of La Llorona is a paramount trait of Latin American folklore. I love Milagros Palma’s quote that describes her wail as a resonance from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego in Argentina: her presence keeps coming up as the (dis)embodiment of colonial trauma in Latin America at large, the pain of the racialized body made an eternal spectacle.

Her validity, I argue, is continuous in her capability to evince her loss, her forced disembodiment in different contexts that reckon and grapple with the continuity of colonial intervention into current coloniality of power and neoliberal exploitation. This is why she’s constituted as a reminder of colonial trauma but also as a witness of her exploitation throughout time – the forced invisibility that she’s guaranteed should not go without question.

I’m convinced this is why she becomes a productive figure to address loss and disenfranchisement, becoming a presence that resists her obliteration and evinces the fractures of whitened and whitening identity discourses throughout Latin American territories, which are originally multinational and multiethnic territories.

6. It seems like Mexican and Latin culture — really, most other cultures — have a better relationship with death than (Judeo-Christian) Americans do. Do you think that comes from a place of pure spirituality, or more of a willingness to characterize the afterlife, or something else?

This is quite a fascinating matter, because it comes hand in hand with the normalization of racialized body as a “non-body.” In short, I think some that of our allegories around death are partly testament to the organic relationship that original peoples have had with death long before the establishment of the idea of an afterlife in a Judeo-Christian sense.

However, I think that today specially, that Mexican culture as I experience it –– which is what I can attest to as a Mexican woman ––is deeply traversed with a familiarity with death that has grown from celebratory abandon to a different coexistence with it.

This factor touches upon a very deep notion of the non-male and/or racialized body as disposable. When the context in which you live almost guarantees and/or is even oblivious to your obliteration, this relationship is shifted, and it becomes a cruel but real reminder of mortality.

7. What do you think of our current “golden age” of feminine horror? Is it truly a renaissance or are we just getting started?

I think there’s definitely a fantastic moment to upset dominant narratives of victimhood, agency, pain and fear, all tenets of horror film. Perhaps it is less of a matter of renaissance of the genre as much as it is a pivotal moment to reframe the ways in which horror and the horrific are articulated through many perspectives and angles.

This mode of storytelling has been around for quite a while, but it makes me incredibly happy to see that the focus is shifting to make these vantage points visible. There’s still a lot to do, but I believe horror filmmaking and scholarship are providing a very fertile discussion regarding the need for more stances that can account for diverse experiences and knowledges.

8. How would you like to see the genre evolve from here?

I would love for the genre to keep accommodating and encouraging horror and fear as means to criticize, upset and disrupt power structures – to keep in focus the undeniable influence of race, gender, ability, class and many other factors as nuances to these experiences. Uplifting the voices of nb folx, womxn, POC, and many others, as all those whose experiences need to be told from their own perspectives without guardianship or creative “translations” or appropriations. I’m elated to think about more ways in which to think narrative, time, fear and storytelling.

9. Last question. Just out of curiosity, who’s your favorite on Dragula?

I’m torn! I’ve written on Dragula as a side project and have spent a considerable amount of time trying to pick a favorite. But perhaps, if I was made to choose, I would be Team Vander Von Odd! She’s just my absolute queen, and I can totally get behind the punkest act of puking while in Divine costume AND going all in on filth with glamour. I love Vander’s incredible literacy on queer pop culture and her creativity. I die for that ghoul.

Follow Us!