Much like its 1974 predecessor, 2019’s ‘Black Christmas’ has a lot to say about the world women live in, feminism, and toxic masculinity.

Through its nuanced and rightful rage, April Wolfe and Sophia Takal give Black Christmas 1974 a worthy successor. My wish for the new year is that, whatever you may think of the film itself, you take its core messages to heart.

It’s already been long established that Bob Clark’s original Black Christmas is extremely unsubtle in its feminist messages. It would only make sense that a 2019 version of Black Christmas would be a primal and rage filled scream at society that has done little to change how it views women.

April Wolfe and Sophia Takal take all the pent up frustration that was presented in Clark’s film and modify and mold it into their own version of Black Christmas. Unsurprisingly, they have received backlash for it, with people who so violently dedicated themselves to willfully misunderstand the messages of the movie.

From here forward will be heavy spoilers for the 2019 Black Christmas. Proceed with caution.

The 2019 Black Christmas takes rape culture and toxic masculinity to task.

From the start the film is loud and not afraid to step on the toes of those who possess fragile masculinity. It very much has the idea of sisterhood and friendship at the heart of it, much like its predecessor before it. This time we are introduced to a group of sisters who are just as loud and unapologetic as Jess, Barb, and Phyl.

One of the main characters, Riley, has shied away from life due to a prior sexual assault. Riley reported her assault and wasn’t believed and thus has gained the ridicule of not only the frat which her rapist belonged to but others on campus. She’s been branded a liar and ostracized, while her rapist is still viewed as a prince among his peers and the college as a whole. It’s a stark and realistic picture of how society has been groomed to view victims of sexual assault with more scrutiny than those that are accused.

Riley was once an active member of her sorority and campus life, but gone are the days where Riley could move through the complex hierarchy of college life. Riley is a pariah because she spoke up, speaking to why so many sexual assaults go unreported.

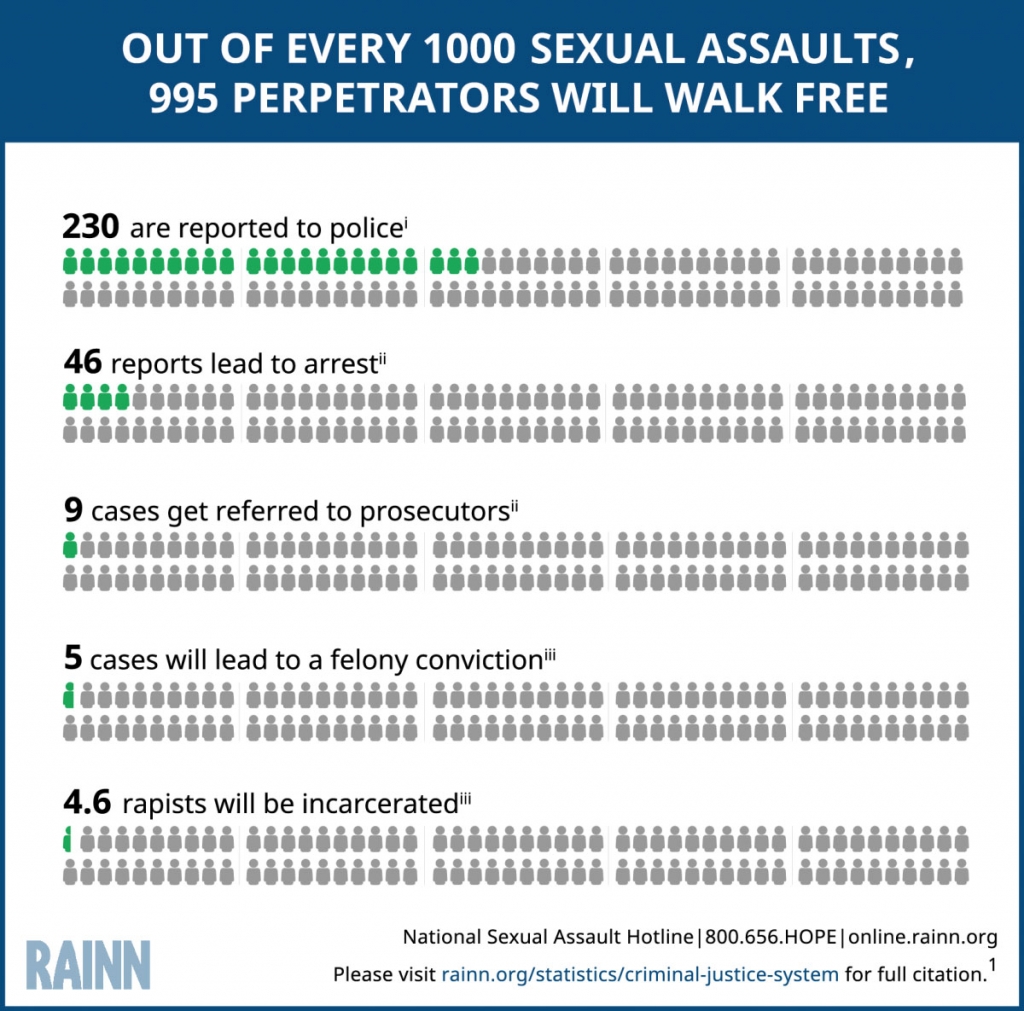

The National Sexual Violence Resource Center, NSVRC, states that in the United States one in five women and one in seventy one men will be raped in their lifetime. The Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network, RAINN, reports that 3 out of 4 sexual assaults go unreported and those who perpetrate sexual assault are less likely to go to jail that perpetrators of any other crime.

Riley’s story reflects these painful statistics.

RAINN also notes that only 20% of female college students report their assaults. Riley would be among those 20%. She reported and didn’t see the justice that she so deserved, much like many real life survivors of sexual assault. Riley is a painful mirroring of society’s enabling of rape culture by failing to take sexual assault seriously. She is not only a victim of rape when we first meet her but also a victim of unrelenting victim blaming.

Throughout the film, it becomes clearer and clearer that Riley is suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. She often finds herself in situations that cause her to have flashbacks to her assault, and those flashbacks paralyze her. The American Psychiatric Association reports that 20 to 50 percent of survivors of assault or rape will go on to develop PTSD.

In contrast to Riley’s withdrawn nature is Kris, who rivals the original’s Barb in her defiant ways. Kris is unafraid to hold people accountable for their wrongdoings and call them out. She and Riley share one of the most profound bonds in the film, both leaning on and uplifting one another. It’s a loving and realistic dynamic. At the start of the film Kris’s outspoken nature has already seen the dismantling of the bust of the college’s famously misogynistic and racist founder. When the audience meets Kris she is passing around a petition calling for the firing of Professor Gelson.

Kris is as intelligent as she is fiery and she refuses to be silenced. She has long went toe to toe with Gelson for his syllabi that contain the works of mainly white men, an action that he shrewdly defends early in the film. Kris represents students who are largely fed up with how racism and misogyny are often slyly condoned in higher education.

Kris is a part of a vital movement in academia that seeks to include the writings of people of color and women.

It’s no secret that academia has been largely white washed and the writings of people of color and women largely ignored in favor of a more traditionally acceptable white colonial tinged curriculum. Kris isn’t having any part of it, and she shouldn’t. She’s not going silently on that matter or the matter of Riley’s sexual assault. At one point she even throws water in the face of a fraternity pledge who insinuates Riley was a liar.

Rounding out Riley and Kris’s close circle are Marty and Jesse. Marty and Jesse help take part in a talent show act that Kris has staged to call out the fraternity brothers and their bad behavior. Riley aided Kris in this, but did not intend to be part of the show until Helena, one of the younger sorority sisters, is too inebriated to perform. Kris talks Riley into taking Helena’s place in the act, which is a witty song that parodies the song “Up on the Housetop.”

The lyrics are about frat brothers sexually assaulting girls and deliberately calls out the fraternity and the college for their lack of action in Riley’s case. It’s a powerful statement for the girls to do this in general, but it makes it even more powerful that the talent show is held at the fraternity and is one of their traditions. It’s also important that one of the other sororities on campus has openly boycotted the talent show due to Riley’s assault, standing in solidarity with Riley and her sisters.

Much like the 1974 version of Black Christmas, sisterhood is the centerpiece of this film and the power of women standing together and for one another.

The sisters find themselves at the center of a misogynist conspiracy where the fraternity is more like a woman-hating cult that is headed by Professor Gelson, in a bid to “restore order” and put the women of the world “in their places.” The men of the fraternity are so desperate to take dominion over women that they have turned to black magic, much like the founder of the college was rumored to have.

While facing the murderous frat boys, the sisters have to fight not just for themselves but for each other. Sacrifices are harrowingly made, one being when a wounded and defiant Marty lays her life down without another thought in order to give Riley and Kris the opportunity to run and hide. It’s a deliberate act of love. These girls aren’t afraid to die for one another if it means that they can protect what they love.

Helena is one sister that sides with the fraternity in the end, claiming that she will be taken care of. She worked as a double agent and betrays her sister, thinking herself safe by doing their bidding and taking a submissive place in their nefarious plot to beat the women on campus — and in the world at large — into submission. Helena makes a plea to Riley to take her natural place as a “good woman.”

A good woman of course is one that is quiet and pliable to the wills of men, one who exemplifies the sexist patriarchy’s ideal woman.

Helena is largely symbolic of women in real life who position themselves as mouthpieces for the patriarchy. The ones who claim that they can’t be feminists because they’re “good women” and because they “don’t hate men.” They erroneously equate feminism to misandry and act like it’s dirty and wrong to believe in equity.

In fact, one can say that Helena’s Benedict Arnold moment was foreshadowed in the scene where Professor Gelson quotes Camille Paglia in his class. Riley believes that the writer is a man due to the misogynist tone and implications of their writing. Gelson gleefully reveals that the writer is none other than Paglia. Paglia identifies as a feminist, but is far from it. Most of her writings openly decry the works of women and women’s unique and innate place in this world as a whole.

In the essay “It’s a Man’s World, and It Always Will Be” she goes as far as saying men are the architects of the world and civilization and thus it belongs to them — painting women as largely dependent on men and criticizing the idea of pointing out the shortcomings of men, period.

Paglia’s internalized misogyny has made her a perfect mouthpiece for the patriarchy.

It’s also important to note that Paglia is a rape apologist and a trans exclusionary radical feminist. She has faced backlash at the university she currently teaches at for pushing all together harmful rhetoric that endangers rape survivors and trans people.

Helena can be paralleled with the likes of Paglia. At a cursory glance, it seems that she is a part of the sisterhood. But upon further inspection, we see she is not. She is, in reality, a foot soldier for misogyny.

All in all, Black Christmas’s indictment of those like Paglia aligns the film with the ideals of intersectional feminism, the idea that feminism fights for all women — whether they be women of color, trans, gay, disabled, etcetera — instead of upholding the outdated and outright gross “feminism” of contrarian exclusionists that think feminism is only for women that adhere to their ideals.

The film isn’t subtle in where its feminism lies, and it’s an inclusive feminism that eschews hateful rhetoric and welcomes all women into its embrace.

Helena believes that she is respected and is an integral part of the frat boys’ mission. She soon learns that she is just a pawn, nothing special to them, and she is mercilessly killed when she has outlived her usefulness to them. It goes to show that no women are sacred or beloved or held in esteem by the toxic patriarchal complex. You are only useful as long as you can be used, and then you will be discarded once you have fulfilled the duty that you were recruited to do.

Women are as important to holding up the old patriarchal ways of toxic masculinity as men are. But the women fail to realize that they are extremely disposable in the process and are in fact not valued or protected in any manner.

As for the men in Black Christmas, there are two kinds that are blatantly displayed. Those that revel and benefit from toxic masculinity and those that are unencumbered by that toxic masculinity. The men of the frat are symbolic of sexist structures in the world, young men who are not held responsible for their actions and who will go on to further misogyny out in the world. The submission and silencing of the sorority sisters is merely their short term goal.

This speaks to how men in real life fail to answer for their actions and go on to lead successful lives without repercussions for their behaviors, nor do they believe they should receive any repercussions for what they’ve done. They thrive on the idea that sexual assault isn’t that bad and is just inherent to the male character, when neither is correct. They embody the idea that boys will simply be boys and that anything they do can and should be forgiven because of such.

Professor Gelson is a figurehead that encompasses toxic masculinity.

He hides his misogyny and racism behind his diplomas and his tenure. He cloaks himself in pseudo-intellectualism and dresses his nasty ideals up in complex language. He’s the smarmy sort that hopes to charm with his haphazard faux intelligentsia. He tries to escape being held accountable and even embarrassingly lashed out at Kris when she questioned the writings he chose for his syllabus.

Gelson, much like Helena, is paralleled with Camille Paglia as well. Paglia is known for dressing up her hateful misogynist worldview as a sort of intellectual doctrine when it’s highly harmful drivel. Gelson is also being faced with being held accountable for his toxic worldview like Paglia was.

The students at the University of Arts in Philadelphia passed around a petition much like Kris did calling for the removal of Paglia from her teaching position due to her outright harmful views concerning rape survivors and trans people.

The students specifically cited this particulate vile quote by Paglia concerning rape as why they were uncomfortable with her as a teacher:

“The girls have been coached now to imagine that the world is a dangerous place, but not one that they can control on their own … They expect the omnipresence of authority figures … They’re college students and they expect that a mistake that they might make at a fraternity party and that they may regret six months later or a year later, that somehow this isn’t ridiculous? To me, it is ridiculous that any university ever tolerated a complaint of a girl coming in six months or a year after an event. If a real rape was committed go frigging report it.”

Gelson also brings to mind Jordan Peterson, an extremely racist and misogynist professor at the University of Toronto, who largely preaches dangerous ideals that are upheld by the alt-right.

Peterson tries to armor his deadly and disingenuous rhetoric concerning women and people of color in his own brand of pseudo-intellect. Peterson has become sort of an icon of toxic masculinity in the way that he regards women and has created a following of deluded young men who believe that they themselves are the victims at hand when it comes to equity. He poses himself as a the fighter for the underdog male and a man who speaks the truths that people loathe to hear, when in reality he fuels men who have fallen under the spell of toxicity and works to undermine the fight for equity across the board.

Thus, Peterson has become worshipped among groups of men who identify as incels. Incels are men who consider themselves involuntarily celibate and take their anger out on women as a whole for rejecting them. In these severely disturbed men, Peterson has found a diligent audience. Gelson’s cult disturbingly mirrors Peterson’s own cult following.

On top of that, Peterson openly advocates for sexual redistribution. Regarding the case of Alek Minassian, a spree killer who identified as an incel, he said, “He was angry at God because women were rejecting him. The cure for that is enforced monogamy. That’s actually why monogamy emerges.”

He believes that forcing women into relationships with men will quell the men’s murderous urges. Peterson reinforces the idea of “good women” that are embodied in the character of Helena. He often states that a good woman is agreeable. It’s important to note that Camille Paglia considers Peterson an important thinker, showing that there is in fact great camaraderie to be had in shared outright hatred of women, much like what the film portrays. He also advocates for traditional submissive roles for women as mothers and wives.

In contrast to Gelson and the frat brothers who embody toxic masculinity, the film offers the viewer Landon as foil.

Landon is presented as sweet and altruistic. He’s not weighed down by toxic masculinity but instead displays what healthy masculinity looks like. He’s comfortable in his skin and who he is. He approaches Riley in earnest interest with no real ulterior motives. Landon respects that Riley is skeptical given her past. His honest respectfulness in turn makes him attractive to Riley. He’s not a “nice guy,” a guy who approaches Riley pretending to be nice in order to receive sexual attention from her. He really is a guy who also happens to be nice.

Landon isn’t threatened by the sorority sisters and thus is able to easily integrate himself with them and strike up budding friendships. When Landon is forced into the hazing ritual by the fraternity and finds himself under the dark magic spell that they have cultivated, he is able to break free from the pack mentality that is presented because he isn’t prone to toxic masculinity — instead standing with the girls and fighting alongside them as their equals.

Landon’s masculinity is the type of masculinity that goes unnoticed and should be celebrated. He provides a role model for men out there who seek to do better by the women in their lives. His healthy masculinity is something that should be strived for in this world. Landon represents what a future without toxic masculinity could look like.

Much of the criticism levied against this new iteration of Black Christmas has been primarily tied to its ultra feminist message.

There are viewers that have committed themselves to misunderstanding the underlying messages that the film has to offer. Many criticisms have been because the film’s messages are unsubtle. But when has being unsubtle been a bad thing, especially in the horror genre?

The original Black Christmas wasn’t subtle in the least, so why should this new one be?

If you take a closer look at most media — whether it be novels, poetry, film, or music — many of the thematic elements come through in extremely unsubtle ways. Shakespeare, the revered bard himself, was an extremely unsubtle writer. Telling Takal and Wolfe that they need to be subtle to be respected in their message would be akin to telling the members of Green Day that they needed to tone down the political messages of the album American Idiot to garner the respect of the general public. Being unsubtle does not equate to the lack of nuance.

You can criticize the acting, the dialogue, the plot twist, etc. Those are actual valid criticisms. But the messages of the film are not some great man hating plot. It’s a battle cry for intersectional feminism and for equity between the sexes and for the eradication of the tenants of rape culture. Acting like Takal and Wolfe are taking all men in the world to task is being willfully ignorant to what they are attempting to say.

My own father, who is as manly as they get, liked the movie and how, in his own words, “it was aimed at the Brock Turner types of the world.”

I am sure that we all can agree that, despite how we feel about the execution, those are in fact good messages to transmit via media.

Am I saying the film is absolutely perfect in every little way? No, I’m not. No film is. But I am saying that it is important. You do not have to like something to understand that it has inherent worth and meaning. It also does not have to be a film where you are the ideal audience for you to understand and agree with the themes displayed in it.

Black Christmas literally wants women and men to break the mold of long held ideals of what a woman should be, and it wants to eradicate rape culture and toxic masculinity. Riley breaking Calvin Hawthorne’s bust symbolizes this. It’s Wolfe and Takal saying goodbye to these relics that have been carried into the present time.

It’s time to stop being disingenuous and pretending that the film is targeting literally all men and that it is off base in its message. It’s also time to let go of the painful and dangerous societal institutions that the film openly and loudly criticizes.

Let us, as a united front, let go of rape culture and toxic masculinity and pave a way to a world where it is a safe for women to walk down the street without their keys clutched in their fists and where men can be soft without the fear of ridicule.

It’s okay if the film didn’t personally work for you as a viewer.

It won’t work for everyone. But I humbly implore that you at least respect its message and the work that went into it. Because at the core of Black Christmas is the idea of a better and equal future for us all. Equity shouldn’t be considered emasculating and saying rape and rapists are bad shouldn’t be considered radical or even a statement that can be argued with.

If you were offended by those simple messages, you should ask yourself why, and I implore you to do some much needed soul searching. There is still a chance to change for the better and undo the toxicity that has been laid upon us all by harmful social constructs.

As a new day dawns at the start of a new year — and a new decade — it’s time that we break our own metaphorical Calvin Hawthorne statue.

6 Comments

6 Records

Acid Kritana wrote:

This movie sounds horrible – also, there is either no such thing as toxic masculinity, or there is both toxic masculinity and toxic femininity.

The Angry Princess wrote:

First of all, we encourage you to watch the movie before forming an opinion. It’s certainly polarizing, and it’s quite possible you might not enjoy it at all. But it’s important to judge a film on its actual merits rather than make snap judgments. Regarding your point about toxic masculinity, that’s a phrase that is very often misunderstood and misinterpreted to be anti male, which it is not. The phrase requires careful contextualization. Discussing toxic masculinity is not saying men are bad or evil, and the term is NOT an assertion that men are naturally violent. In fact, this conversation was started by men. It was inspired by a feminist movement that had done much to unpack what might be called “toxic femininity” (think eating disorders that seek to control one’s eating and environment). After the good work feminism did to try to find better ways to teach girls about their options, men began to take notice and apply those same gender-construct theories to their own experience.

Acid Kritana wrote:

Firstly, I was planning to watch the movie. I understand that one should watch something before fully judging it. I am still planning to watch it.

Secondly, the way “toxic masculinity” is often used is quite anti-male. I’m going to be writing an article on it, so if you want to read that, I can let you know when I upload it (and give you a link).

Thirdly, if you are saying that the Men’s Rights Movement started because of feminism, I have to say, you’re wrong (maybe on accident). The MRM started in 1856 (https://ernestbelfortbax.com/2014/01/25/first-and-second-waves-of-the-mens-rights-movement/)

The Angry Princess wrote:

Thank you. We’d love to read your article when it’s published. We think this is a very important dialogue we should all be having. And we definitely understand that words can be appropriated in negative ways. Just as feminism is often used to be anti-female, equating the fight for equality to male bashing, the term toxic masculinity is often used incorrectly to imply that all men are toxic. And no, not saying the men’s movement was started because of feminism…just that some of the discussion about toxic femininity from the feminist movement infused the discussion about toxic masculinity.

Acid Kritana wrote:

Sure. I’ll be writing it soon, so I’ll let you know when it’s done. I’m writing other articles, and planning to write a manifesto/other detailing what the 3rd wave Men’s Rights Movement is going to be like (so that’s my priority), but hopefully, it will get done soon.

Yeah, feminism has been used by some for male bashing. Some other feminists (like my mom) are pro-MRA, while others aren’t necessarily pro-MRA, but are certainly pro-male. So it’s good to hear how you guys seem to be much more on the pro-male side!

Good to know that’s what you meant. Apologies if I seemed rude. I often see feminazis (and when I say this, I mean the bad kind of feminist) say the MRM started because of feminism, and it makes me a bit mad. So good to see that’s not what you meant. Again, sorry!

Ah, ok, I see what you mean now.

When I talk about toxic femininity, I don’t really talk about body issues (mainly because guys face it too, and there’s evidence that men face it just as much, and in some cases, more; for example, gay men have the biggest problem with body issues, while lesbians have the least), but more subjects like this:

How female bullies tend to use psychological bullying (while guys tend to use physical bullying)

How female bullies are worse towards male victims than male bullies are towards female victims

How female leaders tend to treat male employees better than female employees, while male leaders tend to not show this deferential treatment

How women (rich women specifically) are the vast majority of slut shamers

More

Some toxic masculinity could be:

How men tend to put each other down (for feminine things) while (sometimes) uplifting (for masculine things); but one reason this happens is because more feminine men tend to be perceived as more lazy

How male sexuality is often suppressed and hated much more (though it tends to be more so by other men [unless if you’re in Russia or Turkey or something])

More

Sorry, I haven’t really researched into toxic masculinity before, so I was wondering if you could provide a list, as well. Thank you!

Cary Elwes Is Healthy Masculinity wrote:

Saying there’s no such thing as toxic masculinity sounds like something someone whose masculinity is fragile and toxic would say. Besides, if there is such thing as toxic masculinity, then there obviously is such a thing as healthy masculinity. If you read this piece, you would know that.