In the third and final installment of our series on the evolution of the lesbian vampire, we look at the films from the 1980s through the 21st century.

In our second installment, we explored the lesbian vampire’s explosion of popularity during the 1970s. But with the end of that era came the end of her heyday. After seeing so many incarnations in the previous decade, the lesbian vampire film abruptly disappeared with the dawn of the 80s. In her analysis of Daughters of Darkness, written in 1981, Bonnie Zimmerman was already calling it a “lost genre.”

Indeed, the lesbian vampire did not experience much prominence in most of the following decades. But she never entirely disappeared. She could be found in a handful of films during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, and little did anyone know at the time that these would be harbingers of a major comeback.

The 1980s

One of the most popular queer vampire films — and perhaps one of the most popular vampire films period — is 1983’s The Hunger. While it absolutely belongs in this discussion, it cannot be labeled a lesbian vampire film.

The vampire, Miriam Blaylock, played by the stunning Catherine Deneuve, is bisexual. While the argument could be made that many of the women who carry the “lesbian vampire” label are also bisexual, it is usually their relationship with another woman that is centerpiece of the narrative. And, in cases like The Vampire Lovers, she often only seduces men out of necessity.

But Miriam has taken many lovers both male and female over the course of her very long life and seems to have felt equal, genuine love for each of them. Perhaps the most telling sign of how much times had changed is the approach to Miriam’s queerness.

A credit to the fight for gay rights over the previous two decades, LGBT characters became more prominent in mainstream film and television throughout the 80s, even if they sometimes still carried the same old stereotypes.

The vampire’s deviant sexuality has long been seen as a metaphor for queerness, and of course, Miriam is still a predator.

But when she seduces Sarah (Susan Sarandon), it is portrayed as naturally as it would had she been a man.

The Hunger is most closely related to Daughters of Darkness than any other lesbian vampire film. Miriam’s fashionable elegance was surely influenced by Delphine Seyrig’s Countess Bathory.

The two films also have very similar endings. Miriam turns Sarah into a vampire without her consent. When she is destroyed, Sarah is set free from her control and takes her place, carrying on her legacy and her vampirism.

While The Hunger is the most popular queer vampire film of the decade, it was not the only one in existence.

The 80s saw an increase in women’s independent filmmaking. Not confined by the limitations of Hollywood, women, LGBT people, and people of color found an outlet for their stories in independent film.

Two such films that carry on the tradition of the lesbian vampire are 1986’s Mark of Lilith and 1988’s Because the Dawn. The former is particularly exceptional because its lead character is a black lesbian in what was traditionally (and has largely continued to be) a very white genre. Unfortunately, given the limited technology of the time, these films weren’t able to reach mainstream audiences, and neither of them are currently available online or on DVD.

As the 1980s became the 90s, vampires continued to be the focus of popular films. The lesbian vampire, however, was still sidelined and almost forgotten. But at least one film of the following decade tried to keep her flame alive, and it drew influence from her very first appearance on screen.

The 1990s

1994’s Nadja is, in spirit if not in name, a retelling of Dracula’s Daughter. In addition to the plot similarities and visual parallels, the film’s connection to its predecessor is furthered by the use of black and white film and footage of Bela Lugosi (though from White Zombie, not Dracula) to represent the Count.

Like Mayra, Nadja hopes that her father’s death will release her from the curse of vampirism. In a scene that directly mirrors Dracula’s Daughter, Nadja plays the piano while telling Renfield, “things will be different. He’s gone… I’m free and I can live a new life… I’ll be happy.” Of course, it’s not as simple as she hopes.

However, Nadja ultimately succeeds where Mayra could not, albeit at a cost. She transfers her life force into the body of Cassandra, a woman who is in love with Nadja’s brother, Edgar. When Van Helsing and Co. show up to destroy the vampire, it is Nadja’s body but Cassandra’s spirit that is vanquished.

The downside is that the end of the film takes on a very traditional narrative reminiscent of The Vampire Lovers: the heterosexual norm prevails.

Even though the bisexual vampire, Nadja, lives on as Cassandra, she and Edgar are married and she is apparently content with being her brother’s wife and sacrificing her identity to live a normal, mortal life.

Additionally the female object of Nadja’s affection, Lucy, whom the narrative implies is a repressed lesbian, reconciles with her husband, despite their marital troubles. So while the ending is happy in the sense that Nadja gets the mortal life she wanted, there is still a distinct sense that she loses part of herself along the way.

It seems that even in the 90s, the world still wasn’t ready to let the female vampire get the girl in the end.

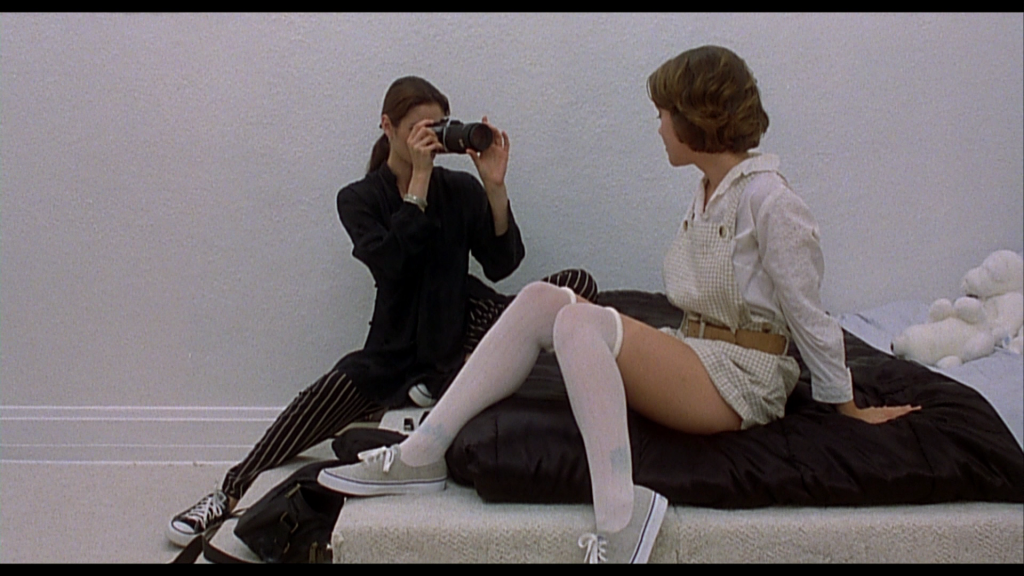

Other vampire films of the decade offered similar heteronormatvie narratives, while featuring queer relationships only briefly or leaving it entirely to subtext. In the 1995 erotic thriller Embrace of the Vampire, the lead character has a sexual encounter with another woman, but her relationship with the main male vampire is the focus of the story.

As the 20th century came to an end, the landscape of vampire films was changing, and I t would be a while before the lesbian vampire found her place in the new millennium.

The 2000s

There are tragically few films to discuss from the first decade of the 21st century. Evolving from the erotic horror of the 90s, the lesbian vampire soon barely existed at all outside of softcore porn. She could be found lining the shelves in the back room of video stores, in straight-to-video titles that were hopelessly forgettable. It seems that her previously varied incarnations had been reduced to the lowest common denominator: the sexy vampire.

That is not to say that the films of the 1970s that were absolutely capitalizing on sex and female nudity are morally superior to their successors like, say, Titanic 2000. (Yes, there is a real lesbian vampire softcore film inspired by the infamous shipwreck. The tagline is: “A vampire’s lust is unsinkable.” Let’s just say that’s one film I did not watch for this series.)

However, as I mentioned in the second part of this series, historical context is extremely important.

In the 1970s, these risqué films were subversive and, in many ways, liberating. By 2000, sex and nudity in film were so common that they had lost their original controversial nature. Throw a rock in a pool of early 2000s horror movies and you’ll hit a dozen titles that features at least one sex scene and boob shot. It had become trite and boring.

The vampire genre as a whole was undergoing a reimagining in the early 21st century. Their original Gothic nature was largely once again out of favor.

Instead, the vampire was becoming something of an action figure.

Films like 1998’s Blade paved the way for the Underworld franchise, which started in 2003 and has since inspired plenty of knockoffs. These films were heavily influenced by the spike in popularity of increasingly realistic and violent video games. Even 2004’s Van Helsing, while certainly harkening back to the Gothic aesthetics of the Universal classics, featured modern video game inspired action and special effects.

The lesbian vampire had no role in any of these new films. Outside of porn, she could only rarely be found in films like 2004’s The Sisterhood, which featured a sorority of sexy vampires in skimpy outfits put blatantly on display to titilate a young male audience. It was a low point, for sure, but by the next decade, she was ready to come back with a vengeance.

The 2010s

The current decade has seen a marked shift in the lesbian vampire narrative. Online streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Shudder are bringing independent film to wider audiences than ever, giving previously marginalized filmmakers a bigger platform and greater opportunities to have their stories heard.

And in the same way that films from the 70s, like The Blood Spattered Bride and Daughters of Darkness, bear the signs of the feminist movement of the period, many of these recent films also reflect the current sociopolitical climate.

The 2010s have also seen the most adaptations of Carmilla since the mid-20th century. The first was 2011’s The Moth Diaries, which puts a meta spin on the tale. Set in an all-girls boarding school, the protagonist believes her best friend is the victim of a vampire while reading Le Fanu’s novella.

In 2014’s The Curse of Styria (or Angels of Darkness), the troubled and lonely young Lara must choose between being “tamed” and succumbing to the patriarchal world of men, or joining Carmilla in her wild, dark world, where young girls are only saved from oppression by death. Lara instead cuts out her own path between the two, by refusing to kill herself to follow Carmilla.

But certainly the most popular recent adaptation is the Carmilla web series that ran from 2014 to 2016.

The story takes place at the fictional Silas College in Styria, where the idealistic Laura Hollis tries to save her missing roommate only to unearth a secret world of vampires, monsters, and angry gods. She and Carmilla are initially at odds, but the show gives the legendary vampire much more depth of character than any previous version of her story.

This Carmilla is given the chance to grow, not only through her relationship with Laura, but also as a character in her own right. She gets to right some of her wrongs, save the day, and get the girl, even though she doesn’t quite fit comfortably in the role of the heroine. We get to watch her relationship with Laura grow organically, while they face impossible challenges and try to save the world, with all narrative development that straight romances have been afforded for years.

This version of Carmilla is a testament to what happens when stories about queer woman are finally made by and for other queer women.

The series was followed by a feature film in 2017, which took the story back to its Gothic roots without losing any of its 21st century charm.

Another recent lesbian vampire film is 2016’s Blood of the Tribades. This film reflects current, progressive ideas about feminism more directly than any of the Carmilla adaptations. It’s very much an homage to the lesbian vampire films of the 1970s; attention is paid to every detail to give the film the look and feel of these films, but the story deliberately subverts their traditional tropes and gives women control of their own narratives.

Blood of the Tribades is a testament to what Andrea Weiss called “reappropriating” the lesbian vampire’s power.

It takes everything that makes films like The Vampire Lovers so appealing and makes them empowering, rather than depowering, for their queer and female audience. It’s stories like this, and the Carmilla web series, that are finally giving the lesbian vampire the narratives she deserves.

The Future?

So what does the future hold for the lesbian vampire?

Her popularity seems to be on the rise in a way that it hasn’t been since the 70s. Already there is another Carmilla adaptation on the way. This film will have its world premiere at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

Another queer vampire film, Bit, recently premiered at the Inside Out 2019 Toronto LGBT Film Festival. This film is especially monumental, as it expands the narrative further to include women of color and trans women in this beloved genre. Hopefully both of these films will be available on streaming platforms soon.

As we approach 2020, the lesbian vampire’s stories are growing more inclusive and nuanced.

The figure that has long existed in the imagination of her queer audiences — completely separate from her original, man-made purpose — is finally becoming one with the figure we see on screen. We can only hope that the next decade will see her grow and evolve even more, with more bloody, compelling, and fun stories for us to sink our teeth into.

And even if her popularity once again takes a decline, if there’s anything we’ve learned about the lesbian vampire in all these years, it’s this: like any good vampire, she’ll always come back.

2 Comments

2 Records