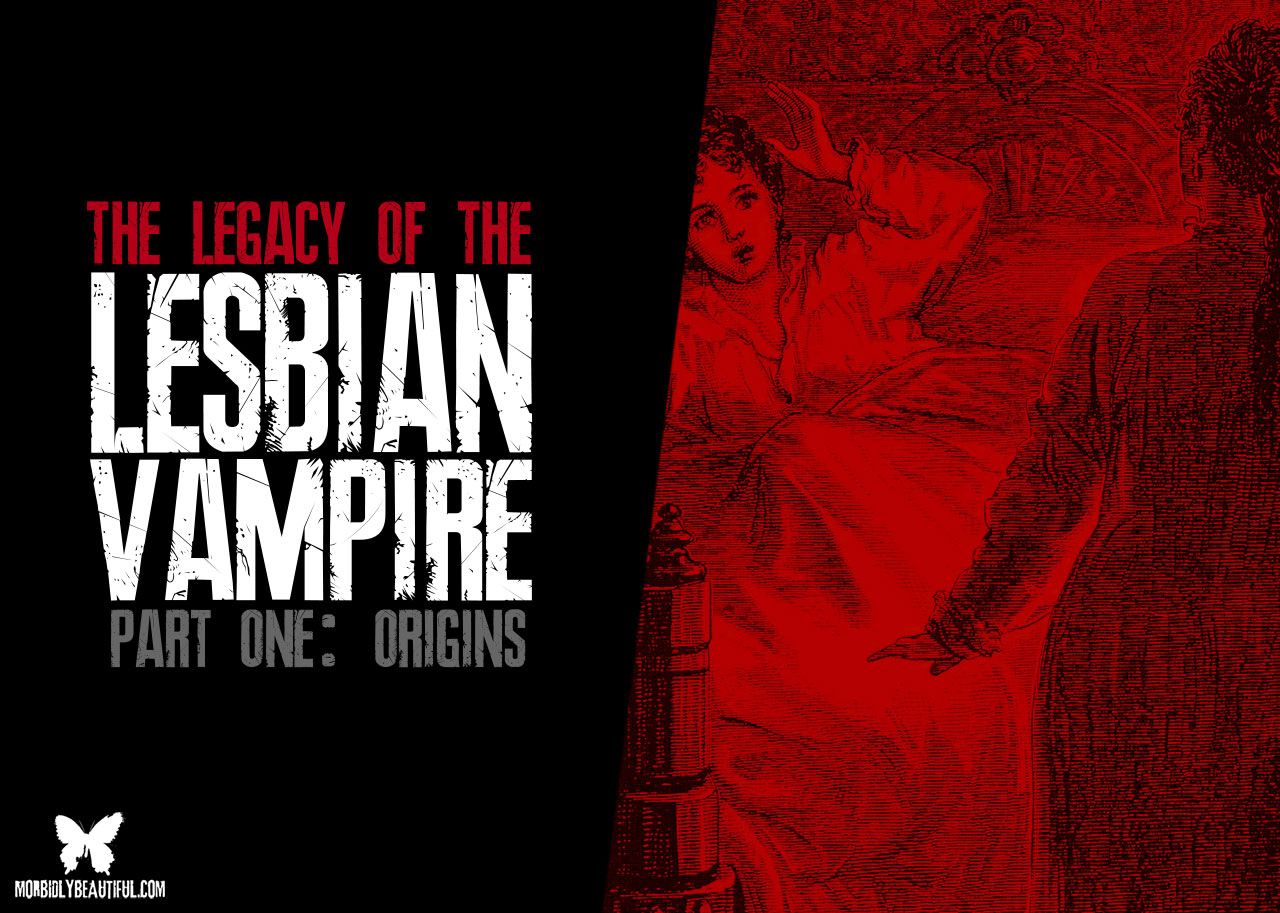

In the first of a three-part exploration of the evolution of the lesbian vampire, we examine her origins in Gothic literature and her debut on film.

“The lesbian vampire is the most persistent lesbian image in the history of cinema,” writes Andrea Weiss in Vampires and Violets: Lesbians in Film. Though written in the early 1990s, Weiss’ statement holds true today.

While the titles in the lesbian vampire catalogue are often problematic, having historically been created by male filmmakers for the voyeuristuc male gaze, these subversive films were portraying lesbian sexuality at a time when mainstream cinema wouldn’t dare. For that reason alone, the lesbian vampire is an important figure.

In the 21st century, LGBT representation in media has come a very long way, moving out of the shadows of cult and arthouse and into more mainstream film.

The advent of online streaming platforms has made these narratives accessible to a wider audience. But the lesbian vampire still persists, even when it might seem that she has served her purpose and is no longer needed.

To understand what makes her so alluring, we must go back to her roots.

The lesbian vampire is a product of Gothic literature.

Though it often explored the sublime and the dark side of human nature, the Gothic leaned more toward romance and drama than outright horror. Its supernatural elements could either be explicit or subtextual — or a little bit of both, depending on your interpretation of individual texts.

It was also a uniquely feminine genre. From Ann Radcliffe to Mary Shelley to the Bronte sisters, Gothic literature was a place where women thrived as creative forces.

Not only did they also make up the majority of the lead characters in Gothic stories — creating the enduring image of the Gothic heroine, in a long flowing gown, candelabra in hand, climbing dark staircases and poking around in forbidden corridors — but women were the primary audience for the genre as well.

While she was ultimately not created by a woman, it seems only fitting that it was in this feminine sphere that the lesbian vampire was born.

Though Carmilla is often credited as her birthplace, credit is also due to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem Christabel. This unfinished ballad tells the story of its title character and a mysterious woman she meets in the woods, Geraldine. The nature of Geraldine’s otherness is not named, but there are signs that she is a supernatural being. The intimate relationship between Geraldine and Christabel was almost certainly an influence on Sheridan Le Fanu when he wrote Carmilla.

Le Fanu’s novella is a haunting, atmospheric tale of a lonely young woman named Laura who forms a relationship with the mysterious Carmilla.

Of course, the lesbianism of the text is not explicit, but the undertones are overpowering. While Carmilla is certainly the predator and Laura the prey, at times it’s unclear who is seducing whom. Both women seem to have genuine feelings for each other, despite Carmilla’s nefarious intentions and Laura’s complete inability to truly understand her companion. It’s a story of obsessive love and vampirism, whose imagery is reimagined again and again throughout later adaptations.

Carmilla is the point of origin from which almost all lesbian vampires that followed spring.

And with the advent of cinema, she found her way out of Gothic literature and onto the silver screen. She has seen numerous incarnations, though certainly not as many as her (perhaps unfairly) more popular contemporary, Dracula.

Technically, the first film adaptation of Carmilla is 1932’s Vampyr, though it resembles the novella about as much as the 1934 Universal film The Black Cat resembles the original Edgar Allan Poe story (that is, not at all). Additionally, all references to lesbianism were deliberately omitted.

It is somewhat ironic, then, that the first popular image of the lesbian vampire in film actually has very little to with Carmilla at all. Following the success 1931’s classic adaptations of Dracula and Frankenstein, Universal Studios pioneered the horror film franchise and started churning out sequels.

Wanting to create a female Dracula figure to match The Bride of Frankenstein, they released Dracula’s Daughter in 1936.

The title character, Countess Marya Zaleska, hopes that her father’s death will free her from her curse of vampirism. When that proves not to be the case, she turns to modern psychology to help her overcome her bloodlust. Predating Dark Shadows’ Barnabas Collins — who many credit as being the first “reluctant” vampire — by thirty years, Mayra is perhaps the actual first screen vampire to openly long for a normal, mortal life and express regret over the lives she must take to preserve her own.

However, the language of the film almost makes you wonder whether she is really suffering from vampirism or lesbianism — or, more specifically, internalized homophobia. The former almost becomes allegorical as Mayra tries to fight her “ghastly” desires that consistently take the form of attractive women.

While reportedly less inspired by Le Fanu and more by Bram Stoker’s Dracula’s Guest, Mayra embodies the same otherness as Carmilla: the female other, the lesbian other, the vampire, the foreigner. It’s this otherness, and her ultimate inability to conform to the socially acceptable ideal of “normal,” that brings about her demise.

That’s the unfortunate thing about most lesbian vampires: they rarely survive their own stories.

The threat they pose to the natural order is just too much. Weiss writes that “the lesbian vampire is killed because of her active sexuality as well as her lesbianism. Seemingly sexually ‘liberated’ from the restraints of Hollywood, the lesbian vampire film appears to allow for women’s desire but always exacts its punishment.”

There are a handful of subversions and exceptions to this rule, but not often enough.

So what, then, makes the lesbian vampire so appealing?

If her queerness is so often portrayed as unnatural and predatory, if she is so often subdued and destroyed for her deviant nature, then what the hell do I, a thoroughly 21st century lesbian, like about these movies?

There’s a lot to unpack there and I don’t have the space to examine every facet of the subject. But the short answer is this: sometimes, when marginalized people — in this case, queer women specifically — so rarely see themselves reflected in media, what images there are, even if they are not painted in the most forgiving light, can hold huge importance.

And then we take those images and we transform them and we make them our own.

“Although such images are constructed within the contours of the dominant heterosexual culture… the meanings attached to the images have been frequently transformed… within the lesbian spectator’s imagination.”

The lesbian vampire is an undeniably powerful character, and Andrea Weiss suggests that it’s possible for lesbian audiences to “extricate her from her original function, and reappropriate her power.”

But it would be some time before she came into that power.

In the first half of the 20th century, Dracula’s Daughter is unfortunately an anomaly. Her appearance did not spawn an influx of sapphic-leaning vampire films. Indeed, by the end of the 1930s, the sun seemed to be setting (rising?) on the vampire as a whole. Even Bela Lugosi, the once imposing and sensuous iconic Dracula, was falling out of the limelight and reduced to reprising his most famous role for increasingly gimmicky purposes, such as 1948s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

It wouldn’t be until the late 1950s that the British production company Hammer would spark a revival of the classic monsters, with their adaptations of Frankenstein, The Mummy, and perhaps most famously, Dracula. It would be even later before the lesbian vampire was brought along for the ride.

There simply seemed to be no place for her in the post-WWII landscape. Particularly in America, increasing importance was being placed on the heterosexual, patriarchal nuclear family unit. And horror began to take the form of atomic warfare, giant insects, and aliens from outer space.

But with the dawn of the 1960s, things were beginning to change.

Subtly at first, to be sure, but changing they were. And there couldn’t have been a better time for Carmilla to be reawakened.

Follow Us!