In the second part of our three-part exploration of the lesbian vampire, we examine her explosion in popularity in 60s and 70s horror cinema.

When we left off in our first installment, the lesbian vampire had largely receded into the shadows. Her first appearance on screen, 1936’s Dracula’s Daughter, was not hugely successful in its day. And there wouldn’t be another lesbian vampire on screen for almost two decades. She belonged to the Gothic realm, something in which much of the postwar world seems to have had little interest.

But in the late 1950s and into the 60s, there came a bit of a Gothic revival.

In the UK, Hammer was turning out Dracula and Frankenstein films. On the continent, directors like Mario Bava were telling atmospheric tales of vengeful ghosts and the undead. In America, Roger Corman and William Castle were making popular horror once again — the province of haunted mansions and dark, stormy nights. This Renaissance made icons out of actors like Vincent Price and Barbara Steele.

What better time for Carmilla to make a comeback?

The 1960s saw two adaptations of Le Fanu’s novella: 1960’s Blood and Roses, and 1964’s Crypt of the Vampire. These two films are often overlooked — overshadowed, more accurately — by the films of the following decade. But they are well worth watching and discussing, and they were certainly harbingers of what was to come.

The 1960s

While Blood and Roses brings Carmilla’s story to a contemporary setting, it features Gothic motifs and imagery. The film is visually beautiful, the first of the sub genre to bring dreamlike arthouse aesthetics to the table, long before Franco and Rollin. It is also perhaps one of the earliest films of any genre to display attraction between two women, albeit in a way that mostly exists through their mutual attraction to the same man.

In this film, Carmilla has unrequited feelings for both her cousin, Leopoldo, and her best friend, Georgia, who have recently become engaged. Disappointingly, her longing for Leopoldo takes the forefront of the narrative, and her feelings for Georgia are largely expressed through a desire to get to Leopoldo through her.

An explosion unearths the tomb of an ancestor, whose spirit seems to possess Carmilla. It’s unclear if she is truly possessed, if she is a vampire, or if she is simply delusional, but she becomes even more obsessed with possessing Georgia and claiming Leopoldo as hers.

Truth be told, Blood and Roses barely qualifies as a horror film.

It contains few horror elements and even fewer vampire trademarks: there are no fangs and very little blood. That said, it’s a stunning film, with some truly remarkable dream sequences. But admittedly it ranks as one of my least favorite Carmilla adaptations, possibly (probably) because it is the lightest on lesbianism.

The other film from this decade, however, just happens to be my very favorite Carmilla adaptation.

If Blood and Roses is overlooked, Crypt of the Vampire is positively neglected.

Even in the most in depth discussions of lesbian vampire films, it gets a passing mention at most, if it’s named at all. It’s a shame, because it’s such a delightful film that perhaps captures the essence of the relationship between Laura and Carmilla in Le Fanu’s original story better than any other.

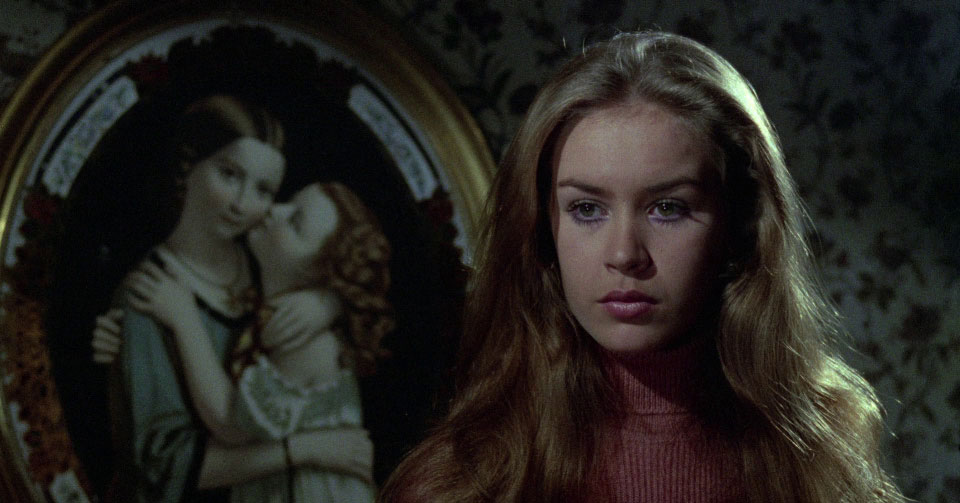

At the heart of the film is Laura, a tragic young heroine who is living under the shadow of a sinister ancestor who put a curse on future generations of the Karnstein family. Laura’s father (played by Christopher Lee, who adds an instant boost in quality to every film he’s in) is afraid that Laura is unknowingly possessed by this ancestor and bringing her curse to life.

While in many ways the film veers off into some bizarre territory, in others it remains very true to the source material. A carriage accident lands a beautiful but mysterious young woman named Ljuba in Laura’s lap, and pretty soon the two are spending their days frolicking in the gardens and gazing into each other’s eyes.

There are some highly suggestive scenes in which Laura leads Ljuba by the hand into her bedroom. The seduction is certainly mutual, and the lesbian subtext is so overpowering that it only barely qualifies as subtext. It was enough to blow me away as a confused, closested teenager who had never seen anything like it on screen before.

Blood and Roses and Crypt of the Vampire brought Carmilla back to life, far less famously so than the film that would come next.

But their value shouldn’t be understated.

Had they not pulled the lesbian vampire out of the shadows, the films of the 1970s may never have given her the chance to really shine.

The 1970s

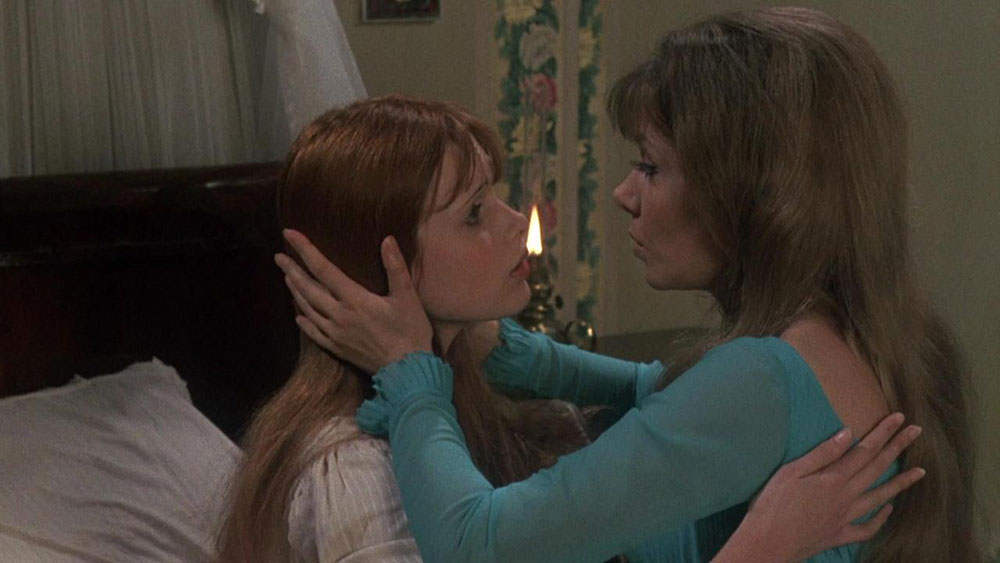

In 1970, Hammer released The Vampire Lovers and a dozen lesbian vampire films followed in its wake. Starring the captivating Ingrid Pitt as Carmilla, the film marked a shift in the narrative from the lesbian subtext of the Gothic tradition, to the open sexuality and copious nudity that would come to define much of the sub genre.

The Vampire Lovers is the first and arguably the best of what would be known as The Karnstein trilogy, a series of films that were increasingly loosely inspired by Le Fanu’s tale. In many ways the first film is faithful to the source material, though it adds a distinctly male perspective to the narrative by bookending Carmilla’s story with those of the men who would eventually destroy her.

Carmilla is a deeply erotic character.

She is positioned as a worldly, mature woman in contrast to Emma (the Laura character), who is decidedly naive, sheltered, and virginal. On the surface, their flirtation seems innocent enough, despite the viewer’s knowledge of Carmilla’s true nature. Like Le Fanu’s character, this Carmilla also seems to develop genuine feelings for Emma. But Carmilla’s plans for them to spend eternity together are thwarted, and she is eventually displaced by a bland, wholly unnecessary male hero.

Carmilla is an unnatural creature both because she is a vampire and because she is a lesbian. (It is worth noting that, while she does also briefly seduce the male butler, she does so only out of necessity. And she does not appear to feel the same pleasure she does in her interactions with Emma.)

But she is also unnatural because she is a powerful woman who is fully capable of existing independent from men.

She threatens to introduce Emma to a world where men are not in control of women’s lives or necessary for their pleasure. As Barbara Creed puts it in her iconic work The Monstrous Feminine, the lesbian vampire “threatens to seduce the daughters of patriarchy away from their proper gender roles.” For these reasons, she must be destroyed.

This idea would be explored differently by some of the following films. While it would be a mistake to label any of these films as feminist, a few of them do bear signs of influence from second wave feminism.

Two films in particular that attempt infuse some measure of feminist commentary into their narrative — with debatable success — are 1971’s Daughters of Darkness and 1972’s The Blood Spattered Bride.

In both of these films, the lesbian vampire comes into direct conflict with the heterosexual institution of marriage, but what’s interesting is that she is less of a threat and, in many ways, more of a savior. Again, how well each narrative ultimately gets this idea across is up for debate, as many people interpret these films in different but equally valid ways.

In Daughters of Darkness, the vampire is not Carmilla but Elizabeth Bathory, a fictionalized version of the infamous 16th century countess who murdered young women and supposedly bathed in their blood to stay young. In a sort of reverse Blood and Roses, Elizabeth uses the husband, Stefan, to get to the wife, Valerie.

There is a lot to unpack about this film’s portrayal of both female and male homosexuality, which is well beyond the scope of this piece.

But it’s worth noting that Stefan himself is closeted and suffering from a nasty triple threat of internalized homophobia, compulsory heterosexuality, and violent misogyny.

The honeymoon phase of his marriage to Valerie is over almost immediately.He becomes increasingly sadistic, getting off on seeing women’s dead bodies, recounting tales of them being tortured, and beating his wife.

Valerie becomes frightened of her husband, but she seems to wonder if she is the problem, not Stefan. It’s a sad truth that women are often conditioned to believe that abusive behavior from their male romantic partners is their own fault or something they should learn to accept. Elizabeth steps in to offer some insightful views on the couple’s relationship. “He dreams of making of you what every man wants of every woman: a slave, a thing, an object for pleasure.”

When Valerie runs off with Elizabeth, it should feel like liberation; unfortunately, it doesn’t. Valerie has no will of her own. She is so obviously being controlled by Elizabeth that it feels like she has fallen into a trap not entirely different from her marriage to Stefan. She still becomes a slave, a thing, an object.

The Blood Spattered Bride offers a slightly different portrayal of a woman being rescued from an abusive husband by a seductive female vampire.

Once again, the story begins with a newlywed couple. Right off the bat, we get the sense that the bride, Susan, has some subconscious fears about her husband, which are quickly revealed to be entirely founded. The sexual violence makes the film uncomfortable to watch at times, but Carmilla is soon haunting Susan’s dreams and encouraging her to murder her husband, long before physically appearing in their home.

When she does, Susan is even more drawn to her, and pretty soon the pair are embarking on a misandrist rampage. It is one of the most violent films in the lesbian vampire canon, second only, perhaps, to 1974’s Alucarda.

Director Vicente Aranda intended the film in part to be a criticism of Spanish fascism and patriarchy, and Susan’s husband exists as the embodiment of these themes. The way the men in the film view Susan and Carmilla is unflinchingly brutal in its realism.

Notably, the film is the only one of its kind to actually use the word “lesbian.”

While Susan’s husband becomes convinced that Carmilla is a vampire, his skeptical friend suggests that she’s simply an evil, domineering lesbian who has lured naive, infantile Susan away from her “proper gender role.”

Unlike other films, The Blood Spattered Bride punishes these men. When the vampire lovers are destroyed by Susan’s husband in the end, it’s framed as much more a tragedy than a victory.

The final moments of both of these films, however, suggest that the lesbian vampire will live in one form or another.

In Daughters of Darkness, Elizabeth is destroyed, freeing Valerie from her control and allowing her to live on eternally. She is seen approaching a young couple the same way that Elizabeth approached her and Stefan. The audience is left to wonder if she will use the same tactics and repeat the same cycle, or if her experiences at the hands of two domineering forces will color her future relationships.

The ending of The Blood Spattered Bride is similarly open. Despite being apparently destroyed, the film’s last lines suggest that Carmilla and Susan will live on, that they cannot truly be killed. And in an interesting twist, the final frame indicates that Susan’s husband is arrested and imprisoned for “murdering” the two women, symbolically punishing him for his transgressions against his wife.

While none of these films are progressive to the 21st century eye, in their own time some of them were quite radical not only in their displays of lesbian sexuality, but also for subversions of gender dynamics. Certainly not all or even most of these films were trying to make a statement — many of them were simply trying to make a buck. But it’s important to consider historical context even when it comes to films that some would dismiss as empty exploitation.

Surely the first three years of the 1970s saw the biggest outpouring of lesbian vampire films, but they continued throughout the decade.

And no two of them were exactly alike. Take Jess Franco and Jean Rollin, two directors who made a name for themselves with their erotic tales of sapphic bloodsuckers. Rollin drew heavily on Gothic imagery: crumbling castles, decaying cemeteries, women in flowing gowns. This aesthetic is captured most beautifully in The Shiver of the Vampires, but it can be seen even in his non-vampire films, such as The Iron Rose.

Franco, on the other hand, rejected the Gothic aesthetic and traditional vampire tropes. In Vampyros Lesbos, his vampire performs burlesque in which she seems to be seducing her own image in a mirror, as opposed to having no reflection. She spends her days sunbathing on the beach instead of sleeping in a coffin. And it wasn’t just Franco. In The Velvet Vampire — the only one of these films to be directed by a woman — the vampire lives in the desert and the film takes place mostly outdoors, during the day, with the sun beating down on her.

But the lesbian vampire’s moment in the sun would soon be over.

As the 70s came to a close, her heyday came to an end. It seemed she had run her course. Some of the filmmakers of the past decade continued to make films, such as Jean Rollin, but something was missing. The magic wasn’t there anymore. 1979’s Fascination and 1982’s heartbreaking The Living Dead Girl are perhaps his last great films.

Once again, the times were changing. The social upheaval of the past two decades had seen challenges to long-held beliefs, but by the 1980s, many believed that movements such as feminism had achieved their goals and it was time to move on. Of course, this wasn’t the case. The 1980s were not a utopia of equality, but they did see increased diversity in film of all genres. Despite this, the lesbian vampire largely returned to her pre-1970 obscurity.

But to quote the final lines of The Blood Spattered Bride: “They’ll come back. They cannot die.”

So, she would come back.

Follow Us!