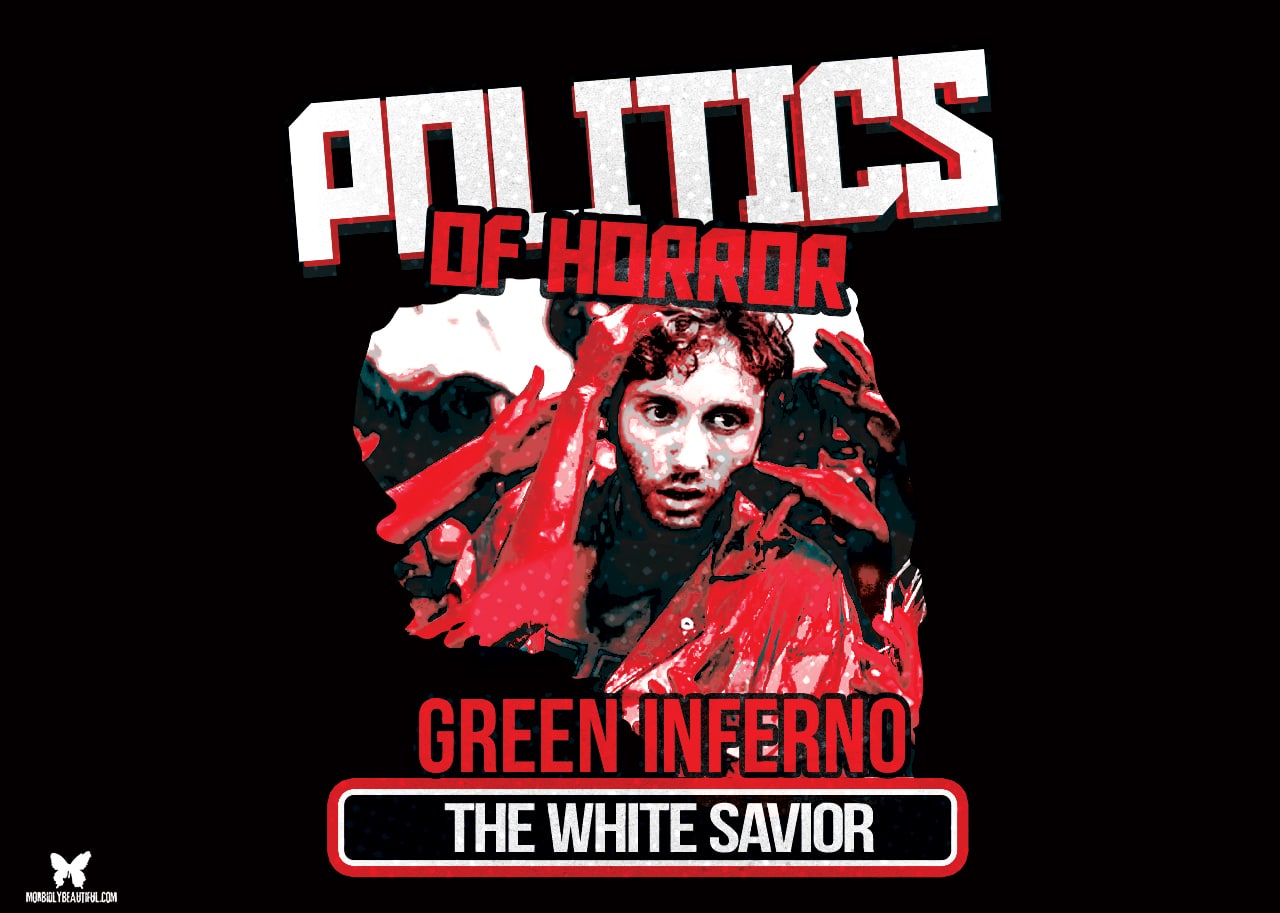

Eli Roth’s “The Green Inferno” is a brutal examination of exploitation, white saviorism, privilege, and the demonization of other.

Approximately ten years ago, before Thanksgiving fever, director and co-writer Eli Roth had a less successful, more political piece released to the general distaste of both audiences and critics, penning an intense cannibalistic work.

Winning over few new fans to the splatter genre and generally making a mess, The Green Inferno was a loss for the ratings but still served up some interesting premises when it arrived, bloody, chaotic, and screaming.

Delivered by the splatter master of the Hostel series himself, the 2013 film begins with the beautiful chirping and lush greenery of the Amazon rainforest, soon disrupted by machinery meant to deforest and clear out for development, displacing wildlife and natives.

Pan to the true injustice of a protest on a beautiful green lawn, the enthusiasm of college activism is certainly unmatched… While Justine (Lorenza Izzo) watches a hunger strike to try and get janitors healthcare, her friends like Kaycee (Sky Ferreira) are more on the bandwagon that these people are more attention-hungry and self-loathing.

In a true case of “Do you know who my dad is,” Justine comes to believe in class that her father, an attorney at the UN, can somehow systemically change something about the practice of female genital mutilation on his own with her insistence.

The naive college freshman is quickly enlightened about the reality of the situation.

She’s informed the 44th street embassy doesn’t affect all the countries that engage in this practice nor could one attorney stop a cultural tradition inflicted on thousands of young girls every year. Her outburst, however, catches the attention of a member of ACT (Activist Change Team), specifically an acoustic guitar-playing leader of the group that Justine has been eyeing.

ACT aside, steak lunch is on the menu for the UN attorney (hilariously played by the corporate face of Richard Burgi) and his daughter, and he reiterates how difficult it would be to end the issue, though Justine insists if oil were involved, it would be ended.

This seems to be enough to push Justine to visit an ACT meeting that night, where it is announced in two weeks, an untouched portion of rainforest is to be destroyed for the natural gas below and ancient tribes that dwell here and will likely be wiped out forever.

Justine speaks flippantly about how the group is to approach the demolition and is immediately dismissed by group leader Alejandro (Ariel Levy) and cannot be coaxed back by other members. Invigorated the next day, she confronts the leader about her dismissal and asks for a second chance, to which she is skeptically invited back to another meeting.

It’s laid out that the goal of this trip is to get the attention of the Peruvian government and stream their findings in the forest in order to expose the private companies destroying the ecosystem and habitat.

With Justine theoretically prepared, no one else is so convinced this trip is a good idea, and she plans for the long, dangerous journey to and through South America.

Climate Change, Deforestation, Displacement

We see symptoms and causes of climate change play out in this feature and the dramatic ways in which we try to stop it.

The Amazon rainforest is a portion of tropical forest that comprises 2.3 million miles square miles, and presently, 20% of the Amazon biome has already been lost. It is estimated that by 2030, this figure will increase to 27% of the area treeless if deforestation continues at this rate.1

Major concerns of destroying this portion of the ecosystem is a loss of species and habitats, a disturbance of the indigenous people and a disruption of their health, an increase in CO2 emissions and a negatively altered water cycle globally if the forest is continuously destroyed.

We see some of the first actions the activists took, such as infiltrating one of the work sites and chaining themselves to trees to stop the process of deforestation.

This is a long-used tactic, still being employed today if you make a quick google search as recently as this past fall a woman protested the installation of a new tennis facility in Sandpoint, Idaho by chaining herself to the 30-year-old willow tree they would need to demolish to put up the facility.2

This is the most obvious message the film takes as the activists place themselves at the front and center of every injustice within sight.

Climate change has only become more relevant with time as far as this is concerned, with a mild winter and noticeable ecological impacts over the last decade since this film was made.

The protection of native and immigrant people has become more prevalent in recent times with the political divide in this country that prides itself on both being a mixing pot and providing foreign aid.

Roth takes an easy swing at the habitat we most easily and frequently destroy that still holds many mysteries in terms of species and culture, demonstrating that the quintessential bad guy that is Big Business has a reach far enough to rob us of beings and animals we never even knew existed before they could naturally rise to the surface to be discovered.

It’s a scythe lopping off flower heads when instead we needed a till to replant.

Savior Complex

The savior complex — or, as it’s sometimes referred to, “white saviorism” — is a massive feature in this film. From the janitors, to the girls of Africa, to the tribes of Peru, these generally non-BIPOC students see their intervention as necessary in these lesser known or less gentrified areas of the world.

Activism is necessary, but the difference between activism and saviorism is motive and outcome.

An assumption that the acting group knows what the other group needs is a key factor; similarly, the acting group may see it as their “responsibility” to “uplift” indigenous communities or communities of color. A sense of superiority is present whether it is realized or not, and it becomes no longer activism or charity but a savior complex instead.

Examples include “voluntouring” — a new trend that combines tourism with light social work but doesn’t necessarily vet its candidates for the skills necessary on the ground.3

To a lesser extent, missionary work can be considered saviorism despite the fact that it can have notable positive impacts when used in community-based ways.

The responsibility, the guilt, and the sense of entitlement are present here.

We see a girl with little to no life experience who defaults to her father as a personal lifeline in an attempt to scale a massive crisis.

From the people who clean their floors to the formerly faceless tribal members they’ve never encountered, there is no group beyond their reach, demonstrative of privilege that they have the means to find and access these communities, let alone impact them.

You can see from the celebration of going viral towards the film’s beginning, nearly at the expense of someone’s life, that there is not as much gravity in these excursions as perhaps there should be.

This was a case of saviorism gone awry (or corrupt, depending how you frame it), but the question remains is there gratitude due when the favor was never asked?

It seems that’s the reward is the undying thanks of the “saved” but here, as we lead into the next section, we see instead that time and time again, we paint a nasty portrait of the unknown and vilify other less understood cultures that might appear less welcoming to what we call civilization.4

Villainization of Natives

The native tribe, of course, is done up in style with paint, ornamental piercings, bone tools, and a harsh-sounding language. Engulfing the strangers on their arrival, we witness a sea of red-painted faces overwhelm the crying pale ones as they enter the lands they were so keen on protecting against their will. Confirming Justine’s fears, the women are analyzed for purity, and some are chosen for female genital mutilation based on their level of sexual activity, classifying this tribe as a brutish one per the class lecture we sat in on earlier.

Skulls and skeletons adorn spikes, as though our imaginations couldn’t stretch just a little bit further as to what an isolated Amazonian tribe might look like beyond savagery. I can almost hear the song from Pocahontas now, “Savages! Savages!”

This has all the influence of Cannibal Holocaust written on it from the location to the presentation; the publicly displayed skeletal remains of previous visitors to this tribe reminded me of the previous documentary group whose skeletal remains were found by their rescue team in Cannibal Holocaust not far from a tribal shrine.

Despite young children bearing chickens and pigs on the group’s arrival, after the women are evaluated, the group is fed strange meat despite their objections — nothing familiar from the butchery. It is revealed this is the flesh of one of the women that escaped the evaluation and was instead slaughtered and served as a meal.

We see these indigenous people painted in a harsh light as they are supposedly part of a subsection of tribes in the Amazon that are labeled “uncontacted,” meaning living off of nature alone.

There are an estimated 400 tribes dwelling in the forest currently, some villages on the river, others more nomadic and isolated in the deep areas of the forest.5

Roth’s focus, Peru, has approximately fifteen uncontacted tribes, some of which are now trying to contact the outside world after years of solitude. The image of these tribes has been historically distorted for centuries, and papers on films such as Apocalypto, which some academics saw as another fictionalized account of native savagery and stereotypes pervading culture.6

On the whole, The Green Inferno is guilty of painting the scant tribes of Peru as brutal beings that feed on and sacrifice that which is foreign to them, but it luckily ends with a wink and a nod that this narrative is persistent, and the tribes that wish to remain uncontacted should be.

Sometimes, we should learn to leave well enough alone, no matter what our hearts want.

Follow Us!