“Traps and Tropes” was a thrilling discussion on inclusivity in film and unpacking the boxes where the disabled have repeatedly been placed.

Earlier this month, a small group of talented, disabled female filmmakers gathered via virtual meeting to present Traps and Tropes, an Access: Horror event presented in partnership with ReelAbilities Film Festival and Lincoln Center.

Hosted by award-winning filmmaker and advocate Ariel Baska, the one-hour panel focused on the lack of on-screen representation for the disabled community, the repetition of tropes in the genre that can be damaging, and what we can do to remedy this issue.

Panelists included Cashmere Jasmine, Ophira Calof, and Nasreen Alkhateeb, with opening and closing remarks by Kerry Candeloro.

The meeting was set up so that it could be accessed from the comfort of your own home via Zoom, and ASL interpretation and closed captioning were provided, ensuring inclusion for all those tuning in.

We dove into tropes immediately, with the panelists trying to define what a trope meant to them. The answer settled that it was a form of media narrative that directs themes, a storytelling device, and not necessarily a truth. Though tropes don’t always line up with reality, they help viewers situate themselves in a story and connect to characters, the caveat here is that some of these characters have been “flattened” into more one-dimensional portrayals, and audiences don’t experience the full story or identity of a character this way.

The panel also agreed that when we think about horror, some of the first associations that come to mind are “fear,” “dread,” “disgust,” and when you put differently-abled people into an environment fueled by terror, you’re likely to come out with some negative connotations.

This powerful discussion continued into examples of repetitive, damaging tropes that often appear in horror and are almost exclusively applied to the disabled.

The first trope I learned of was that of the “solo villain.”

The solo villain trope operates in which only one character, usually the antagonist, has a disability or is disability coded, and the rest of the characters are high-functioning and, by default, “good.” DC does plenty of work with the solo villain trope in the form of the Joker and Two-Face, both suffering from psychological and physical disorders and both compelled towards violence.

These tropes sometimes have real-world consequences, and one panelist who uses a wheelchair noted the looks of shock or fear on children’s faces as she passed by as they’d never seen someone like this before.

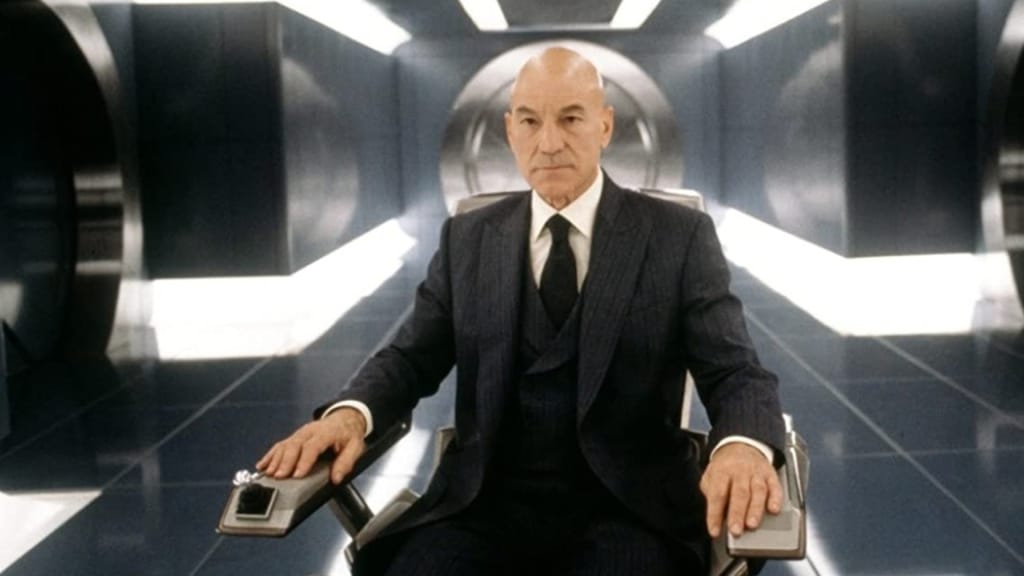

The second trope is one seen often in both horror and Marvel movies. It’s a trope called “the supercrip.” The supercrip is a disabled or mentally ill person who, through some means, is given great talent, ability, or power that somehow negates their identity as disabled.

This trope sends a message to disabled communities that to be valuable, we need to have unobtainable talent or impossible skills to be seen as equals.

Daredevil, using his blindness as a superpower, is a prime example, as is Professor X in his wheelchair but with the power of telepathy. Even Game of Thrones was guilty of this trope; when Bran falls from a tower and becomes disabled, he magically gains second sight.

The final trope that wasn’t discussed in depth as much is the trope of the “Magical Negro.”

Often, characters of color are bestowed mystical powers or connections to magic, perpetuating stereotypes. Films that appear as innocent as Ghost are guilty of this trope, using Whoopie Goldberg as a conduit for spirits.

Ultimately, the panelists offered their best solutions to the problems we currently face regarding inclusion and representation.

The ideal vision was that of an accessible world where disabled people and people of color are featured more prominently in media spaces with different stories that reflect grounded, personal truth.

Panelists said that studios could begin helping with this movement by not just hiring a disabled person or an advocate as a consultant but instead hiring people with lived experience to work in front of and behind the camera to create a more personal, truthful experience.

Audiences can show studios they want representation by choosing where they spend their dollars and patronizing independent and small-budget films featuring differently abled or racially diverse individuals.

Mostly, we need more and different stories than the same old narratives that have been rehashed repeatedly.

The panel’s final request was this: if you see a horror movie and become aware of a trope, don’t just internalize it; try to process and unpack it.

Follow Us!