Proof that superhero movies don’t have to play like theme park attractions, “Big Man Japan” makes a spectacle out of the mundane.

Since the dawn of last week, one question has plagued mankind: Are superhero movies art?

The internet is still screaming answers. Yes. No. Goodfellas is alright, but it’s no Thor 2. If you have a spare hour and more joy than you’d like, just search “MCU” or “Scorsese” on Twitter. It’s a deafening reminder, in both cause and effect, of our slow reprogramming to value opinions as the ultimate digital currency.

Why did this whole mess start? Because we just had to know what filmmakers, who can barely get their projects funded despite arguably reinventing the form, think about the genre that accounted for one out of every four dollars spent in theaters last year. Then we just had to know what the filmmakers behind that genre (and, namely, one of the largest media conglomerates in corporate history) thought about those opinions. Then everybody with a phone just had to weigh in on which side they took in the great Billion Dollar Brand vs. Guy Who Made Some Of The Greatest Movies Ever war.

In the social media courts, subjective opinion only has two verdicts: Mine and Incorrect.

That dastardly meme — with the blobby cartoon man pinching another’s lips and whispering, almost seductively, “Let people enjoy things” — swings recklessly like a pop cultural kudgel, despite the always-missing first panel inverting the context entirely. It’s not “Keep Your Conflicting Opinions To Yourself,” so much as “Don’t Attack People For Having Them.”

Scorsese can say what he wants. Marvel directors can say what they want. But painting one guy criticizing the biggest Franken-chise in history as some kind of personal attack is plain bad faith. He even admitted they’re well made, if no more risky or emotionally involving than your average theme park attraction. Good, bad, or photographically ugly, there is a house style to Marvel movies, if not modern superhero movies in general. To a filmmaker whose last movie was a three-hour drama about Jesuit priests in feudal Japan, that’s a sin in and of itself.

Big Man Japan abides no house style.

It came out in 2007, a year before Iron Man and the status-quo spectacle that’s still packing theaters 23 movies later. If anything, Big Man Japan openly disdains it. Cities are miraculously abandoned when the skyscrapers come crashing down. But our hero’s only reward is an increasingly withering montage of man-on-the-street interviews with saved citizens who consider him an unnecessarily destructive loser.

It’s not easy being the Big Man. With great power comes great responsibility and really bad PR.

Writer, director, and star Hitoshi Matsumoto only cares about those last two. Big Man Japan has no special abilities beyond being, well, very big. His primary means of attack is a steel rod that he wields with the grace of a spent paper towel roll. There’s not much ubermensch fantasy to the gig.

Which just leaves the crushing responsibility part.

Big Man Japan is not big all the time. When his country doesn’t need him, he’s a middle-aged nobody named Daisato.

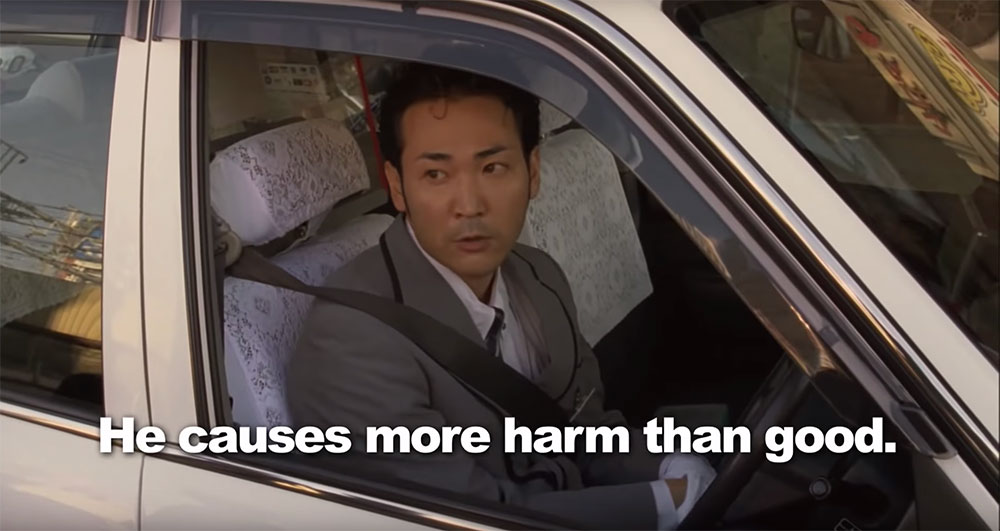

We meet him on the bus, resigned to the documentary camera crew sitting across the way, watching the ungrateful populace blur by. He doesn’t seem to mind. The only thing he feels like talking about is the travel umbrella he brought on an indisputably sunny day.

“I like that they only get big when you need them to.”

It’s a pattern in his life — he later says the same thing about dehydrated seaweed on his tofu — the agreeable convenience of things that stay small, portable, out of the way until you need them. But most people don’t wax rhapsodic about the kind of umbrellas that invert on nine of every ten pushes. They use them, forget them in the car, and throw them out the second they’re more trouble than they’re worth.

Big Man Japan, according to every bold-faced headline, is more trouble than he’s worth.

Everybody’s already forgotten Daisato.

He sees his ex-wife and daughter, at most, twice a year. I was surprised to see American Butter Belt staple, Big Boy, is alive and kicking in Japan. Less surprised that Dai-Sato almost blows his biannual chance to eat there with his family. His ex-wife doesn’t want their daughter on camera. At best, she’ll allow it if they blur out the child’s face. Dai-Sato refuses. He has a say in her life, too.

Behind a blurred face and artificially deepened voice, his daughter freely admits she doesn’t like her dad and doesn’t care that she has one.

Then the documentary director interviews her mother, who gushes about the man she’s seeing now. He’s a really great father figure. When the director asks if he can show this footage to Dai-Sato, she encourages the idea.

Even the fake movie is out to kick the Big Man when he’s down.

Like most mockumentaries, it owes something to Christopher Guest. An eclectic subject dissected in microscopic, often mundane detail through a slice of life that’s far more disheartening than anyone involved is ready to admit.

Despite the anti-Big graffiti that covers his house — the most direct of which just says “Die” — he doesn’t complain about his lot in life. One of the hardest laughs I got out of it came early, during an interview in his office, when a brick flies through the window right behind him and Daisato doesn’t even notice.

On the ground, the comedy comes from the restrained frustration and even more restrained sadness. The penitent silence of a traditional power ritual is interrupted by the director, who could use a better shot, if everyone wouldn’t mind doing it again. Daisato walks out of a salon with a fresh haircut, feeling good about himself, when the director mentions there’s a new monster and ruins his day entirely.

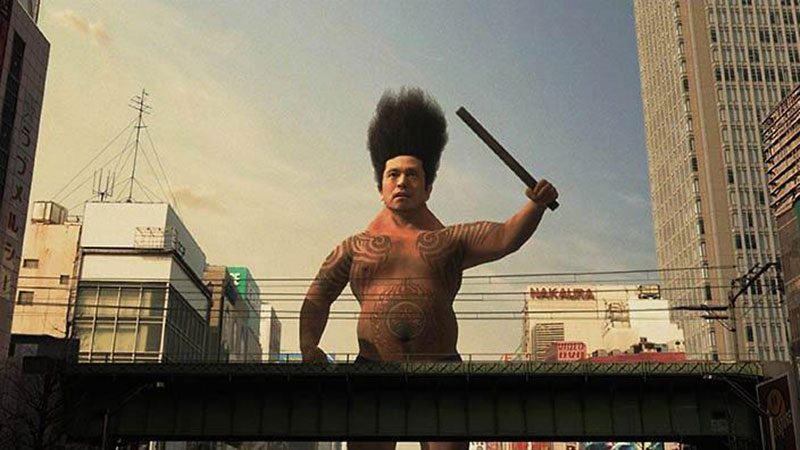

When the Big Man gets Big, it’s a Power Ranger sitcom.

The, um, embiggening process is as simple as it is inhumane. Daisato stands naked in the crotch of a massive pair of briefs and is then electrocuted until he fills them out. Sufficiently building-sized, Big Man Japan faces a revolving door of fleshy, borderline pornographic monsters. Describing any one of them would sound like recalling a week-old dream. For instance:

One is covered in mummy wrappings and has one arm, connected to both shoulders like a hoop, which it uses to snap buildings in half. Then a black spear extends from its cushioned anus and lays eggs. It has a combover.

Another looks more like a skinned chicken, with one big eye on a sticky-looking tendon. It attacks by throwing its eye like a ball and chain, and falls asleep immediately in the dark.

If you ever wondered what Hellboy looked like in middle school, he’s the final boss.

Big Man’s grandfather, Big Man Japan IV, might’ve been the greatest monster hunter of them all — and he has the memorabilia to prove it — but Big Man VI just can’t win for losing. His strategies range from running away to reasoning with one monster to make another go away. Both Big Man and the monsters are rendered with the fiberglass sheen of PlayStation 2 fighting game rejects.

All of them, even the only monster explicitly deemed female, have the faces of middle-aged men. All of these cursed things wear the weight of the world in the bags under their eyes. It’s an uncanny update of the big-suit kaiju style, with one step too far into disquieting reality. They may be clearly fake, but their faces are cruelly alive.

Not a bad thesis for Big Man Japan as a whole.

For every gag about his agent clearly getting more money from his sponsorships than he does, there’s a throwaway line about how his nationally revered grandfather got no government support when the dementia they caused set in. For every product placement tattoo he rejects, there’s a hopeful mention of his serially estranged daughter taking up the Big Man mantel some day.

It’s not always fall-down funny — though the deus ex machina finale and its stylistic whiplash will either confound or destroy you — but it’s never less than human.

Big Man Japan is a one-of-a-kind example of what superhero movies can be — one-of-a-kind — and, dare I say it, art.

(Even the part where he accidentally kills a giant baby.)

Follow Us!