“Document of the Dead” is an essential doc as much as about the joys and heartache of filmmaking as it is about the legendary filmmaker himself.

You know what’s easy? Not making movies.

It takes a dozen different artists, technicians, and craftspeople working in lock-step unison to pull off the filmed equivalent of that trick where you use a thumb to make it look like your index finger got cut off. That’s on a good day. The lower the budget, the fewer lights you’ve got to point at the thumb. And forget about that dribble of artisanal fake blood to sell the effect. You’ll get ketchup, Ambiguous Grip Reggie’s phone flashlight, and my sympathy.

All that matters, besides physical and mental safety, is what’s on screen at the premiere. But try remembering that when you’re out of canned fog and the light-up eye rigs keep winking every time the actors so much as smile. If that seems awfully specific, it’s because I was having a heck of a time remembering that when I ran out of canned fog and the light-up eye rigs kept winking every time the actors so much as smiled.

Document of the Dead opens in a later hell, the post-screening Q&A.

If you’ve never seen one, especially after a revival with some of the talent present, they’re rough. The unhinged, unfiltered Notice-Me nudging below every celebrity tweet plays out in high-definition live-action with a hopelessly captive audience.

“I didn’t have a question, I just wanted to say I liked your movie, the very famous one I paid to see specifically.” Or, “I wrote a sequel to it that I’d love to talk to you about later.” Or, the most nauseous of all, “*Attempted in-joke that somehow still falls ass-flat with one of the only crowds in the world that would get it*.”

By sheer accident, they more often showcase the filmmaker’s patience than style, savvy, or sparkling wit.

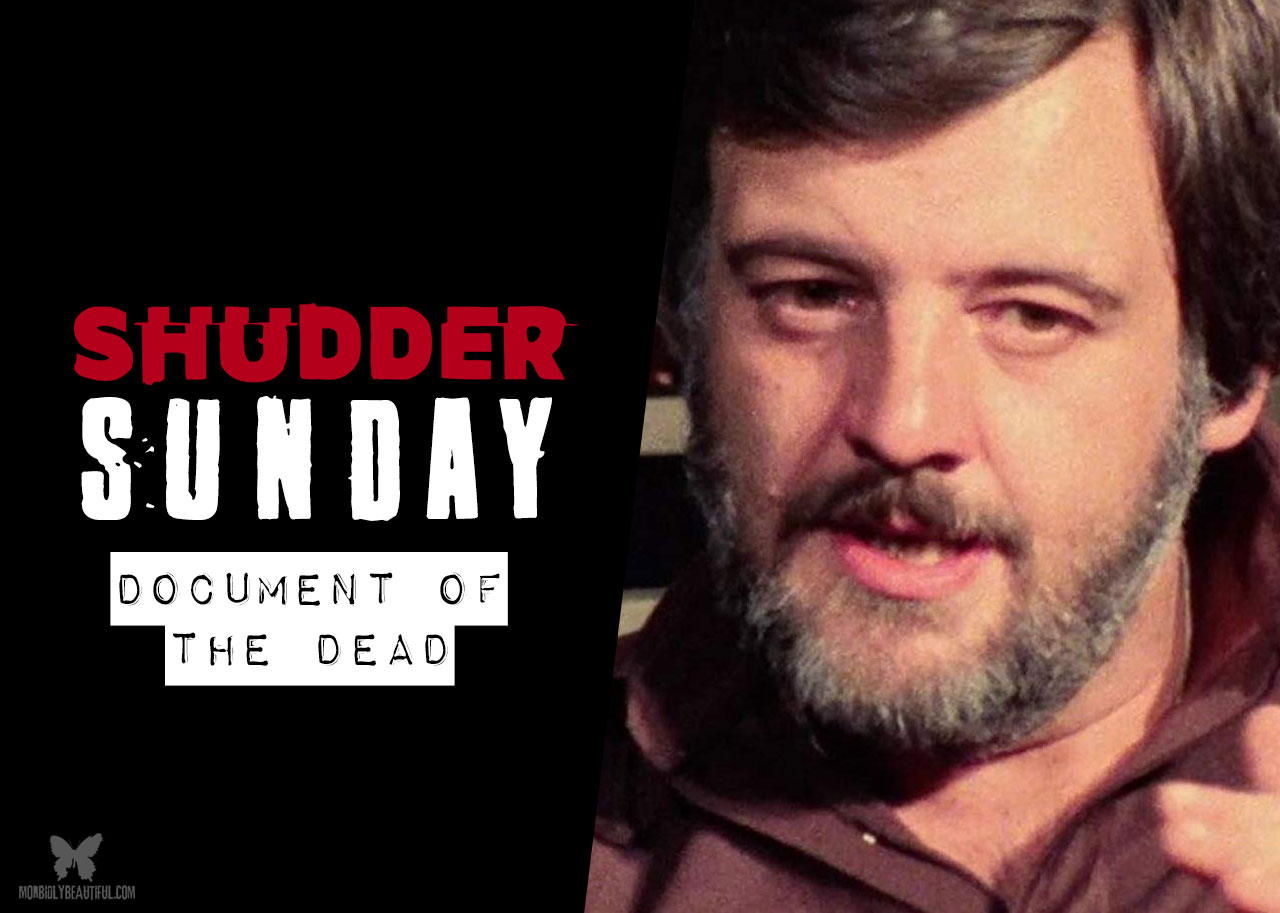

After a few false-start curios, Document picks up in 2006 with Romero aged to his full iconography — smile-creased white beard and black glasses the size of drive-in movie screens — before a packed theater. A kid asks a common question, “What got you interested in filmmaking?” And he gets an uncommon answer. George grins and asks back, “Well what got you interested?”

As a movie, Document of the Dead is a fraught piece of work.

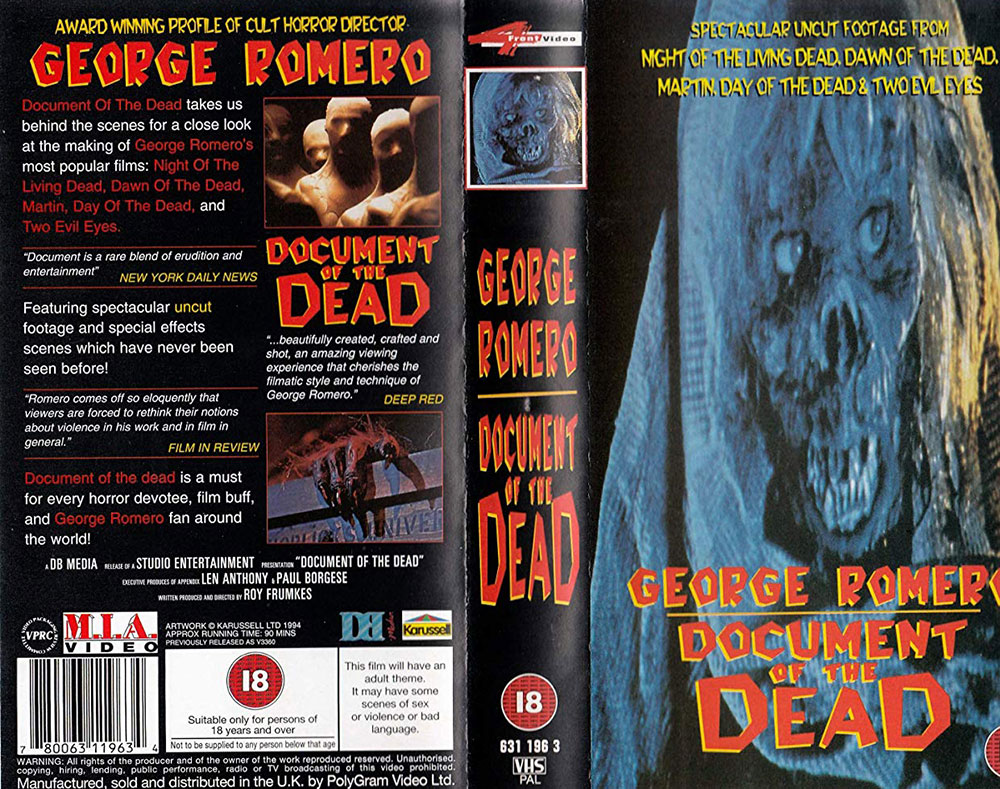

It was supposed to be a 25-minute educational film shot over a weekend on the set of George Romero’s long-awaited sequel to Night of the Living Dead. What it became was a 66-minute documentary on Romero’s house style, detergent commercials and all.

Too long for its original purpose, not long enough for theatrical distribution, Dead was dead until 1988, when new footage was shot with Romero on the set of Two Evil Eyes and the 85-minute result found a hungry audience on home video. It was expanded again in 2012 to include interviews from Land of the Dead and Diary of the Dead, for a “definitive” running time of 102 minutes.

The visual seams are admitted — an intertitle apologizes for the 32-year showcase in media formats.

But the thematic erosion is more distracting by every minute past 66.

“It evolved into something more personal and free-form in nature,” that same intertitle promises.

The director himself admits Dawn DP Michael Gornick didn’t like any of his additions past the original hour, which clumsily retrofit a piece of film history into a personal love letter. I also haven’t named said director, a film professor since the first cut, because he was fired last year over sexual misconduct allegations from multiple students.

But strip away the after-market parts — a charmingly analogue late-80s electronics store commercial is tribute enough to the movie’s legacy (“Night of the Living Deals”), so I don’t know why we had to see that much of its porn parody (Night of the Living Head) — and you’ve got a one of a kind artifact.

The irresistible, uncanny, and sometimes awkward over-the-shoulder account of George Romero facing canned fog problems across 102 minutes and 32 years.

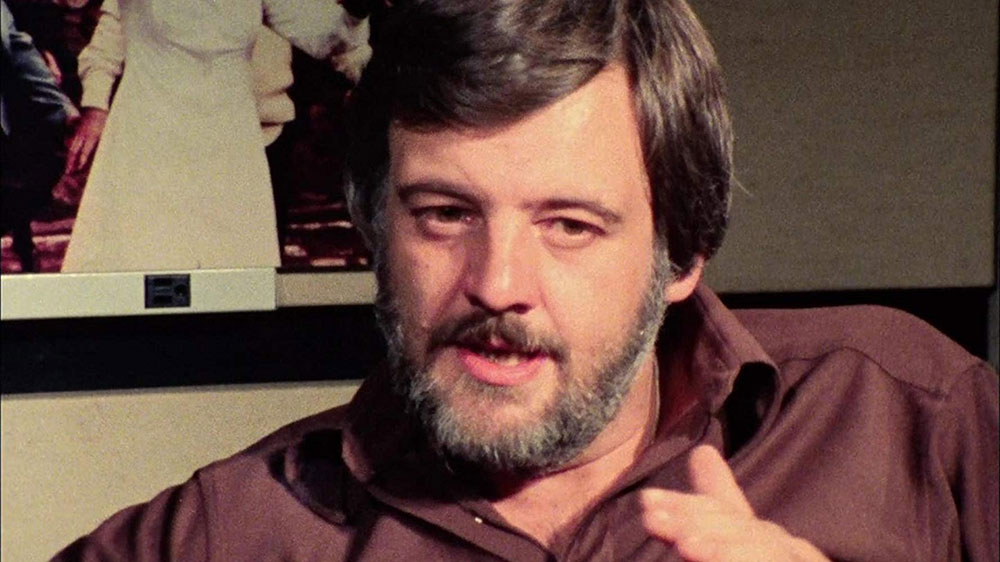

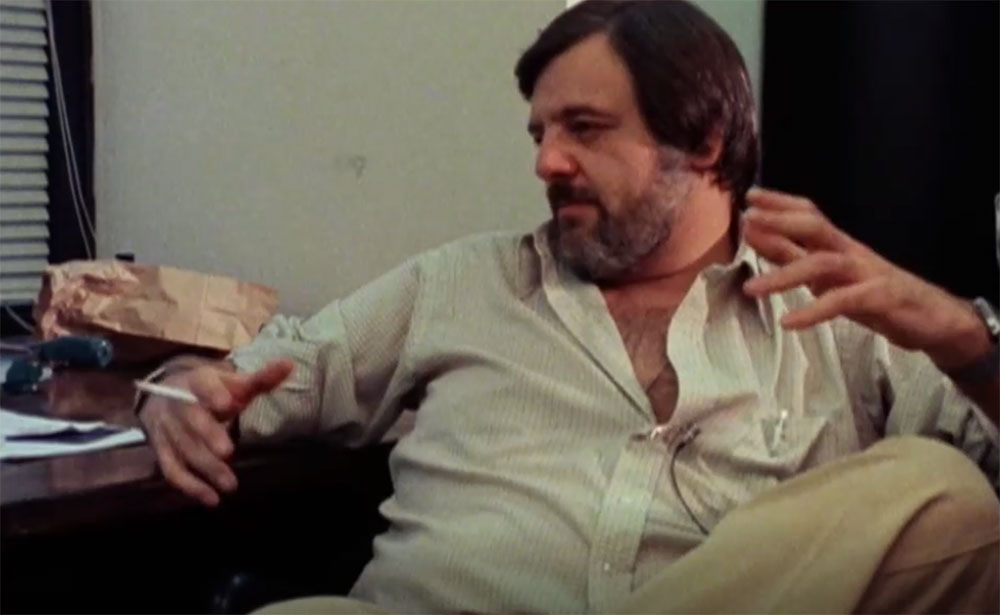

“I shoot a lot because I know I can make decisions later,” is the closest thing there is to a Romero Rule. In an interview filmed when you could still casually smoke during them, he politely shakes off a comparison to Hitchcock, with good reason. Hitchcock was notorious for shooting only what he absolutely needed.

Romero cut his low-budget teeth on industrial films and commercials that only played Pittsburgh. Style followed limitation — shoot as much as you can as fast as you can shoot it and let God sort it out on the Moviola.

Unlike the directors regularly celebrated and summed by individual shots ready to be hung on dorm room walls, Romero’s style is more about editing than cinematography, more about the rhythm than the notes.

By the time Document started rolling at the Monroeville Mall in January, 1978, George and co. had already spent two months of graveyard shifts shooting the formerly titled Dawn of the Living Dead. They had enough to make a movie. They covered the entire 243-page(!) script.

But George wasn’t done, so they were making up the rest as they went, which is why the rest included a pie fight. “It’s a very romanticized film,” says George on one of his walk-and-talks through the empty mall, intercut with a zombie tearing the skin off his wife’s clavicle.

Romero had the biggest budget of his career — $1.5 million, about half an episode of The Walking Dead — and appreciated it in his trademark way: “Having that extra weight is a trip.” Everybody involved was as carefree as they could be, besides lighting director Carl Augenstein, who points out that every time they turned the camera, he had to light a different 300-feet of darkened mall.

But besides that, the original stretch of Document is all joy. A semester of film school in fast-forward.

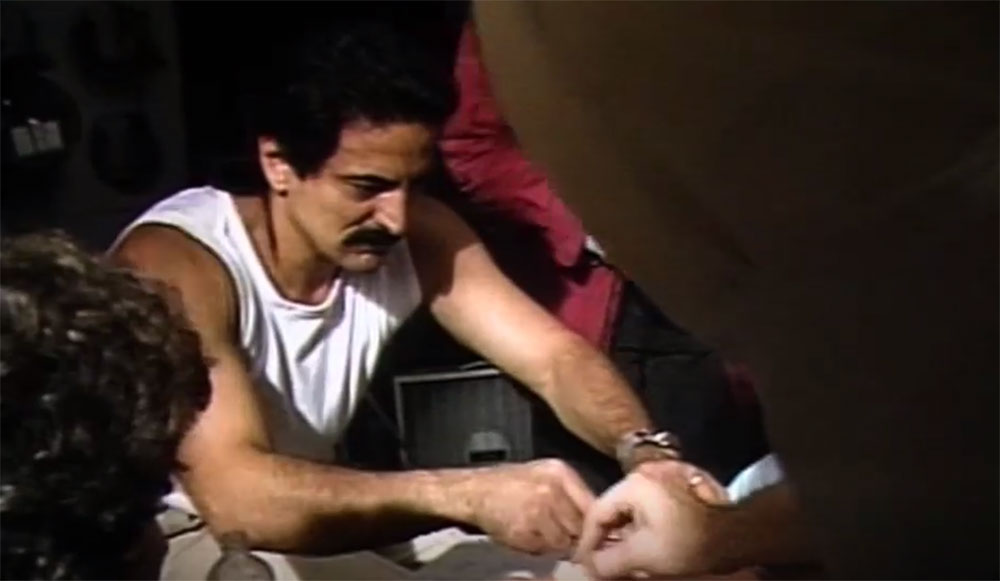

Fast-forward ten years, though, and Romero is reeling from the loss of a week’s footage, wasting a day on a single shot, and trying to quit smoking. There’s no time capsule mall to draw the eye or provide pleasant distraction. Just Tom Savini rigging up a fake chest as George nervously bounces a yo-yo behind the camera.

Take 1: The killing implement falls from the ceiling and lands in the fake chest, accidentally peeling up one of the latex seams. George says reset. Bloody shirts are swapped for clean. Same with the sheets on the bed. The rubber sternum is surgically repaired like new.

Take 2: The killing implement falls from the ceiling and lands in the fake chest. No seams. But not much blood either. George hesitates. “We need it again, I’m sorry to say.” Bloody shirts, etc., as George, already gray in the beard, says sooth on the grip truck outside. “It’s getting really hard for independents.”

Fast-forward again and George shivers in frustration after the latest blown take on Diary of the Dead, his proud return to indiedom after the biggest-budget-of-his-career, Land of the Dead. The gear is smaller. Crew, too. But it’s just not working. And this time we can’t tell what’s going wrong. Maybe it’s a performance problem, or a blood squib not firing on cue, but the result is the same.

Canned fog problems, 32 years later, on what would sadly be his penultimate film.

“What you’re doing on the surface is making a comic book,” says George, still in the grainy glory of 1978, giving another lesson with every tossed off observation. In this case, he means tone, but given his style, it’s also form. Sequences from Night are shown and laid plain as “silent cinema storytelling.” Dawn, too.

Romero’s greatest works are flesh-and-blood storyboards, each panel fitting just right with the next. A lesson all too easily glossed over by indie filmmakers — don’t perfect the notes to spite the rhythm.

“A director must be a psychologist, a storyboarder, an editor,” says the narration. “It’s a real democracy with George,” says cinematographer Gornick.

Document, or Romero more accurately, even shows the curious and aspiring how to act on a set. Not the proper terms for clothespins necessarily, but how to keep your cool when those canned fog problems arise.

But it also teaches the hardest lesson, too.

The canned fog problems never go away.

If anything, they only get more frustrating in an industry with few reshoots, less money, and no rules. There might be a quick fix — expertly squeezed baby powder or a medically questionable lungful of vape — but the solution is the same every time.

Keep trying. Keep rolling. Buy more fog on the next one.

One of George’s last lines in the documentary is at a convention, signing autographs. He likes the crowd, even if he’s not used to it, and shrugs. “Trying to find an easier way to make a buck.”

But he kept making movies because, as he told that kid at the screening, he saw that one movie when he was younger and knew it’s what he had to do.

Check out The Definitive Document of the Dead on Shudder. For all filmmakers out there, if you can survive the opening zombie-themed cover of Christmas staple “Greensleeves,” you’ll find something you didn’t know you needed to learn. Even if it’s George’s warmly chuckled suggestion to the guys behind Shaun of the Dead: “Get a life!”

Follow Us!