While it takes a backseat to Carpenter’s more celebrated horror classics, “Prince of Darkness” is an underrated gem well worth paying your respects to.

There’s a reason they called him The Shape. Sure, he has a Christian name. It just took nine sequels, reboots, and unrelated sequels to make us forget just how bland that name is. Michael Myers is still the horror icon you’re most likely to connect with on LinkedIn. But in those original credits and in that original script, John Carpenter and Debra Hill knew all they needed was a shape. Because there’s nothing scarier than the unknown.

Which makes Prince of Darkness that much stranger. Its horror lies not just in the known, but the quantifiable. What if the very nature of evil was within scientific understanding?

Turns out it takes a lot less time to understand evil than it does to understand Prince of Darkness. But a little history helps.

By 1986, John Carpenter had made his masterpieces and paid the price. Assault on Precinct 13. Halloween. The Fog. Escape From New York. The Thing. Christine. Starman. Big Trouble in Little China. Walk into any given Ramada conference center on a convention weekend and you’ll find someone willing to kill you in the name of each one. But as his budget grew, his box office dwindled.

Carpenter was still years away from a home video reappraisal, so he returned to the indie wilderness and signed a production deal with Alive Films. A lot less capital, but a lot more control. It’s how you end up with an anti-Reaganomic screed like They Live with a pivotal special effect no more expensive than a pair of Rayban Drifters.

It’s also how you end up with Prince of Darkness, Carpenter’s loving ode to quantum physics and Roman Catholicism.

At the very least, non-denominational good and evil, because the eventual revelations about Judeo-Christianity color a little outside the lines.

See, there’s a jar of ooze in the basement of a rundown church in Los Angeles. In a sunnier universe, it would’ve given rise to adolescent crime-fighting house pets. But here, in the second of what would later be deemed Carpenter’s “Apocalypse Trilogy,” this slime is bad news. Nobody knows how old it is, even the priesthood that guards it. Conservative estimates place it older than time itself.

But in the anamorphic world of 1987, it’s come under the care of Father Donald Pleasance — and he wants answers. Naturally he recruits a collegiate team of quantum physicists for the job.

The resulting cast turns Prince of Darkness into something like a John Carpenter summer camp.

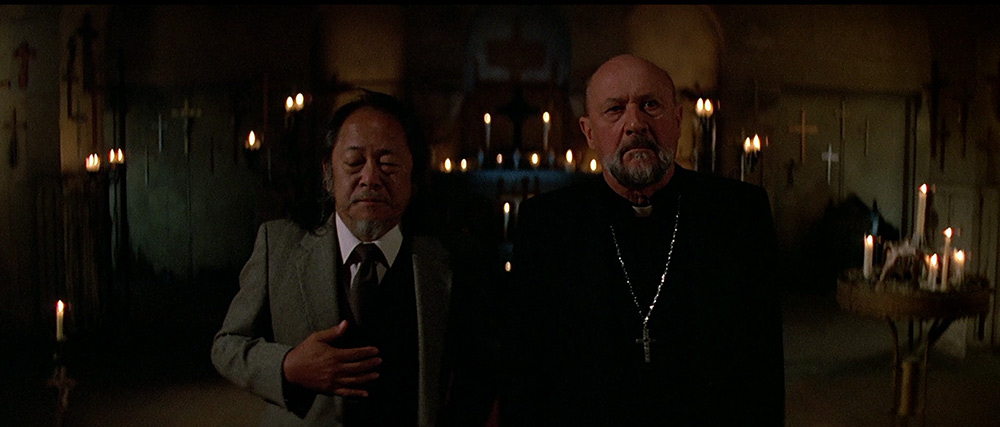

The aforementioned Pleasance provides a wild-eyed anchor for the rising lunacy for his last appearance in a Carpenter movie. Big Trouble in Little China vets Dennis Dun and Victor Wong bring their underappreciated charms to casually progressive roles for the mid-80s: Chinese-American STEM experts unsullied by math homework jokes. And there’s plenty of room for that charm to stretch out.

Prince of Darkness isn’t a long movie — barely 100 minutes — but it’s in no rush to get to the goopy parts. Once all the students and scientists dorm up in the abandoned monastery, it turns into a spooky sleepover for a while. Soon-to-be Carpenter regular Peter Jason gets to show off his impression of a trumpet. Romance crackles between the unexpected bedfellows.

I don’t know if you could comfortably call anything in his filmography a “hang-out movie,” but this is as close as Carpenter gets.

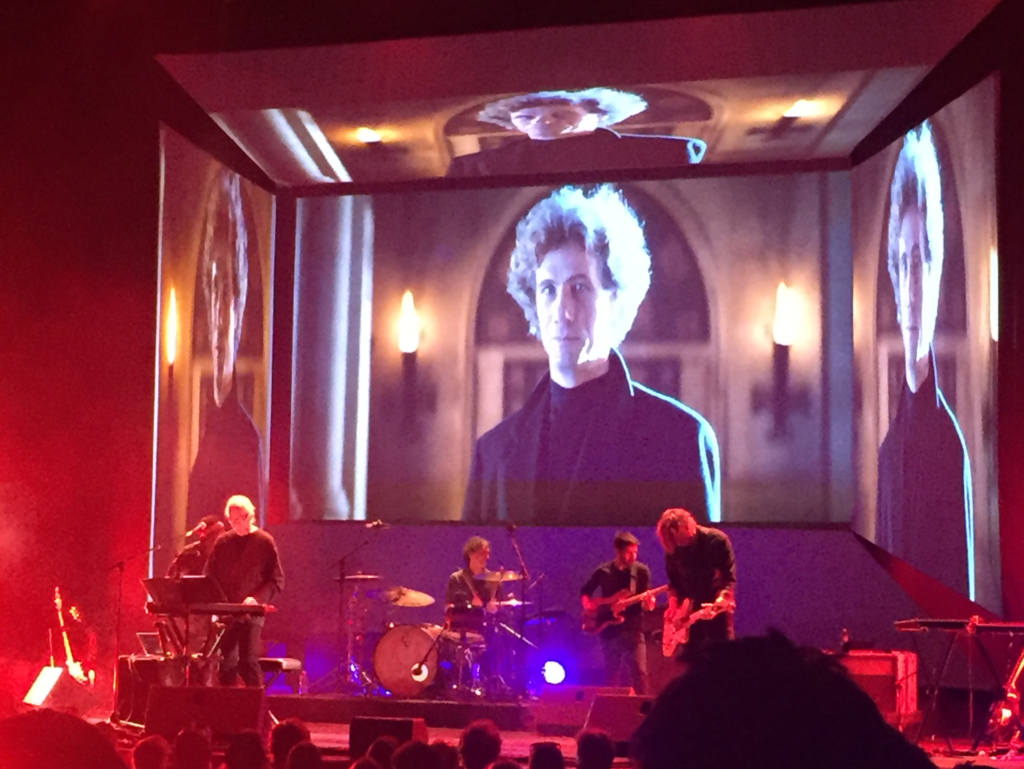

Not that you ever kick back enough to forget something very bad is going to happen. The score makes sure of that. And as indie horror creeps ever closer to a critical mass of Carpenter-inspired scores, the grave synths of Prince of Darkness feel more out of character than ever. There is no earworm. Nothing that possesses your fingers and taps out in time with Michael Myers stalking another victim.

As a follow-up to Carpenter and long-time collaborator Alan Howarth’s work on Big Trouble, it sounds downright primitive. Gone is the chest-thumping, truck-driving theme of Jack Burton. In its place is no theme, really. There’s not a character loud enough to warrant one. The hook, when it does show up, could probably be played with one hand on a Casio. But don’t mistake it for underwhelming. With Prince, Howarth and Carpenter keep everything at an electronic simmer.

It’s almost subconscious, like the sound that fills your head when you peek down the stairs into a dark basement with the only light switch at the bottom. The corrosive effect works not despite the two-guys-in-a-room quality, but because of it. Quantum physics is complicated. Horror isn’t. As the doomed crew of eggheads sweat over differential equations, the music keeps us at their speed.

The sour rumble of bad-news bass. The choked beauty of a distorted choir. The plucked keys that vibrate straight through to the hairs on your neck. These are a universal language, and few have ever spoken it better than Carpenter and Howarth.

At times, that music is the only thing holding Prince of Darkness together.

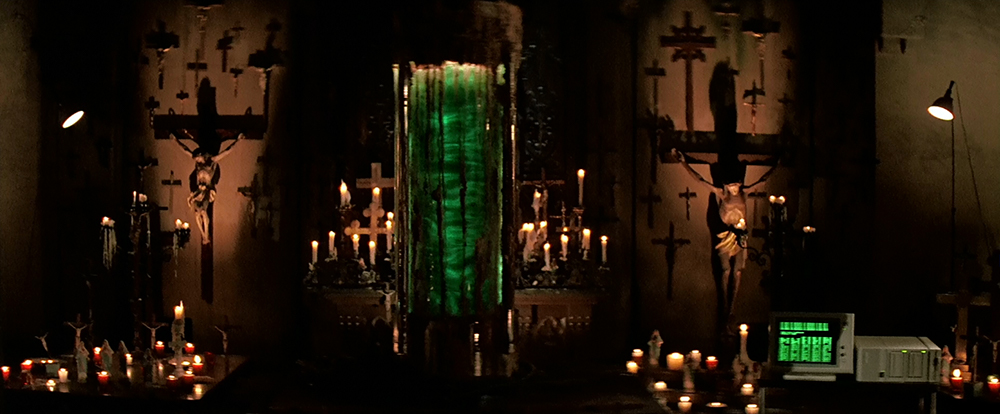

The first half of the movie belongs to science. Computers as big as fish tanks grind out line after line of impenetrable text. The theory of sending tachyons backwards in time is casually discussed over a card trick. Before long, the dusty sanctuary looks like a RadioShack sidewalk sale. It’s never heady enough to make your eyes glaze. Carpenter is a storyteller first, amateur scientist second. But it does tend on the dry side.

But as the slime starts speaking to them in ones and zeroes, and its blasphemous identity is revealed, the grounded studiousness gives way to expressionist weirdness. Ants crawl over the formerly innocuous homeless population. Liquid spills the wrong way. Magic, for one fleeting moment, works. All bad signs when you’ve just discovered that weird green stuff is actually Satan, Jesus was an alien, and Satan is a welcoming committee just like him but for the other team, for an Anti-God.

Take all the time you need to let that digest.

Prince of Darkness drops this bomb with frank sobriety and keeps on trucking into the possessions and lopped limbs and so on.

The halves piece together only because of that matter-of-fact framing. Is the world ending? Results would suggest so, yes. Can it be saved? Well let’s run some tests. Nobody panics too hard, and that’s a rare attitude in any horror. But it’s an attitude the writer is no stranger to.

Martin Quatermass is the brother of professor Bernard Quatermass, a British rocket scientist famous for his bookish handling of otherwise existential terror. Also famous for being entirely made up, like Martin. Carpenter wrote Prince of Darkness himself and used a pen name to credit his non-quantum inspiration, Bernard Quatermass, a founding father of British science fiction.

Created by writer Nigel Kneale (notice the name of the university in Prince), Quatermass was a hero for the post-war Atomic Age. A tweeded academic who observes mutating astronauts with a raised eyebrow and picks up a Browning automatic should the situation require. He made his debut in a 1953 BBC serial called, appropriately enough, The Quatermass Experiment. Its unprecedented success can be directly traced to later works like Doctor Who, The X-Files, Indiana Jones, and, yep, Prince of Darkness.

Kneale openly resented Carpenter’s homage, as he did almost every adaptation of his creation. But it remains some of the Good Professor’s only press since the 1960s Hammer cycle.

And like Quatermass, Prince of Darkness has faded with dignity.

Not forgotten. Destined to live on with the ultimate internet consolation prize: underrated.

But you can see its legacy. In the black void behind every mirror, where the helpless drift and drown, like something out of Stranger Things or Get Out. The literal Satanic panic that’s found new life in indie horror of all stripes. Or the movie’s most unsettling image, the dream. Or is it a transmission from another time? But from the same place, the door of the abandoned church, squirming with VHS fidelity.

A hazy blue light flares from within, reaching around the shape of a cloaked figure. The dream recurs and it gets closer every time. A prescient hint at the unnerving power of video distortion. But what is that damn shape?

Well, maybe Prince of Darkness isn’t entirely about the known. Maybe there are some things too terrible to try. But what’s the difference when you’re peeking down the stairs into a dark basement with the only light switch at the bottom? Now that’s something Carpenter knows better than anybody.

To paraphrase Prince of Darkness‘s most chilling line, he’s got a message for you, and you’re not going to like it.

Follow Us!