Films like “Us” prove horror can be thrilling and terrifying, while still having something meaningful to say; here are 10 of our favorite examples.

Each month, our staff picks a cinematic theme and recommends our favorite horror films related to that theme. This month, in honor of the release of one of 2019’s biggest films, Jordan Peele’s Us, our theme is Messages and Metaphors. We’ll be highlighting films that combine traditional horror elements with deeper themes about human nature and society. The following films deal with issues as diverse as political unrest to personal identity, from the dissolution of a relationship to the destruction of a civilization. Sometimes the themes are overt, while other times the deeper meaning may be harder to extrapolate — or more open to interpretation.

Check out our top ten list below and sound off in the comments if you think we missed the mark or missed highlighting your favorite message-driven horror film.

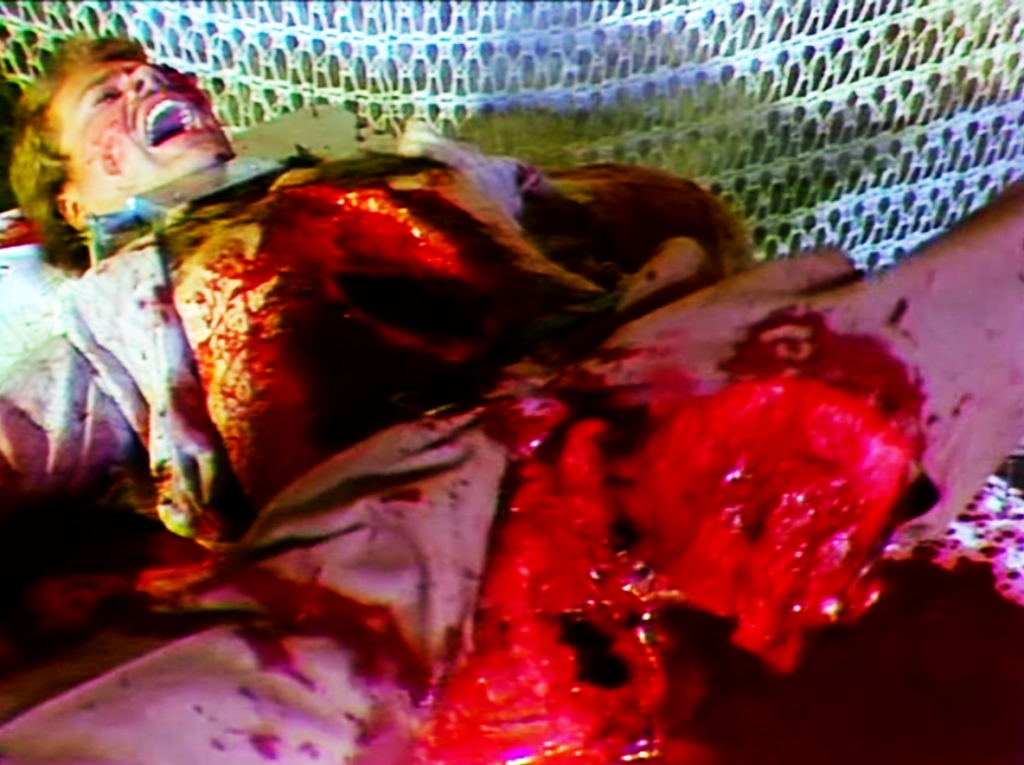

1. A SERBIAN FILM (2010)

Recommended by Megan Hopkin

One needn’t be a hardened horror buff to be aware of Srdjan Spasojevic‘s notorious A Serbian Film. With a mammoth 49 cuts implemented by the BBFC, the flick has both been demonized and heralded as horror royalty in equal measures.

The plot, in its most basic form, is nothing new: father of young family seeks to improve the lives of said young family, father becomes embroiled in some dubious matters, father thereby spirals into situations which get worse and worse until father eventually succumbs to the Bad Thing. The father figure in this tale takes the form of Miloš, a retired pornstar down on his luck and eager to make a quick buck. Under the guise of working for an “art film”, Miloš becomes embroiled in a series of dark scenes which quickly evolve into murder, necrophilia and paedophilia.

It doesn’t take a genius to work out that this film does not end with a happy family skipping off into the sunset. Serbian actors Srđan Todorović and Sergej Trifunović work fantastically on screen to cultivate a growing sense of inevitability and ceaselessness amidst a blood thumping soundtrack. With the credits finally rolling across the screen, one leaves the film feeling deeply perturbed: in search of thrills and screams, am I part of the problem?

Anyone who has seen, lest read, anything about Serbian Film knows what makes it stand out from the crowd: the hideous melding of sex and violence, and their role in corrupting youth. The dichotomy between the safety of familial ties is turned on its head early in the flick: with mothers and fathers partaking it terrible deeds all in the name of pornography.

In many ways, A Serbian Film documents the visceral effects of consumerism upon human relationships. The pursuit of self-fulfillment becomes paramount in a society of instant gratification and constantly queries as to where the line may be drawn with regards to fantasy.

Director Srdjan Spasojevic insists that the film is more than shock horror for the sake of rallying collective gasps from the viewership. He vehemently asserts: “This is a diary of our own molestation by the Serbian government. It’s about the monolithic power of leaders who hypnotize you to do things you don’t want to do”. The film serves as a sincere political allegory, with a simplistic concept articulated through the graphic scenes of brutal sex and mutilation: “the government fucks everyone”.

2. FRONTIERS (2007)

Recommended by Steven Fouchard

When the call went out for contributions to this list of ‘message movies’, I immediately thought of Frontier(s). I began to watch it for the first time in many years and was soon wondering why. The smash cut-heavy editing is reminiscent of early-‘90s MTV, meaning it looked dated even when Frontier(s) was new. There’s also too much reliance on shaky cam to create tension and, in the final moments, it makes Dead Alive look restrained – albeit without the intentional humor.

And then, slowly, I began to kind of love it again.

It’s France in the not-too-distant future – about a decade on from the George W. Bush regime. A group of youth from the Paris suburbs has pulled off a violent heist amidst the chaos of riots triggered by the election of a far-right party. They regroup at an isolated, rural inn and it’s spider/fly time as we discover they’ve fallen into the hands of a Nazi and his family who have all sorts of nastiness planned. Yeah; a literal Nazi. I guess he just sort of hung out in France after the end of the war and has managed in the interim to father a most fucked up brood.

The family is a powder keg of siblings with competing interests and resentments that play a significant part in its ultimate destruction. So, for that matter, does Yasmine (the fiery Karina Testa), a mother-to-be caught up in the horror. Papa Nazi doesn’t love her obvious ethnicity but the family desperately needs a genetic refresh, so she’ll just have to do. Yasmine’s put through the ringer to be sure but has also been literally showered in the blood of her antagonists by the end. Her battle is the cathartic heart of this movie.

Back to the Nazis though, because, without them, this is really just a Gallic Texas Chainsaw riff. As I’ve said, I don’t think writer-director Xaiver Gens had tongue in cheek when constructing the film’s climactic (and pretty hilarious despite itself) grand guignol spectacle.

I’d still argue Frontier(s) is savagely satirizing the far right.

This family of the ‘master race’ is as diseased physically as it is interpersonally. The nominal matriarch, kidnapped from another family as a child to conceive and bear scads of little Nazis, is now hunchbacked and broken. As portrayed by the sympathetic Maud Forget, Eva is fragile, doll-like, and has retained a basic humanity despite her circumstances; another innocent caught in the fascist meat grinder. And she’s produced an indeterminate number of absolute monsters – feral, almost zombie-like offspring who are mostly hidden until the end. Like so much of Frontier(s), they’re not subtle, but they do the trick: Here be dragons.

Frontier(s) defangs fascists by making them a cartoon; objects of mockery, rather than fear. It declares their ideas to be, like this family, diseased, distorted, and finally, self-defeating.

3. CABIN IN THE WOODS (2012)

Recommended by Vicki Woods (LA Zombie Girl)

I love The Cabin in the Woods. There has been a lot of debate if it is an amazingly deep and allegorical film, or just an average horror comedy. When seen for the first time, it can throw you off with what you think are simply tired character tropes from hundreds of other films. But notice the control room and start watching for clues. The idea that someone was changing the outcome of the story from a control room blew my mind!

The basic plot of the film has been done many times, and the characters are as cliché as it gets. We have the stoner, the jock, the slut, the nerd and the virgin. Then they go and do the most stereotypical thing they can do, go to a cabin in the woods (homage to The Evil Dead), despite the warning from the local old guy, the harbinger, warning them that something bad is gonna happen.

But these tropes are used on purpose. Boring and predictable, they can then be manipulated to be exactly what is needed for the ritualistic ceremony that is taking place literally right underneath them.

Everything in our lives can be changed by the choices we make. In this film, the objects that the actors pick up or the decisions they make, change the outcome of the film. They are puppets, and the caretakers of the ancient Gods below change things to make them do what they want them to do.

So, who are the old Gods? We are! The audiences going to films. No longer satisfied by simple stories, we are desensitized. It takes more and more blood to make us happy. The underground facility is the movie studio, and the directors are a reference to writer/directors Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard needing to make successful films. The directors pick the appropriate monsters and make the actors do all the stupid things we the audience always wonder why they do. The studios continue to make the same old stuff because people buy it, that’s why.

So, is The Cabin in the Woods simply a metaphor about Hollywood and the movie-making machine? Or maybe it’s even more complex? Is the entire movie a Lovecraftian type tale about our society and that we are under the domination of dark powers that we can’t control (they control us)? A very secret and high-tech occult secret society? Our own government in action? It is up to interpretation.

I found The Cabin in the Woods to be amazing. It changed the way I watch all films. Why would anyone go to a place that you know will be creepy and a mistake? Because that’s what the Gods want! Also check out all the monsters in the containment cubes, they are all a reference to either a classic monster or a particular horror film. It could take many watchings to spot them all! It has transformed my perception of movies completely.

4. DAWN OF THE DEAD (1978)

Recommended by Jamie Marino

Here I am at the “D” section of my movie library. It isn’t difficult to locate what I want to watch. It’s in a thick black slipcase with raised red lettering. I turn it sideways so the spine faces upwards and shake gingerly, yet with intent. I need some warmth in my life tonight, so I’m going to watch Dawn of the Dead.

Dawn of the Dead is like my comfort food. It’s like Olive Branch breadsticks, Old Forge pizza, or mom’s blueberry cobbler. When I watch it, I feel cuddles inside, like the screen is swaddling me in warm bloody gauze. At times when sadness bleeds out of my heart, Dawn of the Dead holds my arteries tightly closed. A horror homestead for my soul. I know every scene, every camera angle, every word, and every note of the music by heart. Quite often I catch myself reciting lines with the characters or humming along with the music.

The musical score by Goblin is timeless. It has that creepy 70’s fuzz, along with an unforgettable melodic mix of haunting electronics and blood-curdling percussion. The fact that Bruno Mattei stole it for his splattery, sickening, and scuzzy Zombie Creeping Flesh (1983) makes me love both movies even more. And once you’ve heard “The Gonk” it will never leave your brain.

The task at hand, however, is not to geek out over Dawn of the Dead. The mission presented to me is to point out the grand and glorious metaphor of the story. I don’t want to be a high-and-mighty horror academic and say the irony of the whole thing is obvious, though. Some people just don’t watch horror that way, and that’s rockin’ right-on with me!

At the time (1978) the powerful tendrils of Capitalism, Consumerism, and the ravenous need for “stuff” was beginning to tighten around the necks of America. Romero wanted to protest and poke fun at this situation.

It was such a different time back then. During the scene where our main characters first encounter the shopping mall, they aren’t even completely sure what it is. But the massive parking lot is filled with moaning, wandering, and diseased zombies. And once inside the mall itself, the group encounter large crowds of them walking aimlessly around, tripping over water fountains, knocking over displays, and not having a clue how to ride an escalator.

Like we, as a society, were becoming, Romero wanted to use zombies as a metaphor. The Consumerist contagion was spreading like a virus, and everybody was getting it. Society itself was falling apart, and Romero linked it all to the reflection of mankind as a mindless, virus-spreading John Q. Public.

Once inside the mall, our heroes decide to set-up for an indefinite period of time. After they clear the entire mall of wandering zombies, they become hypnotized consumers themselves.

“You should see the stuff we got. All kindsa stuff!”

It is obviously a damn near perfect place to shelter in and wait out an apocalypse, but Romero shows us that even the ones with clear and responsible heads will be seduced by all the “stuff” up for grabs and ruin it somehow. There are occasional moments of genuine zombie humanity, such as when Fran has eye contact with a zombie admirer, or when a zombie grabs a rifle and refuses to let go of it. He can be seen in the background for the rest of the film holding it upwards with pride, as if it were an Olympic torch.

But just like Baphomet says in Nightbreed, no home is forever. An army of sadistic bikers break into the mall and destroy everything they see, just for the hell of it. They raid every store and mindlessly steal everything they can get their hands on. Even “stuff” they clearly don’t need, like a dress shirt and tie. But they don’t play it safe and respect the surrounding danger the way our heroes do, and they end up paying for it with their lives.

I’ll bring it to a close by saying Romero showed us several different modes of survival our society may descend in to when left to our own lawless devices. I point that out because, although a zombie apocalypse is clearly a tragedy, our heroes and the biker gang were enjoying the hell out of themselves. Just like what Flyboy said passing over rural Pennsylvania, “Those rednecks are probably enjoying the whole thing.”

And as the copter flies away at the end of the film, I can’t help but think “I wonder if they got their bag of hard candy.”

5. THE SKIN I LIVE IN (2011)

Recommended by Tavera del Toro

Pedro Almodovar films deal with a legion of overtones and ambiguous descriptions. The title itself is a nod to the idea that we all have to live with who and what we are, regardless of what we may demand or wish.

The central figure in the film, Vincent, is a man forced into a sex change (becoming Vera) by a vengeance-seeking surgeon, Dr. Robert Ledgard (played by Antonio Banderas). He becomes the captive of the doctor’s skin/plastic surgery tests. While the initial phase of the film focuses on revenge (touching on forced feminization), the film nibbles on societal attitudes of gender and requiring people to comply with gender roles and identification.

While the overt issue is a man being forced to live as a female, the film is relatable to everybody. Who hasn’t wished to appear slimmer, more fit, more beautiful? Yet most of us continue in our “imperfect bodies and faces” and live life. We remain cornered in our own particular prison. But still, we work and lead our lives, struggling to perform while seeking to escape public review and ridicule.

The doctor tries to seek justice for his family’s tragedies; he kills and forces surgeries to create his world of law.In his attempt to control his world, it only isolates him from reality. Unfortunately, he becomes like other mythical characters: he tries to play God and similar to the Pygmalion legend, he falls in love with his work, who he creates in his wife’s image. The question, why would you transform the man you’d blame for your daughter’s death into the clone of your dead wife, who has left you for your estranged brother?

Dr. Ledgard lost his wife and demanded to recreate the love between his wife and him, to achieve a second chance at happiness. The doctor is cold and acts without emotions until the point at which he explodes into violence when something reminds him of his dead loved ones — he is a broken human.

However, he doesn’t fall in love with a man; the doctor turns a man, a person, into his own toy. He doesn’t realize you can’t change a leopard if you remove its spots; it is still who and what it was beforehand. And you can’t change a person if the person has no wish to be changed. No matter how much the doctor tries to recreate his life, he too can’t escape his true nature: a control freak, a perfectionist.

The film skirts the transgender issue and the question of whether surgical methods can make you a female or male. Instead, it concentrates on one aspect, one that transgender and Cis people all can agree on. The film explores the notion that, no matter what you do to alter your face or your physical appearance, you never alter the authentic you. No one can force you to be what you’re not. The “true you”, or the you that inhabits your mind, is always the same.

Since your outward identity has no relationship to what you think in your mind or your gut, it minimizes the value of gender — you are what you think you are. However, you’ll negotiate with the repercussions if the dichotomy between the true you and who you appear to be varies too much. That is the part Almodovar leaves out in the end. How Vincent will now cope now that he has been turned into Vera remains a mystery.

6. THE BURNING MOON (1992)

Recommended by The Dedman

Olaf Ittenbach’s 1992 horror/gore classic The Burning Moon, on initial glance, would appear to be nothing more than what the cover suggests: depravity, sexual violence, torture, blood and gore just for the sake of being as gross and nasty as it can be — simply because it can be. But nothing is further from the truth. The drug crisis around the world was really horrific in the late 80s and early 90s, especially when it came to heroin abuse, death and crimes. That is the hidden story behind what many consider to be Ittenbach’s most provocative film and what fuels the nightmarish images that burn through the screen. The film certainly took many by surprise upon its initial release and still does to this day.

The film tells the story of a juvenile delinquent named Peter (played by Ittenbach) reading two highly gruesome bedtime stories to his young sister, the first involving a blind date who turns out to be a serial killer and the second following a raping, murdering priest and the murder of the suspected killer by an angry townsperson, who is then sent to Hell and tortured. Peter is forced to watch his sister as his parents want to go out for the night. Furious, he injects himself with a dose of heroin and tells his horrific tales in hopes of scaring his little sister. But while in the throes of his hallucinations, he winds up butchering her, oblivious to the fact that he is basically telling her his hallucination as he is seeing it.

You can look at the first tale as an example of Peter’s rage while on the drugs. Earlier in the film, we see him involved in a street fight, and then later using in order to hide the pain and fear of the situation. The violence we see in the first story can be seen as his anger towards his family for having to stay home and watch his kid sister. The second story can be looked at from the perspective of Peter being the suspected (but not the actual) serial killer.

Stories from addicts of heroin equate their suffering as feeling like being in Hell, being tortured. Real life becomes Hell. To this very day, there are people who see heroin users as the worst kind of people who are a plague on society. There are people who believe these addicts deserve all the Hell they experience while using. If you can take nothing else away from this film, it is the fact that the suffering of others can come in many forms (especially chemical), and that some people can’t shake their addictions — no matter how hard they try or how much they may want to.

7. GODZILLA (AKA GOJIRA) (1954)

Recommended by Patrick Krause

Japanese film company Toho has produced 32 GODZILLA films. The films have portrayed Godzilla as a force of nature, a genetic freak, a destroyer of cities and humans, and a children’s hero. Godzilla has also been turned into an anime mini-series that was shown on Netflix, and Godzilla once starred in a children’s cartoon show. Godzilla even battled basketball legend Charles Barkley in a basketball game for a Nike commercial.

It’s hard to believe that this worldwide sensation started out as GOJIRA, a Japanese monster movie about the fear and anger in Japan over the H-bomb and nuclear testing.

On March 1, 1954, the tuna fishing boat Lucky Dragon No. 5 was sailing near Bikini Atoll, the island the United States was using for nuclear testing. There’s some dispute about the location of the boat, whether it was in the safe zone our within the test boundaries set by the U.S. What isn’t in dispute is that the 23 crew members of the boat were stricken with radiation sickness shortly after being exposed to ash that resulted from the test explosion. One crew member, radioman Aikichi Kuboyama died in September of 1954 from exposure to the blast radiation.

Japan was occupied by Allied Forces after the end of World War II in 1945 until 1952. During that time, according to Japanese film critic and historian Tadao Sato, the U.S. promoted freedom of expression and speech except for one subject: the effects of the h-bombs on Japanese cities Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Once freed from the shackles of the allied occupation, the Japanese were free to express themselves and the events at Bikini Atoll brought up the memories and fears of the h-bombs in World War II.

The monster, Godzilla, in Ishiro Honda’s GOJIRA (aka GODZILLA) is a manifestation of the Japanese fear and misgivings over continued nuclear testing. Godzilla represents the unleashed and uncontrollable power of nuclear energy, destroying everything in the surrounding area indiscriminately. Godzilla can also be viewed as a representation of the anger of the Japanese people. Godzilla is unleashed due to nuclear testing and part of the reason he targets Japan is because it is the country’s ships, boats, and weapons that have destroyed his underwater layer. Godzilla is Japanese anger id run wild against the government, scientists, and the military complex.

GOJIRA, and the franchise spawned from that original hit movie, is incredibly entertaining as a simple monster movie. But look a little deeper and there’s something much deeper and darker going on. It’s a message from Japan to the world about the dangers of nuclear power and those who wield it.

GODZILLA/GOJIRA is available as a 2-disc DVD and 1-disc Blu-Ray from The Criterion Collection. The set also includes the 1956 American reworking of the original, GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS.

8. THE BROOD (1979)

Recommended by Danni Darko

David Cronenberg’s real-life rage takes shape in his 1979 film, The Brood. After the highly provocative, visceral releases of Shivers and Rabid, Cronenberg went on to create an equally terrifying but incredibly personal production with his third feature.

Like many movies in my life, I initially took on this one when I was far too young to do so, but I distinctly remember being scared by those creepy fucking kids. Scared and entertained. It was only as I became older and experienced the pain of several failed relationships (and later learning some of Cronenberg’s thoughts on the film) that I realized The Brood was this magnificent diary-like entry for the filmmaker. David and his wife at the time were embroiled in one heated battle over their daughter, Cassandra. Much of the same is told in the film, but since it’s Cronenberg we must also include pint sized monstrosities, radical therapy sessions, and violent deaths.

Frank Carveth (Art Hindle) is desperately fighting to retain custody of his daughter Candace (Cindy Hinds) as his estranged wife Nola (Samantha Eggar) is undergoing an intensive, controversial new type of therapy under Doctor Hal Raglan (Oliver Reed) at the Somafree Institute Of Psychoplasmics. Raglan encourages his patients to “go all the way through to the end” of their anger, which for Nola, includes manifesting feisty, murderous offspring. Although in my opinion, The Brood dials it back a bit on the gore compared to his first two features, the third act is batshit crazy and it includes a dramatic conclusion for Nola that the director himself admitted to being “very satisfying” to film.

The Brood deals with emotional wounds and fears countless have sustained.

Enduring a traumatic breakup or separation from a loved one is fucking painful, and the performances from each actor in the film earn genuine empathy from myself. There is a scene between Art and his mother in law, where she says, “Thirty seconds after you’re born, you have a past. And sixty seconds after that, you start to lie to yourself about it.” She says this so somberly as she sips on her alcoholic beverage, seeming to remember events that were unpleasant for herself, for her own daughter, for her own ex husband. That particular scene, those words, have stayed with me all these years.

THE BROOD explores the themes of grief, frustration, manipulation, weakness, and the way these feelings can control our actions, often causing us to repeat destructive behaviors, creating this lineage of drama and of hate. He literally put all of his personal fears and anguishes up on the screen for everyone to see and I just think that was so brave, and to this day it deeply moves me.

In an interview on Tonight with Jonathan Ross shortly before Naked Lunch, another feature from Cronenberg was due to release, the director commented on seeming to be well adjusted and normal. “I think it’s true” David laughs then continues “it has something possibly to do with the balance that you try to find in your life and so you just kind of try to put that stuff on the screen so it’ll stay out of your life, and I think that’s part of the process.”

9. THEY LIVE (1988)

Recommended by Todd Reed

Sometimes movies have deeper meanings, and sometimes they don’t…and sometimes people put a meaning into a movie that the creators never intended.

Coming out in 1988, John Carpenter’s They Live was a not-so-subtle attack on the President Ronald Reagan and the rampant consumerism of the Me Generation. What could have ended being a by-the-numbers low-budget sci-fi film is elevated by a premise that holds up surprisingly well more than forty years later.

WWF wrestler Rowdy Roddy Piper plays Nada, a drifter who, after finding a box of sunglasses, discovers that the general populace is being controlled by the elite who use the media to manipulate them into capitulation and accepting the status quo. Oh, and the sunglasses reveal the elite controllers to be an alien race. Nada joins the fight trying to wake people up to what is going on around them by bringing down the transmitter that allows the aliens so much control.

Carpenter seems to have glimpsed the future in the making of They Live. Despite its attack on the 80s, it seems much more relevant to today as more and more people seem to be checking out behind their screens, and we spend more time interacting with stuff we purchase online than with the people in our own homes. The movie even features flying surveillance cameras that are eerily reminiscent of modern drones.

Of course, despite its intended meaning, white supremacists, neo-Nazis, the alt-right (you know, douchebags) have claimed the movie is, in fact, a subversive way to show how Jewish people are controlling the world. The message has gotten prominent enough that Carpenter finally felt the need to address it by tweeting “THEY LIVE is about yuppies and unrestrained capitalism. It has nothing to do with Jewish control of the world, which is slander and a lie.”

They Live is a powerful look at what can happen when we, as a society, acquiesce our freedoms to those who would abuse it and use it against us. Of all of Carpenter’s films, there is probably none for ripe for a modern day remake than They Live.

10. BEYOND THE BLACK RAINBOW (1988)

Recommended by Joe Quinones

Beyond the Black Rainbow is a little known feature from Magnet releasing that can best be described as a slow-burning amalgam of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the seminal video game series “Portal”, sprinkled throughout with heavy David Lynch-ian undertones and all distilled into a tab of acid. It weaves a complex web set in an alternate dystopian Reagan-era version of 1983. Dr. Barry Nyle runs a gamut of MK-Ultra-esque mind experiments on his progeny; Elena in order to control her, and as a result, create a subservient subject.

Allegories are abound in this film as themes of Science, Psychology, sedation, religion, mental health, the MK Ultra experiments, isolation, and the inception of television as a means to control the population run rampant.

We see this macabre perversion of the 80s through the eyes of the aforementioned Elena, who has been born into a life of isolation and experimentation via means that I will not dare to spoil. What comes thereafter is a tale of masochism in the pursuit of science of which, in my opinion, does not get showcased as accurately as it should be in terms of horror cinema — think Hellraiser meets Pavlov.

This film is a cult classic through and through. From the pulsing synth soundtrack to the use of ambient lighting to tell this abstract and surreal tale. This is a classic telling of the notion that the monsters that we should be weary of are the ones that have a pulse and a brain. Using the guise of a retro aesthetic, it reminds us of the inherent horrors of science; whether it be the use of psychedelics to control the human brain, or the dawn of the information age. Science is beautiful and terrifying all at once.

The best allegorical horror forces us to take an introspective deep dive into our psyche and holds us there, sometimes uncomfortably. Beyond the Black Rainbow does that in spades. With its retro yet contemporary tones, atmosphere, and spectacular soundtrack, it makes us look back at an ill-begotten time where the science behind psychology was a fledgling endeavor. One where eggs were broken in order to make omelets, psychedelics were used to tap unforeseen potential, and the human brain was as mysterious and complex as the stars above. It implements those notions to such a high regard and shakes you to your core with it, leaving you reeling with thoughts of how we got here.

BONUS: POSSUM (2018)

Recommended by Danielle De Velasco

Trauma. In all its gruesome forms, there is one consistent truth; we cannot escape its effects. And it isn’t until we face the demon that we can free ourselves of its debilitating stranglehold on our lives.

However, facing all that horror, all that ugliness is so hard, that most of us keep it hidden. We try to forget it or push it down. It controls us and dictates our decisions. But always, like that stalker in the night, it seems like the faster we run, the stronger it gets. We bury it only for it to come back in more nightmarish forms, rearing its ugly head everywhere we turn.

Writer and director Matthew Holness (creator and star of Garth Marenghi’s Dark Place) manages to explore these somber themes in his first feature length film, Possum.

Possum tells the deeply disturbing story of Philip, a puppeteer that is forced to return home to deal with his past and the malicious presence of a repugnant uncle. Philip is also in possession of a monstrous puppet he calls Possum, that he hides in a brown leather bag. He tries to dispose of it, but it always ends up back in his room the next day. When a local child goes missing, Philip suspects Possum is the culprit. But is he?

Based on Holness’ own short story featured in The New Uncanny: Tales of Unease, Possum is a claustrophobic tale of the most significant kind of terror.

The film is beautifully shot, saturated in drab earth tones, the whole atmosphere undeniably grim. A skillfully utilized score by The Radiophonic Workshop adds to the mounting sense of dread. Philip’s chiildhood home is not only bleak and dingy, but seems frozen in time four decades ago. This seems a deliberate move to illustrate how Philip is also frozen in his past; indeed, he is frail and child-like, lost and haunted.

His uncle, Maurice, depicted by a savage Alun Armstrong, is a greasy, unkempt, and churlish man. His menacing grin shows off an array of yellow teeth, as he seems to cruelly chide the awkward Philip, who struggles to maintain his fragile dignity. Sean Harris gives a powerful performance as Philip, his expressions seething guilt and self loathing. With every breath taken, and every word spoken, Harris manages to convey Philip’s inner torture.

Holness takes us through a landscape in which we aren’t entirely sure what is real and what is not. What we are sure of, however, is that whatever resides in that bag is something truly horrific. The puppet is revealed to us in due time, and it’s impressively ghoulish. ( I don’t want to give too much away, but trust me, this puppet is pure nightmare fuel.)

Though we as the viewers are not exactly sure what it is that Philip is holding onto, or hiding, we can see, plainly, that the puppet itself is carried around like literal emotional baggage. Philip is being controlled by a past too terrifying to face, just as a puppet is controlled by strings. Philip tries to dispose of the monstrosity in several different ways, including throwing it into water, burning it, or simply trying to dump it in an array of locations. But is always unsuccessful. The grotesque creation is always popping back up in his room the next morning.

Holness drops clever hints and subtly leads our minds in directions we’d rather not go; the character of Philip is so fragile and sympathetic, and we undoubtedly feel for him. On the other hand, there are signs everywhere that something is very wrong; in the front hall of the bleak house, a child’s old book bag and a jump rope hang in the hallway. There are dream-like sequences that feature the spindly -legged Possum stalking Philip, scuttling just out of sight. People stare and whisper about Philip, as he wanders aimlessly with his bag, smoking cigarettes on the swing set of a playground and staring blankly at school buildings.

Is Philip responsible for the missing child? Are dueling personalities at work here? Is Possum a manifestation of the truth about himself that he cannot face? Saying more would give away the film’s twist.

The beauty of this film lies in its ominous tone and its use of a monster to convey the impact of devastating psychological scars. It successfully creates an environment of sheer terror and mounting paranoia without relying on any jump scares or typical tropes. It’s a slow burn for sure, but one filled with plenty of serious scares along the way.

All in all, Possum is a triumph in modern horror, and an impressive character study of the traumas in our past we attempt to run away from.

1 Comment

1 Record