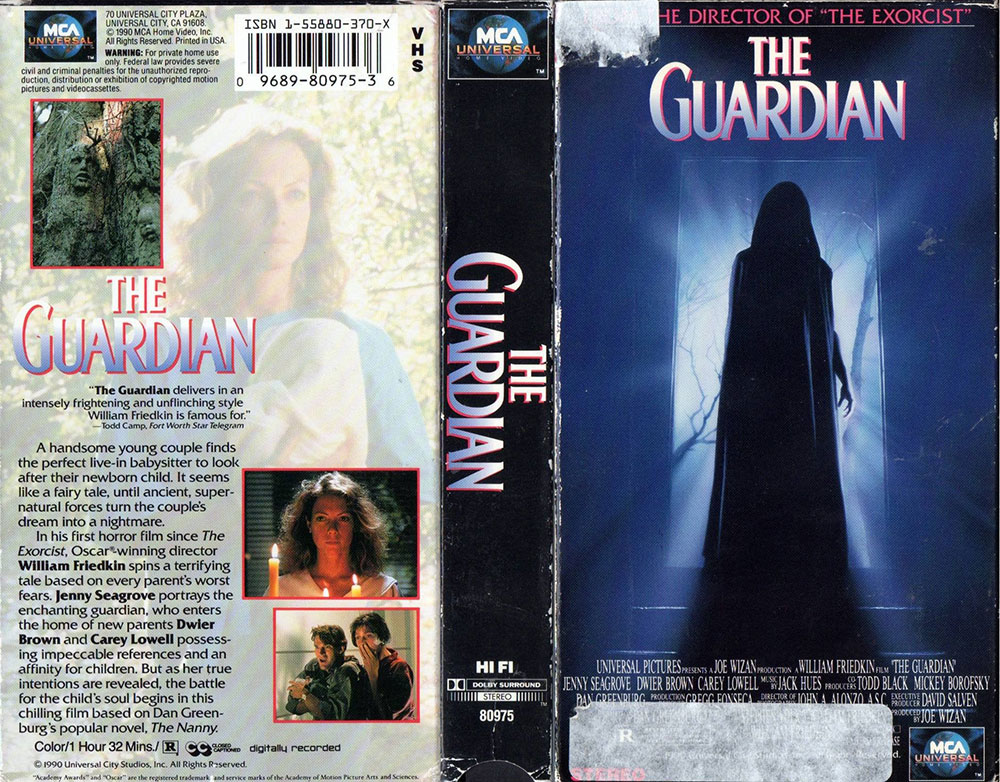

Video Rewind is a look back at forgotten VHS favorites from the video store era, one rental at a time! This month’s movie is “The Guardian” from 1990.

While visiting England and looking to hire a full-time nanny for their newborn son, a married couple became smitten with a young woman looking for work. The young woman was represented by the same agency that represented Princess Diana while she was still a nanny, a connection the married couple was very impressed with. The young nanny said she had never left England, hadn’t even been to London, when the married couple decided to bring her back to the United States with them.

After only two days in the married couples’ home in Los Angeles, the young nanny made a friend. The nanny and her new friend took the baby to a local bar to meet up with a couple of guys, ending the night back at the married couples’ home for some after hours activities, all with the baby present. The following day, the young nanny was very upset because the men had ripped off the two girls and split, taking all of their money along with the new nanny’s passport. Thankfully, the baby went unharmed.

Needless to say, when the married couple found out what happened, the nanny was history.

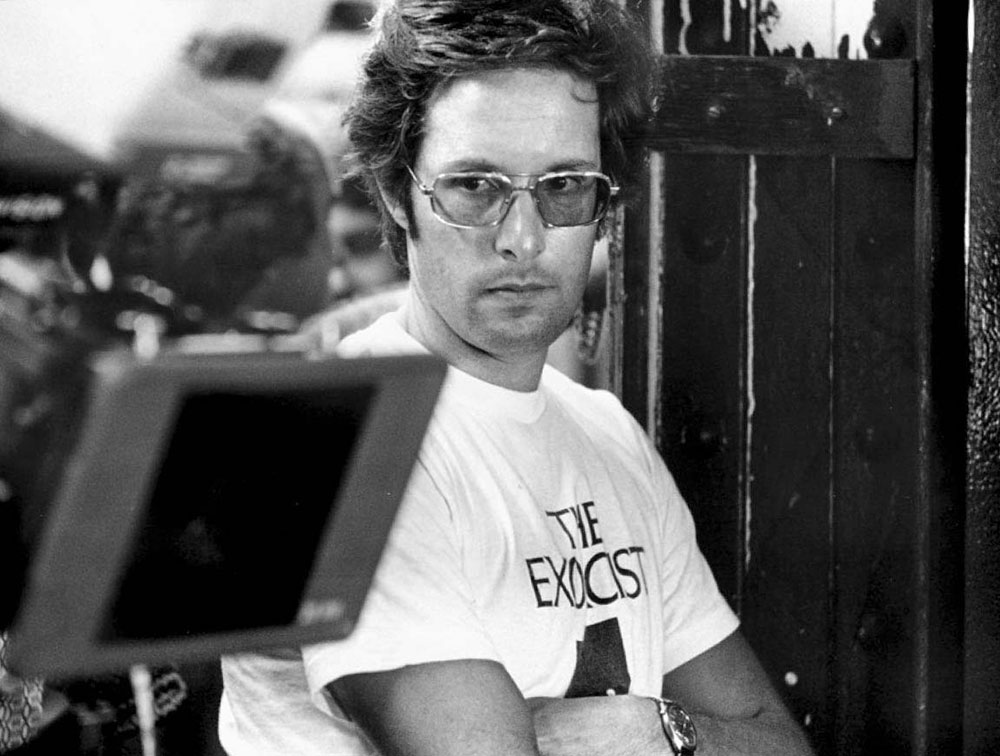

That married couple in this real life horror story was filmmaker William Friedkin and his then wife Lesley-Anne Down (the two divorced in 1985).

Friedkin’s personal nanny-from-hell experience forged his interest in The Guardian, his 1990 horror film based on the novel The Nanny by Dan Greenburg (Friedkin didn’t like The Nanny title).

Sam Raimi of The Evil Dead fame was originally set to direct the film but dropped out early to film Darkman instead. The original script was then given to Friedkin by Joe Wizan, a producer on The Guardian and one of Friedkin’s first agents when he moved to California in 1965. Friedkin found the script to be “lame” but wanted to help out his former agent and friend who he claimed to be “very relevant” to his career.

So Friedkin met with Stephen Volk, the original script writer for The Nanny, and after several drafts together it was apparent the two writers wanted to take the story in very different directions (Volk allegedly suffered a nervous breakdown from all the rewrites). Volk’s drafts stayed closer to the source material, and Friedkin veered into the supernatural at the urging of Universal, the studio looking to capitalize from the filmmaker’s reputation from 1973’s The Exorcist.

This ultimately led to Friedkin writing the final draft of the script himself, even though he never read the novel on which the first draft was based.

Friedkin didn’t set out to make a horror movie when he signed on to direct The Guardian.

He instead viewed the story as a Grimm fairy tale in the classic dark sense, but he wanted it to take place in the modern world.

The story centers on yuppie couple Phil (Dwier Brown) and Kate (Carey Lowell) who move to Los Angeles where Phil lands a job at a lucrative advertising firm, making the contemporary setting as contemporary as it gets for late 1980’s audiences. Friedkin may not have intended to make a horror film out of The Guardian but a horror film is what he made — his first in 17 years, when The Exorcist broke records and was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, earning Friedkin a Best Director nod.

Coincidentally, The Guardian would be released the same year as The Exorcist III, with the latter winning the box office battle (although both were flops).

Dwier Brown, who previously worked with Friedkin on 1985’s To Live and Die in L.A., and Carey Lowell were cast as married couple Phil and Kate. The two actors were both just coming off their biggest films to date in 1989, Brown in Field of Dreams opposite Kevin Costner and Lowell (a former Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren model) alongside Timothy Dalton as Bond Girl Pam Bouvier in License to Kill.

The two would play parents who hire an evil nanny named Camilla to watch their newborn baby while they tend to their blossoming careers.

For the all important Camilla, Friedkin cast Jenny Seagrove, an accomplished British stage and screen actress.

This strong background in the theater reinforced her ability to incorporate a distinct personality in her movements. Camilla moves with a misleading properness, an attribute supported by her calmly intelligent accent. But look closer and her movements seem too stiff, almost otherworldly, as if an entity had learned the movements of high society people and tried to mimic them. Distracting from this is her alluring confidence and beauty and the inherent trustworthiness that naturally follows those qualities.

All of this wasn’t lost on director Friedkin, who once considered Uma Thurman for the role but instinctively cast the talented Seagrove as Camilla saying she had “a mysterious element behind a very charming facade.”

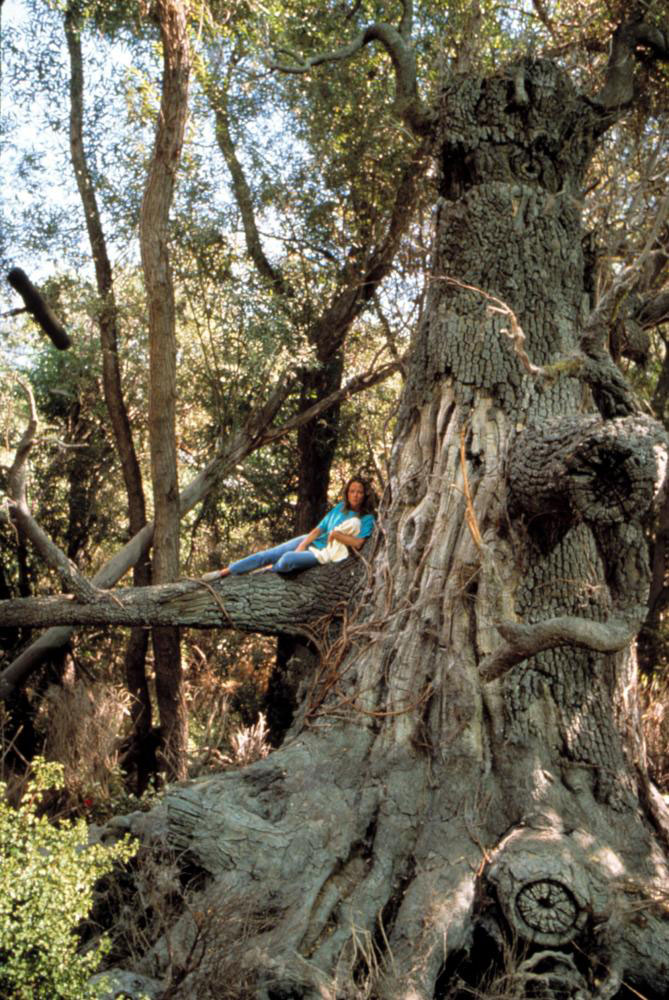

When the three-month film shoot began in June of 1989 in Los Angeles and Santa Clarita, California, the rewrites of the script weren’t finished. Jenny Seagrove said, “pages were flying at us,” and while visiting Friedkin at his home she says the director told her about the Druid mythology he had been reading about and wanted to work it into the film.

“Suddenly this idea of this weird kind of tree came about, and suddenly my character was not just a nanny but she was a Druid character who turned into a part of the tree, and she had to feed the tree — things were evolving all the time,” says Seagrove.

As if an evil nanny weren’t scary enough for young new parents Phil and Kate, they now had to contend with an evil Druid witch who sacrifices babies to an ancient, magical tree in the forest. At least Friedkin didn’t have that to worry about with his nanny.

Just as Friedkin didn’t intend to make The Guardian a horror film, the new direction of the script was not the film that Seagrove wanted to make.

In a 2007 interview with The Guardian (the UK newspaper), Seagrove said, “I begged Universal to make it about a real nanny who kidnaps babies. ‘No, no, we can’t do that,’ they said, ‘the thirty-somethings in America won’t come and see the film.’ I said, ‘I think you’re completely wrong, this film is total fantasy, and it’s just awful.”

The actress goes on to point out that thirty-somethings in America did come out two years later in 1992 to see The Hand That Rocks the Cradle to the tune of $88 million at the box office, a film about a nanny with plans to kidnap a baby. And actress Rebecca De Mornay didn’t have to be a Druid witch or anything in that one.

With the additions of the evil tree and the Druid witch to the story, the budget needed for special effects naturally rose exponentially. Time for makeup application was needed to transform Seagrove into the witch that was one with the tree, making her character in the film appear earthy and covered in bark for some scenes. The construction of the ancient tree caused numerous headaches as the first tree didn’t function properly, causing the first effects team to be fired.

When a second crew was brought on board, the addition of supernatural elements to the large, imposing tree prop had the special effects crew scrambling to keep up. These rewrites dictated the adding of more functionality to the excessive prop, such as inner tubes filled with hundreds of gallons of fake blood so the tree could bleed as well as adding detachable bark. The tree then had to be transported from Burbank, California, to a nature preserve in Valencia, where filming of the forest scenes took place.

Many of these effects were in camera effects and couldn’t just be added on later during post-production, adding tremendous strain on an already strained production.

On top of the growing unhappiness of star Jenny Seagrove and the pressure put on the effects crew with the ever changing rewrites, other members of the production were beginning to feel the stress of working with director William Friedkin.

According to Dwier Brown, while filming a scene where Carey Lowell is cautiously walking around her home after hearing a sound, Friedkin actually hid behind a canvassed wall and fired a blank without the actress knowing to get the frightened reaction from her he was looking for.

Brown found the tactic to be excessive to say the least, and this story fits with the rogue directing style that Linda Blair said she experienced while filming The Exorcist, a get-the-shot-at-any-cost approach that disregards the actors in a way that may put them in danger.

As post-production began, it was time to see if Friedkin could make a respectable film out of the messy production.

In the film, new parents Phil and Kate rent a house surrounded by trees and foliage, the branches practically reaching towards every window and the shadows thrown on the walls inside the house by the moonlight at night. What’s more, Kate actually paints a tree mural on the wall right behind her newborn baby’s crib in the nursery. The tree imagery and foreshadowing isn’t subtle and suffocate almost every scene with nudging bluntness.

But with a story about an ancient Druid witch who sacrifices babies to the spirits of trees, it’s fair to say that subtlety can take a backseat to the more on-the-nose approach of a fairy tale, and that’s exactly what William Friedkin was going for with The Guardian.

Equally blunt is the blood and gore. When some thugs approach Camilla in the park, a branch smashes the head of a hoodlum with blood splashing results. Another gets ripped in half as branches ensnare his body, while still another gets a sharp tree root burst through his chest like a giant spike, all with blood and insides spilling out of the bodies. To top off the brutal scene, a couple of snarling wolves find dinner in the decapitated baddie, gnawing and chomping at the exposed and ripped flesh of his neck.

Perhaps a by-product of a heavily rewritten and edited film by a studio who sensed a disaster, The Guardian attempts to exploit the senses whenever it can.

The film tries to make the most of its 92-minute run time, including multiple nude scenes of the alluring Druid tree witch herself, actress Jenny Seagrove. One such shot finds her naked body laying on the large branches of the old, large tree to heal a stab wound from the hoodlums in the park, her skin slowly blending with the bark as she becomes one with the tree. She’s found this way by a lovelorn character named Ned (Brad Hall) who secretly follows her, at first playfully and then more curiously as Camilla goes deeper into the woods. When Ned is spotted by Camilla’s wolves, it doesn’t end well for him.

Phil gets a phone call from a woman named Molly, a woman from the beginning of the film who had her baby stolen by a mysterious woman named Diana. When Phil meets with her, Molly warns him about Camilla, saying she is Diana and that his child is in trouble. Phil finds this hard to believe. But when he spots a Hansel and Gretel pop-up book, he realizes it’s the same book he saw in a dream he had.

Dreams are a device used often in the first half of The Guardian to set up later events, namely the identifying of who Camilla actually is. While dreams are often viewed as a rather lazy means to an end, they do fit in with the dark fairy tale, image-heavy approach the film relies on (the slow, upright flying of Camilla through the darkened and misty woods towards the end of the film is a standout sequence).

The big finale finds Phil taking it upon himself to destroy the witch by attacking the tree she sacrifices to.

This sequence brings plenty of more squirting blood (those inner tubes in the tree at work), as Phil looks like Ash from The Evil Dead covered in blood and swinging his chainsaw maniacally at the tree. It’s nteresting that Sam Raimi was once attached to direct, because this scene is truly Raimi 101.

Meanwhile, back at the home, Seagrove shines as the earthy and mud-skinned Camilla — with her slicked back hair and wide, unblinking eyes. She makes one final attempt to steal Phil and Kate’s baby. Her movements and stare are chilling as she crashes through doors in relentless pursuit of the child being so tightly held onto by the running and panicking Kate.

It’s a bloody and exciting ending to a film that oddly mixes fairy tales, soap opera-like melodrama, and supernatural horror.

While attending the premiere of the film, Jenny Seagrove recalls, “There was a feeling in the room that it wasn’t the sort of picture everyone had hoped it was going to be.”

Disappointment surrounded Friedkin’s “return to horror”.

When released in theaters on April 27, 1990, The Guardian opened in third place with just $5.6 million (barely enough to edge past Kid n’ Play’s House Party in it’s eighth week of release). It was not received well by critics or audiences, and it fizzled out after only a $17 million box office take. Time Out wrote in their review that The Guardian was “a severely flawed but not unamusing venture from a director who should know better.”

But this statement seems unfair to Friedkin, who attempted to make a rather wild and spectacularly unique film. Things just got out of hand during production. According to Friedkin, the filmmaker judges the success of his films by how close he comes to his original vision.

“The two films where I came extremely close were To Live and Die in L.A. and Sorcerer.”

When asked which film was the farthest from his original vision, he answers, “The Guardian. I don’t think [it] works.”

It’s impossible to know whether the film could have been great.

But it’s clear to see there was never a clear vision for The Guardian, and it suffered greatly during production — so much so that Roger Ebert named it one of his most hated films of all time. But the legendary film critic joked with then reviewing partner Gene Siskel on their TV show that, “There’s one area where this movie breaks important new ground. This is the first horror movie in which a chainsaw is used against a tree.”

The Guardian was released 6 months later on VHS in October of 1990, just in time to make a quick buck in rentals and home video purchases from the Halloween crowd looking for some scary movies to watch. The film was quickly forgotten but has since gained somewhat of a cult following over the decades, even having a Shout! Factory Blu-ray release in 2016 with new interviews and commentary from Friedkin.

Perhaps his involvement with the Blu-ray demonstrates a slight warming up to the film from Friedkin who, along with just one other film, ignored The Guardian completely in his 2013 memoir “The Friedkin Connection”.

There’s no beating around the bush: The Guardian isn’t a great film.

It’s ridiculous on its face and muddled in its execution, with nothing but a simple pre-title prologue as the attempt to explain the Druid witch, tree-sacrificing element of the story (pretty much the whole story).

But this simplicity combined with the wacky sounding story is exactly where the enjoyment stems from.

It’s an audacious and bold film with no fat that moves fast through heightened hysterics and melodrama storytelling. In other words, just like the Druid witch herself Jenny Seagrove said, “I don’t want to put off anyone from watching it because it is good fun.” And she was right. The Guardian is good old fashion trashy cinema that reminds us it’s important to see the forest through the trees.

After all, it’s more fun to be surprised by which tree is the one you’ll be sacrificed to.

Follow Us!