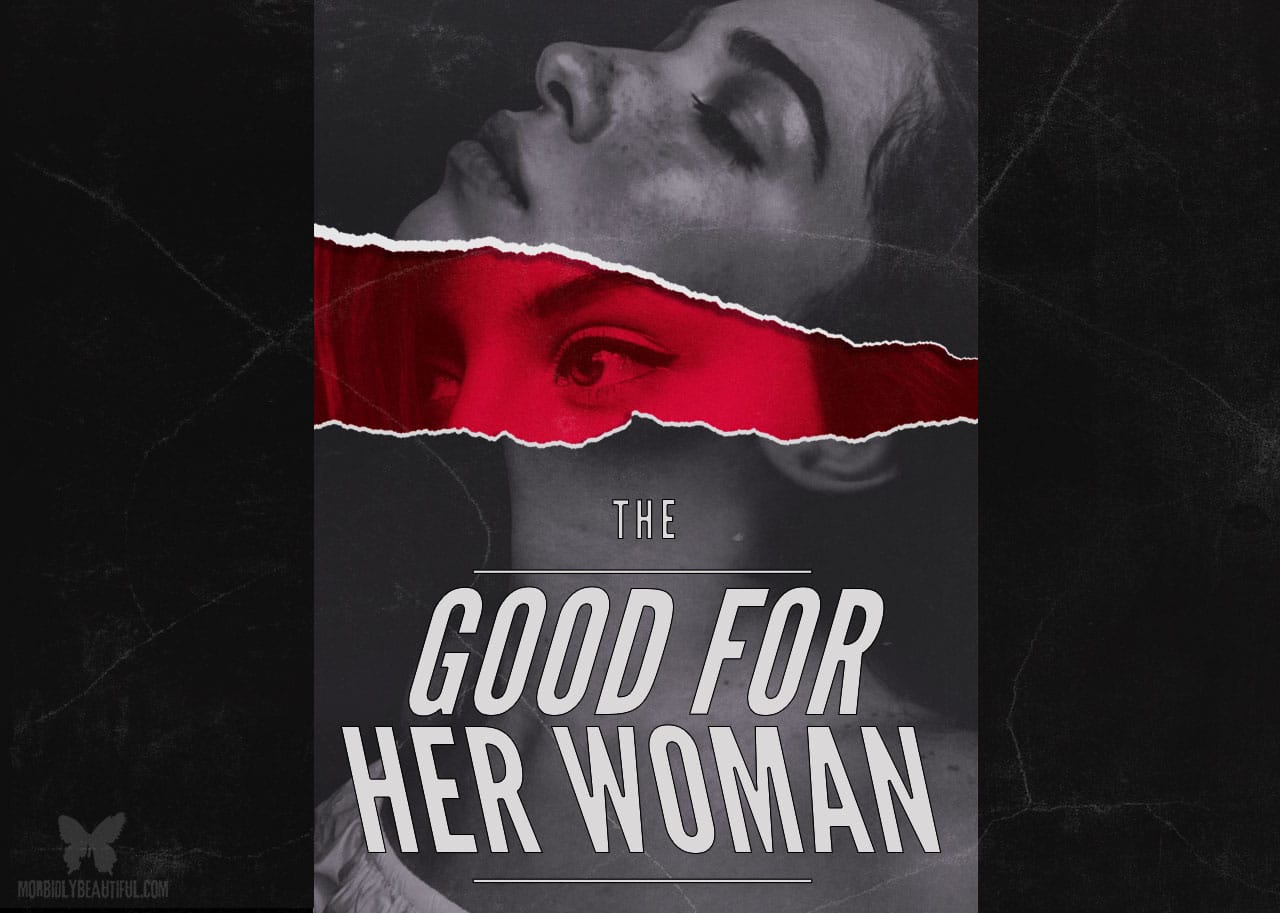

We root for the ‘Good For Her’ woman no matter what she does. She’s just like other girls — but only the other girls we aspire to be like.

Girl loves boy. Boy betrays the girl in a terrible manner that leaves her for dead, or at best terribly hurt. Girl decides enough is enough and makes sure he rots in prison, murders him and stages it as suicide, or stuffs him into a dead bear and lights him on fire. She is probably emotionally scarred and traumatized. And she will likely never again be her old self.

Yet, the story ends as she smiles and rides off to Mexico, makes a pact with Satan (and smiles), or inherits a great fortune with a great curse attached to it (and smiles).

The story is as old as… well, at least as old as 2014. That year’s Gone Girl is widely considered the first clear example of this genre: the ‘Good For Her’ movie. Who is the ‘Good For Her’ woman? What class does she belong to? What is her race, her body type, her appearance? And does our aesthetic perception of a female character influence whether a film is considered a ‘Good For Her’ picture?

Perhaps it is misleading to call Good For Her a genre.

Rather than being a kind of a film that is created with the intention of being Good For Her (though that also can happen), a film is often ascribed the title retroactively. Moreover, it seems that Good For Her can come from all kinds of genres, with Letterboxed offering up films such as Eyes Without a Face and Carrie as key examples, but also including works such as The Watermelon Woman and films by Studio Ghibli.

With such a broad spectrum, what are the definitive characteristics that define a Good For Her film? And what makes it different from the rather tired Strong And Independent Woman trope?

To start with, a Strong and Independent Woman is a sexy, mysterious femme fatale who might dress in skimpy or tight clothes for the enjoyment of a male audience. But she still has some strange plot reason that justifies such portrayal of the female body — with the best example of that being Halle Berry in Catwoman.

A Good For Her woman is not sexy.

She can be sexual, and given that she is usually played by Hollywood actresses, she often is beautiful.

What she lacks is the framing that makes her a sexual object, or to put it simply, she is usually not framed by the male gaze. She is on the screen for the female audience first and foremost. She can even be barely dressed for most of the film’s runtime, but the way her body is portrayed makes it simply nude rather than sexual.

She is not strong, in a physical sense: she is not Ripley expertly operating a flame thrower, rather Jennifer in Revenge who flies onto the ground from shooting a rifle for the first time.

She is, in short, not very exceptional.

She can be a trophy wife in Swallow or Ready or Not, a girl in mourning and depression in Midsommar, or a migrant lower-class worker in Knives Out.

Where a Strong And Independent Woman is supposed to be exceptional — excelling at what a woman can do by being a badass in a very masculine-coded way (with physical prowess being the most noticeable of those traits) — a Good For Her woman is ordinary. She can be any one of us, and her struggle is usually one that many of us experience.

She is a sexual assault survivor, a girl in an abusive or shitty relationship. At most outlandish, she is an android or a clone, but one that struggles with all too familiar class, race, or gender discrimination. A Strong And Independent Woman is essentially a male character in all aspects but her sex, but a Good For Her character is feminine and relatable for a female viewer. Her life is one that most female viewers can relate to, as they faced the same hardships. Only her ultimate triumph remains aspirational.

It is a moment a viewer wishes to have: finding community, finally landing a rapist in jail, punishing a cheating husband.

That victory can be achieved by almost any means.

Many Good For Her characters are morally condemnable: they frame people for murder, sacrifice them in cult rituals, lie, manipulate, kill. Some are downright sociopathic like Amy in Gone Girl, but that does not stop the audiences from relating to them and rooting for them.

The offense that however seems to be unforgivable is going against other women who share their plight.

A Good For Her woman does not build herself up by putting other women down, and her narrative is not one of rising above her gender. She can be cruel and hurtful to other women, but not in the framework of misogyny or oppression. She does not compete over a man or throw shade. She is equal to other women, and they are only worth condemnation if they themselves become secondary oppressors.

When Cassandra arranges things in such a way that Madison thinks she was raped in Promising Young Woman, she does not do it out of malice but as a punishment for Madison not believing a rape survivor. It is a cautionary act: do not go against other women. It will not make you safer and will cause further oppression of your gender.

A Good For Her character is then a sort of extreme social justice warrior who can fulfill the fantasies of revenge and justice the audience has, one that does not present or act in a way that equalizes her with men. She is not supposed to be equal to men, because that would put her in a position of being an oppressor. Instead, she can often be hyper-feminine. Promising Young Woman would be a perfect example here.

While the story follows Cassandra taking revenge on her best friend’s rapists and is brutal in the subject matter, it is portrayed in a beautiful, pastel color palette, with Cassandra dressed in retro dresses and working in a sugary-sweet cafe. The character may look like she is made out of sugar and spice and everything nice, and her environment reflects that, but she cannot indulge in this soft kind of femininity because her life is tainted by the struggle with trauma and gender and sex-based oppression.

A ‘Good For Her’ woman is then truly an everywoman.

Or is she?

While the character can be unlikable or downright dangerously sociopathic and still be a ‘Good For Her’ character, there seem to be certain barriers that keep some fictional women from joining that group.

For example, it would seem that Annie Wilkes from Steven King’s novel and Rob Reiner’s film Misery would fit the trope like a glove. She’s very feminine with her taste for harlequin-style romances and a house filled with ceramic decorations and knick-knacks. When Annie meets her literary idol, she takes matters into her own hands in order to make sure her favorite fictional character gets a happy ending. Of course, she goes about it in a rather unhinged way: by torturing and imprisoning said idol.

That, however, does not sound that far off from how Amy in Gone Girl murders a man only to appear like a victim of kidnapping and rape to gain press sympathy and keep control over her husband.

If Annie does not fit the genre, how about Octavia Spencer’s Sue Ann in Ma? She hurts some teenagers and does in fact control her daughter in what is probably a Munchausen-by-proxy situation, but it all stems from her unhealed trauma of being sexually assaulted as a teenager. She even gets a triumphal moment of revenge against her assaulter in which one can only root for her.

Why is it that Amy’s actions are considered simply collateral damage on her way to a happy ending? Why do we root for Danny joining a human-sacrificing cult in Midsommar and feel good for Adelaide/Red’s freedom at the end of Us. But neither Annie or Sue Ann elicit that same empathy?

The answer could be that we just find characters such as Annie Wilkes simply too unhinged; they go too far.

Relating to such a character would disturb an audience.

But there are other examples of characters who go to extremes and are now heralded as icons of the genre. Elliot Page’s character in Hard Candy tortures and kills sexual predators. The protagonist of Ready or Not is not phased by children exploding in front of her eyes. In fact, Good For Her movies can provide a sort of safe space to explore a viewer’s wishes for over-the-top revenge or justice.

Most people do not wish to kill or frame an abusive boyfriend, but many might find satisfaction in fantasizing about that. A Good For Her film allows indulging in such a wish.

Films such as Ma or Misery then would appear to fit right in.

Is it perhaps a matter of scale? Sue Ann tortures a group of teenagers not because of anything they themselves did, but because she cannot deal with her trauma. Annie Wilkes has even less of a reason — imprisoning and torturing a writer simply because of how a book ends. Those simply do not compare to rape survival.

Still, those characters could potentially bring some sort of catharsis to a female audience.

In a world where female fans are not treated seriously, especially when they love something typically feminine, it might be pleasurable to see a character like Annie Wilkes get what she wants. When what is expected of an older black woman is to be a caretaker for mostly white teens, it may be satisfying to see her turning against them.

Perhaps those stories do not follow the same brutal narrative of a typical Good For Her film, but it would seem they could provide similar feelings of release.

What is different then?

I believe it is a matter of aesthetics.

A Good For Her woman is, as I mentioned earlier, an everywoman — as much as someone played by a strikingly beautiful actress can be. It is only the cruelty, revenge, and anger that the character encapsulates that remains unattainable for a viewer. A viewer is to see herself in a Good For Her woman, thinking she could have what the character has.

Here is the catch though: a viewer is supposed to want to be the everywoman a Good For Her character portrays.

Characters such as Annie Wilkes do not encapsulate aspirational femininity but are rather looked down upon. Annie is not a beautiful, ax-wielding avenger; she is a psycho biddy.

Could it be that we cannot give the grace granted to young, thin, well-put-together (even if they are completely psychotic) characters to those characters whose instability and anger show more on the surface —those who are less representative of traditional beauty standards?

Perhaps what we want to have in a Good For Her character is someone who we do not look down upon but see as the perfect average.

Follow Us!