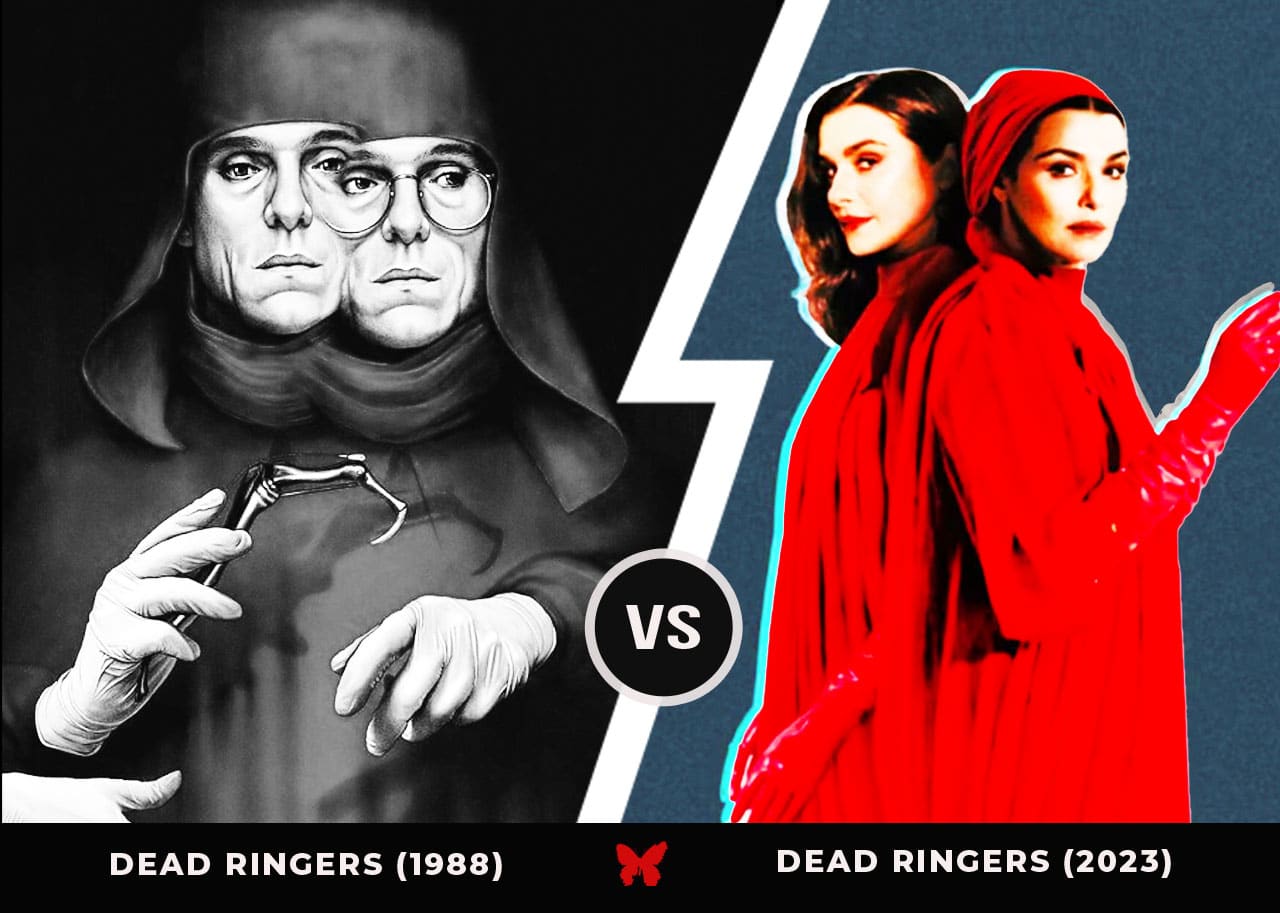

The new series “Dead Ringers” takes Cronenberg’s weird and masterful vision further by giving it a feminist take and adding more rich layers.

Inspired by an unbelievable real-life story of identical twin gynecologists who died from barbiturate withdrawal, Dead Ringers is widely considered to reside among the upper echelon of David Cronenberg’s impressive body of work. The film explores themes of eroticism, narcissism, misogyny, and masculine-feminine dichotomies. It also asks disturbing questions about the nature of individual identity. It features a career-defining performance from Jeremy Irons.

An ambitious project to tackle for a modern reimagining, the new series on Prime Video does just that, giving viewers a gender-swapped remake of Cronenberg’s psychological thriller. The original film was about male control, but the 2023 series amplifies the theme of women retaking control over their own bodies. It also explores what it means to be a mother and to control childbirth, to be fully yourself, and to sacrifice pieces of yourself.

We explore the similarities and differences between the 1988 original and the 2023 remake and discuss how well the series adapts the original ideas of the film and expounds upon them in new and interesting ways.

Dead Ringers (1988)

Written and directed by David Cronenberg (co-written with Norman Snider), Dead Ringers is a 1988 psychological horror film starring Jeremy Irons in a dual role playing identical twin gynecologists, Elliot and Beverly Mantle. The script was based on the lives of Stewart and Cyril Marcus and on the novel Twins by Bari Wood and Jack Geasland, a “highly fictionalized” version of the real-life story.

In the film, the Mantles operate a highly successful clinical practice in Toronto that specializes in treating fertility problems. Elliot, the more confident and cynical of the two twins, seduces women who come to the clinic. When he gets tired of them, the women are passed on to the shy and passive Beverly while the women remain unaware of the substitution. The relationship between the Mantles is established early to be strangely cold. The insular Beverly and the social butterfly Elliot appear to be focused only on science, interacting with the world emotionlessly and sharing women in a quasi-incestuous way without regard for feelings.

Everything changes when Bev falls deeply in love with Claire (played by the fantastic Geneviève Bujold), leaving Elliot in disbelief. Bev becomes dependent on her in an unhealthy way, becoming selfish in his love for Claire and refusing to share her with Elliot. His obsession leads him to lose his mind and spiral into a dangerous prescription drug addiction. Elliot tries to help, which only pulls him into the same downward spiral as his brother, culminating in tragedy for both siblings.

As far as David Cronenberg goes, this is absolutely not his weirdest film. Naturally, however, there is a nightmarish body horror scene that deals with the lack of division between the two. However, it’s not as much about the body and its various horrors but rather the mind (something Cronenberg’s son, Brandon, brilliantly explores in his own film Possessor about the divisions of the psyche).

The film seems to have been an early influence on Cronenberg’s most recent film, Crimes of the Future (2022), especially in regard to the tool shapes that spring from Beverly’s twisted mind. Besides featuring the main character from Scanners (1981) in a cameo role, Dead Ringers feels like it exists in the same universe as that film.

Dead Ringers (2023)

The show on Prime Video — released 35 years after its predecessor — also follows the Mantle twins; this time, however, the twins are female and played by the excellent Rachel Weisz.

The Mantles are the best at what they do. Beverly dreams of owning her own birthing center to help everyone, while Elliot wants to run her own lab. They seem somewhat normal, though they do switch roles periodically to help each other out. Elliot is clearly the “bad” twin with her unhealthy, manipulative behaviors. At the same time, Beverly embodies the “good” twin, a champion of what is right whose platitudes crumble in the reality that involves money.

Beverly wants a baby, but her body doesn’t support it, and Elliot wants to fix this for her.

Elliot also reels in Genevieve, an actress Beverly desires but doesn’t have the forwardness to pursue. Elliot believes this is simply a fling, but it becomes serious, complicating the codependent dynamic of the twins, especially for Elliot. Elliot spirals due to her perceived abandonment and eventually botches a simple surgery. Beverly is told she needs to sever ties with her sister and abandon her. She complies at first, but she can’t maintain the separation, giving Elliot the chance to sever the ties permanently and assume Beverly’s identity.

With the shocking role reversal and the introduction of new twins, season one concludes, and we’ll have to wait for season two to continue the twisted tale.

The Same but Different

The film and the show share almost the same story with different faces and genders. But women are more complex in their desires and, in my opinion, more interesting. I love that in the show, we see them address the possibility of an incestuous relationship right away, getting it out of the way. People have strange ideas about twins (worse when it comes to female twins). There’s also the misogynistic aspect relating to how men often fantasize about sisters/twins in a sexual context. And I appreciate the way the show subtly addresses that.

We also get an authentic look at the beauty and the trauma of childbirth, along with the human experience of being a woman with all our complexity and contradictions.

The time period is different in the two properties, with the movie taking place in the 80s and the show in the modern day.

The male Mantles work in the area of infertility without ever delivering babies. Contrastingly, the women Mantles address infertility issues but focus primarily on bringing life into the world. I see this as an expansion of the original concept. With this clever gender-swapped version, the story moves from one about male control to one about women taking control over their own bodies. Sadly, this has become quite a timely theme in recent years, making the subject matter resonate in a truly powerful way.

Hospitals, by nature, are transient places of pain. They are filled with suffering and loss. But they are also filled with hope, joy, relief, and new beginnings. This dualism is highlighted in the show but glossed over in the movie.

The character work is a little more substantial with Jeremy Irons’ performance as the male Mantles; I can tell which twin is which just by Irons’ body language and sometimes from a simple glance at his face.

Now, that isn’t to say Rachel Weisz’s performance as the female Mantles isn’t powerful — because it is. But the only difference in appearance between the twins is literally the hairstyle. Elliot is forever acting out with her hair down, while Beverly is forever reserved, polite, and proper in a constant bun. Perhaps in this rendition, they wanted to focus on how no one can tell the twins apart. Here, even the audience isn’t always sure who is who, which does add to the intrigue.

There is a boldness to the series and a willingness to address some elephants in the room that the movie lacked. That’s not to say the film isn’t stellar; it maintains a solid shock factor and tackles some challenging questions.

Genius and talent are often mixed with madness, which the movie and the series both effectively explore.

Homages/Sinister Settings

Homages to the original movie are littered throughout the series if one knows what to look for.

The illustration of the two twins in utero shows up in the early credits of the movie and then in the show as an homage; this image is seen/discarded by Genevieve, who is named after the actress who played Claire in the original movie.

The red uniforms are another holdover from the original; in meaning for both, it seems nefarious, like we’ve stepped into Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, where women are subjugated to bear children.

The birthing center looks like a futuristic spaceship vehicle that careens into the future; the red lights make it seem automatically sinister. We also have a sort of sinister setting going on in the movie as well; it’s a stylized office setting with blacks and reds. In the series, the birthing center is the future, while everything else feels stuck in the past, even pesky issues of legality.

Without Genevieve by her side (since they separate briefly), Beverly reverts to a 70s style with her peasant blouse and yellow hair scarf. This is interesting if you consider that the women’s liberation movement pushed for greater equality (especially in the workplace during that time in history).

Motherly Beverly and pant-suited modern “father” Elliot push forward in their own way to raise the children (who are also twins in utero) together. What a tangled, codependent web they weave because the idea is that they need only each other, dually for themselves but also for the twins Beverly will give birth to.

The things that unhinge the twins in the film are different.

Beverly loves Claire, so he can’t bear her division from him, feeling literally halved. But Elliot can’t bear having division between himself and Beverly. This also trickles from the source material in the show. Elliot can’t bear the separation, though neither can Beverly. It is Beverly who elects to die so Elliot can take her place. Elliot unravels instead of Bev, who is the “weaker” twin in the movie.

Elliott, in both the film and show, doesn’t really know themselves without Bev; they fill the negative space of what Bev isn’t. Without Bev to direct them, they feel lost. There’s real love there, but love can get twisted. They fill the spaces in between so that nothing separates them, seeing themselves inevitably as Siamese twins (the movie says this explicitly while the show does not) that must be separated for the good of both.

Side Characters

Susan is with Rebecca, the twins’ backer in the series for the birthing center. Susan seems sympathetic and sweet, wanting to help women by funding the birthing center. But as we see later, she has her own issues. It’s like a twin convention at her dad’s house in Alabama (and by the way, having your father as your gynecologist is fucking weird). This is some actual incestuous weirdness with the dad using his “practice” to very literally get all up inside his family.

The effect is skin-crawling, and these people see nothing wrong with it — shocker.

Rebecca’s characterization feels like the Devil Herself with how she’s directly responsible for the opioid crisis and cares only about dividends, not people. Her funding effectively catapults the birthing center from an idealized haven for women in general into the territory that only rich white women will ever be able to pay so extravagantly for.

Greta’s arc in the series is much more interesting.

Greta is the Mantles’ maid who is seemingly obsessed with the twins, stealing their trash/hair. Greta is an artist, but the Mantles don’t know anything about her. She isn’t a person to them but a job. Greta then takes what she needs for her art from them to convey how healthcare is a hellhole for everyone else.

The Mantles have little understanding of how the rest of us live without insurance and money to throw at things to make them go away. For Greta, she lives without her mother, who died from shock in childbirth, while the Mantles openly ignore theirs. It shows how out of touch the Mantles are.

Genevieve and Beverly walk by Greta’s gallery show without putting it together that it’s the same Greta they know. Exposed here is the idea that if you aren’t noticed in the right way by the right people, your art can (and does) just fade away along with any message you had.

None of these characters existed in the 1988 movie.

The Real Ghost Stories

Bev wandering through Susan’s Southern-monied childhood home with only a lantern to light her way, as if she’s in her own ghost story, is a very interesting and wholly wasted plot point in season one.

The true ghost story is how black women have been mutilated for the “greater good” of white women, especially during slavery. Gynecology existed for white men to pretend its history isn’t heinous/evil. There’s a lot of subtext that they didn’t develop enough for me. Why bring up something so fascinating if you aren’t going to use it?

The Mantles’ story arc devolves into the problems of rich white people, who are the problem in that they notice nothing outside of themselves, nor do they have any understanding of what life is really like for anyone marginalized.

Silas, a black journalist, is looking in on the Mantle’s lives/center to write a puff piece and notices immediately: this is a prosperous white woman operation because no one else could ever afford it. No matter how rich, there are still things that can’t separate them and their money from people in poverty: infertility, inability to have a baby born alive, etc.

Elliot wants to change that, which is noble in its way, but only for the ones who can pay. This strips away the nobility from the action, especially when we see her cross very illegal eugenics experimentation laws.

It does bring up questions: should we be tampering with nature itself? Is it something to be overcome or something to accept as natural, culminating in the ultimate question: is death even natural?

Something the show really doesn’t address is anyone besides women who have uteruses, which I was disappointed by mainly because of how much trans rights are at the forefront of the political conversation in the U.S. The freedom to exist is literally being stripped away through policy; it isn’t just women who are victimized.

Not only that, but abortion is mentioned only in passing.

As entertaining as the show is, it shies away from tackling the issues or expounding on its own subtext. But, hopefully, there will be a further exploration in the next season of these underutilized but compelling storylines.

Follow Us!