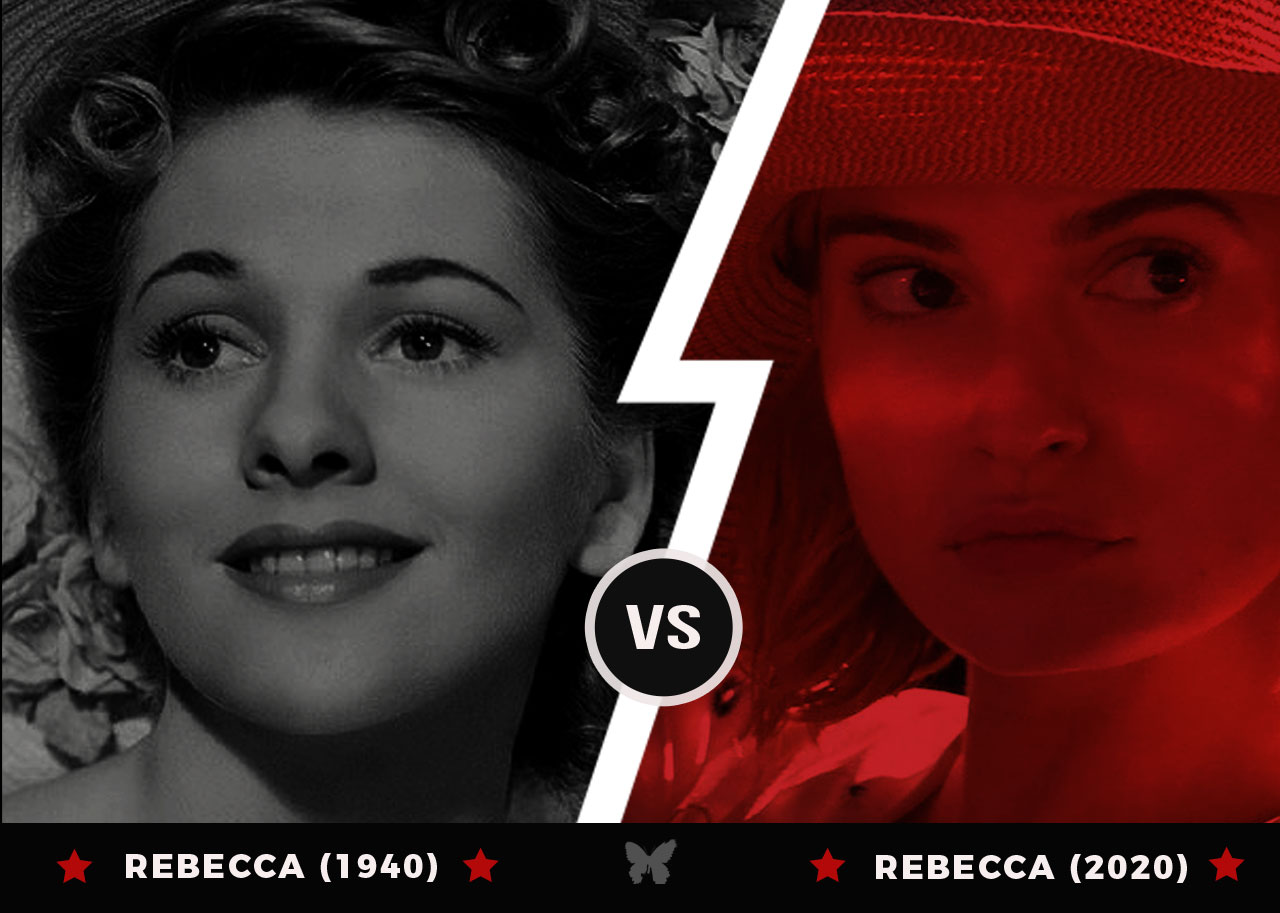

1940’s “Rebecca” from Alfred Hitchcock is widely considered a masterpiece, but how does the 2020 remake stack up to the now 80-year-old adaptation?

Author's NoteWhile the 1938 novel is acknowledged as the source material for both films, this article only compares the films to each other and does not include the novel as part of that analysis.Adapted from the 1938 Daphne du Maurier novel of the same name, Rebecca (1940) marked the first American film production for legendary director Alfred Hitchcock. The story centers around Mrs. de Winter (Joan Fontaine), and her struggles adjusting to her new role as the wife of aristocrat Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier) and the new lady of his estate, Manderley. Mrs. de Winter must contend with Maxim’s ever changing mood, his intimidating housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson), and the lingering presence of his deceased wife, Rebecca. The film would go on to earn 11 Academy Award nominations, winning Best Cinematography and Best Picture.

Revisiting a masterpiece like Rebecca for an updated adaptation could be considered a risky undertaking at best. But filmmaker Ben Wheatley took directing duties on a new adaptation of the 1938 source material, and the new film was recently released on Netflix. Early signs of the 2020 version were promising, with the cast including Lily James in the lead role of Mrs. de Winter, Armie Hammer as her husband Maxim, and Kristin Scott Thomas as Mrs. Danvers.

While Rebecca 2020 won’t see 11 Academy Award nominations (production and set design nominations are real possibilities, however), the latest adaptation, if not as effective as the 1940 version, is a decent and worthwhile film.

It’s fascinating how similar but different the beginnings of each film are.

Wheatley’s version shows how the future Mrs. de Winter is kept in her place more by Mrs. Van Hopper (the always excellent Ann Dowd), the woman who pays for her company. “You’ll meet someone in your own class,” Mrs. Van Hopper says to Mrs. de Winter about the two moving to New York, lacking awareness of her hurtful words. She belittles James’ Mrs. de Winter, shaming her for believing Maxim would actually be interested in her.

James comes across as more naive but curious in the 2020 film, whereas Fontaine in 1940 is more demure and unsure of herself. Hitchcock presents Mrs. de Winter as more aloof, someone who should feel lucky to be where they are in life, even if they aren’t what they want to be. Put another way, Fontaine’s Mrs. de Winter has no right to question or attempt to better herself. Wheatley gives the character a little gumption, a sign of a more modern woman.

James sells this characterization with a strong delivery of a single line: “I can learn,” she says, struggling both not to cry and to convince herself when Mrs. Van Hopper implies she won’t be able to manage the upkeep of Manderley, Maxim’s sprawling estate by the sea. It’s a great early moment for James in what is ultimately a remarkable performance.

The 1940 version has the future Mrs. de Winter meeting Maxim as he stands on the cliffs of the ocean, staring down at the waves below, seemingly contemplating jumping. “No, don’t,” Fontaine yells in alarm. Olivier’s Maxim is surprised and annoyed to be caught in such a compromising moment, quickly acting as if jumping was the furthest thing from his mind. In the new version, the future Mrs. de Winter meets Maxim at the dining room of the hotel while attempting to tip the waiter in order to get Mrs. Van Hopper to sit with Maxim for lunch. Worried she didn’t offer enough, James clumsily drops change on the floor and it’s Maxim who helps her pick it up. The next day, when Mrs. Van Hopper is ill, Maxim insists that the future Mrs. de Winter sit with him.

So, Hitchcock decides to lay the groundwork early for Maxim’s deep troubles, while Wheatley holds them to develop later on. Although vastly different, both meetings play equally well.

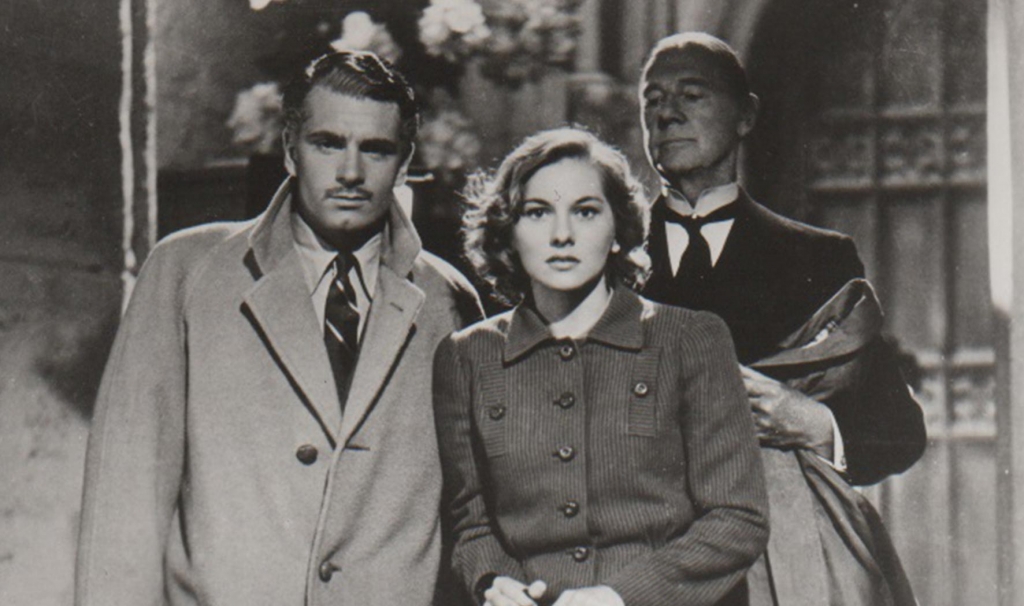

Both films take the time necessary to develop the relationships between characters, specifically that of Mrs. de Winter and Mrs. Danvers.

Joan Fontaine and Judith Anderson in Rebecca (1940)

One major difference between the two adaptations, with a few scenes proving to be exceptions, is that Wheatley doesn’t rely so much on atmosphere like Hitchcock did. Wheatley instead focuses on moments that serve as constant reminders of Rebecca, like finding her hair in one of her brushes as Mrs. de Winter uses it. Wheatley also has a few ambiguous, watery dream sequences from Mrs. de Winter and Maxim sleepwalking at night into Rebecca’s old room, fine moments for the film.

Dreams and sleepwalking aren’t found in Hitchcock’s version, but he does utilize the same type of discovery moments of Rebecca. The 1940 version also plays dramatically with shadows and light, building a persistent, unsettling presence of the deceased Rebecca.

Perhaps this effect is simply a byproduct of the black and white cinematography, but there are a number of moments that make it appear as though a shadow is cast on people in the scene. This technique is mostly in scenes involving Maxim and Mrs. de Winter or Ms. Danvers, giving the impression of Rebecca being in the room. Later in the film, Olivier’s Maxim gives credence to this observation by saying, “her shadow has been between us all the time.”

This layered addition to the film is undeniable, and the extra complexity it adds to numerous scenes towers above even the best moments of Wheatley’s 2020 adaptation.

Another strong, stylistic choice that elevates the 1940 Rebecca above the 2020 version is the use of music.

Hitchcock’s version takes on a spectral quality at times, specifically at the mention of Rebecca. The original spends more time with Mrs. de Winter getting to know the house. These moments are just as vital to the story as the relationship between her and Ms. Danvers as they are really one in the same, both serving as outlets for the overwhelming presence of Rebecca.

One scene in particular shows Fontaine entering Rebecca’s old room, the much ballyhooed west wing where no one goes. Upon entering the room, Fontaine closes the door behind her, and a swirling, hollow wind is added to the music, bringing a ghostly, tomb like sound to the scene. The 2020 score is more subdued and creates a secretive tension, like something boiling just under the surface. It’s an effective score, but Wheatley’s version lacks the ghostly sound that offers the kind of chilling punch like that scene in Hitchcock’s version.

Fontaine is achingly beautiful as Mrs. de Winter. With every close up neither the camera or the viewer wants to leave her face. Fontaine possesses the uncanny ability to become more beautiful the more you look at her, a trait that Lily James shares. Like Geoffrey Macnad observed in a 2013 Independent article about Fontaine, “no one else suffered so glamorously on screen,” and boy does Fontaine suffer. Her performance in Hitchcock’s film is a towering achievement, one that successfully conveys conflicting emotions in every frame. Her efforts rightfully earned her an Academy Award nomination (she’d win a couple years later in another Hitchcock film, Suspicion.)

With these impossible shoes to fill, Lily James gives the role everything she’s got and achieves wonderful results.

Lily James (Rebecca, 2020)

Her performance is a minor miracle the way she successfully updates the melodrama technique of 1940’s cinema for a modern production. James is an absolute revelation in Wheatley’s film, and her tortured Mrs. de Winter is the biggest take away from the 2020 adaptation. Both Fontaine and James have a captivating screen presence that increases the viewer’s concern for Mrs. de Winter as the story progresses, and her situation becomes more uneasy.

Lily James should be especially proud of her performance here.

While Fontaine stole the spotlight from Laurence Olivier in 1940 (he too was Academy Award nominated, however) and Lily James steals it from Armie Hammer in 2020 with their portrayals of Mrs. de Winter, it’s Maxim de Winter that is the more complicated, difficult character.

Maxim is both charming and hot-tempered, caring but distant; his relationship with his deceased wife hanging heavy over him at all times. Olivier demonstrates a deep sadness in his portrayal of Maxim in 1940, a trait that leads to a confident bluntness that at times comes across as snobbish. But the same bluntness fuels a cool charm that allows him to get away with saying virtually anything he pleases, even referring to Mrs. de Winter as “little idiot” more than once. His wounded demeanor and sophisticated good looks serve as an easy distraction to his inner demons, and Olivier walks this complex line with ease in a tightly focused performance.

Armie Hammer has the same self serious, charming disposition as Olivier, and his casting as Maxim de Winter was an inspired choice.

Hammer plays the role with a more angered tone than Olivier, hindering the character’s more mysterious qualities.

Armie Hammer and Lily James (Rebecca, 2020)

The angered approached plays as a miscalculation compared to Olivier, with the character coming across as less haunted, less vulnerable, and less emotionally scarred. Hammer gives a good performance, but the lack of emotional complexity works against the film by diminishing the haunted sensation that Rebecca has left on the house and its inhabitants.

One rather big difference is the scene where Mrs. de Winter accidentally breaks a prized ornament in the office at Manderley. In the original “picturization” of Rebecca (as the 1939 version title cards refer to it as), Fontaine’s Mrs. de Winter admits only to Maxim that it was in fact her who broke the item, not the servant boy who was blamed. In the updated adaptation, James’ Mrs. de Winter admits it to everyone present, including Ms. Danvers, when the boy is accused.

This difference gives James’ version a little more backbone sooner than Fontaine’s. On the other hand, Fontaine has her backbone moment a few scenes later when she instructs Ms. Danvers to discard of all Rebecca’s letters that have been kept in the office. “But these are Mrs. de Winter’s things,” Ms. Danvers says. “I am Mrs. de Winter now,” Fontaine says, in the character’s most confident delivery of the film to that point.

Of course, in both versions, these confident moments are undercut by Ms. Danvers when she encourages Mrs. de Winter to wear the same dress to a costume party displayed in “Maxim’s favorite portrait” hanging in the hall. Unknown to Mrs. de Winter, the portrait is of Rebecca, leaving Mrs. de Winter ridiculed by Maxim and humiliated in front of all at the party. Wheatley’s version adds an effective scene to Mrs. de Winter’s humiliation with James wandering down to the servant’s kitchen in the basement and one servant says, “you don’t belong here, miss.”

But she’s been told her whole life that she in fact does belongs there, down with the lower classes. Back up at the party, she doesn’t fit in there either, uncomfortably making her way through the dancing aristocrats in their expensive costumes.

A surprising disappointment in the 2020 adaptation is Kristin Scott Thomas as Mrs. Danvers.

Rebecca (2020)

Scott Thomas is an exceptional actress, and her performance in Rebecca is solid, perfectly portraying Mrs. Danvers as cold and intimidating. But she never once reaches the utterly chilling presence that Judith Anderson so effortlessly captures in the 1939 version. Once again a performance in Wheatley’s version fails to enhance the eerie, lingering presence of Rebecca the way Hitchcock’s performances were able to in his film.

Scott Thomas’ Mrs. Danvers is cruel to Mrs. de Winter, despising her for assuming Rebecca’s place. Like Hammer, it’s a good performance, but it pales in comparison to the Academy Award nominated Anderson, who works to make Mrs. Danvers seem taken over by the ghost of Rebecca at times, and who gives one of the most frightening stares in film history.

On the other hand, a surprising improvement in the 2020 adaptation is the performance of Sam Riley, who is excellent as Rebecca’s cousin, Jack Favell. Riley presents an intriguing character with his brief screen time, making Favell ultimately more slimy, but also more charming. It’s a more mysterious portrayal than the 1940 version played by George Sanders, who comes across as snobbish from the start. Both portrayals work and serve the story well, but Riley’s performance adds another layer and is an upgrade from the 1940 film.

Like the beginnings, the endings of each film are both similar but different.

After such a serviceable effort to follow up on Hitchcock’s masterpiece, Wheatley’s ending feels plodding and flat as it loses steam during its final act, devolving into an uninspired procedural with courtroom drama. In both versions, with Maxim on the brink of being charged with Rebecca’s murder, Favell attempts to blackmail Maxim.

The original film has the superior ending.

While Sanders’ Favell tries to blackmail Maxim while in the company of him and Mrs. de Winter, Riley’s Favell attempts the blackmail with only Mrs. de Winter present, with Maxim entering the room mid conversation, his temper flaring. This is another little change that makes Riley’s Favell that much more slimy. In Hitchcock’s version, the blackmail scene is smartly combined with others that Wheatley decided to play out separately. Hitchcock quickens the pace of the ending keeping the audience’s attention more effectively.

Wheatley’s 2020 Rebecca is a good film. While some of the performances lack a much needed depth, Lily James shines in the lead role, remarkably on par with the great Joan Fontaine in Hitchcock’s film. The costumes are detailed, the set and production design is absolutely gorgeous, and the film pops with a vibrant color scheme.

However, the legendary Alfred Hitchcock crafted a moody masterpiece of atmosphere with his 1940 REBECCA, and drew complex, Oscar nominated performances from his cast. Both Wheatley and Hitchcock’s REBECCA are worth watching, but it’s Hitch’s film that you’ll be revisiting more than once.

Follow Us!