In honor of its anniversary, we celebrate the legacy of “Nosferatu” and its significant impact on the history of vampire lore in cinema.

Often credited as the first vampire film, Nosferatu (1922) was released in the United States on June 3, 1929.

A clerk travels abroad on a business trip to close a real estate transaction with a foreign count who happens to be a vampire, Count Orlok (Max Schreck). The plot of Bram Stoker’s classic Dracula (1897) is thinly disguised by changing characters’ names and locations.

F.W. Murnau’s classic silent film would become the center of controversy.

Florence Stoker, the widow of Bram Stoker, successfully sued the production company for copyright infringement. As a result, all except one copy of the film was destroyed. Lucky for future horror fans, that one print survived. This print was copied and eventually distributed worldwide.

Nosferatu is more than just a Dracula “knock-off. Murnau takes the basic plot points of Stoker’s story and gives it a unique spin.

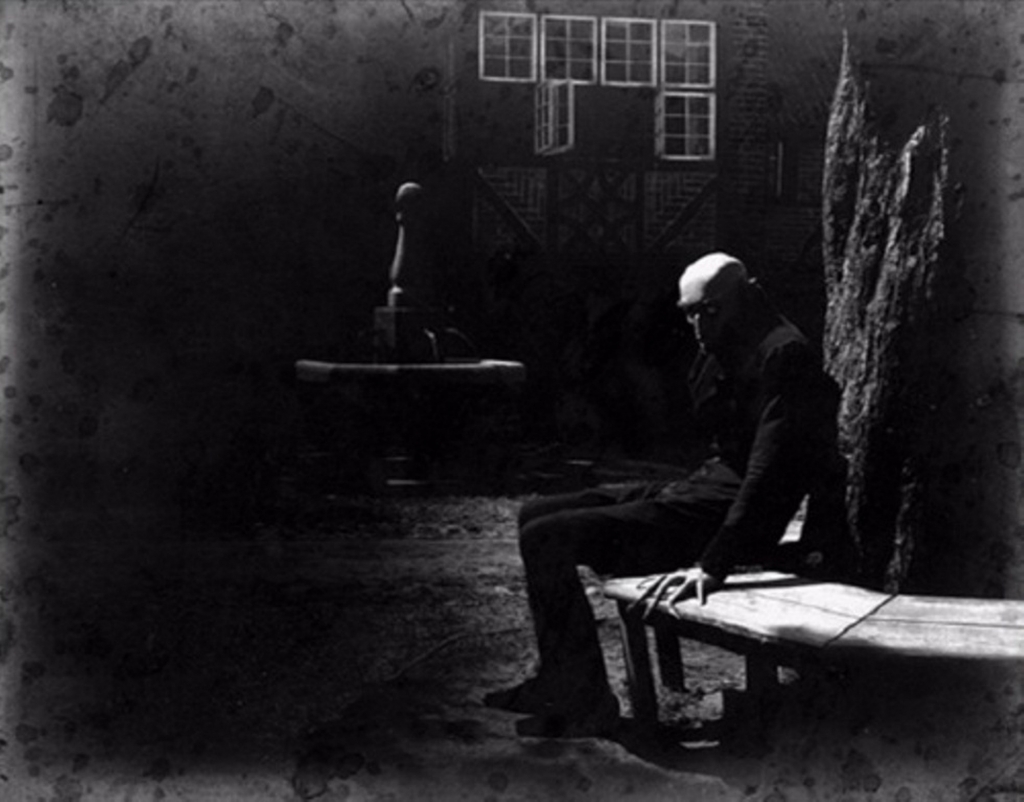

Visually, the film is remarkable — almost dreamlike with the play of light and shadow.

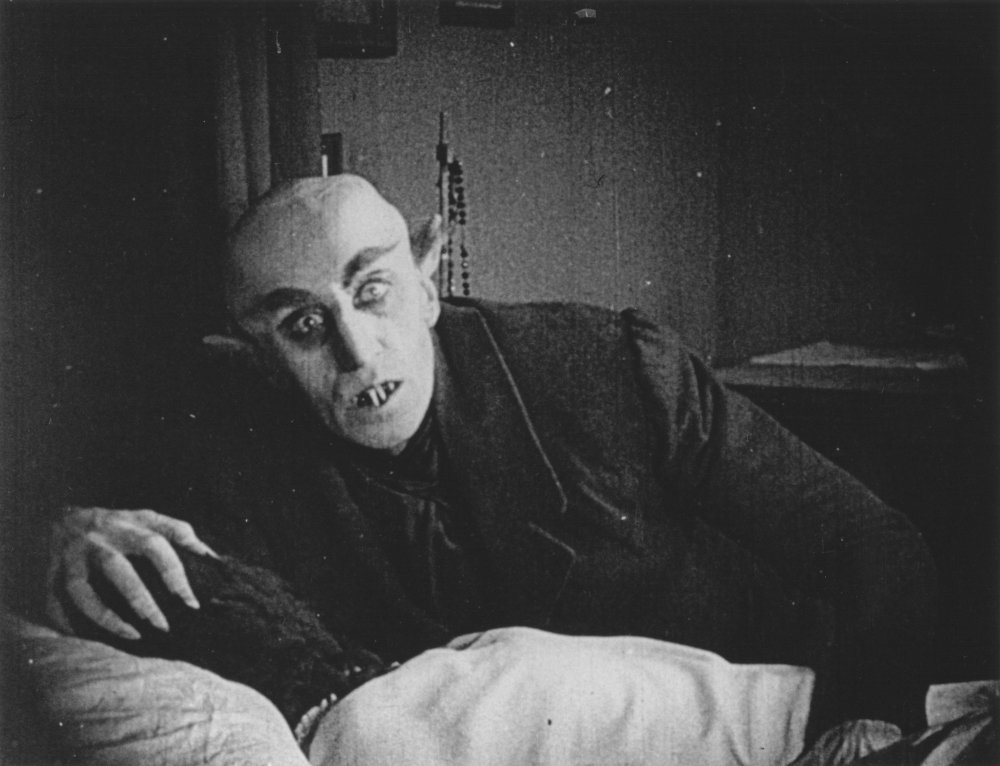

Max Schreck’s makeup is outstanding. Count Orlok has a striking, rat-like appearance with pointed ears and bucked fangs. His hands are more like talons with long, thin fingers topped by sharp nails. Artistically speaking, the film brings a dark nightmarishly chilling landscape of light and shadow to life.

Albin Grau is responsible for making Nosferatu possible.

In 1922, Grau started Prana Film with Enrico Dieckmann. Grau was a World War I veteran. He was stationed in Serbia where local folklore was rich with vampire tales. While in Serbia, the people entertained Grau with supposedly true tales of vampires stalking the populace. Grau recalled meeting a farmer who said that his father had become a vampire.

When Grau decided to establish Prana Film, he had vampires on the brain. He wanted to make a vampire film to be Prana’s first project. He got the idea from his experiences in Serbia, but he needed a story. And Stoker’s Dracula was a popular story at the time.

Grau hired director F.W. Murnau who had distinguished himself with his expressionistic style.

Grau served as designer and art director. He designed costumes, sets, and makeup — including Schreck’s look.

Henrik Galeen wrote the screenplay, but the producers never received approval to adapt Stoker’s novel to film.

According to German copyright law, Dracula was not yet in the public domain. Stoker had been dead for about ten years, but German law specified that an author must be deceased at least 50 years before their work entered the public domain. It would later be discovered that Dracula was, in fact, in the public domain in the U.S. at the time. But as far as Germany was concerned, Dracula was the property of Stoker’s widow, Florence. It isn’t clear whether or not the producers tried to contact her.

The film proceeded as planned with a thinly disguised adaptation of Dracula.

The characters’ names were changed while the basic plot was the same. Count Dracula was changed to Count Orlok, Jonathan Harker became Thomas Hutter, and 19th century England became 17th century Germany. Prana mentioned Bram Stoker not only in the film’s opening credits but also in the promotional materials, which wouldn’t help them later.

When the film was released in Germany, critics loved it but audiences weren’t lining up to see it.

Prana Film spent more money promoting Nosferatu than making it, and Prana went bankrupt.

Florence Stoker wasn’t pleased when she received a flyer in the mail advertising Nosferatu as “Freely adapted from Bram Stoker’s Dracula.” A large portion of her income came from royalties from her husband’s novel. Florence decided to sue Prana Film for copyright infringement. However, Florence’s day in court would be disappointing since Prana Film had gone bankrupt. Florence was determined to get her pound of flesh and wanted copies of the film destroyed.

The court ruled in her favor. German authorities were ordered to find and burn all prints of the film.

Fortunately, one print survived and made it to the U.S. The surviving print was copied and passed along through the years. Nosferatu wasn’t in violation of United States copyright law so American audiences were free to enjoy it. When she heard, Florence Stoker was quite upset.

According to a 2019 article, “How Nosferatu Ripped Off Dracula and Became a Plagiarism Success Story,” writer Michele Debczak says, ” … she continued to round up any copies left floating around and had them set ablaze. She railed against every new screening she heard of but failed to stop the film’s growing cult status. Eventually, she tried a different tactic: If the courts weren’t able to kill Nosferatu, she figured a second vampire film might do the trick.”

Florence readily gave her consent to Universal Studios to make Dracula (1931).

As classic and iconic as Tod Browning’s Dracula is, Murnau’s film has also stood the test of time, carving its place beside Browning’s film in horror history.

About 100 years later, Max Schreck’s ghastly and disturbing Count Orlok has become just as recognizable to horror fans as Lugosi’s otherworldly and elegant Count Dracula.

Nosferatu is a different interpretation of Dracula.

In a 2020 article on northjersey.com, writer Jim Beckerman points out a major difference between Stoker’s novel and Murnau’s film. In his article, titled “This early ‘Dracula’ movie has a message for today,” he explains how the imagery in Nosferatu, specifically the use of rats in the film, symbolizes the plague.

From 1918-1920, a pandemic, referred to as the “Spanish Flu,” claimed the lives of 287,000 Germans and 50 million people globally. He refers to a scene where Count Orlok walks off the ship and rats swarm into the town. This scene resembles those described by historians when talking about times of plague.

Beckerman quotes a description by historian Donovan Fitzpatrick:

“In January of the year 1348 three ships carrying cargoes of spices put in at Genoa, Italy. They were also loaded with rats, lean and hungry, that scurried down the hawsers and anchor lines and disappeared into the city…The rats died by the thousands, and then the people began to die. It was the beginning of The Black Death — bubonic plague.”

Murnau’s film is also credited with making a new addition to vampire lore.

In the novel Dracula, sunlight can’t kill vampires. The first time that sunlight is mentioned as being fatal to vampires is Nosferatu. Grau and Galeen wanted to come up with a more dramatic ending and had Count Orlok die as the sunlight hits him.

While there is no doubt that the filmmakers did use Stoker’s story, Grau, Murnau, and Galeen put their interesting spin on it.

The film is occasionally shown on TV and included in Halloween film fests. Nosferatu has seen a remake with 1979’s atmospheric Nosferatu the Vampyre starring Klaus Kinski. We also can’t forget Shadow of the Vampire (2000) starring Willem Dafoe as Max Schreck and John Malkovich as Murnau. There’s also Nosferatu merch, including figures, novels, and comic books.

Nosferatu stands by itself and has earned its place in horror history.

Despite its obvious origins, Nosferatu is more than just another interpretation of Bram Stoker’s classic story. It stands alone as an iconic and influential part of a long and storied tradition of cinematic vampires, and it has more than earned its place in horror history.

Fright Fun Facts About Nosferatu:

1. Max Schreck has the perfect name for horror films; Schreck means “terror” in German.

2. The film Shadow of the Vampire (2000) was inspired by a suggestion from a film critic, Aldo Kyrou. In 1953, Kyrou mistakenly said that the identity of the actor who played Count Orlok was never known. He suggested that perhaps the actor was a vampire in real life.

3. Nosferatu was not the first film based on Dracula. The first Dracula film was Dracula’s Death (1921) which was very loosely based on the novel. The film, directed by Karoly Latjay, follows a young woman who has nightmares after crossing paths with Dracula who is a musician and not a count in this film. No copies of this film survived. The only proof of its existence is publicity photos.

4. Nosferatu was filmed on location in Germany in the cities of Lubeck and Wismar. The exterior of Orlok’s castle was filmed in northern Slovakia. Orlok’s castle is 700-year-old Orava Castle, located near Oravsky Poozamonva, a fishing village.

5. Producer and artistic director Albin Grau was inspired by artist Hugo Steiner-Prag who created the illustrations for a novel adaptation of, The Golem (1918), a horror serial written by Gustav Meyrink.

6. The film’s German premiere was on March 4, 1922, at the Marble Hall in the Berlin Zoological Gardens. The premiere had been heavily promoted for months in the press and was quite an event. There was a live show before the movie complete with a musical number and a costume ball afterward.

Follow Us!