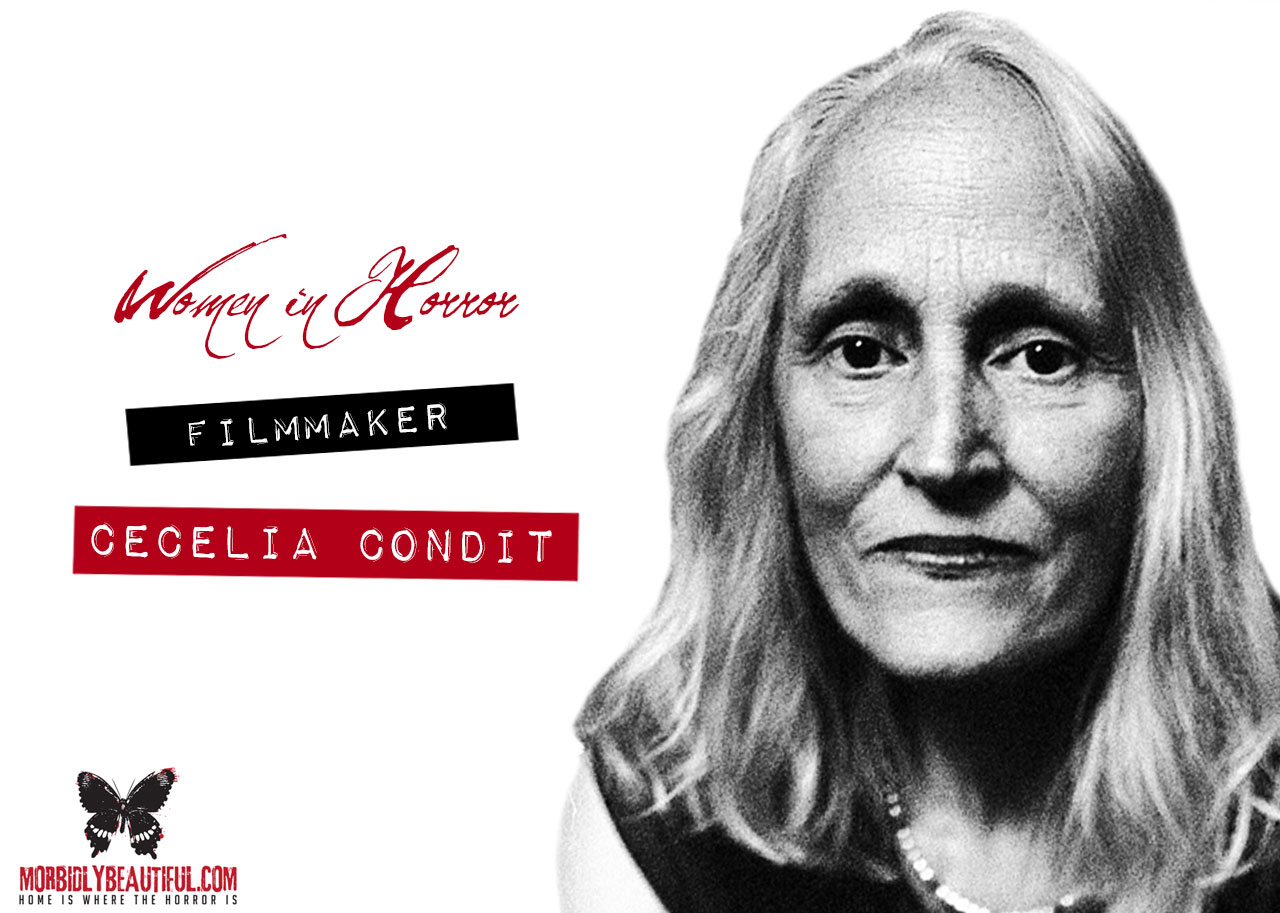

We sit down with one of the most underrated figures of experimental filmmaking, Cecelia Condit, to discuss inspiration, feminism, and much more.

I found Cecelia Condit’s work through a good friend of mine who knew how much I loved scary movies. The first film of hers I ever saw, through them, was 1981’s Possibly in Michigan. It was weird, wonderfully and beautifully so, and I proceeded to watch all of Condit’s films in a miniature marathon. She’s one of a few filmmakers to upload their entire oeuvre online (to both Youtube and Vimeo), making it accessible to the point where snippets of her work have appeared on TikTok of all places. In spite of this, her impressive body of work is still widely unknown.

I think that’s an absolute shame. Her work is amazing, and more folks should know about her. That’s why I contacted her and interviewed her on her life, her work, and what comes next. She’s absolutely brilliant and I hope you’re as delighted by her as I am.

INTERVIEW WITH CECELIA CONDIT

1. What’s your favorite scary movie?

I make scary movies, but I have a difficult time watching them. My own personal experience of ‘horror’ is quite intense enough, as became clear with my first viewing of The Silence of the Lambs. At the time, I unexpectedly had to take over a screening of the film for a co-teacher during of a major university lecture class. I had never seen The Silence of the Lambs, and I was supposed to offer my impressions at the end of the film. However, I was utterly too shaken and speechless. I have no idea what the class thought of me (crazed, I suspect), but I did get home – in spite the overwhelming sense of being stalked by Hannibal Lecter.

2. What inspired you to become an artist? To use video?

Both my parents were artists/painters, so from an early age they had a natural influence on my becoming an artist. My epilepsy limited my vocational options, and I rationalized that making art might allow me to express all those crazy, raw emotions that loomed so heavily on me when I was young. When I discovered the video medium, my need to tell stories found a home. Video also allowed me to work free from the baggage of history and traditions, where I felt I might be excluded.

3. What are your biggest influences when it comes to your current work?

The biggest influences in my current work still oddly grow out of childhood experiences. I was raised in an old house tucked deep into the woods of Philadelphia. There were streams on three sides, and the only entrance was a windy dirt road filled with endless pot holes and mud. Though beautiful, my childhood was also isolated.

Subjected to intense sibling bullying, I struggled to define myself and my image as a girl. Looking back, I was always making books filled with drawings of women. Even then, making art was my way of exploring who I am — all the while keeping my head down.

4. Your first film, Beneath the Skin, was released in 1981, and you’ve been making short films pretty steadily ever since then. How has film-making changed for you since you first made Beneath the Skin?

I am forever a storyteller, but the stories I tell have changed drastically as I evolved and matured. Over the years I find I have been facing various issues, such as memories and aging; but the importance of friendships, and the grounding of myself in the natural world, have become clearer and clearer.

In the making of my first piece, Beneath the Skin, I discovered channels to put my own rage and fear into perspective, as well as see what happened as just another story “that happened to my life.” Although it is not the only freaky story I survived, it prompted me to start a dialogue in which each piece I make speaks to the others, giving the body of my work added complexity and depth. Their totality has become somewhat like a memoir with more to come.

5. The first film of yours I’d ever seen was 1983’s Possibly in Michigan. What inspired that piece, and Arthur’s shape-shifter nature?

The relationship between my first two videos is strong. The final words in Beneath the Skin are “I dreamed that it was me and not her that he killed two years ago, but that’s another story.” Possibly in Michigan is that ‘other’ story. It is a revenge story about a masked “Animal/Cannibal” man named Arthur who follows two women home from a shopping mall. He then transforms into the role of victim as they kill and eat him.

In much of my work, men are presented as brutal shape-shifters. Throughout the film, Arthur transforms through male stereotypes such as a Pig, Wolf, Frog Prince, and Prince Charming, ultimately mutating into a deadly cannibal with a continually opened mouth.

In my dreams from childhood, the faces of men were always masked and often dangerous. Perhaps they wore masks because what was underneath was too disturbing, or perhaps they represented the duplicity of the men I knew growing up. I have become aware that there is a division between my art practice and my life.

In my videos, I have hated men. But over time, it has become clear to me that what I truly hated is what is now called ‘toxic’ masculinity. And really, who doesn’t hate that? It is mean and forces us to fly in face of the ‘power over another’ syndrome that leaves women, children, and innocent people vulnerable to its poison.

6. In your recent work, you’ve played a lot with natural backgrounds and landscapes like parks (Tales of A Future Past), backyards (Some Dark Place), and abandoned places (Pulling Up Roots). What draws you to these places?

Filming in open natural spaces is one of my favorite aspects of my work. I often spend so much time inside editing projects that it is comforting for me to watch images of singing birds and landscapes that I’ve explored earlier with my camera. The sense of the wild, and its danger and unpredictability, is a force in my filmmaking.

Sometimes it is portrayed in blurred backgrounds with swinging doll’s arms, or a dead deer I stumble across in a friend’s woods, or my small unkempt backyard where a girl finds a dead rat and an imaginary friend. Conversely, even parking lots and suburban shopping malls are as significant to me as abandoned ruins, like Pulling Up Roots (2015), where memories linger and surround the protagonist.

7. Your latest piece, We Were Hardly More Than Children, is an emotionally brutal exploration into trauma and the history of abortion/how people who’ve had abortions have been treated. Do you think we’ve had a lot of progress since the events of the film happened? When it comes to the future of abortion rights in America, do you think we’ll continue making progress?

We Were Hardly More Than Children (2019) is a freaky epic story of friendship, but also of failed relationships and irresponsible responses from the medical community around a friend’s abortion. Over the years, I have relived that evening so many times in my mind that I believed that this project would be easy to make. That proved to be wrong.

I realized early on that the traumatizing trigger for me was ‘blood.’ I couldn’t film blood. It was hard for me to even say the word ‘blood.’ However, the color that permeates the film is red, and I understand now, that as intense and deeply personal as this film is, it is an understated version of the reality of this really troubling night.

On various occasions over the past 50 years, I have naively thought that our society settled archaic practices concerning abortion and women’s basic human rights; however, with each new generation, the battle over abortion sadly needs to be fought all over again.

8. All of your films, at the time of this writing, are on Vimeo and YouTube. Do you think the digital landscape is a good place for experimental filmmakers to archive and showcase their work? What drawbacks have you found?

The internet is a great screening platform that bridges the gap between high and low art, as well as the public and private. While it opens a door for anyone, anywhere to share their work, the vast number and variety of movies and songs on the internet make having a film go viral a bit like winning the lottery. In fact, going viral implies inspiring viewers under 40. Even my work about older people has been seen mostly by young people online.

My own intense internet experience began in 2015 when an excerpt from Possibly in Michigan made the front page of Reddit. Then, in the summer of 2019, sixteen-year old Virs Dillard uploaded a 20 second musical clip from Possibly in Michigan onto TikTok. It became part of a creative and fun viral phenomenon with thousands and thousands of performances lip syncing to Karen Skladany’s songs, “Oh no, no, no, no…silly” and “Animal/Cannibal.”

With the success of these two songs, YouTube started recommending Possibly in Michigan to thousands of young people surfing the web. The number of views,” “likes,” and “replies” have established a connection to people I would never have otherwise known.

I get quite a few emails and find that some can be rather touching, coming in waves — as though passed from friend to friend. A few of them are funny: “Would you be my grandmother?” All have been respectful and thoughtful. However, with this enormous exposure, I have felt a sense of vulnerability that is a bit unnerving.

I try to cherish it, as it is also an unexpected honor. It also increases the level of exposure to all my work. Some people write me that my short videos are often a place not just of death, but of sanctuary. They intimate to me that if I can move through such difficult experiences, perhaps they can too.

9. You’re not just a filmmaker of course, you’re also a photographer and a musician. What medium do you like best: music, photography, or film?

I am primarily a filmmaker who also writes songs. Nevertheless, sometimes it is a pleasure to take time off and make still images, which I find both calming and fun. I think of my songs as poems, and writing their lyrics allows me to define the project in a magical essential way. The songs create complex spaces that enrich the narrative and compound the impact of the visuals.

Over the years, I have been fortunate to work with a number of wonderful composers and musicians, such as Christopher Burns and Paul Amitai. However, I would like to highlight the collaboration I have had with singer, songwriter, and composer Karen Skladany, as she wrote “Animal Cannibal,” the musical piece which went viral. I would also like to draw attention to Stephen Vogel, as he composed music for three of my videos, Not a Jealous Bone, Oh Rapunzel, and Little Spirits.

Last, but not least, I would like recognize Renato Umali, who most recently has composed and performed music for Pulling Up Roots, Some Dark Place, Tales of a Future Past, and We Were Hardly More Than Children. At times, each of their music is so present and powerful, that my stories become simply a vehicle for the music’s own brilliance.

10. All of your works have focused heavily on women’s connections: to their own memory, to the Earth, to each other, to the people around them. What keeps bringing you back to this point of inspiration?

I do think there is a profound sense of community between women who have been through violence and injustice. This community has always been important to my work, and I do not work alone. My films involve friends and their stories and insights. Often, it is a manifesto to friendship, feminism, fearlessness and may society be damned.

Playing the beautiful, long dark-haired Sharon in Possibly in Michigan, Jill Sands appears in my earliest pieces from 1981-1987. I call it my Jill Sands Trilogy. We have a friendship that has continued over decades. She saved me from a brutal nightmare of my own making and still contributes significantly in many ways to my work.

It is a friendship that began in 1981 when I spotted Jill at a gallery opening in Cleveland, Ohio. I approached her and said, “Hi, would you like to be in a video?” She replied, “Okay” and laughed.

We Were Hardly More Than Children was inspired by Diane’s powerful paintings, and the epic tale of an abortion we lived through when they were illegal. Some Dark Place, with Gail Zivin, addresses memory and loss. Linda Girvin plays the giraffe in Tales of a Future Past, and Flora Coker is an actress and friend who appears in both Oh, Rapunzel and We Were Hardly More Than Children. Rooted in friendship and identity, my videos were an exploration in friendship from the beginning.

11. Your website mentions that you’re currently working on a film about “the universal language of how women are unknowingly lured into a pattern of abuse, humiliation, and domination”. Can you tell us more about that?

Having finished We Were Hardly More Than Children, I am now working on several videos that may turn into one larger project. First of all, I am collecting stories about abuse inflicted by family members and partners. These tales of abuse against women are varied, but the patterns are the same. Strangely, only the details and the severity seem to change.

Also, my son Lloyd Vogel took photographs for me while leading a backpacking expedition though the Alaskan Artic. Ants walk across the photographic images, and I place pebbles on the men’s heads – that are like masks, disguising them. My intention is that these images will add life and contrast to some of the stories these women tell of the men who silenced and hurt them.

12. What advice do you have for anyone who wants to follow in your footsteps?

I truly find this question difficult to answer. I take a step at a time, and I am not hard on myself if I am too busy to spend more than a few hours working on a project per week. Still, I always know what my next step or shoot is. Then when I have time, I apply myself and pretend that disappearing from the outside world is a natural way of life.

Follow Us!