As Blumhouse plans to revive the least celebrated Universal Monster, we look back on The Invisible Man’s representation in film, spanning from 1933-2018.

When someone says “Universal Monsters” there are a few names and images that come to mind immediately. The erroneously labeled Frankenstein (instead of Monster), the romantic Dracula, Wolfman, The Creature, and even the Bride. Seldom, and fittingly so, is the name of Jack Griffin, aka The Invisible Man, mentioned.

With the announcement that venerable production company Blumhouse would be restoring visibility to the classic Monster, it was time to dust off the bandages and look at just where the story has gone through the years since H.G. Wells first introduced us way back in 1897, in novel form.

The History of “The Invisible Man” on Film

An Invisible Man Walks the City (1933)

Much like many technological advancements during wartime, the Germans beat the US to the punch, releasing this interpretation of H.G. Wells story one month before the James Whale classic. Nicknamed “Dynamite Director” for his Michael Bay-like fondness for blowing things up, Director Harry Piel saw success through the second World War by becoming a member of the Nazi party, although even he poked the irrational Bear a bit too much when he was reportedly scolded for his use of realistic explosions and aerial attacks, striking fear into the psyche of the German people. After the war, his party affiliation landed him imprisoned and unemployed, and he would live out his life rather miserable.

Much like many technological advancements during wartime, the Germans beat the US to the punch, releasing this interpretation of H.G. Wells story one month before the James Whale classic. Nicknamed “Dynamite Director” for his Michael Bay-like fondness for blowing things up, Director Harry Piel saw success through the second World War by becoming a member of the Nazi party, although even he poked the irrational Bear a bit too much when he was reportedly scolded for his use of realistic explosions and aerial attacks, striking fear into the psyche of the German people. After the war, his party affiliation landed him imprisoned and unemployed, and he would live out his life rather miserable.

In this rendition, Piel also steps in front of the camera playing a Cab Driver in his own name. A chance encounter with a fare on the run leaves Harry with a mysterious suitcase containing a harness and helmet, which looks a bit “Marvin the Martian”. A flick of a switch turns Harry invisible, and a panic ensues until he settles in to his new-found powers. Harry’s flat mate Fritz suggests robbing a bank, but Harry has a more honorable path to wealth; he sells his cab and bets it all on a horse race that he uses his invisibility to fix.

Harry uses his winnings to rent a mansion with Fritz and woo an actress who was a regular fare — after a local florist, down on her luck and facing eviction, rebuffed his misogynistic, caveman-like advances. Ultimately betrayed by Fritz, who steals the suitcase and uses the device for his original plan — robbing a bank. Harry does all he can to thwart Fritz. A rather impressive, especially for the time, car/motorcycle chase ensues, with some real shots. Fritz attempts to escape via Zeppelin, and another impressive action scene, with Harry hanging from the blimp by a rope. Harry makes his way up the rope and into the cockpit before Fritz finally throws him from the vessel.

Harry wakes up from the fall to realize the whole encounter was a dream. He’s called on by the Police who are looking for the suitcase from his fugitive rider. It ends up the device was a new, innovative Pilot’s helmet. The Man, obviously not a criminal, rewards Harry with a large sum by check, to which Harry uses to pay off the Florists lease. The whole ordeal ends much happier than Piel’s real life, as Harry becomes engaged to Annie the Florist, and they ride off into the proverbial sunset in his cab.

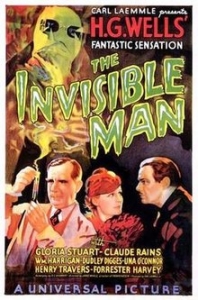

The Invisible Man (1933)

Here it is: THE Classic. I truly fell in love with this film. I had only seen it once before, and I don’t know I gave it proper attention. From the moment the plane circles the globe, and the Universal logo fades into a declaration of adherence to the NRA (National Recovery Administration; a product of FDR’s “New Deal” which set labor standards and practices, albeit very temporarily), the base is set. This is the foundation we work from. Words on a page can make a man invisible with simple adjectives, but filmmakers must adapt, compromise, and innovate to achieve the unachievable — erasing a man.

Here it is: THE Classic. I truly fell in love with this film. I had only seen it once before, and I don’t know I gave it proper attention. From the moment the plane circles the globe, and the Universal logo fades into a declaration of adherence to the NRA (National Recovery Administration; a product of FDR’s “New Deal” which set labor standards and practices, albeit very temporarily), the base is set. This is the foundation we work from. Words on a page can make a man invisible with simple adjectives, but filmmakers must adapt, compromise, and innovate to achieve the unachievable — erasing a man.

Ignoring upwards of fourteen different treatments based on Wells’ 1897 novel, but dragging the story as farfetched as Russia and even one based on Mars, Screenwriter R.C. Sherriff made the appropriate decision to stay closer to Wells’ source material. The structure was for the most part maintained, with some minor story changes, which in my opinion make it more relatable. A deeper conflict, a love interest, an explanation for egotistical madness. And humor. The only original “Monster” to come out of the Universal stable and break up the terror with laughs. Perhaps to offset the body count, the highest of any as well, which at an exorbitant 122 rivals any modern-day shoot em’ up.

Director James Whale, who also gifted us visual interpretations of the Monster in “Frankenstein” (1931) and the often considered superior, “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935), decided to cast the unknown stage Actor, Claude Rains, based off hearing him audition from another room. A fitting introduction. It was a brilliant decision on Whale’s part, as surely ego would have seeped from the pages of the script and driven any self-important “Movie Star” to demand more face time. Rains enjoys literal seconds of his face being on screen as his character, Jack Griffin, dies at the close.

Coloring in the lines set by Wells, Griffin hides out at an English Inn aptly named “The Lion’s Head”, in order to complete a secret experiment. Enter the original steampunk icon, with his face wrapped with bandages and welders’ goggles. The bar patrons and Landlord speculate as to his origins. A criminal on the lamb being the leading theory. Griffin continues to try and solve the problem of permanent visibility as we are introduced to the love interest, his former employer’s beautiful daughter, Flora (played by Gloria Stuart, most famously known as Old Rose in James Cameron’s “Titanic”). Jack has disappeared and Flora and her Scientist Father, along with colleague Kemp, are worried about him. Griffin promptly wears out his welcome at the Inn and receives the boot from Mrs. Hall (played fantastically by Uma O’Connor) and her husband. The eviction is punctuated with the hilarity of a Three Stooges-like chase of a button-down shirt around a chair, and the mistaken clobbering of the wrong guy.

“A few chemicals mixed together, that’s all, and flesh and blood just fade away. A little of this injected under the skin of the arm for a month. An Invisible Man could rule the world. Nobody will see him come, nobody will see him go. He can rob and rape and kill.”

I suppose the madness that is settling into Griffin’s brain can explain away why a man who presumably has never robbed, raped, or killed before, would suddenly find the notion so enticing. Maybe they missed the intention of Wells’ instigation in the novel. A Socio-Anarchist, surely, he meant to play on people’s fear that all Man would be evil given the slightest sniff of power.Perhaps it was just sensationalist dialog (that would be explored and brought to fruition in later versions). In any case, after Kemp and the Scientist have found some of Jack’s research he has, in staying within the source material, turned up at Kemp’s looking for a partner. Kemp’s desire for Jack’s flame, Flora, told us early on this wasn’t going to be harmonious. He plots with Kemp, hoping to murder and maim anyone they please, but must retrieve his journals from the Inn first. Here, Jack makes his first kill, the Police Inspector at the Inn.A man hunt is launched, using and suggesting many methods that are mostly thwarted as Jack listens in on some of them. Jack derails a train (accounting for the large body count). Having promised to kill Kemp for double-crossing him, he fulfills said promise by tying Kemp up and driving his car off a cliff. In closing, Jack is discovered in a barn by a farmer and the Police have him surrounded. His footsteps in the snow reveal his position, and he’s shot. On his deathbed, with Flora by his side, he reappears — skeleton first — followed by the strikingly fair and beautiful Claude Rains. It’s been posited that Whale killed off both Jack and Kemp because of his distaste for sequels. Oh, how he underestimated Hollywood’s penchant for ignoring canon in the name of financial opportunity.

The Invisible Woman (1940)

Released the same year as the sequel, this is the first departure from a straight horror film. I found this film very enjoyable, but I can’t shake remorse for what could have been a groundbreaking film if Women were taken seriously. The plot revolving around a Woman who’s sick of her and her colleagues being mistreated by her Male boss makes sense, but the assumption of subservience accompanying a female character is indigestible. This is such a common thread throughout the films I’ve researched here I can’t help but dissect it and deem it a dark stain on civilization (yes, I know I’m not making a pioneering statement, but it deserves attention).

Released the same year as the sequel, this is the first departure from a straight horror film. I found this film very enjoyable, but I can’t shake remorse for what could have been a groundbreaking film if Women were taken seriously. The plot revolving around a Woman who’s sick of her and her colleagues being mistreated by her Male boss makes sense, but the assumption of subservience accompanying a female character is indigestible. This is such a common thread throughout the films I’ve researched here I can’t help but dissect it and deem it a dark stain on civilization (yes, I know I’m not making a pioneering statement, but it deserves attention).

All that said, hey, we have a studio film starring a Woman! A very charming and commanding Virginia Bruce who plays the part of Kitty with assertiveness.

Hollywood heavyweight John Barrymore plays a mad-type scientist, Professor Gibbs, who’s benefactor’s wealth has dried up, thanks to his playboy antics. Searching for a willing human test subject, his only volunteer is Kitty. Of course, he’s surprised at her sex, but moves past his fear of “skirts and things” as his options are nil. Mrs. Jackson, a servant played by the one and only “Wicked Witch of the West” Margaret Hamilton, assists Gibbs as he wishes to maintain appropriate behavior with a nude Woman. Another departure from past, there is no serum, it’s a machine that achieves invisibility this time.

Once invisible, Kitty ignores Gibbs wishes and instead goes right for her misogynistic boss. Scaring the devil into him, he has an epiphanic moment that he should be nicer to Women and his employees specifically. A pretty, fun scene of Kitty modeling a dress, headless (she models clothes for big money buyers) punctuates the whole sequence.

A group of thugs hunt down Gibbs through his advertisement for test subjects. At first, I found this trio of goons to be a lame Three Stooges knock off, before I finally realized that oddly enough, Shemp Howard (Shemp) was one of said thugs. They’re representing their boss, Gangster Blackie Cole, who’s hiding out in Mexico and wants the machine to make himself invisible and cure his case of being homesick. Blackie ends up obtaining the machine, but does not have the accompanying serum, so the machine just inflicts a high-pitched voice on the occupant.

Although Kitty became visible again, it’s discovered that alcohol reinstates the invisible state. She uses this to her advantage and going forward, besides thwarting Blackie and his gang, it seems every character’s purpose is to get Kitty and the benefactor, Dick Russell, together. Some well thought out (-sarcasm-) lines of dialog such as, “If more Women were invisible, life would be much less complicated,” make sure to sever any inkling of control Kitty may have over her destiny as a sentient, autonomous, human.

Of course, Dick and Kitty get together in the end and have a baby. While changing the progeny, the butler, played by Charles Ruggles with expert comedic timing and support, slaps some rubbing alcohol on the baby (a practice of yesteryear?), and it’s discovered the power of invisibility has become hereditary.

The Invisible Man Returns (1940)

Presented as a sequel to Wells' Invisible Man, rather than the film, there is a more polished and modernized feel to this film, but it all falls short. It lacks charm, and its humor is flat and mistimed. The story has a more rigid structure, and a reduction of characters makes it easier to follow actors I had no inkling of recognition for. Suspiciously the special effects, which were so impressive in the first film, carry a level of ineptitude.

Presented as a sequel to Wells' Invisible Man, rather than the film, there is a more polished and modernized feel to this film, but it all falls short. It lacks charm, and its humor is flat and mistimed. The story has a more rigid structure, and a reduction of characters makes it easier to follow actors I had no inkling of recognition for. Suspiciously the special effects, which were so impressive in the first film, carry a level of ineptitude.

John P. Fulton continued his revolutionary Special Photography duties, so there should not have been any fall off in skill. Affirming my speculation, the budget for this film was about 20% less than “The Invisible Man”. Famously it stands as the first Horror movie of the one and only Vincent Price, although he is invisible for the majority.

Geoffrey Radcliffe is engaged to be married to Ms. Helen Manson (who is played by the truly stunning Nan Grey), but he is imprisoned for the murder of his Brother. Before he can be executed for the crime, Dr. Frank Griffin (Brother to the original Invisible Man, who on a case file they inexplicably rename John) injects him with the serum that will aid his escape, and path to exoneration. Once freed and donning an homage to Jack’s attire in the original, Geoffrey makes his way to a remote cottage with Helen while they try to figure out how to prove he wasn’t the killer.

Meanwhile, Griffin works on an antidote to reverse the invisibility, so far at the expense of some lab animals, with no success. Geoffrey is forced on the run by a nosey Police Officer. After a visit to Griffin’s lab arouses suspicion about promotions within the Radcliffe mining company, Geoff follows the newly elevated Mr. Spears and “plays a ghost” to extract the information out of him that Geoff’s cousin, Cobb was the one who murdered his brother, and made Spears lie about it

A showdown closes out the action, with Cobb dying in a fall and confessing his sins before he gasps his last breath. Geoff steals clothes from a scarecrow, which could have been clever earlier in the story, but here we’re just carrying on. It’s time to button this up. Griffin intends to operate on Geoff to save him and performs a blood transfusion. Trying to figure out how to operate on something he can’t see, his problem is solved when the new blood itself cures Geoff’s invisibility. An impressive sequence of his body reappearing; cardiovascular system, veins, nerves, musculature, bone and finally skin. A handsome — but more Vincent Price than most of us are used to — Vincent Price embraces Helen.

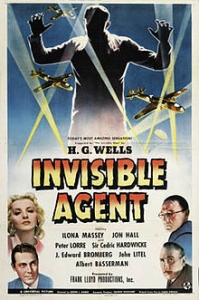

Invisible Agent (1942)

The fourth of five “Invisible” films that John P. Fulton lent his expertise to visual effects. None hold up to the original, and that is not meant pretentiously. This is the beginning of what would become a common theme for most repetitions going forward: using invisibility for military gains.

The fourth of five “Invisible” films that John P. Fulton lent his expertise to visual effects. None hold up to the original, and that is not meant pretentiously. This is the beginning of what would become a common theme for most repetitions going forward: using invisibility for military gains.

German spies visit a man living a humble, secret life believing he holds the formula for invisibility, which he does. He’s the grandson of Frank Griffin, similarly named, from “The Invisible Man Returns”. He averts their attempts at stealing the formula and is approached by the US government but rebuffs their request for the formula, claiming nothing can justify its use. Enter the attack on Pearl Harbor. This has swayed Frank’s feelings and he agrees to sharing the formula if he alone is the subject.

Sent on an espionage mission behind enemy lines, Frank parachutes, becoming invisible and shedding his clothes in mid-air. Frank meets up with a contact, a German double-agent named Maria. A subject of romantic interest of a German officer named Heiser, Maria worries about the consequences of them discovering Frank. An odd use of powers has Frank stealing Heiser’s food and eating it as he and Maria dine. The more Heiser speaks the more transparent it is that there is a strong element of propaganda to this film. A mere fraction of the cinema produced as pure Nazi propaganda in Germany, and no claims put forth of the character of the Nazi soldier rings false once history has been told, nonetheless interesting.

Heiser’s superior officer, Stauffer played by Cedric Hardwicke who returns after playing Cobb in “…Returns”, is onto Frank and sets a trap, which is unsuccessful. Frank ultimately makes off with a list of Japanese and German spies within the US and learns of a plan to bomb New York. A Japanese Officer is played by Austrian actor Peter Lorre, who finishes off Stauffer before going all hara-kiri on himself. Frank and Maria escape in a German plane, bombing the air field and subsequently preventing the attack on New York.

Back behind Allied borders and in hospital Frank removes makeup to show he’s once again visible, much to Maria’s delight (did people really fall in love this easily back then?). Frank denies her request to divulge how he became visible again, dubbing it a “military secret”. A cool little spy film that underutilizes its resources.

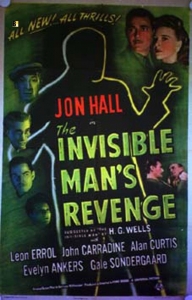

The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944)

Fulton’s swan song in the series. This is the epitome of the misogynistic and sexist nature of Hollywood writing as it pertains to this thesis. Where the insertion of a love interest as the B-story worked to humanize Griffin in the original, here it’s forced and rapey. It’s a serviceable film at best, with the weakest acting yet. Zero relatability.

Fulton’s swan song in the series. This is the epitome of the misogynistic and sexist nature of Hollywood writing as it pertains to this thesis. Where the insertion of a love interest as the B-story worked to humanize Griffin in the original, here it’s forced and rapey. It’s a serviceable film at best, with the weakest acting yet. Zero relatability.

Robert Griffin (no stated relation) is bitten with a bout of amnesia, but remembers he’s been swindled out of his share of a diamond mine. He visits his former partners, who thought him dead, and threatens them for his take. He displays fondness, creepily so, for their daughter Julie. The wife, Irene, drugs him and has him kicked out.

Griffin befriends a vagabond, and they unsuccessfully try to litigiously milk the couple for money. Griffin then stumbles upon a Doctor, who just happens to have discovered invisibility and sees an opportunity for his first human test subject. Once invisible, the already evil Griffin, continues his “reign of terror”. A blood transfusion makes the Doctor’s dog visible again, and Griffin demands the same, vampirically stealing the Doctor’s blood and killing him. The visibility doesn’t last, and Griffin realizes he must seek more blood.

He beelines for Julie’s fiancé Mark. He’s forestalled in his plasma acquisition by none other than the Doctor’s dog Brutus, who kills him in a wine cellar. The final, and singular redeeming trope is dialog pointing out that forbidden places were probed too deeply. “What a man earns he gets. Nature has a strange way of paying him back in his own coin.” Rings true even today, and we could benefit from paying closer attention to that warning.

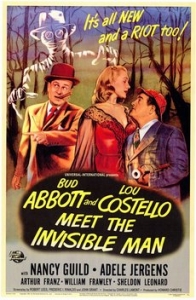

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (1951)

After making a comeback with “Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein”, a script planned as a direct Invisible Man sequel was changed into an Abbott and Costello vehicle. It must have been for the better, as Lou Costello’s talents are on prime display. They duo briefly “met” the Invisible Man (voiced by Vincent Price), at the end of the earlier monster mash-up film. The house used in this film (labeled 823 Maple Street) would later go on to be used as 1313 Mockingbird Lane, The Munster House.

After making a comeback with “Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein”, a script planned as a direct Invisible Man sequel was changed into an Abbott and Costello vehicle. It must have been for the better, as Lou Costello’s talents are on prime display. They duo briefly “met” the Invisible Man (voiced by Vincent Price), at the end of the earlier monster mash-up film. The house used in this film (labeled 823 Maple Street) would later go on to be used as 1313 Mockingbird Lane, The Munster House.

The story follows Bud and Lou, playing characters similarly named, as newly minted Private Detectives. A role that feels natural for their skill comedically. They’re visiting by Boxer Tommy Nelson who’s suspected of killing his own manager after a bout. He hires Bud and Lou to help him find out who really committed the crime. The undeniable chemistry between Bud and Lou, despite their past turmoil, oozes out of every moment. Their acting contrasts each other so beautifully.

Tommy and the boys go to visit Uncle Phil, a Doctor, who has a serum (called pripitane in this film, as opposed to monocane and duocane previously) that will turn Tommy invisible and offer him a chance to investigate. A nod to Griffin, with a photo of Claude Rains hanging on the wall, has Tommy worrying about going insane from the serum.

Tommy disappears right in front of Lou’s eyes, leading to some great old-time jokes. The entire film is filled with well performed gags. Exactly what you could and should expect in a story involving an invisible character. A card game, with obvious advantages, a bar fight where the bubbly pacifist Lou benefits from his transparent friend, and climatically a classic boxing fight, with Lou fighting a real pro with Tommy’s help. With the real killer discovered, a gangster named Morgan who sought retribution for Tommy not throwing a fight, Tommy ends up stabbed although the gang has prevailed over the thugs.

In the hospital, a blood transfusion is performed to save Tommy, with Lou acting as donor. Some blood has “backed up” into Lou, and once Tommy becomes visible again, Lou becomes invisible. Ending on a great gag, where Lou takes advantage of his new yet temporary powers to nuzzle up to an elevator of nurses. He becomes visible again at an inopportune time and somehow his feet end up on backwards. A faux pas I am remarkably willing to ignore based on pure enjoyment.

The Invisible Man (TV Series 1958)

Following the premise of “Invisible Agent”, this UK based series follows Dr. Peter Brady who falls invisible thanks to a radiation leak in his lab. He’s a scientist “engaged in highly secret experiments towards man’s conquest of space and matter and mysteries of the future.”

Following the premise of “Invisible Agent”, this UK based series follows Dr. Peter Brady who falls invisible thanks to a radiation leak in his lab. He’s a scientist “engaged in highly secret experiments towards man’s conquest of space and matter and mysteries of the future.”

A rather apropos scenario for cold war storytelling has this episodic journey spinning some interesting yarns, many of which pull at the “Iron Curtain”. An absolute breakout star is Deborah Watling who plays Brady’s young niece, Sally.

Standout episodes include “Crisis in the Desert” featuring the exotically beautiful Adrienne Corri as an undercover agent in the middle east on a rescue mission and “Play to Kill” featuring the uber talented Helen Cherry who plays a famous actress being framed and blackmailed. The whole series stands up as watchable, albeit dated, especially for those fascinated with all the hullabaloo around the technology race of the Cold War.

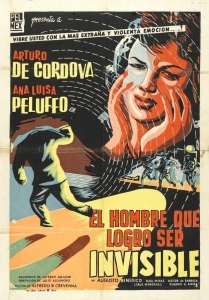

Invisible Man in Mexico aka Invisible Dead aka The New Invisible Man (1958)

I watched the English audio version, which anglicized the characters names. Following a similar plot to “The Invisible Man Returns”, the main character, Charles, finds himself framed for murder. His brother Lewis – the scientist – and his fiancé Beatrice, do all they can to get him out.

I watched the English audio version, which anglicized the characters names. Following a similar plot to “The Invisible Man Returns”, the main character, Charles, finds himself framed for murder. His brother Lewis – the scientist – and his fiancé Beatrice, do all they can to get him out.

Lewis presents himself as a prison Doctor in order to inject Charles with the serum and facilitate his escape. Some old themes play out, with a mobster having committed the murder in question to cover up an embezzling scheme. A lot of religious overtones are utilized in the dialog, and this film stands to have the most significant take on societal regression. There’s so much substance to the dialog, it would be hard to ignore this film as inspiration if you were to play in this world.

In the end, Charles succeeds in clearing his name, but the side of humanity he has witnessed while invisible has turned him.

“Mankind has contaminated it’s soul with corruption and evil. Therefore, all souls must return to him (God) so they can be purified…I’m going to destroy all life…The time has come for a new race. I am his messenger."

This is the finest example of the threat of madness that most of the other films promise.

A holy war is set to erupt with an army of one. Attempting to poison the water supply with encephalitis, Charles is stopped before he can kill his love, Beatrice. The big showdown: The Cops corner Charles at the water supply, but as they open fire, Lewis jumps in front to save Charles, and dies from his foolish actions. Charles is hit, but alive. In hospital the Doctors can’t remove the bullet since they can’t see it (with no explanation of why the bullet isn’t visible), until they use an antidote left behind by Lewis to make Charles visible again. We end with Charles heading to surgery and seemingly facing no consequences.

Orloff Against the Invisible Man (1970)

Ape rape. That’s all there is really to say about this film. A very difficult film to sit through start to finish. The film seems to have been developed in a sewer. The single redeeming quality I can find is the score is reminiscent of Ennio Morricone (a personal favorite).

Ape rape. That’s all there is really to say about this film. A very difficult film to sit through start to finish. The film seems to have been developed in a sewer. The single redeeming quality I can find is the score is reminiscent of Ennio Morricone (a personal favorite).

Odd seduction, mongoloid slaves, a dead daughter who returns from the dead with no explanation or questioning, an invisible Ape with a penchant for raping Women who need clothes with some more secure fasteners, and a plot as decipherable as the Ape is visible.

I stared at the TV for a bit after this one, until I instinctively blurted out to myself “What the fuck did I just fucking watch?"

Now You See Him, Now You Don’t (1972)

A 21 year old Kurt Russell. Do I even need to sell it more?

A 21 year old Kurt Russell. Do I even need to sell it more?

This is a Disney film, but it doesn’t really feel like it. This is part two of their Dexter Riley trilogy. Based on college students finding some sort of super power through scientific exploration. I haven’t seen the other two films (but I did enjoy this one enough to warrant checking them out), so there’s some intrinsic rifts between characters that seems to have been set up already from the first film that is just lost on me. Regardless, it’s easy to get a line on which character falls into which archetype.

Centered around the science department at a small college. The Dean, Wiggins, is bringing in an investor to help pay the mortgage the school can no longer afford. The science kids discover the investor happens to be a gangster looking to turn the college into a casino/gambling center. Dexter discovers the power of invisibility by accident, and luckily for them and for the film makers, it’s washable. A hose or bucket of water is all it takes to wash the serum off.

They devise a plan to win a science award that would be for the exact amount of money that the college owes for the year, $50k. Dean Wiggins clearly doesn’t trust them, and the school doesn’t even have an invitation into the competition, so a plan is devised for the Dean to play a round of golf with the award chairman. Of course, they use the serum to improve the Dean’s abysmal handicap, and a few trick shots later they’re in.

Their demonstration of the serum doesn’t go well, as the gangster, Arno (played by Cesar Romero, familiar as the Joker in Batman 66’) has stolen it. Arno uses his newly acquired tool to rob a bank and the kids do their best to help the police stop him. With just seconds left before the science award is unveiled Dexter makes a bumbling Dean Wiggins invisible, and the money is theirs.

A slight nod to the original Invisible Man, when one of the students stung by bees is wrapped in bandages. This is the first film that the power is used for purely positive, and lacks any sense of corrupting its subject, but that makes sense because, ya know, the Mouse. Family fun and enjoyable.

The Invisible Man (TV Series 1975)

Besides the original film, this is the most invested I became in the content.

Besides the original film, this is the most invested I became in the content.

I was reluctant given the age of the material, but I was bought in and let down by the end of the 13 episodes that there wasn’t more to watch. Created by Steven Bochco (NYPD Blue, L.A. Law, Etc.) and starring David McCallum (best known as “Ducky” Mallard from NCIS, or Ilya in “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.) as Doctor Daniel Westin, who is endearing and a surprisingly effective secret agent, it’s a shame this didn’t catch on more in the states. It is alleged on the cover of the Blu-Ray that religious groups protested the series because it “featured a naked man”.

Antithetical to most of the other content, a machine is used to accomplish invisibility. The Pilot episode stands out, with an adversarial relationship between Westin and his employer, black ops government contractor – KLAE Corp. as much darker in tone. By the end of said episode, Westin has destroyed the machine to prevent KLAE Corp from giving it to the military and exploiting its power, but there is no transition, as in the second episode the relationship is all copacetic and no mention of Westin’s rebellion is made.

All talk of trying to make Westin visible again is also abandoned. Cleverly, Westin and his wife Kate, played by the enchanting Melinda O. Fee who instills a much, needed injection of strong muliebrity, seek out a former colleague Doctor Maggio who has created a skin grafting treatment called dermaplex that is used throughout the series as a latex like mask and miraculously makes Westin look completely normal.

Invisibility was achieved by using a chroma key method much like what meteorologists use when providing you with weather guesses every morning. Reportedly the effects were performed live on camera, instead of in post, which expedited the editing process as well as saving money, but the technique results in some very odd visuals and color gradients.

An episodic experience, with each installation being a new mission for the Westin’s to use Daniel’s power to aid or solve problems for good. Many of the episodes are strong and entertaining, but the “Go Directly to Jail” sticks out as exemplary.

The episode “Stop When Red Lights Flash” sticks out as well, not only because it’s good fun, but it rings very familiar plot wise. If you’ve ever seen the Chevy Chase vehicle “Nothing but Trouble” (hate on it if you’d like, but you’re wrong), then it’s hard to not make a connection that Dan and Peter Aykroyd must have seen this show before they wrote that film, minus the whole Penis nose and bone crushing rollercoaster. It’s just too close to be a coincidence. I know Aykroyd has stated it’s based on a personal experience he had, and I’m not refuting that, but there had to be some more inspiration to fill in the rest of the story. Don’t get me wrong, “Nothing but Trouble” is one of the most enjoyable films of my childhood, and Aykroyd is one of my favorite comedic actors.

I would highly suggest this series, especially because I can’t ignore my prepubescent progeny's demands for me to put it back on.

Astral Factor aka Invisible Strangler (1978)

Another hard one to watch. The best part of this may just be the poster, which features a young Will Ferrell-ish man hovering over a pool with a yawning nude woman, a floating head, and an armless bust of a blonde woman.

Another hard one to watch. The best part of this may just be the poster, which features a young Will Ferrell-ish man hovering over a pool with a yawning nude woman, a floating head, and an armless bust of a blonde woman.

Filmed with what I assume was a Nokia 3310, a prisoner in the hospital for the criminally insane uses his mental powers to astral project himself invisible, although it’s not really projecting since he just becomes invisible completely. He escapes to kill every woman that reminds him of his mother, who was a famous socialite and embarrassed of him. The killer disappears (I don’t mean becomes invisible) from the film for a while, and then it’s over and he’s dead. Move on.

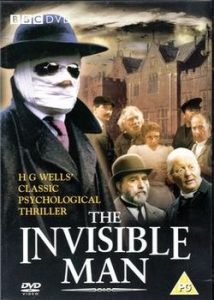

The Invisible Man (BBC TV Series 1984)

This is for all you originalists out there. You know who you are. The ones that always say, “the book was better”. Which it always is, but not in this case. The James Whale film pushes the potential of the book where it needed to go.

This is for all you originalists out there. You know who you are. The ones that always say, “the book was better”. Which it always is, but not in this case. The James Whale film pushes the potential of the book where it needed to go.

This BBC production is as close to the Wells source material as you can possibly get. I hesitate to call it boring, but my skin didn’t crawl with excitement. It’s stuck in time. Feels much more 1800s than 80s, which I suppose was the point, but that doesn’t make me want to watch it anymore. They did the source justice, and Wells. It was an accomplishment of loyalty and execution.

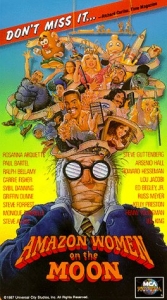

Amazon Women on the Moon (1986)

This is a sketch comedy film presented by John Landis. Landis has long been associated with horror because of the inarguably brilliant “An American Werewolf in London” and most likely his handling of MJ’s “Thriller” video/short film, but I always felt his hand was cosmicly guided for comedy. The segment of the film, directed by Carl Gottlieb (who penned Jaws 1-3 as well as Steve Martin’s “The Jerk”), is titled “Son of the Invisible Man”. It stars Ed Begley Jr. (who actually had a small part in Disney’s “Now You See Him, Now You Don’t) as Griffin, the son of the original Griffin.

This is a sketch comedy film presented by John Landis. Landis has long been associated with horror because of the inarguably brilliant “An American Werewolf in London” and most likely his handling of MJ’s “Thriller” video/short film, but I always felt his hand was cosmicly guided for comedy. The segment of the film, directed by Carl Gottlieb (who penned Jaws 1-3 as well as Steve Martin’s “The Jerk”), is titled “Son of the Invisible Man”. It stars Ed Begley Jr. (who actually had a small part in Disney’s “Now You See Him, Now You Don’t) as Griffin, the son of the original Griffin.

He believes he’s duplicated his Father’s formula and runs invisible, and naked, through the Lion’s Head Inn. He sneaks around messing with the patrons; moving game pieces, throwing darts. He’s inevitably arrested by Polic,e as he is not in fact invisible and just a naked man running around a bar. Super short manifestation of something that was probably a joke in every person’s mind who ever contemplated being invisible.

The whole film is worth a watch if you’re into that Kentucky Fried Movie type of thing.

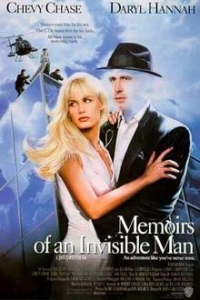

Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992)

Maybe I’m just a Chevy Chase fanboy. I liked this as a kid, and I like it now. It’s his patented humor and cockiness. Developed from a similarly titled book by author HF Saint, who made a hefty chunk of change off the sale of rights and then jumped ship from the literary world. Oh yea, directed by John Carpenter.

Maybe I’m just a Chevy Chase fanboy. I liked this as a kid, and I like it now. It’s his patented humor and cockiness. Developed from a similarly titled book by author HF Saint, who made a hefty chunk of change off the sale of rights and then jumped ship from the literary world. Oh yea, directed by John Carpenter.

Not only is this missing a score by Carpenter, but it also misses his unique voice. It’s not a bad film, although it has moments of mediocrity, it could have been served with a touch of The Prince of Darkness’s quirkiness. There’s a reason he is a heralded deity amongst our community, and it’s not because some fucking suit thought their ideas were best channeled through Carpenter’s vision. Someday, maybe someone with the checkbook will realize that.

All that aside and accepting that we are not getting a true Carpenter hatchling, the movie is familiar and comfortable. Injecting Chase’s propensity to play a dick spot on into that familiarity works for me.

One element that truly blows this up is reluctance to keep Chase invisible. He was too big of a star to keep off the screen. He would inexplicably be visible to the audience and then invisible again within the same scene. There needed to be a rule set from the jump, and there wasn’t. No respect was paid to the audience in that regard.

Stumbling upon the power of invisibility, his character, Nick, clashes with a CIA like character played by Sam Neill and finds a love interest in Alice Monroe, played by Daryl Hannah. I’m not sure the plot offers anything unique for me to warrant many more lines, but what does is the effects. This was the birthing of digital effects.

Even if you find this film disposable, it’s importance in proof of concept for digital effects is critical. Achieved by Industrial Light and Magic using techniques they learned from “Willow” and “Terminator 2” (according to an accompanying featurette on the DVD), the pre-Mocap effects are impressive. It set a standard, a base if you will, for the entire industry to build on. Another fact of note: this is the first “major Hollywood studio picture” with a score completely composed by a woman, Shirley Walker. And it’s fucking good.

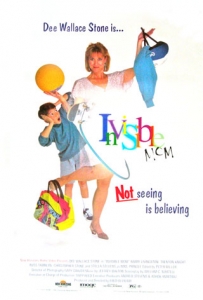

Invisible Mom (1996)

What am I doing? Could have been an episode of the Goosebumps TV series from the 90s. I’m not knocking Goosebumps, as I’m a fan, but it could have upgraded whatever it is I just watched. Starring Dee Wallace (E.T., Critters, Cujo, etc.) and directed by Skinemax legend Fred Olen Ray (I dare you to give his catalog a go from front to back).

What am I doing? Could have been an episode of the Goosebumps TV series from the 90s. I’m not knocking Goosebumps, as I’m a fan, but it could have upgraded whatever it is I just watched. Starring Dee Wallace (E.T., Critters, Cujo, etc.) and directed by Skinemax legend Fred Olen Ray (I dare you to give his catalog a go from front to back).

This is the epitome of 90s direct to video. Nothing more to report, except the Mom is the one that becomes invisible in this one. Watch at your own risk, or if your time is worth nothing to you.

Hollow Man (2000)

Much like John Carpenter’s “Memoirs…” this film, directed by Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Starship Troopers), shows no characteristics of being helmed by anyone familiar. But, Bacon butt, man. Kevin Bacon plays Sebastian Cane, a scientist whose team has already achieved invisibility but works on “curing” it. A great example of updated effects enhancing words on a page, the transformation from visible to invisible and back is awesome. The tone is dark, and foreboding.

Much like John Carpenter’s “Memoirs…” this film, directed by Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Starship Troopers), shows no characteristics of being helmed by anyone familiar. But, Bacon butt, man. Kevin Bacon plays Sebastian Cane, a scientist whose team has already achieved invisibility but works on “curing” it. A great example of updated effects enhancing words on a page, the transformation from visible to invisible and back is awesome. The tone is dark, and foreboding.

Elisabeth Shue, Josh Brolin, Kevin Bacon’s dong; you can’t go wrong. It certainly has that early 2000s feel to it, but it’s so much grimier (most likely Verhoeven’s depraved touch, and I mean that as a compliment). Cane descends into true psychosis; raping and murdering. A big ending with lots of fire and explosions and a crane shot out while the survivors embrace in an ambulance tops off a film that honestly holds up for me.

The Invisible Man (TV Series 2000)

This may be putting my view to the test that not everything needs a reimagining when new technology allows it, but we’re far enough removed from this show that I still hold out hope. Centered on an unlikable criminal, Darien Fawkes, played by Vincent Ventresca, the best part of this show is bit actor Paul Ben-Victor.

This may be putting my view to the test that not everything needs a reimagining when new technology allows it, but we’re far enough removed from this show that I still hold out hope. Centered on an unlikable criminal, Darien Fawkes, played by Vincent Ventresca, the best part of this show is bit actor Paul Ben-Victor.

Fawkes is offered a chance out of prison if he allows himself to be a guinea pig for government testing, making him invisible, and then becoming an agent for “The Agency” working under “The Official”.

Honestly, the show jumped the shark for me in the third episode, and I had to abandon it completely. Episodic, like the '75 series, but completely lacking any sort of charm or cleverness.

The Invisible Man (2018)

This is ostensibly a student film, so I don’t want to rag on it too much. The actors and crew did their best to produce a piece of art, something I’m sure they all truly love doing. It’s hard to pick that apart with good conscious.

This is ostensibly a student film, so I don’t want to rag on it too much. The actors and crew did their best to produce a piece of art, something I’m sure they all truly love doing. It’s hard to pick that apart with good conscious.

What I can condemn is the absolute careless, useless, and gratuitous violence against children. If something of this sort truly serves the story, fine, but there are easy and cheap ways to perform such scenes without subjecting actual children to being tied up, with fake blood, and a knife held over them, for the sake of what? Fucking nothing.

Just like the idea that writing a sex scene is self-serving to the writer and should only be used as a true expression of art (cases that are few and far between) and not a screen minute muncher, more careful attention should be paid to the actual human you’re putting in front of the camera to perform your fantasies.

Produced by the Art Institute of California, which recently and abruptly closed its doors without notice, and predominately filmed on a theater stage, the actors did their best and some decisions are commendable.

Missed Titles:

- The Invisible Boy (1957) – with a story line featuring Robby the Robot from “Forbidden Planet” (1956) I regret

not being able to track this one down. - Gemini Man (TV Series 1976) – picking up right after the ’75 series, with a similar premise

- Invisible Kid (1988) – I could only find a YouTube version but it was unwatchable quality

- Invisible Maniac (1990) – same as above

- Invisible Dad (1998), Invisible Mom 2 aka Mom’s Outta Sight (1998), and Invisible Mom 2 (1999) – All three of these films are by Fred Olen Ray. I have no clue why there were two Invisible Mom sequels, but I respect my time too much to sit through anymore of his films.

A Story 122 Years in the Making

Often Hollywood is ridiculed for regurgitating stories. Sometimes though, the story is worth bringing up for a second chewing. The legend, Mick Garris, said, “Sometimes a great idea can benefit from an update… Sometimes it’s an opportunity for someone with a great imagination to reimagine a concept… A story worth telling.”

Dubbed the imagination to bring this story into the modern era is Leigh Whannell (Saw and Insidious franchises), who has been announced as Director. It will be interesting to see how Whannell translates his rather expert method of creating terror on screen into being afraid of that which you can not see.

Follow Us!