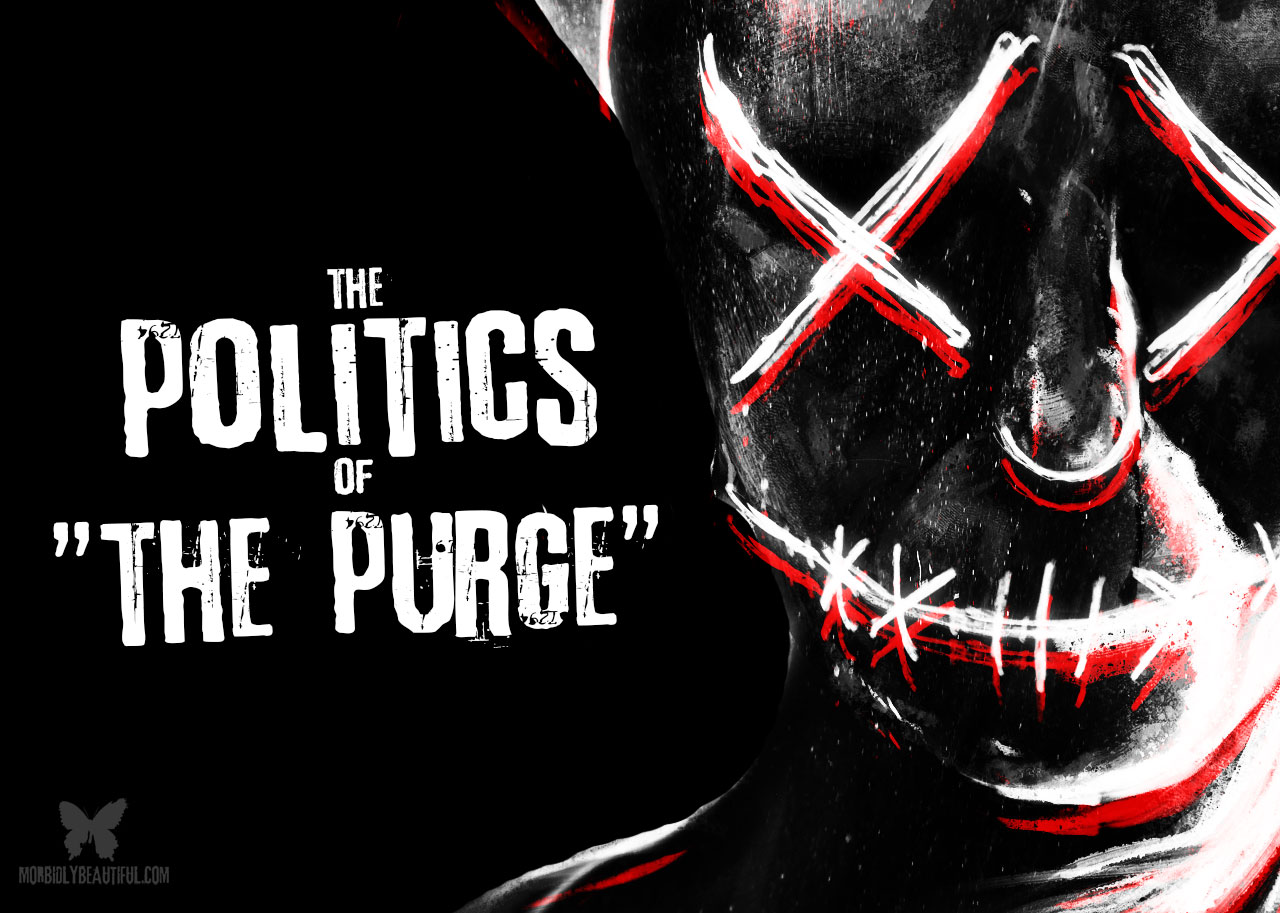

They may seem like simple, ultra-violent horror films, but “The Purge” franchise reflects a strong social message that’s more relevant now than ever.

The Purge movies were ahead of their time. The flicks (or at least the first three) are hailed as B-Movie fare, which kind of tells you where the line of respect for them lies. As horror junkies, we know that B-Movies often provide great insight, despite being generally pretty low budget and, let’s be honest, a bit extreme.

But it’s hard to look at everything happening in the United States now and not see the parallels between the fictionalized world of The Purge and where we are in our current reality.

In the spirit of complete transparency, I didn’t enjoy the first Purge when it came out. I went to see it in the theater with a group of friends. We were all so excited for the film, enticed by the promising premise. However, I was let down by the execution of that exciting idea. In fact, I had such a violent dislike for the first movie that, when I saw the trailer for the second film, I just rolled my eyes. I had no intention of watching it. But a fellow horror hound begged me to give it a chance — finally hooking me with the bait, “Dude, it’s a lot like Escape From New York.”

So I begrudgingly went to the theater, armed with minimal expectations. To my great surprise, it all came into perspective for me.

Multiple rewatches later, and I was now convinced The Purge movies would be revered as true horror classics.

So far, that hasn’t happened.

Sure, we got a third film in the franchise, and it even did well enough to pressure the studio into releasing an ill-advised fourth film. The success of the franchise even spawned a television show (that I still haven’t watched, because I am perpetually five years behind on TV).

In spite of all that, there has not been much chatter about the impact and relevance of these films. I’m surprised people didn’t see these movies as a sounding board for radical ideals, as inspired by revolutionary thinkers like Marx, Lenin, and Malcolm X.

While people tend to think of The Purge films as fun fodder about senseless violence and mayhem, they really speak to the uprising of oppressed people.

As black people across the country have been rising up to protest for change against a brutal and unjust system, I couldn’t help but think back to The Purge movies.

Though I didn’t love the first film when I saw it, I came to appreciate it in the context of the series. It represents the first in a step of revolutionary ideas; a perfect parallel to Marx’s Communist Manifesto.

However, what made this Purge movie so weak in relation to the two that would follow was where its gaze landed. We’re forced to follow the upper class — a white family that lives in a gated community with big beautiful houses, equipped with the best protective technology, in a predominantly white neighborhood. These people don’t need to worry about the Purge. In fact, the oldest daughter just throws in her headphones and isolates herself in her bedroom, without a care in the world.

For this family and others like it, the Purge is something that happens out there…not in here.

The family that we’re stuck with isn’t particularly vindictive or hateful, they’re just used to being protected by their privilege. The patriarch of the home, played by Ethan Hawke, buys fully into the propaganda surrounded the event: “This night saved our country.” When his son lets Dante in (credited as The Bloody Stranger, which we’ll get into later), he has no desire to protect him. He’s black and probably homeless, so Hawke believes he’s deserving of his fate.

When the young purgers show up at his door, they assure him they wouldn’t dream of hurting him and his family, because they are good and educated; you know, the way only wealthy white folk are.

Hawke’s character is not a hero.

He may be a hero for his family, but he is certainly not a man who wants to fight injustice. The mother seems to have been swayed in her thinking, after being saved by Dante, but how much of that will hold water? How much of what she says is just because Dante is protecting her in this moment? Is she the kind of person who will stand up against institutionalized injustice, or just disagree in silence while she hides in her bunker?

The lesson in the first Purge is simple: you can’t trust those who help keep you down to lift you up.

While the upper class might not want you to suffer, they will not risk their own comfort to help you.

I didn’t like this movie on its own, because I had no context of the world yet. The reason that the other films are easier to get into is because they get outside of the upper class suburbs.

The first installment is from the perspective of the insiders, not the outsiders. Our beloved freedom fighter Dante Bishop doesn’t even have a real name in the first Purge; he’s credited as The Bloody Stranger. His life doesn’t matter outside of being a victim for the son and mother to help protect, and a nuisance that jeopardizes white American comfort when he infiltrates their world.

And that’s why the second movie hooked me so hard.

I was finally able to see what my life would be like in The Purge.

Even more than that, I was looking at what life was already like. The only thing separating this film from reality is that the violence is visceral and happens one night a year. The US government is the accomplice to the murder of countless citizens every year — through abysmal health care, over-policing, low work wages, and sky-high rent rates — punishing people for the “crime” of being poor.

The series also equates the Purge with civil rights. Because of institutionalized racism, black people are more often than not at the bottom of the socio-economic chain. And, like The Black Panthers before them, the black community in Anarchy (the second installment) rises up to buck an unjust system that, literally, treats them like prey.

If the first movie ends with the Sandin family looking somewhat decent, this movie erases that praise. While they might not be the same rich people who make a mass profit off of the suffering of the poor by hunting them for sport and for the viewing pleasure of other rich folk, they certainly make money off of providing security for those people.

Carmelo Johns serves as our Malcolm X figure in Anarchy.

The movie never makes him seem like an unruly voice, crying, “We’re outraged, and we’re fighting back!” He’s trying to rally people together, trying to fight against the system, and is mostly shown inspiring young Cali to question the New Founding Fathers of America’s orders.

In fact, while some might peg Leo as the hero of this film, it’s really Carmelo, accompanied by Dante, who saves the day. Without the group of radicals rising to the occasion, the group we’ve followed throughout the film would be dead. Because, just as in the Black Lives Matter movement against police brutality, the point isn’t to pit black against white; the point is to stop injustice everywhere.

In my opinion, following Leo (a badass that I really do enjoy) in this film is a critical mistake, that’s doubled down on in the third entry.

His character is mostly stock, a white assassin meant to ground us and maybe provide us with a narrative to follow that isn’t black and poor people fighting for their freedoms, just in case that’s a little too radical for you. But he does represent an interesting figure in a revolution: the white person who works within the system to benefit the cause.

One of the most powerful moments is his decision not to kill the man he’s been stalking the entire film, because he has finally made an active decision not to use the system to his own benefit. He recognizes that he is somewhat untouchable in the Purge, and he understands that using the system makes him complicit in the abuse of the people he’s protected all night.

While you might be able to ignore the politics in Anarchy if you really focus on Leo, there’s no way to duck the message in Election Year.

Up until this point in Purge history, the richest and whitest class, politicians, have been protected. The rules are lifted in this installment because someone is trying to use the system to destroy itself. After all, if you want to make a change, you have to work from the inside, right?

Senator Roan finds out the hard way that the cards are always stacked against progress, as she is hunted through the streets with only Leo to protect her.

Election Year drives home the point that laws which destroy low income communities — and claim innocent lives — stem from the religious right. From the very first Purge, we’ve been shown that nationalism as a religion will lead to the destruction of the nation. Characters that go as far as to pray to the New Founding Fathers have been sprinkled throughout Anarchy and Election Year.

This makes the ending of Election Year all the more poignant.

Voting in someone new, someone who isn’t hyper right, should make things better. But by the end, it’s clear this isn’t enough. Riots are breaking out across the country because the right has lost their ability to kill without consequence.

We can only hope that there are enough people on the right side of history to fight back.

1 Comment

1 Record

eatyourchildren wrote:

Good article but how come it does not discuss the 4th Purge film? I would think the 4th film, The First Purge, would contribute to the thesis of this article given that it shows an even less privileged view of a Purge occurring, combined with a lot of behind-the-curtain back story as to how the concept of a purge was sold to the public and enabled for the far-right New Founding Fathers to take power. Are you just not a fan of the 4th movie?