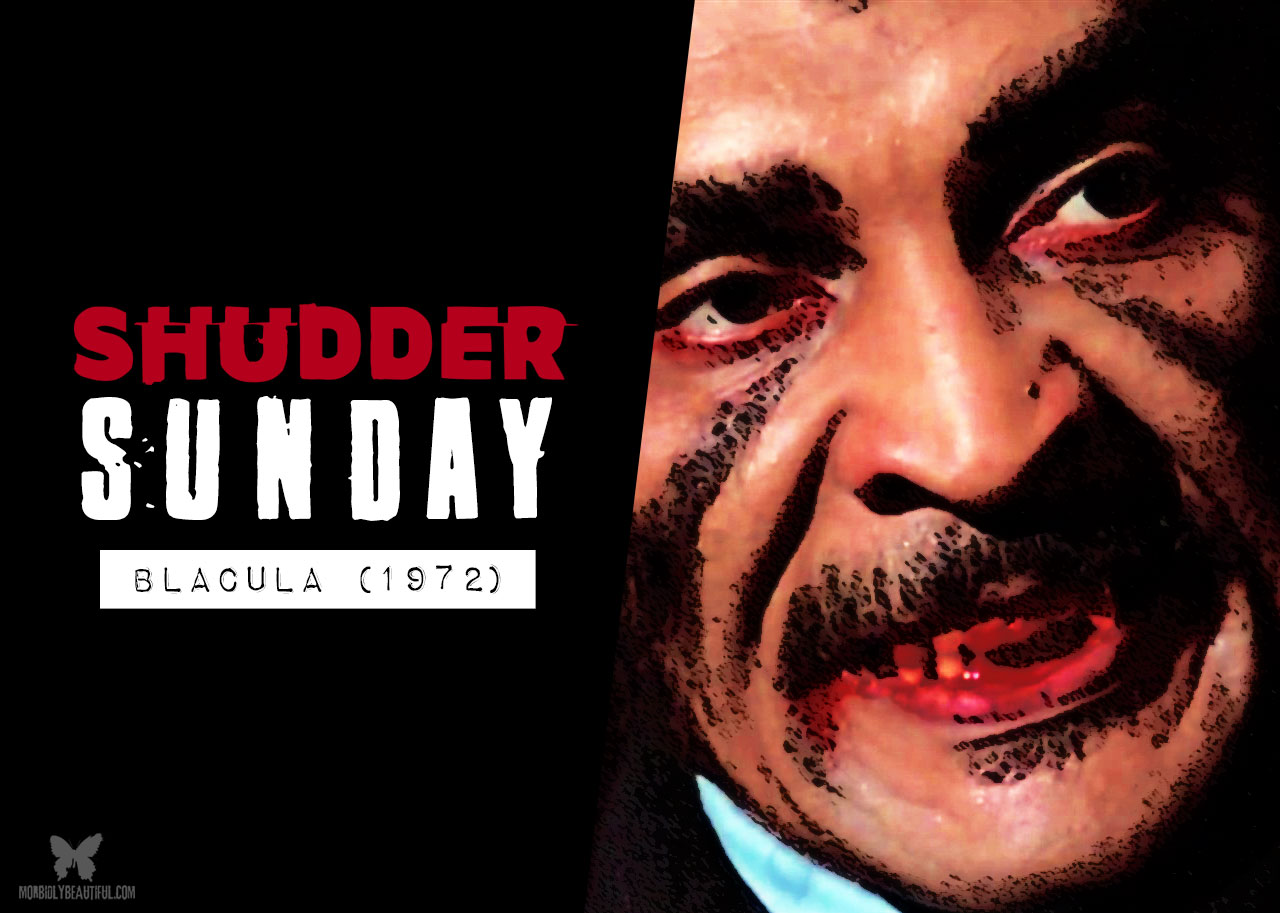

Unfairly resigned to silly shorthand for Blaxploitation horror, “Blacula” is essential vampire cinema that, like its tragic hero, hasn’t aged a day.

It’s not hard to imagine white flight audiences at the local drive-in giggling in their station wagons when Dracula dooms Prince Mamuwalde to suffer for all eternity with an insatiable thirst for blood and the name “Blacula.”

It’s a setup, not a joke, and the punchline comes after Saul Bass’s evocative credits, when the first spoken word is “Dracula,” by a Black man who can barely say it with a straight face.

It’s strange, if not entirely unexpected, that Blacula has become more myth than movie.

The title remains unfairly synonymous with Blaxploitation shlock, cementing the genre’s defining marquee template. See also: Blackenstein, the unreleased Black the Ripper, director William Crain’s follow-up Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde, etc. Even the name as a name, “Blacula”, lives on as pop culture shorthand in throwaway jokes from too many movies and TV shows to count.

It’s less strange, if still not entirely unexpected, that Blacula was coined as a compromise.

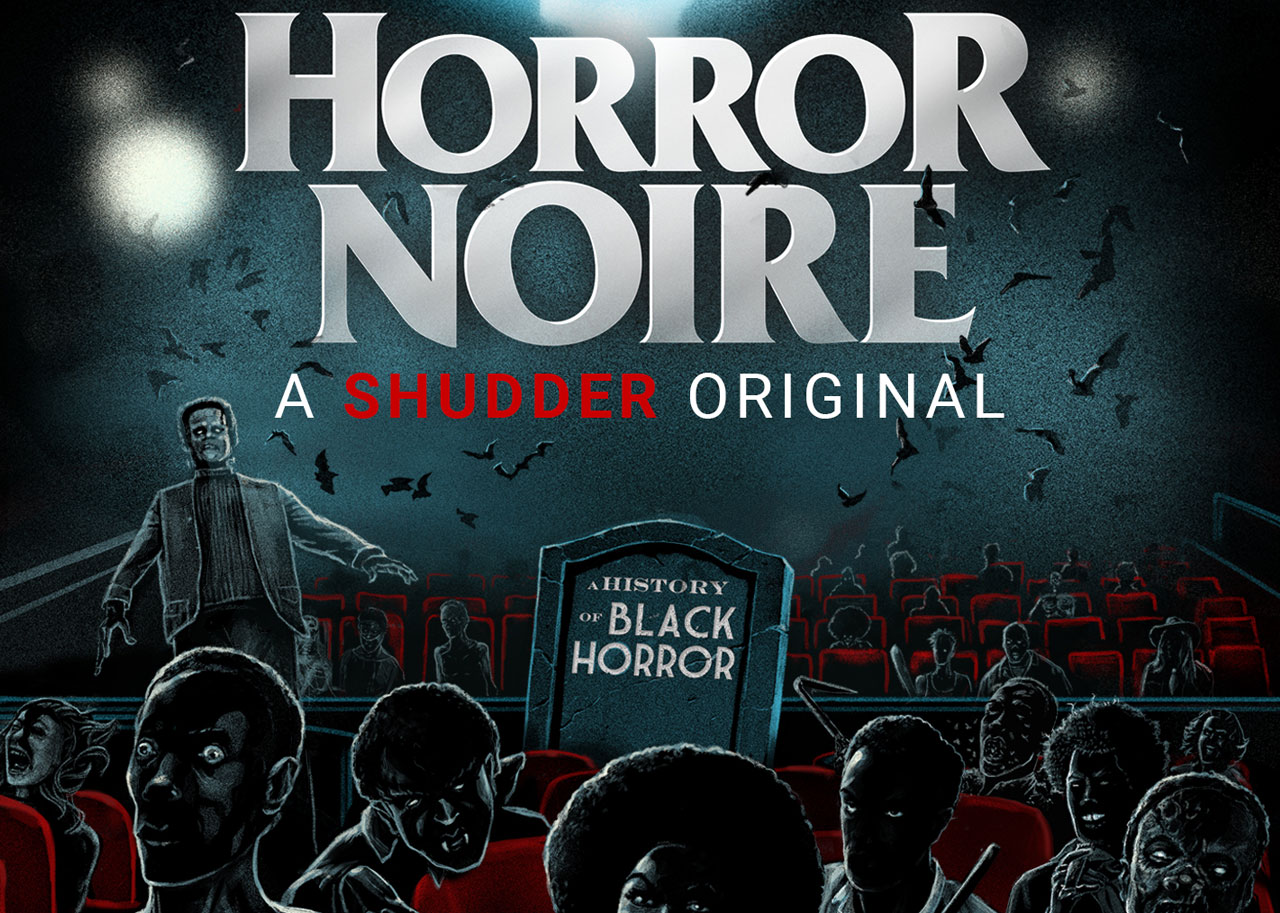

“They wanted to do Count Brown’s In Town,” says Crain in the essential doc, Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror. “So we decided we were going to do something else.”

Blacula is something else. It was “something else” enough to earn at least one headline: “William Crain, a black, selected to direct first black vampire movie.”

It’s something else when any work of art makes Dracula a player in the transatlantic slave trade by the two-minute mark.

The opening of Blacula is as traditionally Blaxploitative as it gets, with the Prince of Darkness subbing in for the conventionally corrupt white authority figure. But even the dialogue at its most Gothically heightened, Dracula damning his victim with “a curse of suffering…that will doom you to a living hell,” is loaded for bear.

The equivalence of racism to vampirism, an unchosen fate of tolerance at best and hatred at worst, haunts the rest of the movie like the impenetrable shadows of its animated credit sequence.

All that considered, it speaks volumes of the era’s censorship standards that the most offensive thing about the movie to American International Pictures was mixed race couples dancing in the background of a nightclub scene.

That was Crain’s call, after an assistant director first segregated the extras, but it didn’t come easy: “It went all the way up to Sam Arkoff.”

Introduce the titular character calling for the end of slavery in 1780, that’s all well and good. It’s in the past, after all. Show different races doing what comes naturally to any hit from The Hues Corporation in the polyester present of 1972, that’s a bridge too far. That’s not showing history, that’s showing progress.

Despite its recent cultural renaissance, Blaxploitation was a double-edged sword from its first double feature.

The talking heads of Horror Noire know the wound intimately:

“We went from maids to pimps and hoes,” says Thing star Keith David.

“They were images that were perpetrated by white people who exploited these images for their own gain,” says veteran Richard Lawson, whose first credited role came in the sequel Scream Blacula Scream.

“[American International Picture’s] was a strictly for-profit budget model, investing as little as they could and hoping something stuck,” explains Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman, author of the comprehensive text on which the documentary is based. “Their films would go on just a few screens in come cases, often in Black neighborhoods. Very low investment, very low quality.”

Once in a while the budgetary constraints of Blacula show through, mostly in the cross-fade transformations borrowed from Universal’s then-40-year-old playbook.

But it also never quite fits AIP’s slipshod mold.

The Black characters in Blacula are pathologists, antique dealers, and photographers. Though the depiction hasn’t aged well, at least one Black character is gay, something rare in its own right for the genre.

Once it jumps to the present, the movie downshifts into a familiar rendition of the Stoker story, at least Hollywood’s version.

Blacula’s coffin is moved across the sea, where he is unceremoniously awakened in a society that doesn’t know any better than to trust exotic strangers in capes. He sees the face of his lost love on a woman who’s never met him before. A snappy dresser with a doctorate follows his trail of bite marks, slowly believing the unbelievable.

Anyone tuning in for Shaft-as-Dracula will likely tune out disappointed.

Save Gene Page’s top-flight waka-cha-waka funk, Blacula is a pretty conventional retelling with an all-timer performance from William Marshall in the fangs. The coy Eastern-European eyebrow is nowhere to be found, no mallet behind Lugosi’s back that only the audience seems to notice. Marshall’s Mamuwalde is charming and commanding, a natural presence without any supernatural assistance.

His counterpart wink to Bela’s “I don’t drink…wine” feels more like a come-hither request: “I’ll have…a Bloody Mary.” He’s also not a monster.

Mamuwalde is a tragic ghost of historic pain, lost in a more forgiving time than his own, but not by much. Most of the Los Angelinos he turns are Black. They’d live forever if not buried so fast soon after their awakening, if the police weren’t hunting them down.

When Dr. Gordon Thomas, the turtlenecked Van Helsing analogue, tells Lieutenant Jack Peters, a colleague at least, that recent deaths may be connected, the cop doesn’t hesitate:

“There’s been a lot of Panther activity lately.”

Later, when the doctor studies the dead body of a Black woman, the white morgue attendant offers his unsolicited opinion: “If you ask me, she was looking for something.”

The police try to deny Thomas resources whenever possible.

The lieutenant finally believes him and hatches a plan in as much time as it takes to order it: “Better swarm the city with police, cars on every corner.”

Blacula watches from a rooftop, disgusted, as squad cars choke the streets below. It’s hard to say who’s an extra and who’s a passerby watching from behind the barricades, but there’s no confusing the effect of officers herding Black people along as white people gawk idly from the sidewalk.

If that doesn’t get your attention, the cop with the bullhorn will: “If we don’t get your cooperation, we’ll have to declare a curfew.”

When Thomas and Peters finally corner the vampire, it may be the doctor who throws open the coffin, but it’s the lieutenant who drives the stake. Into the wrong vampire.

When Blacula dies, as all titular Counts must, it’s by no one’s hand but his own. Denied his true love twice, he waves off his hunters and marches into the sunlight. A dignified death, as his body reduces to ash and earthworms. In another move from the Universal playbook, the movie ends with him.

Blacula earned AIP a small fortune, as proven by the sequel reaching theaters not even a full year later.

It also won the first-ever Saturn Award for Best Horror Film against the likes of Christopher Lee’s own Dracula in Dracula A.D. 1972.

Critical consensus was less kind. Judged as a blood-sucking shocker, most were unimpressed, despite a few mesmerizing jolts that still get under the skin. More than a few reviews took aim at its meager budget. The Monthly Film Bulletin, an outlet of the British Film Institute, deemed it a false-start for “an exciting new genre,” Black Horror, and accused it of having nothing on its mind past the prologue. Watched now, it’s hard to see anything but the point.

That’s the value of something like Horror Noire.

It’s an excellent resource — the doc covers Blacula, the sequel, Blackenstein, and Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde in detail — but it’s more than history, it’s missing context. Audiences showed up for Blacula. Critics shrugged it off as grindhouse fodder. White film historians sealed its fate as a gimmick, an unfit representative of a fraught genre in cinema, chosen because its name was silly enough to stick.

I hadn’t seen it before watching Horror Noire.

I knew the name and knew people who giggled at it and enjoyed it as that softest of pejoratives, for what it was. Had I not seen Horror Noire, had I not learned and appreciated the legacy of Black Horror, which is not quite so progressive as a lot of horror fans pat themselves on the back for, I wouldn’t have sought it out.

HORROR NOIRE is currently streaming for free on Shudder. Watch it, even if you’ve watched it already. It may be the only movie I’ve mentioned in this column that’d I’d recommend to anybody. Watching it isn’t activism, don’t be fooled, but it is education, and that’s where understanding starts.

If you’re looking for activism, a good way to start is with a Shudder t-shirt from Fright Rags through tomorrow night. All profits go to Black Lives Matter, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and the National Bail Fund Network.

Once you’ve watched Horror Noire and bought a shirt and looked around for how you can help your local protests, give Blacula a try. Tragically like its erudite hero, it hasn’t aged a day.

Follow Us!