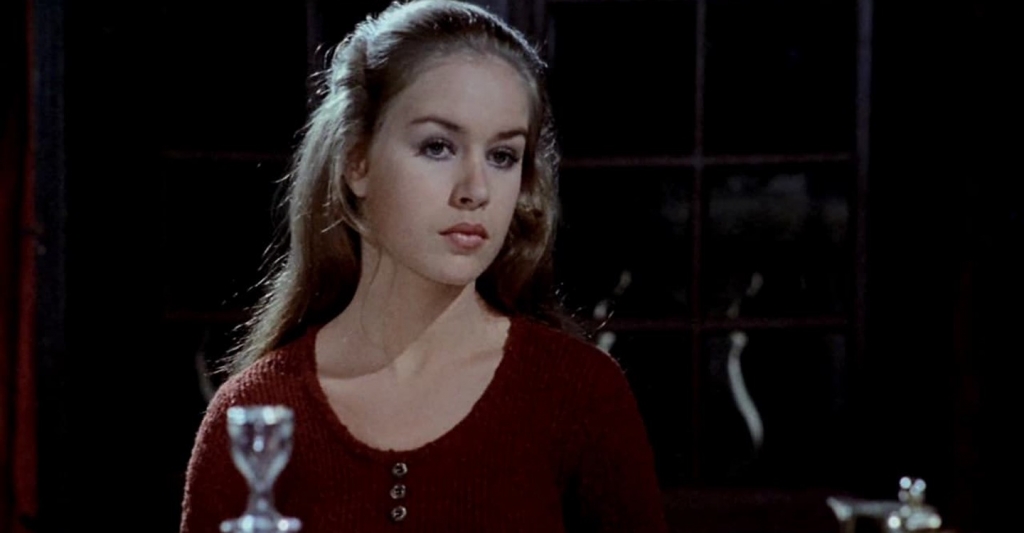

“The Blood Spattered Bride” is a brilliant exploration of oppression and the hunger for liberation masquerading as a stylish and sexy lesbian vampire film.

In the early seventies, lesbian vampires were having a moment. Hammer kicked things off in 1970 with The Vampire Lovers, and a dozen or so films featuring sexy, sapphic bloodsuckers cropped up over the next several years, mostly in Europe, before the trend ultimately ran out of steam in the second half of the decade.

In many cases, these movies were simply titillating tales of vampiric lust that sought to capitalize on increasingly liberal attitudes toward sex and nudity on screen. That isn’t to say these films have no cultural value — quite the contrary — but it seems that only a handful of filmmakers were using these tales to make a deliberate statement.

One of those filmmakers was Vicente Aranda, whose 1972 film The Blood Spattered Bride, a loose adaptation of Carmilla, is widely regarded as an allegorical rejection of fascism under the Francian dictatorship in Spain.

More directly, the film challenges the role of women under patriarchy, addresses the violence they suffer at the hands of men, and posits the lesbian vampire as a liberator and vigilante.

The film opens on a seemingly happy newlywed couple, but it’s clear from the beginning that all is not as it seems.

Virginal bride Susan has some well-founded anxiety about her new life, her new husband, and the expectations that come with her role as his wife. The honeymoon ends almost as soon as quickly as it began. They spend a few blissful days having sex all over the family estate, but Susan soon begins to resent and fear her husband’s increasingly predatory advances.

She also becomes obsessed with the story of Mircala Karstein, a 17th Century woman who married an ancestor of Susan’s husband and murdered him on their wedding night because of his “unspeakable” sexual desires. Mircala begins to haunt Susan’s dreams, enticing her to follow in her footsteps and violently murder her husband.

When a mysterious woman named Carmila appears bearing Mircala’s face, she and Susan embark on a bloody rampage of revenge for the violence that men have subjected women to for centuries.

There is always a question of consent in sexual/romantic vampire narratives.

The vampire wields a supernatural influence over their victims, causing them to bend to their will in ways they might not of their own accord. There’s room to read this influence as a kind of liberation, freeing the victim’s mind of inhibition and allowing them to act on repressed desires. This is especially true in lesbian vampire narratives; the vampire simply opens her victim’s mind to desires that have always been present but suppressed by a hetero-patriarchal society.

But there is still a power imbalance that is impossible to ignore, even though the lesbian vampire seducing a human woman away from her husband and her “proper” gender role is ostensibly a good thing. Different narratives deal with this imbalance in different ways.

In the case of Susan and Mircala, Susan comes to resent her husband without any help from supernatural forces.

From the film’s opening scene, her fear regarding her husband, sex, and the loss of her virginity is made plain. A rape fantasy gives voice to that fear, and when Susan’s wedding night with her husband mirrors that fantasy, the implication is that men’s sexuality is inherently violent. But despite her initial apprehension, Susan enjoys sex with her husband — at least for a while.

Eventually his advances become more predatory.

He tries to pull her up by her hair and pushes her to the ground, laughing like a child teasing little girls on the playground — boys will be boys. He then tries to force her to give him a blow job. She runs away, only to find herself running from him again and again, as she grows bitter and exhausted by his constant desire for sex.

Through all of this, Mircala observes but does not interfere. She doesn’t appear in Susan’s dreams until after Susan begins to stand up to her husband and outright refuse his advances rather than hiding from him, telling him he’d “better start learning what women are really like.” Susan already hates her husband; Mircala simply shows her what to do with that hatred.

If you haven’t figured it out by now, Susan’s husband doesn’t have a name. He’s credited as simply “the husband.” The only two other men in the film are “the doctor” and “Carol’s father.”

They don’t need names because they are every man — they are all men. The narrative validates Mircala’s misandry because all of these men are fucking terrible.

These men know nothing about women, reducing Susan to an “infantile” victim and Carmila/Mircala to a “paranoid pervert,” not for being a vampire but for being a lesbian.

Interestingly, this film is probably the only one of its kind of actually use the world “lesbian,” even if the men using that word obviously don’t know shit about lesbians either.

When Susan’s husband begins to suspect that Carmila is Mircala and a vampire, the doctor dismisses the idea but agrees that she is a threat to him because she has “dominated” Susan. The groundskeeper (“Carol’s father”) tells them that he came across Susan and Carmila together in the woods one night and heard them “howling;” he says, “they sounded like vampires.”

Now, I didn’t know that vampires had a special sound, but when the doctor follows Susan to another late night rendezvous with Carmila, the sounds we hear are the sounds of two women having hot sex. The doctor later describes the encounter to Susan’s husband as “a grotesque, insane scene,” as if the idea of women finding pleasure in each other, completely independent of men, is just as gruesome as the idea of Carmila being a vampire.

So needless to say, when Susan and Mircala go on a bloody rampage, no one feels particularly bad for these guys. In fact, you’ll probably find yourself cheering the gal pals on — and it feels like that’s what the narrative wants you to do.

In this way, the The Blood Spattered Bride feels more closely related to films like I Spit on Your Grave than The Vampire Lovers or other lesbian vampire films. The women’s wrath feels righteous.

They are ultimately destroyed by Susan’s husband in the end, but it’s not a clean-cut victory for the patriarchy.

The film’s last lines come from Carol, the groundskeeper’s 12 year old daughter who has been aiding Mircala, right before the husband kills her too: “They’ll come back. They cannot die.”

In an alternate, unused ending, Carol avoids being killed, opens Mircala’s coffin and puts on her rings, implying the vampire’s spirit — and certainly her hatred for men — will live on through her.

But this alternate ending lacks an important element that makes the true conclusion of the film more satisfying. The final shot of the film is a newspaper headline reading: “Man cuts out the hearts of three women.” This suggests that the husband is arrested for killing Susan, Mircala, and Carol, framing him as the “grotesque” murderer.

He may have vanquished the vampire, but he’s punished for it — and for his toxic masculinity. Mircala gets the last laugh after all.

Labeling any film as “feminist” or “anti-feminist” is tricky at best.

I will say that The Blood Spattered Bride presents some interesting and certainly progressive (for the time) ideas about gender and women’s sexuality that lend themselves to feminist interpretations. There are also valid criticisms; for example, some may find that the scenes of sexual violence feel exploitative.

The film’s feminist merits will no doubt continue to be debated. But if Vicente Aranda’s intention was to make a statement about the patriarchal oppression of women, I believe he succeeded.

‘The Blood Spattered Bride’ paints its heroine as a multidimensional character, then shows the ways that men cut women down to reductive labels: virgin, whore, bitch, etc. The lesbian vampire then becomes a liberator, setting human women free from the confines of patriarchy.

Mircala, Carmilla, whatever you call her — she may be a dangerous and violent creature in her own way, but sometimes we see that the world she offers is, at least to some of us, better than the alternative.

Follow Us!