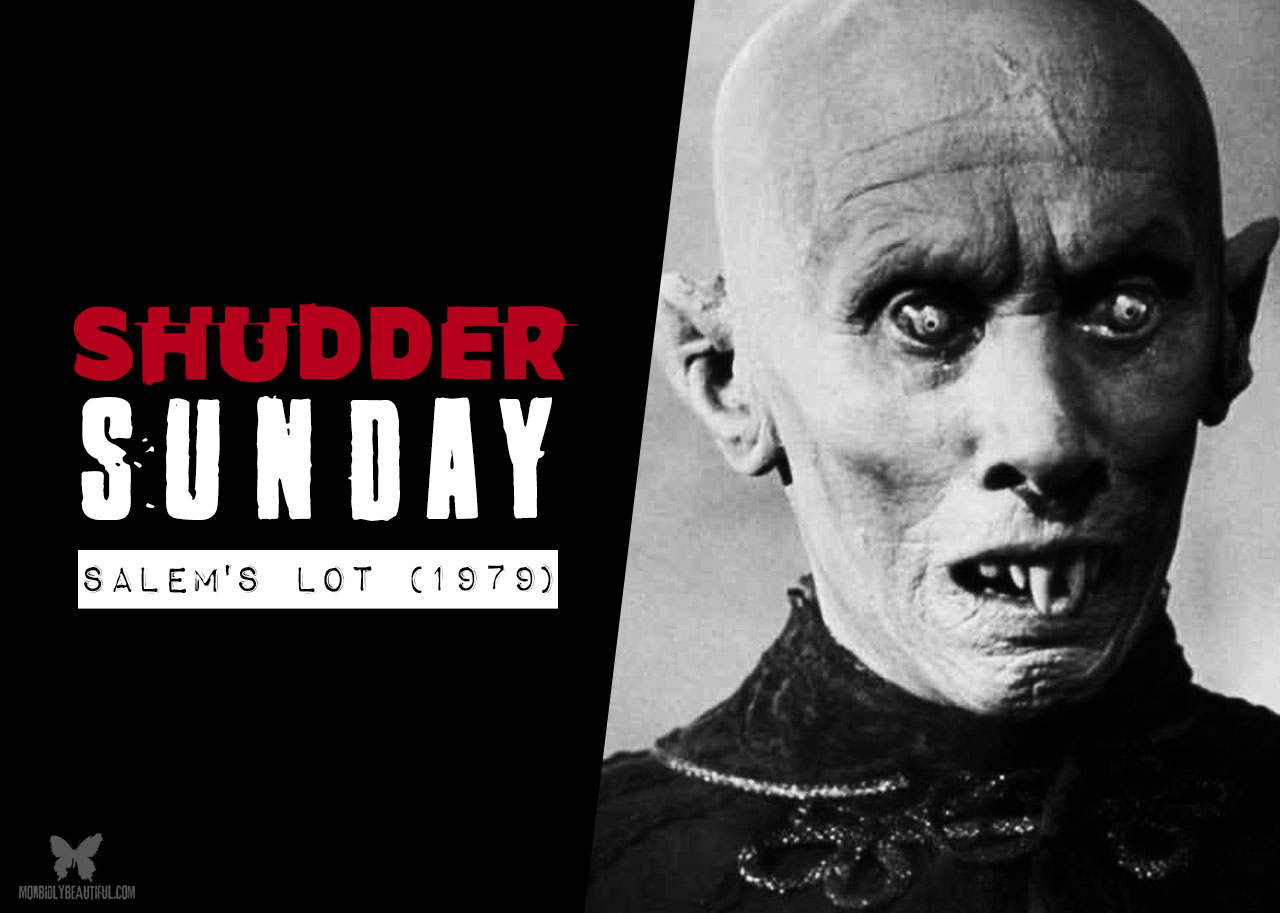

With network TV chintz that has only aged into better subterfuge for its late-game terror, the first Stephen King miniseries remains among the best.

In the nightmare world of Stephen King, bad places rhyme like drawn-out lullabies. It might take years or centuries to finish the chorus, just long enough for locals to nod off and forget. But it always ends right where it started, with bad people doing worse things in a town too tiny for a dot on the state map.

‘Salem’s Lot is King’s prototypical Bad Place, emphasis his — in 1981’s Danse Macabre, he considers the novel a flirtation with the same Bad Place he’d soon after drown in with The Shining. It’s a book about rough edges hiding in plain sight, with plenty of its own buried under prose so purple it bruises the fingertips. It’s near and dear to many Constant Readers, but mostly those who consumed it early in their romance. Before Lisey’s Story took the gold in 2006, King named it his favorite work whenever pressed.

With time and distance, another drawn-out lullaby, it’s easy to see the affection on both sides of the page — it is, in many ways, the first Stephen King book, emphasis mine.

After King’s first published novel, Carrie, moved over a million copies in paperback, his editor came calling about a follow-up. He had two in mind. One would later be published under his Richard Bachman pseudonym as Roadwork, a howlingly bleak story of an ordinary man turned Job without the benefit of a loving god. His editor suggested the other book, pitched as Peyton Place meets Dracula, was the smarter financial move, even if it risked branding him as a capital-H Horror writer.

The adaptation of the result, his Bad Place primordial, rhymed.

Tobe Hooper had the misfortune of launching his career with the scariest horror film ever made. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was so singularly infamous that it inspired an entire subgenre of rotgut exploitation. Hooper, much like fellow Master of Horror George Romero, could only find work within the narrow bounds he accidentally established. Unlike Romero, however, Hooper was never left to his own devices.

On Eaten Alive, his spiritual sequel to Chain Saw, Hooper walked off set after one too many arguments with producers. On The Dark, he only lasted three days before the brass fired him for falling behind schedule. By the late ‘70s, the clock was ticking to make the first Tobe Hooper movie and prove that he wasn’t a fluke but a capital-H Horror filmmaker.

The fact that he pulled it off on network television, under limitations that made Romero leave the project, is nothing short of miraculous.

Salem’s Lot — the first apostrophe was lost somewhere in preproduction — aired across two nights in late 1979, each half a two-hour broadcast. For years after, it was only available on home video in a scorched-earth 112-minute cut intended for European theaters. Now the full miniseries lives on, minus commercial breaks and unnecessary recaps, in a 183-minute cut that haunts streaming services with the regularity of Halley’s Comet.

Somehow that scarcity is appropriate.

The November 17th premiere, following a Puff The Magic Dragon special about lying and programmed against an episode of The Love Boat guest-starring Jimmie Walker, hit unsuspecting audiences like an atom bomb.

40-odd years later, it’s not nearly as shocking, but going in blind and expecting the constraints of prime-time CBS is still good for a contact high. I’ve seen it before, years back on another pass of the comet, and the jumps still got me.

You’ll just have to put some miles in before they show up.

In a prologue that’s both the weakest part of the book and the miniseries, a worn-out man and a worried boy fill bottles with holy water and panic when the bottles start to glow. It’s the worst effect in the entire three hours, no-contest. The entire scene is played again, verbatim, as part of a much more effective epilogue. It might’ve hooked viewers not used to seeing Hutch of Starsky &- fame ransacking a Guatemalan church, but now it’s just a speedbump on the way to an all-timer title card.

A creepy house under a creepy moon beside a creepy piece of pink typography spelling Salem’s Lot as Harry Sukman does an Emmy-nominated Bernard Herrmann impression.

It’s pure, unleaded atmosphere and a convincing case to stick out the occasionally glacial first half that follows, which at least has a worthwhile guide.

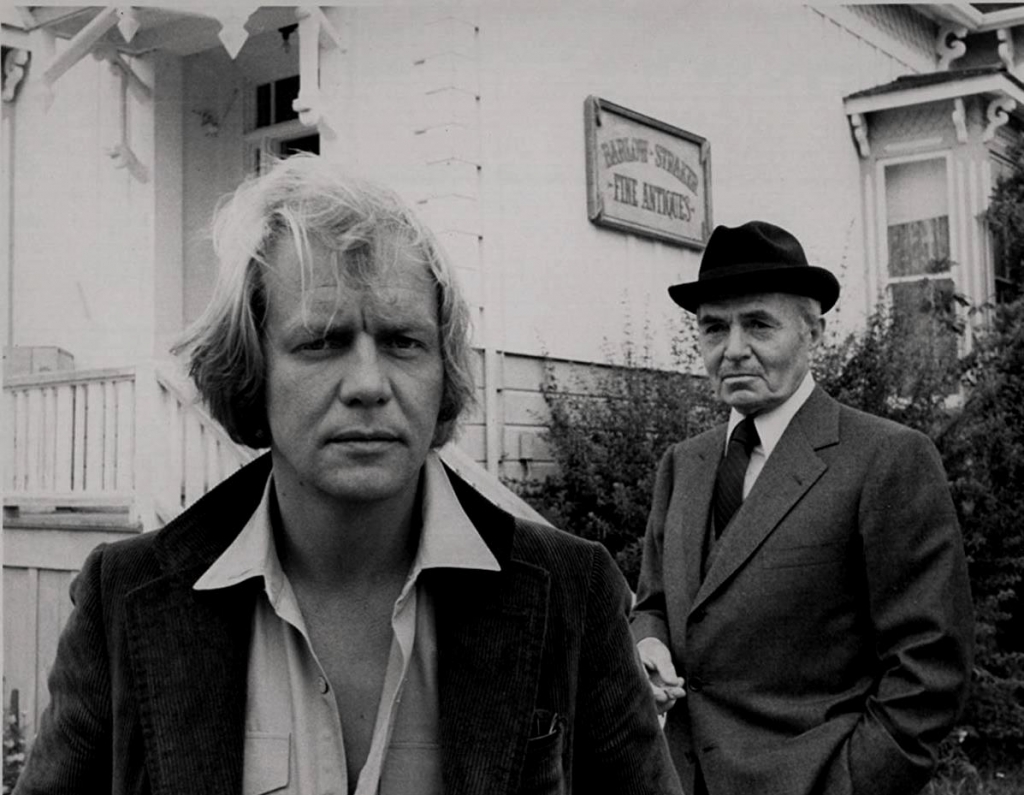

David Soul plays Ben Mears, King’s first troubled writer to make the screen transition.

He wears corduroy blazers with uncommon valor and his hair is never less than feathered, but there’s doom in those Coke-glass green eyes. The script doesn’t always look out for him — his rushed romance with the admittedly beguiling Bonnie Bedelia never quite clicks — but Soul came to play. His panicked cries, first for a witness, then a savior, as a dead body sits up in the morgue, interrupting his construction of a tongue depressor crucifix, should be curriculum for aspiring scream kings.

One of the major changes from the source material — abandoning any direct connection between the now-monstrous Mr. Barlow and ‘Salem’s Lot — is left to the star to sell in a monologue. To his credit and his alone, it works. Bad places attract bad people. Enough said.

But there sure is a lot more saying in Salem’s Lot.

The v-word isn’t used until the 130-minute mark.

The head v-word arrives in startling style around the same time.

Until then, it’s a lot of small-town charm and surveillance.

Who’s moving in to the old Marsten house? Did you see the doctor’s daughter making out with that drifter? How can an antique store even make money in a place like this? There’s an entire subplot about a truck-driving drunk trying to catch his wife cheating and, once he does, beating her. It’s a microcosmic inclusion of King’s Our Town sprawl and a welcome dose of Fred Willard as sex-object, but only serves to set up an early death. Charming, sure, but when you’ve got James Mason rubbing noses in his villainy like a Cambridge-educated Snidely Whiplash, there’s enough charm without the detours.

King originally intended the v-words to show up earlier because fans of his short stories would’ve seen them coming, but his editor told him to play coy for the sake of new readers. This is ultimately why the juiciest bits of Salem’s Lot are saved for the back nine.

Now that anyone invested enough in horror to have a Shudder subscription knows what’s coming, the first 90 minutes can’t help but creep. However, time has been kind on accident.

The sedative effect of ‘70s TV standards is now a long-game trap. Fall for it at your own peril. Acclimate to the soap-operatic rhythm and the eventual scares will only drive you that much deeper into the couch.

The reason Salem’s Lot still has a reputation is because it’s an absolute minefield.

One of the biggest jolts comes in broad daylight and doesn’t even involve the undead. Mr. Barlow makes his debut without warning in extreme, screeching close-up. Then there are the nightly knocks.

They seem tailormade to ruin the children still watching CBS on those fateful Saturday nights. A boy in bed hears a rap across the room. His missing friend floats outside his window in an impossible fog, eyes shining like pinballs. All he wants is to come in.

It’s agonizing, the kind of imagery distilled straight from bad dreams. The inevitable bite is shot backwards in a trick that plays more odd than eerie, but the timing still works like a hot knife through gray matter. Long before the interior of the Marsten house calls to mind the old Sawyer place, not so much distressed as it is digested, the signature is plain to see — this is a Tobe Hooper movie, emphasis mine.

Like its source material, Salem’s Lot suffers from what soon stripped it for parts. The ending sets up a potential weekly series which, independent of King’s disapproval, never happened. He attempted or at least intended to attempt a follow-up himself, but worked the idea into his later Dark Tower novels instead.

Hooper parlayed the blockbuster ratings into his first studio feature, The Funhouse. Despite the shameless advertising, it adheres closer to the Salem playbook than Chain Saw. That film, in turn, scored him the gig directing Poltergeist. In a just world, it would be considered another Tobe Hooper movie, but people love their conspiracies. If you ever heard someone claiming Steven Spielberg directed Poltergeist, you don’t need to say a word in protest or debate.

Just send them to the Lot. Especially if they’ve never visited before, that should scare them straight.

Follow Us!