Difficult to describe and hard to forget, “The Car” might have been a recipe for disaster; but something in this concoction is strangely satisfying.

There’s something wrong with The Car. Not the titular Lincoln from hell. There’s also something wrong with that, but if there wasn’t, none of us would be here. No, I mean the movie.

First time I saw it, I assumed the problem was with me. You can only enjoy a movie so much when watched between the text message vibrations of someone breaking up with you. But now, years removed from emotional trauma and basic cable, I watched it again on Shudder and can confirm: The Car still tastes funny. But at least now I know what I’m eating.

Now that Amblin is no longer just Steven Spielberg’s production company but an entire nostalgic subgenre of kids on bikes getting scared, it’s a treat to see something so beholden to his earlier, meaner works.

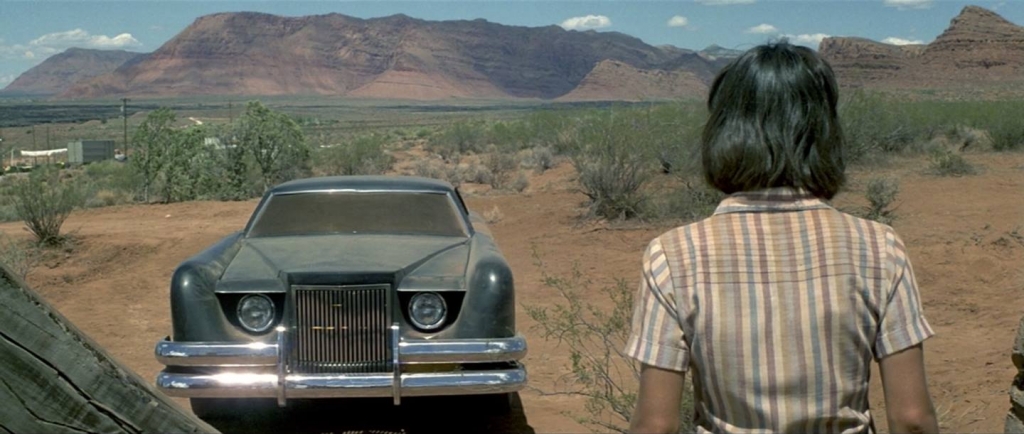

The Car is a clean 50-50 split between Duel and Jaws, with some later-period broken home melodrama for seasoning. Take the truck of the former, shrink the chassis and do it up like a toy coupe that comes packaged with a Bruce Wayne action figure, give it the omnipresent menace of the latter’s great white, then sic it on a beleaguered small-town and determined cop in head-to-toe khaki.

It’s easy enough to compare the IMDb tags, especially considering the aforementioned Amblinites, but to The Car’s credit, it has a feel for the intangibles, too.

The dusty anamorphic isolation of the American Southwest, courtesy of cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld, who shot Young Frankenstein three years prior and knew a thing or two about imitation, lends a one-road town in Utah the same deceptive tension as a one-weekend vacation island in Martha’s Vineyard. Everything’s quiet but the middle school marching band. The sky stays the same Technicolor shade of blushing-blue you don’t see in movies anymore.

There’s a postcard in any direction, if only they felt that welcoming. Instead, the desert is open water. No warning fin, but a distant dust cloud gaining fast. The Car comes riding out of the horizon like a four-cylindered horseman of the apocalypse.

No time for close-ups on awed faces caught in the headlights. Only blink-and-you’ll-miss-it bloodless carnage and the occasional absurdist glimpse of the black beauty struggling to lurk through the rocky terrain. The movie’s single most effective dose of dread comes from a locked-down long take of a phone conversation. As someone calls for help in the safety of their living room, out the window, framed by two floral print crimes against curtains, sit two little stars in the dark. They grow, flare, wink pink at the lens as they get closer. As they get louder, too.

I won’t give away the rewarding jolt, but it’s evidence of a knowing hand at the wheel.

Director Elliot Silverstein, also responsible for Cat Ballou, the American Film Institute’s 10th Greatest Western of All Time, had little passion for a project the producers referred to as “Jaws on land.”

Unlike many hired-gun filmmakers who end up playing with things that go bump in the night, though, Silverstein isn’t ashamed of The Car. He sat down for recent interviews about it for an unlikely Blu-Ray remaster and seemed politely surprised that his “Jaws on land” earned one. At the time, screenwriters Michael Butler and Dennis Shryack assumed their script would get gobbled up by the Corman factory, shot in a week, and jettisoned to the drive-in crowd before the check cleared.

They knew it was a glorified B and, if not an out-right rip-off, certainly a dedicated homage while the iron was still hot. This accidental recipe — a copycat script aimed at grindhouses, a big studio looking to capitalize on its own biggest hit, and a talented director who just wanted to work — gives THE CAR its strange flavor. Somehow, it plays alternatively as both a knowing and unintentional parody of the early Spielberg thrillers it so shamelessly apes.

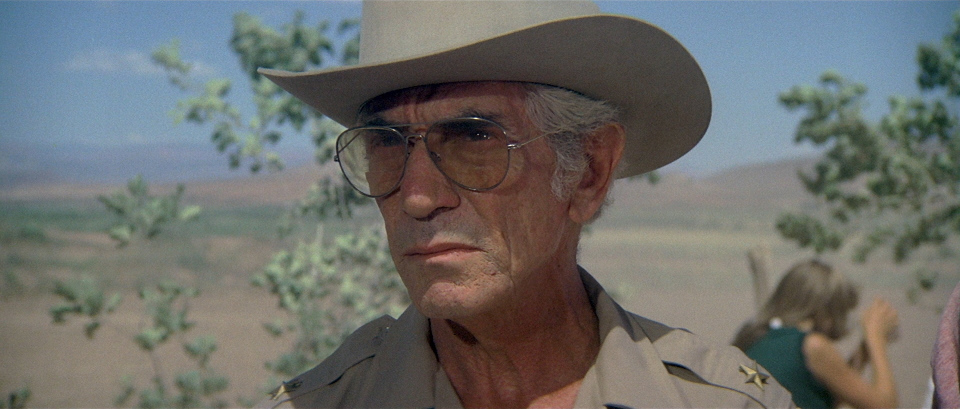

Life in sleepy Santa Yves looks a lot like life in Amity, only drier. But the townsfolk aren’t Rockwell-ready personalities so much as borderline vulgarities. There’s the cranky old man who beats his wife, and the sheriff who still has the hopeless, high school hots for her. Boys will be boys, including the one that’s been drawing naked pictures of his teacher. The principal seems angrier at the subject than the student. Deputies are given one character trait each so we keep straight who got run over and who’s still waiting to die.

Even our square-jawed, powerfully mustached hero, played by James Brolin when he could out-Burt Reynolds Burt Reynolds, feels like a ninety-minute wink. Why’s he the hero? Look at him. Does he have flaws? A divorce him and his kids get over within three scenes, but it sounds amicable anyway.

And while someone like Chief Brody can ask, “Do you think it was the same shark?,” and sound intelligently justified in doing so, the effect is a little different when the killer in question is a one-of-a-kind, immediately recognizable car that’s provided the only vehicular deaths in this town since its founding. Still, the good guys go, “You don’t think it was the same car, do ya?”

But is it a joke? The best and worst way I could describe The Car is a soap opera that’s occasionally interrupted by Christine.

When an irritable old man storms out of his house to find out who woke him up with a horn solo, he spots a hippie holding the only musical instrument for at least ten miles and still asks with a righteous fury, “That was you that woke me up with that bugle?” Then the possessed Lincoln shows up and flattens the hippie.

The Car is never better than these jarring gear-shifts between attempted suspense and small-town drama they left on the stove too long. Most of the stunts remain impressive, but is anyone’s first instinct, when a car wills itself to flip sideways and bounce off two squad cars simultaneously, to quake in terror?

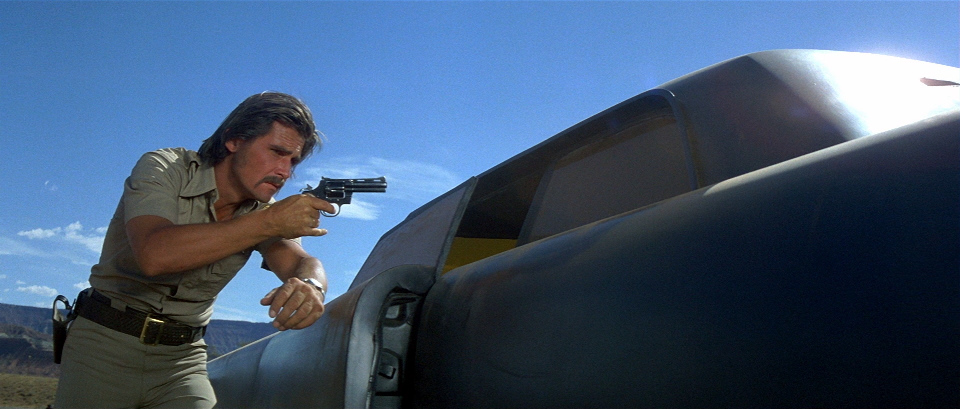

Later, in what may be the tensest scene in the movie, James Brolin finds himself locked in his garage with the fiberglass behemoth. It’s not running. Almost seems asleep. But can he open the door and escape without invoking its leaded fury? The conflict gets clever. There’s more than one way to die by General Motors in a poorly ventilated garage. But heaven forbid you wonder as I did: how did a sentient car get into his garage and lock the door behind it?

The Car dares you to watch every scene with the shaking head and squinted eye of a skeptic at a Vegas magic show.

How else can you even watch a haunted car Spielberg riff that opens with a quote from The Satanic Bible? I honestly forgot it did ten minutes after because, aside from Leonard Rosenman’s bombastic rendition of that Gregorian dirge you know from The Shining (“Dies Irae,” if you want it stuck in your head again) threatening a commercial break that never comes, there’s not much satanic about The Car.

It doesn’t like holy ground, but I know plenty of humans who also tend to steer clear. The sparing POV shots from the other side of the tinted windshield give nothing away — only a world stained the same yellow as shooting glasses, a color that turns everything into a target. But then there’s the end. Oh boy, the end.

I couldn’t tell how The Car was settling with me until the closing minutes.

The remaining deputies of Santa Yves devise a Wyle. E. Coyote-grade plan, and for this movie and jurisdiction, that’s more than enough to work. They push a bunch of rocks onto the car and it explodes. Then, in a display of special effects as unnervingly crude as they are crudely unnerving, something appears in the ensuing blaze. It must be seen to be believed, though probably not for the reasons anyone intended.

The assembled heroes watch in awe until it fades away with the wind. When an impossibly young Ronny Cox finds himself shaking at the sight, he implores the others, begging them to agree with what just happened: “I saw it in the fire!” But James Brolin cuts him off and declares the job done: “It’s over.” The devil drove into town, roadkilled half the population, and died under ten tons of rock in the Utah desert. And they all agree not to talk about it ever again. Cue the uplifting strings and end credits.

There’s the standard fakeout — the car’s distinctive taunting horn reminds us that it will return (and somehow did in a direct-to-DVD sequel this year). But the real damage is done. Something unexplainable and scarring happened to Santa Yves. Best to bury it forever and pretend it never happened. Wouldn’t want to interrupt the soap opera.

Now that’s one hell of an aftertaste.

Follow Us!