You may have seen “Skinamarink”, but have you truly experienced it the way it was meant to be experienced? A closer look may be warranted.

It’s unfortunate that I wanted to begin this article by finding a satisfactory definition for the word stupid. However, understanding this word’s definition, purpose, and use is part of my mission. The almighty Google defines it as “having or showing a great lack of intelligence and common sense.”

Based on the definition, it isn’t difficult to conclude that calling anything besides a person “stupid” is… well, stupid.

I was recently invited to be a guest on the Cheer and Loathing podcast, where we discussed the experimental horror films Skinamarink and Razzennest (trust me, we will all be talking about Razzennest a lot more in the near future). As I was articulating thoughts, new ones were forming in my noggin.

The Internet has opened a portal of uncontrollable chaos. It’s a doorway to both adventure and atrocity — and, in some ways, to an overall intellectual holocaust.

With this doorway, anyone with basic knowledge of a language can critique a movie. This can be a helpful tool to inform audiences about movies they may not have heard of and likely might not have discovered on their own. It’s also helped democratize film criticism and has brought to the forefront some very insightful and clever reviewers (Red Letter Media, Chris Stuckman, and Angry Joe, for example).

On the flip side, everyone throwing in their two cents has caused an overabundance of bad pennies, rendering the treasure chest of online film criticism nearly impossible to find any value in.

I don’t intend to belittle people who didn’t like Skinamarink; it’s not for everyone. I’m also not overly interested in refuting the weaknesses of the film, as there is some fair criticism that deserves a platform. I just wish there were more negative reviews that expanded on the consensus many seem to be coming to:

“It’s stupid. It’s boring. It’s pointless. Fuck this movie.”

It would be rather rude and presumptuous of me to attempt to teach people how to watch movies, especially impressionistic art films.

However, I believe if many viewers watched Skinamarink from a different frame of mind, they would find it to be an exceedingly enriching and valuable experience.

That’s not true for everyone, of course. It’s not a film that’s intended to be mass consumed, and it no doubt targets a niche audience. But I would argue it’s much more thoughtful, thought-provoking, and downright terrifying — on many levels — than most casual critics credit it for.

What surprises me most isn’t that a film like Skinamarink doesn’t resonate with everyone as much as it did with me. That’s expected and understandable. Instead, it’s the level of vitriol heaped on the film by those who seem enraged by their dislike of it.

Among the Skinamarink temper tantrums I have observed, one of the most common complaints is that it is boring. Nothing happens. And I’d argue that’s true on some level, depending on what lens you are watching it through.

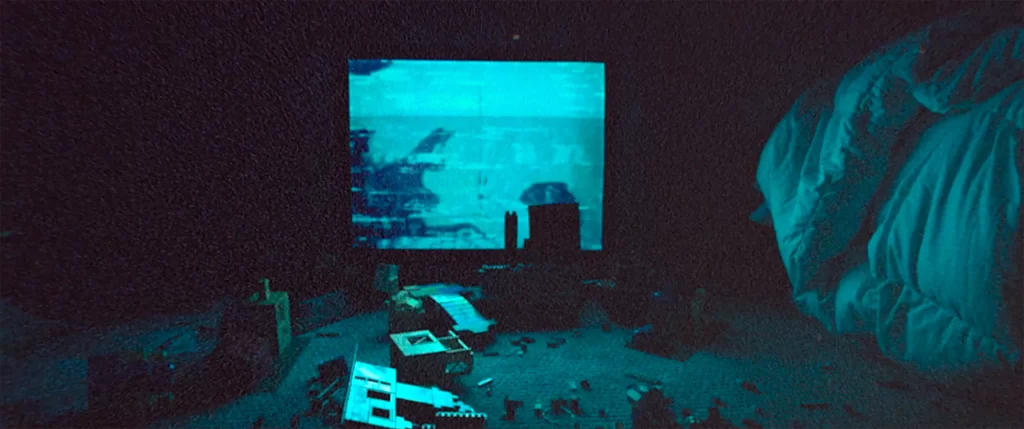

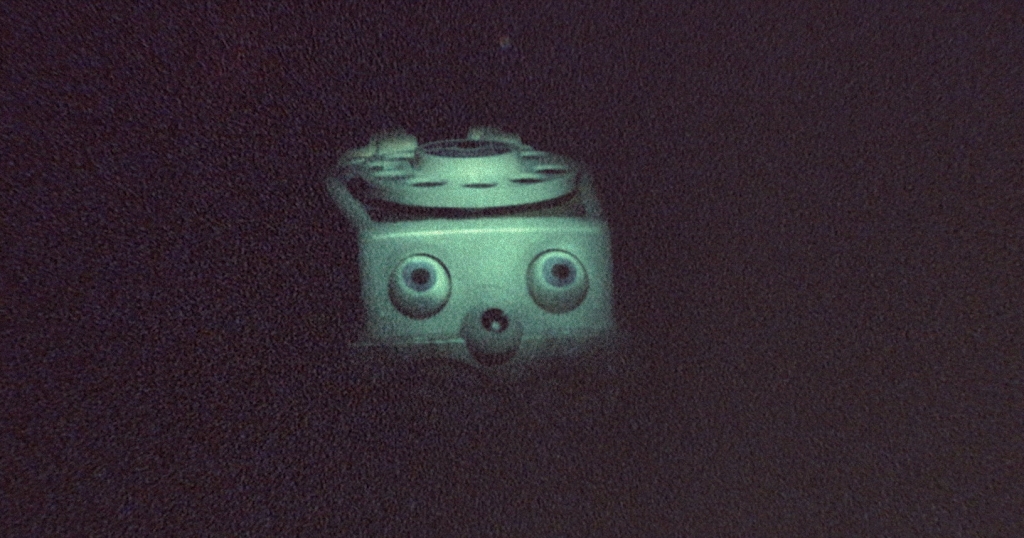

Personally, I was riveted by every long hallway shot, every seemingly innocuous child’s toy or vintage cartoon on a television set, every odd shot of a ceiling or windowless wall, every peak in a dark corner or backward glance.

It’s because this film is so unlike anything I’ve seen before that I found it impossible to predict where it was going or when the rug would be pulled out from under me. That made the experience of watching the film nerve-wrackingly tense.

Skinamarink removes the typical narrative structure and forces you to engage with the film on a visceral, emotional level.

Admittedly, it can be a challenge to consume because it doesn’t distract the senses with logic and a linear plot. It offers no signposts for direction, only hazy glimpses at someone in the distance you feel compelled to follow.

What you’re left with, instead, is a feeling… an experience.

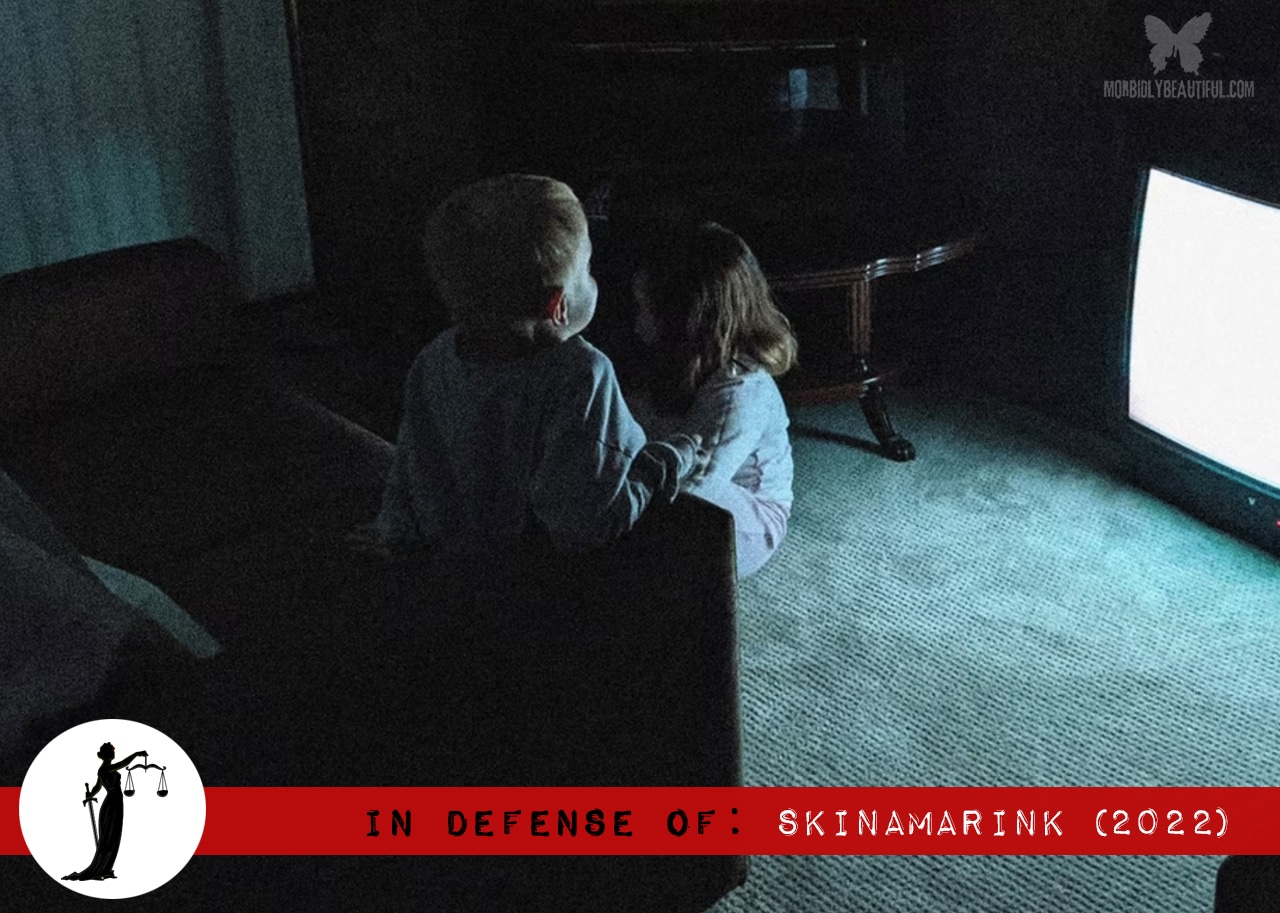

Skinamarink asks you to put yourself in the mind of a child who suddenly finds himself alone, disoriented, confused, and terrorized. As the viewer, you are asked to imagine what it would be like if the one place where you were supposed to be safe from all the horrors of the world became something you no longer recognized, and everything that made you feel protected was suddenly stripped away.

Our young protagonists in the film have no idea what is happening to them or why, and we, as viewers, don’t have any additional information to make heads or tails of the ensuing nightmare.

And that is precisely why it’s so utterly unnerving.

If you can allow yourself to occupy that headspace and be fully present for the entire harrowing experience, you may be surprised at how haunting and affecting it truly is.

If you can give it your undivided attention — free from distractions and unconstrained by expectations — Skinamarink may frighten you on a level few films come close to achieving. But it requires patience and the willingness to engage with the film differently.

At its most basic level, Skinamarink is a waking nightmare, portraying the fantastical fears of childhood and the horror of the unknown. It’s the very essence of fear itself and proves the old adage that the most frightening thing isn’t what we see or hear but what we can only imagine.

The film can absolutely be consumed and enjoyed on that level alone. However, if you choose to peel back the layers, there’s quite possibly a more palpable layer of very real trauma that gives the horror a more intense and devastating impact.

I encourage you to listen to the Cheer and Loathing episode I was on (right here or wherever you get your podcasts) for an in-depth discussion about some critical theories surrounding Skinamarink. If, for example, you read the film as an allegory for child abuse, I defy you not to be chilled to the bone while watching this film.

To bring this full circle, I will describe an encounter I had with someone throwing bad pennies at Skinamarink. I asked him, somewhat politely, why he thought it was stupid and a waste of time. I also suggested he be a little more open-minded and patient when watching movies. He replied that he shouldn’t have to be patient and open-minded and that it isn’t his job to do that.

He also said my comment was stupid.

Skinamarink proves there is hope for continued evolution and experimentation in the genre that keeps viewers — even those of us who think we’ve seen it all — interested and surprised.

Now, please tell me there is still hope for humankind as well.

Follow Us!